Broadwater Farm

| Broadwater Farm | |

|---|---|

|

| |

Broadwater Farm | |

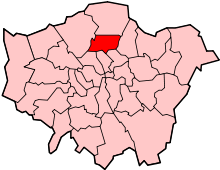

| Broadwater Farm shown within Greater London | |

| Population | 4,844 |

| OS grid reference | TQ3282590211 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | N17 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| EU Parliament | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Broadwater Farm, often referred to simply as "The Farm",[1][2] is an area in Tottenham, north London, straddling the River Moselle. The eastern half of the area is dominated by the Broadwater Farm Estate ("BWFE"), an experiment in high-density social housing built in the late 1960s. The western half of the area is taken up by Lordship Recreation Ground, one of north London's largest parks. Broadwater Farm in 2011 had a population of 4,844.[3]

The area acquired a reputation as one of the worst places to live in the United Kingdom following the publication of Alice Coleman's Utopia on Trial in 1985,[4] a perception made worse when serious rioting erupted later that year.[5] However, following a major redevelopment programme crime rates have dropped dramatically with a burglary rate of virtually zero percent.[6] It is also one of the most ethnically diverse locations in London; in 2005 its official population of 3,800 included residents of 39 different nationalities.[7]

Location

Broadwater Farm is situated in the valley of the Moselle, approximately six miles (10 km) north of the City of London. It is situated in a deep depression immediately south of Lordship Lane, between the twin junctions of Lordship Lane and The Roundway. It is immediately adjacent to Bruce Castle, approximately 547 yards (500 m) from the centre of Tottenham, and 1.2 miles (2 km) from Wood Green.[8]

History

Early history

Until the opening of the nearby Bruce Grove railway station on 22 July 1872[9] the area was still rural, although close in proximity to London and the growing suburb of Tottenham. Aside from a small group of buildings clustered around neighbouring Bruce Castle, the only buildings in the area were the farmhouse and outbuildings of Broadwater Farm, then still a working farm.[10]

Following the construction of the railways to Tottenham and Wood Green, development in the surrounding area took place rapidly. However, due to waterlogging and flooding caused by the River Moselle, Broadwater Farm was considered unsuitable for development and remained as farmland. By 1920, Broadwater Farm was the last remaining agricultural land on Lordship Lane, surrounded by housing on all sides.[10]

In 1932 Tottenham Urban District Council purchased Broadwater Farm. The western half was drained and converted for recreational use as Lordship Recreation Ground, while the eastern half was kept vacant for prospective development and used as allotments.[10] Heavy concrete dikes were built to reduce flooding of the Moselle in Lordship Recreation Ground, whilst on the eastern half of the farm the river was covered to run in culvert as far as Tottenham Cemetery.

The Broadwater Farm Estate

In 1967, construction of the Broadwater Farm Estate began on the site of the allotments, and an area of the south eastern part of the park was used to replace the allotments destroyed by the building of the estate. As initially built, the estate contained 1,063 flats, providing homes for 3,000–4,000 people.[11] The design of the estate was inspired by Le Corbusier,[6] and characterised by large concrete blocks and tall towers.[4]

Because of the high water table and the flood risk caused by the Moselle, which flows through the site, no housing was built at ground level.[12] Instead, the ground level was entirely occupied by car parks, and the buildings were linked by a system of interconnected walkways at first floor level known as the "deck level".[11] Shops and amenities were also located on the deck level.[13]

The 12 interconnected buildings were each named after a different World War II RAF aerodrome.[12] The most conspicuous buildings are the very tall Northolt and Kenley towers, and the large ziggurat shaped Tangmere block.

Deterioration

By 1973, problems with the estate were becoming apparent; the walkways of the deck level created dangerously isolated areas which became hotspots for crime and robbery, and provided easy escape routes for criminals.[6] The housing was poorly maintained, and suffered badly from water leakages, pest infestations and electrical faults.[12] More than half of the people offered accommodation in the estate refused it, and the majority of existing residents had applied to be re-housed elsewhere.[11] In 1976, less than ten years after the estate opened, the Department of the Environment concluded that the estate was of such poor quality that the only solution was demolition.[12] This decision was unwelcome to residents, and relations between the community and the local authority became increasingly confrontational.[12] A process of regeneration began in 1981, but it was hampered by a lack of funds and an increasingly negative public perception of the area.[11]

