49th (West Riding) Infantry Division

| West Riding Division 49th (West Riding) Division 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division 49th (West Riding) Armoured Division 49th (West Riding and Midland) Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

|

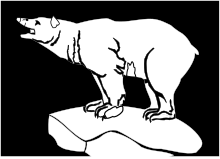

Division badge, third pattern, replaced the second pattern during the Second World War in 1943. | |

| Active |

1908–1919 1920–1945 1947–1967 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type |

Infantry Armoured |

| Size | Division |

| Nickname(s) |

"Barker's Bears" "The Polar Bears" "The Polar Bear Butchers" |

| Engagements |

First World War Second World War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Sir Evelyn Barker Sir Gordon MacMillan |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |

_Division_insignia.png) Shoulder sleeve insignia sign, used on signboards during the First World War. |

| Identification symbol |

Badge worn at the top of the sleeve between the wars and early in the Second World War, made of white metal.[1] |

| Identification symbol |

Badge, second pattern, adopted in Iceland during the Second World War.[1] [lower-alpha 1] |

The 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army. The division fought in the First World War in the trenches of the Western Front, in the fields of France and Flanders. During the Second World War the division fought in the Norwegian Campaign and in North-western Europe. After the Second World War it was disbanded in 1946, then reformed in 1947. It remained with Northern Command until finally disbanded in 1967.

Formation

The division was first created on 1 April 1908 upon the creation of the Territorial Force (TF), the British Army's part-time reserve. Originally designated the West Riding Division, the division was composed of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd West Riding Brigades, each with four infantry battalions, along with supporting units. The division was one of fourteen divisions that made up part of the peacetime TF.[3]

First World War

Elements of the division had, by the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, just departed for their annual summer camp and were mobilised for war service on 5 August, the day after Britain entered the war. According to the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907, men of the TF were not obligated to serve overseas without their permission and so, on 31 August, the division was ordered to form a second-line reserve unit, the 2nd West Riding Division, formed mainly from those men who, for various reasons, choose not to volunteer for overseas service.[3] The division, under the command of Major General Thomas Baldock, who had been in command since 1911, moved to the South Yorkshire/Lincolnshire area for concentration and spent the next few months engaged in training.[3]

By late March 1915 training had progressed to the point where the division was warned for a potential move overseas. By mid-April the division was in France, and was to remain on the Western Front as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) for the rest of the war.[3] Soon after arrival the division, although unfamiliar with trench warfare, was assigned to Lieutenant General Sir Henry Rawlinson's IV Corps of the BEF, and played a relatively minor role in the Battle of Aubers Ridge, where Major General Baldock, the divisional commander, was wounded in action. The division was redesignated the 49th (West Riding) Division on 15 May 1915 and given the White Rose of York as its insignia.[3] The division's three brigades were also redesignated, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd West Riding Brigades becoming the 146th (1st West Riding), 147th (2nd West Riding) and 148th (3rd West Riding) Brigades, respectively.[3] After Aubers Ridge the division, now commanded by Major General Edward Perceval, was not engaged in any major battles until 19 December 1915, when the division, now part of Lieutenant General John Keir's VI Corps, participated in the first Phosgene attack but suffered comparatively few losses.[3]

The first few months of 1916 were not spent in any major actions and the division held a relatively quiet sector of the Western Front. As part of Lieutenant General Thomas Morland's X Corps, the division fought in the Battle of the Somme, fighting in the Battle of Albert, followed by the Battle of Bazentin Ridge.[3] Transferring to Lieutenant General Charles Fergusson's II Corps, the division then took part in the Battle of Pozières.[3] Rested throughout August, the division then fought in the Battle of Flers–Courcelette and the Battle of Thiepval Ridge.[3]

Again moved to a more quiet sector of the front, the division spent, as it had in 1916, the first few months of 1917 uneventfully in the Ypres Salient, not being employed in any major offensives until the division was to take part in Operation Hush.[3] However, the division was not employed in the operation and instead fought in the final stages of the Passchendaele offensive, in the Battle of Poelcappelle.[3]

In early 1918 the division, now commanded by Major General Neville Cameron, was again holding a quiet sector of the Western Front.[3] Throughout January and February, due to a severe shortage of manpower in the BEF, many of the division's infantry battalions were either disbanded, merged with other understrength units or posted elsewhere. The manpower shortage compelled the reduction of each of the division's three infantry brigades from four to three battalions.[3] In the latter half of 1918 the division, mostly unaffected by the German Army's Spring Offensives, fought in all the major battles of the Lys offensive, and in the Hundred Days Offensive, which saw the war turn in favour of the Allied powers, come to an end on 11 November 1918.[3]

Order of battle

The 49th Division was constituted as follows during the war:[3]

- 1/5th Battalion, Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire Regiment)

- 1/6th Battalion, Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire Regiment)

- 1/7th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion, Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire Regiment)

- 1/8th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion, Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire Regiment) (until January 1918)

- 146th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (from 27 January 1916, moved to 49th Battalion, Machine Gun Corps 1 March 1918)

- 146th Trench Mortar Battery (from 12 June 1916)

- 1/4th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment)

- 1/5th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment) (until January 1918)

- 1/6th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment)

- 1/7th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment)

- 147th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (from 26 January 1916, moved to 49th Battalion, Machine Gun Corps 1 March 1918)

- 147th Trench Mortar Battery (from 12 June 1916)

- 1/4th Battalion, King's Own (Yorkshire Light Infantry)

- 1/5th Battalion, King's Own (Yorkshire Light Infantry) (until February 1918)

- 1/4th (Hallamshire) Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

- 1/5th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

- 148th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (from 6 February 1916, moved to 49th Battalion, Machine Gun Corps 1 March 1918)

- 148th Trench Mortar Battery (from 12 June 1916)

- Divisional Troops

- 1/3rd Battalion, Monmouthshire Regiment (joined as pioneer battalion April 1915, left August 1916)

- 19th (Service) Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers (3rd Salford Pals) (joined as pioneer battalion August 1916)

- 199th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (joined 19 December 1916, left 29 October 1917)

- 254th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (joined 26 November 1917, moved to 49th Battalion, Machine Gun Corps 1 March 1918)

- 49th Battalion Machine Gun Corps (formed 1 March 1918)

- Divisional Mounted Troops

- C Squadron, 1/1st Yorkshire Hussars (left 8 May 1916)

- F Squadron, North Irish Horse (briefly between April and June 1916)

- West Riding Divisional Cyclist Company, Army Cyclist Corps (left 26 May 1916)

- Divisional Artillery

- CCXLV (I West Riding) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

- CCXLVI (II West Riding) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

- CCXLVII (III West Riding) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery (broken up 28 February 1917)

- CCXLVIII (IV West Riding) (Howitzer) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery (broken up 18 October 1916)

- West Riding Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery (a battery of four 4.7-inch guns which left the division to join VIII Brigade, II Group HA on 24 April 1915; returned to division 13 May 1915, and finally left on 28 June 1915, rejoining VIII Brigade)

- 49th Divisional Ammunition Column, Royal Field Artillery

W.49, V.49 Heavy Trench Mortar Battery, Royal Field Artillery (formed by 17 May 1916; V absorbed W by 7 June 1917; left for X Corps on 7 February 1918)

- X.49, Y.49 and Z.49 Medium Mortar Batteries, Royal Field Artillery (formed by 4 April 1916 from former 34, 37 and 48 TMB’s; by 9 February 1918, Z broken up and batteries reorganised to have six 6-inch weapons each)

- Royal Engineers

- 1st West Riding Field Company, Royal Engineers (left 6 February 1915, later retitled 455th)

- 456th (2nd West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers

- 458th (2/1st West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers (joined June 1915)

- 57th Field Company, Royal Engineers (joined July 1915)

- 49th Divisional Signals Company, Royal Engineers

- Royal Army Medical Corps

- 1st West Riding Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps

- 2nd West Riding Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps

- 3rd West Riding Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps

- 49th Sanitary Section, Royal Army Medical Corps (left 2 April 1917)

- Other Divisional Troops

- 49th Divisional Train, Army Service Corps (retitled from the West Riding Divisional Transport and Supply Column, and the units also retitled as 463, 464, 465 and 466 Companies, Army Service Corps)

- 1st West Riding Mobile Veterinary Section, Army Veterinary Corps

- 49th Divisional Ambulance Workshop (absorbed into Divisional Supply Column 4 April 1916)

243rd Divisional Employment Company (joined 16 June 1917)

Between the wars

The division was disbanded after the war but was reformed, now as the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division, when the old TF was itself reconstituted as the Territorial Army (TA) in 1920, with the same composition as pre-1914.[3] The division was stationed in Northern Command. During the interwar period, particularly in the late 1930s, many of the division's units were converted into other roles, mostly into artillery, searchlight or armoured regiments so that, by the time war broke out in September 1939, the division's composition, which included units from the disbanded 46th (North Midland) Division, was much changed from what it was in 1914. Of note, Bernard Montgomery, who was later to have association with the 49th Division, served with this division in 1923, when he was a General Staff Officer Grade 2 (GSO2). Upon the doubling of the size of the TA in mid-1939 the division, as it had in the First World War, raised a second-line duplicate formation, the 46th Infantry Division, when another European conflict, most likely with Nazi Germany, was becoming increasingly inevitable.