Utopia on Trial

By the time that Alice Coleman's critique of 1960s planned housing, Utopia on Trial, was published in 1985, the estate was regarded as being representative of unsuccessful large-scale housing projects. When a major exhibition by Le Corbusier in the mid-1980s proved unable to attract sponsorship, the refusal of sponsors to be associated with his name was attributed to the "Broadwater Farm factor".[4]

The book's criticism of alleged "lapses of civilised behaviour" on Le Corbusier inspired estates, claiming that residents of such buildings were far more likely to commit and to be victims of anti-social behaviour, were highly influential on the Thatcher government. Although the book focused on Tower Hamlets and Southwark and did not in fact cover Broadwater Farm, by the time of the book's publication the estate was becoming synonymous with this style of estate,[6] and the government began to put pressure on Haringey London Borough Council to improve the area.[4]

The Tenants' Association and the Youth Association

Although the demographics of Broadwater Farm at the time were roughly 50% black and 50% white, the Tenants' Association was all white and regarded with increasing distrust by black residents and white residents not connected with the Association. In 1981, residents set up the rival "Youth Association", which was widely applauded by many members of the local black community for challenging the perceived harassment by the controversial Special Patrol Group of local youths and of black residents of the estate. In 1983, the council gave the Tenants' Association an empty shop to use as an office and a vague authority to "deal with local problems", heightening antagonism between the Tenants' Association and Youth Association, which in turn set up its own youth club, advice centre, estate watchdog and local lobbying group.[12]

Early regeneration projects

Despite the lack of funds and unwillingness on the part of the council to commit to regeneration, by 1985 it appeared that progress was being made in solving the area's problems. Pressure from the Tenants' Association and the Youth Association forced the council to open a Neighbourhood Office. In 1983, a tenants' empowerment agency, Priority Estates Project, was appointed to coordinate residents' complaints and concerns, and residents were included on interview panels for council staff dealing with the area.[12]

A number of initiatives aimed at providing activities for disaffected local youths and at integrating the mixture of ethnic communities in the area appeared to be succeeding; Sir George Young, then Minister for Inner Cities, secured significant funding for improvements. Broadwater Farm began to be seen as a case study in regenerating a failed housing development.[12] Princess Diana paid a visit to the estate in February 1985, to commend the improvements being made,[1] but much of the apparent progress was superficial. The problems caused by the deck-level walkways had not been solved; children from Broadwater Farm were still under-achieving academically in comparison to the surrounding areas; the unemployment rate stood at 42%; and perhaps most significantly of all, given later events, the mutual distrust between the local residents—particularly those from the Afro-Caribbean community—and the predominantly White British and non-local police force had not been effectively addressed.

Broadwater Farm riot

There had been earlier riots in Brixton and in Handsworth in Birmingham,[14] which were indicative of a period of rising racial tension,[15] during which some police methods such as raids, saturation policing and stop and search tactics increased the frustration of some members of the black community.[16][17]

Floyd Jarrett, whose home was about a mile from the Farm, was arrested by police on 5 October 1985, having given false details when stopped with an allegedly false tax disc. While he was in custody, four officers attended his home to conduct a search. During the search, his mother Cynthia Jarrett collapsed and died.[13][18] It has never been satisfactorily concluded how and why Cynthia Jarrett died, and whether it was a heart attack or due to police actions.[19]

The next day, 6 October 1985, saw a small demonstration outside Tottenham police station, which initially passed off relatively peacefully other than a bottle being thrown through one of the station's windows.[18] At 3.15 pm two officers were attacked and seriously injured by the crowd,[13] suffering gunshot wounds.[18] Three journalists were also treated for gunshot wounds.[18]

Murder of PC Keith Blakelock

At 6.45 pm a police van answering a 999 call to Broadwater Farm was surrounded and attacked.[20] As further police officers made their way to the area, rioters erected barricades on the deck level and the emergency services withdrew from the deck level.[13] At 9.30 pm fire broke out in a newsagent on the deck level of the Tangmere block. Firefighters attempting to put out the fire came under attack, and police attended to assist them. As the situation escalated, police and firefighters withdrew. In the withdrawal, PCs Keith Blakelock and Richard Coombes became separated from other officers. A group of around 40 people[21] attacked them with sticks, knives and machetes, leading to PC Blakelock's death and serious injuries to PC Coombes.[22] As news of the death spread, the rioting subsided. Local council leader Bernie Grant claims to have been misquoted as saying that "What the police got was a bloody good hiding".[23]