Second World War

Mobilisation and early months

Shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War on 3 September 1939, the division, under Major General Pierse Mackesy,[4] was mobilised for full-time war service and, with conscription having been introduced in the United Kingdom some months earlier, and with many units understrength after having to post officers and men to the second-line units, the division absorbed many conscripts.[5] Although war was declared, the division, serving under Northern Command,[6] still with the 146th, 147th and 148th Infantry Brigades under command, was initially engaged in static defensive duties, guarding vital points and little time was allotted for training. However, training began soon afterwards with the overall intention being that the division, once fully trained, would join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France. In the event, this was not to happen as, in February 1940, the division received orders to form part of "Avonforce" and be sent to Finland, via Norway, and aid the Finnish Army during its Winter War with the Soviet Union.[5] On 12 March, however, the Finnish, severely outnumbered by the Russians, surrendered, thus cancelling the order.[5][7]

On 4 April, the 49th Division ceased to function and the 146th and 148th Brigades (with the 147th Brigade remaining in England), both very poorly trained and equipped, took part in the short and ill-fated Norwegian Campaign, that were intended to retake the ports of Trondheim and Narvik from the German Army.[5] The 146th Brigade came under command of "Mauriceforce", with the 148th under "Sickleforce".[5] The campaign, poorly planned, was a complete disaster and the two brigades, fighting as two different brigade groups, and widely scattered from each other, withdrew from Norway in May 1940.[8] One consolation, however, was that they gained the distinction of being amongst the very first British troops to fight the enemy in the Second World War, and certainly the first Territorials to do so. The brigades returned to the United Kingdom, where, on 10 June, the division was reconstituted in Scottish Command[6] under Major General Henry Curtis.[4][9] Curtis, the new General Officer Commanding (GOC), had commanded the division's sister formation, the 46th Division, during the Battle of France and in the BEF's subsequent retreat to Dunkirk, where it was evacuated to England, albeit with very heavy casualties.[5] The 148th Brigade, which had suffered well over 1,400 casualties in Norway, did not rejoin the division, later becoming an independent formation.[10]

Service in Iceland, 1940−42

The division, now with only the 146th and 147th Infantry Brigades, left and departed for Iceland, the 146th arriving there on 8 May,[11] the 147th on 17 May,[12] and the divisional HQ arriving on 23 June, where it was redesignated HQ Alabaster Force and, in January 1941, Iceland Force before finally being redesignated HQ British Troops Iceland.[5] Both brigades were thereafter stationed in Iceland until 1942.[13] As a result, a new divisional insignia, featuring a polar bear standing on an ice floe, was adopted.[5] Also stationed there from late October 1940 was the 70th Independent Infantry Brigade.[14] In 1941, at the request of British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, the division was trained in mountain warfare and also in arctic warfare.[15] By April 1942 responsibility for Iceland had been handed over to the United States, with the arrival in July the previous year of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade and the three brigades began to be relieved, and Major General Curtis suggested the Marines wear the polar bear insignia.[5][15] A junior officer of the 1st Tyneside Scottish wrote of the experience in Iceland: "Iceland had given us so much. More than anything it had forged a firm and abiding link between all who wore the Polar Bear".[15]

Reconstitution and training for Overlord

On 26 April 1942, the division HQ was again reconstituted, this time in South Wales, serving under Western Command, commanded by Major General Curtis.[4] The division initially had only the 147th Brigade under command, although the 70th Brigade became part of the division on 18 May, followed on 26 August by the 146th Brigade, and numerous other supporting units which later joined the division.[16][5] The division then spent the next few months engaged in training throughout Wales and England, with the intention of catching up with the latest training methods. In March 1943 the division, abandoning the mountain and arctic warfare roles, participated in Exercise Spartan, the largest military exercise held in England.[17] In April 1943 the division was assigned to I Corps, under Lieutenant General Gerard Bucknall, and was earmarked as an assault division for the invasion of Normandy, scheduled for spring the following year. On 30 April the division received a new GOC, Major General Evelyn "Bubbles" Barker.[4] A highly competent officer and a decorated veteran of the First World War, Major General Barker ordered the divisional sign to be changed from its current emblem of a polar bear with its head lowered, which the GOC believed to be a sign of a lack of martial intent, into a more "aggressive" sign.[18] "That Bear is too submissive. I want a defiant sign for my division, lift up its head and make it roar", Barker wrote. Subsequently the 49th Division was issued with a new "aggressive" insignia, now featuring a Polar Bear with its head facing upwards, roaring.[18][5]