Three local residents, Mark Braithwaite, Engin Raghip and Winston Silcott, were convicted of PC Blakelock's murder. However, three years later their convictions were overturned when it was discovered that police notes of their interviews had been tampered with.[24] The person or persons guilty of the murder have never been identified but in 2010, a man was arrested on suspicion of murdering PC Blakelock.[25]

Reconstruction

After the events of 1985, Broadwater Farm became the focus of an intensive £33 million regeneration programme in response to the problems highlighted by the riots.[26] The all-white Tenants Association was restructured more accurately to reflect the community, and residents' concerns seriously addressed by the authorities.[12] A local management team was brought in to oversee improvements to the estate and to collect rents and enforce regulations, instead of continuing to attempt to run the estate centrally from Haringey Council's central offices.[6] The deck level was dismantled and the overhead walkways demolished, with the shops and amenities relocated to a single ground-level strip of road to transform the semi-derelict Willan Road into a "High Street" for the area.[26] The surrounding areas were landscaped and each building redesigned to give it a unique identity.[7] A network of council-run CCTV cameras was installed to monitor the streets and car parks, and each building staffed by a concierge to deter unwanted visitors.[26] Two giant murals were painted which now dominate the area, one of a waterfall on the side of Debden block[6] and one depicting Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, John Lennon and Bob Marley on Rochford block.[7] Disused shops left empty following the withdrawal of businesses after the riots were converted into low-cost light industrial units to provide employment opportunities for residents and prevent capital from flowing out of the area.[27] Since the redevelopment, the flow of people leaving the estate has slowed to a trickle, and there is now a lengthy waiting list for housing.[28]

Crime rates

Since the regeneration, Broadwater Farm now has one of the lowest crime rates of any urban area in the world. In the first quarter of 2005, there were not any reported robberies or outdoor assaults on Broadwater Farm, and only a single burglary, from which all property was recovered and the suspect arrested; this compares with 875 burglaries, 50 robberies and 50 assaults in the third quarter of 1985, immediately preceding the riot.[7] In an independent 2003 survey of all the estate's residents, only 2% said they considered the area unsafe, the lowest figure for any area in London.[26] The estate also has the lowest rent arrears of any part of the borough.[6]

In 2005 the Metropolitan Police disbanded the Broadwater Farm Unit altogether as no longer required in an area with such a low crime rate.[7]

Places of interest

Bruce Castle, once the home of Rowland Hill, inventor of the postage stamp, is on the north side of Lordship Lane immediately opposite Broadwater Farm. It was built by William Compton in the 16th century, and has been a public museum since 1906.[29] It houses the public archives of Haringey Council, as well as a large display on the history of the postal system.[30]

Broadwater Farm is home to the Broadwater United football coaching programme. Set up in the aftermath of the events of 1985 with the intention of providing a focus for local youths, it has subsequently produced a number of professional footballers, including Jobi McAnuff, Lionel Morgan and Jude Stirling, son of the programme manager Clasford Stirling.[31]

Facilities

Schools

In 2007 a new Children's Centre opened on the estate, with nursery places for 104 children. It is considered one of the best designed nursery schools in the world, and won the Royal Institute of British Architects's Award for 2007.[32]

Broadwater Farm contains three primary schools, the general Broadwater Farm Primary School and the Moselle and William C Harvey schools for pupils with special needs. An ongoing programme is underway to integrate the three schools onto a single campus.[33] Secondary education is provided by nearby Woodside High School, formerly named White Hart Lane School, approximately 200m outside the Broadwater Farm area.

Shops

Following the riots, many shops in Broadwater Farm withdrew from the area, and those that remained closed following the demolition of the deck level. Broadwater Farm is consequently extremely poorly served by shops. Haringey Council has provided 21 small "enterprise units" at a deliberately low cost to entice firms to open in the area,[34] but these have proved hard to fill. However, Broadwater Farm is only 400m from the shops and supermarkets of Tottenham High Road, and approximately 2 km from the Shopping City supermall at Wood Green.

Transport

Due to the waterlogged ground and lack of population prior to the containment of the Moselle, Broadwater Farm was bypassed by the Underground. Bruce Grove railway station, 400m east of the estate, connects the area to central London. Because of the narrow streets, double-decker and bendy buses are unable to serve the area. From 11 February 2006 the W4 route, which utilises Alexander Dennis Enviro200 Dart to navigate the narrow streets and sharp bends, was diverted to run into the estate,[2][35] providing direct public transport links for the first time. A number of other bus routes run along Lordship Lane, immediately to the north and Philip Lane to the south. Turnpike Lane tube station is within walking distance to the south west.

Demographics

There are currently between 3800 and 4000 residents of Broadwater Farm. Following the events of 1985 a number of local residents left and were replaced mainly by recent immigrants, particularly Kurds, Somalis and Congolese.[5] In 2005, approximately 70% of residents were from an ethnic minority background[5] and 39 different languages were spoken on the estate.[7] In 2011, only 13.4% of residents were White British, 11.9% were Asian and 36.1% were Black.[36]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Broadwater Farm Estate. |

References

- 1 2 Barling, Kurt (30 September 2005). "20 Years On". BBC News. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- 1 2 "Broadwater Farm celebrates return of W4 bus service". London Borough of Haringey. 3 March 2006. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- ↑ 14 Output areas within the West Green ward make up Broadwater Farm and all have a N17 Postcode http://ukcensusdata.com/west-green-05000282#sthash.W4nK4B0.xrMyJkWE.dpbs

- 1 2 3 4 "Broadwater Farm Revisited". London Bulletin. November 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- 1 2 3 Wolmar, Christian (15 September 2005). "Broadwater Revisited". Evening Standard.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wolmar, Christian (January 2005). "20 Years Later at Broadwater Farm". Housing Today.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Trivedi, Chirag (6 October 2005). "Transforming Broadwater Farm". BBC News. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ London A-Z. Sevenoaks: Geographers' A-Z Map Company Ltd. 2002. ISBN 1-84348-020-4.

- ↑ Connor, Jim (2004). Branch Lines to Enfield Town and Palace Gates. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-904474-32-2.

- 1 2 3 "Tottenham Growth after 1850". A History of the County of Middlesex. Victoria County History. 5: 317–324. 1976. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 "History of Broadwater Farm". London Borough of Haringey. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Antwi, Peter. "Broadwater Farm Estate: The Active Community" (PDF). Housing Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 "Broadwater Farm Riot 1985". Metropolitan Police Service. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ Paul Harris (2011). "PC Keith Blakelock murder: Will his killers finally face justice? | Mail Online". dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Mark Hughes (10 February 2010). "Man held over PC Blakelock murder - Crime, UK - The Independent". The Independent. London: INM. ISSN 0951-9467. OCLC 185201487. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Vince Dicey (2007). "A chronology of injustice, Issue 36". socialismtoday.org. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Michael McConville, Dan Shepherd (1992). Watching police, watching communities. Routledge. p. 238. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Parry, Gareth; Ezard, John (7 October 1985). "Policeman Killed in Riot". The Guardian.

- ↑ Barkham, Peter (9 March 2007). "When the Police Got it Wrong". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Policeman Killed in Tottenham Riots". BBC News. 6 October 1985. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ↑ "This Day in History". The History Channel. Archived from the original on 30 April 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ "Black History: What Happened in 1985". BBC. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ "Bernie Grant, Militant Parliamentarian". Chronicle World. 15 January 2001. Archived from the original on 6 April 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ "Silcott Not Guilty of PC's Murder". BBC News. 25 November 1991. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ Cowan, Rosie; Dodd, Vikram (4 December 2004). "Police Reopen Blakelock Murder Inquiry". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 "Broadwater Farm: Services and Facilities". London Borough of Haringey. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ "Broadwater Farm". Hidden London. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ↑ Rayner, Jay (19 October 2003). "In the Shadow of the Past". The Observer.

- ↑ "Bruce Castle Museum". London Borough of Haringey. 5 June 2007. Archived from the original on 24 April 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "Bruce Castle Museum". The Art Fund. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ↑ Edwards, Richard (10 October 2005). "From Tragedy to Talent Flow". The Times. London.

- ↑ "Broadwater Farm Children's Centre". Royal Institute of British Architects. 17 May 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ↑ "Broadwater Farm: Education". London Borough of Haringey. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ "Broadwater Farm: Enterprise Centres". London Borough of Haringey. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ↑ "W4". London Bus Routes. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ↑ Services, Good Stuff IT. "West Green - UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 4 September 2015.