In July, as the division was selected to be one of the three divisions selected to spearhead the Normandy invasion, the 49th was sent to Scotland, where it began strenuous training in amphibious warfare and combined operations.[19] However, in late 1943, when General Sir Bernard Montgomery took over command of the 21st Army Group, which commanded all Allied land forces in the upcoming invasion, the veteran 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division was chosen by Montgomery as one of the two British assault divisions – the other being the 3rd Division – and the 49th Division, despite training for the role for many months, was instead relegated to a backup role.[20] In January 1944 the division moved to East Anglia where on 2 February it transferred from Lieutenant General John Crocker's I Corps to XXX Corps,[6] under Lieutenant General Gerard Bucknall, and continued training for the invasion.[21]

Northwestern Europe, 1944−45

On 13 June 1944, most of the 49th Division, after just over two years of training, landed in Normandy as part of Operation Overlord.[6] The division arrived too late to take part in the Battle of Villers-Bocage, where the veteran 7th Armoured Division suffered a serious setback, but were involved in the numerous attempts to capture the city of Caen. The division, after landing, was only involved in relatively small-scale skirmishes, most notably on 16 June around Tilly-sur-Seulles, where the 6th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's Regiment, of the 147th Brigade, suffered some 230 casualties − 30% of its war establishment strength − in a two-day battle whilst attempting to capture Le Parc de Boislande.[22] The position was eventually taken by the 7th Battalion, Dukes.[23] The 49th's first major action as a division came during Operation Martlet, the first phase of Operation Epsom, the British attempt to capture Caen. Although Lieutenant General Richard O'Connor's VIII Corps made the main effort, XXX Corps, with the 49th Division under control, was to protect VIII Corps right flank by seizing the Rauray ridge.[24]

The operation commenced on 25 June, and the division, supported by elements of the 8th Armoured Brigade and a massive artillery barrage from over 250 guns, initially went well, with the first phase objective, the town of Fontenay, being captured by the end of the first day against units of two German panzer divisions (the 2nd and 9th).[25] However, capturing Rauray itself proved more difficult although, after hard fighting, much of it in close quarters, it eventually fell to the 70th Brigade on 27 June which, for the next few days, had to ensure a series of very fierce counterattacks, with the 1st Battalion, Tyneside Scottish bearing the brunt of the German attacks, which were repulsed with heavy losses on both sides, although the Germans suffering by far the greater.[26] It was during this period of the fierce fighting in Normandy that the Nazi propaganda broadcaster, Lord Haw-Haw, referred to the division as "the Polar Bear Butchers", apparently due to British soldiers wearing a Polar Bear flash who had massacred SS tank crew who were surrendering but were instead mowed down.[27] The 49th's GOC, Major General "Bubbles" Barker, explained it in his diary on 2 July, "Yesterday the old 49 Div made a great name for itself and we are all feeling very pleased with ourselves. After being attacked on my left half, all day by infantry and tanks, we were in our original positions after a small scale counter attack by the evening. We gave him a real bloody nose and we calculate having knocked out some 35 tanks mostly Panthers. One of my Scots Battns distinguished themselves particularly. We gave him a proper knockout with our artillery with very strong concentration on any point where movement was expected".[27]

The division, by now known widely as, "Barker's Bears", then held the line for the next few weeks, absorbing reinforcements and carrying out patrols[28] until its participation in the Second Battle of the Odon, before, on 25 July, transferring from Bucknall's XXX Corps, in which the division had served nearly six months, to Lieutenant General John Crocker's I Corps.[6] The corps was now part of the First Canadian Army and the 49th Division, on the corps' left flank, in August, took part in the advance towards the Falaise Pocket, where the Germans were attempting to retreat to, capturing thousands of Germans in the process.[29] It was during this time that the division lost the 70th Brigade, which was broken up to provide reinforcements to other units.[30] However, substituting the 70th Brigade was the 56th Brigade, formerly an independent formation comprising entirely Regular Army units which had landed in Normandy on D-Day.[31]

The division reached the River Seine in the late August, and, upon crossing the river, turned towards the capture of Le Havre, which was captured on 12 September (see Operation Astonia) with very light casualties to the 49th Division and its supporting units − 19 killed and 282 wounded − and capturing over 6,000 Germans in the process.[32] Major General "Bubbles" Barker, the GOC, wrote in his diary that it "will be a memorable day for the Div[ision] and myself".[33] However, the division then had all its transport sent forward to other units then advancing into Belgium, temporarily grounding the "Polar Bears", although giving the division a few days rest, deservedly so after having endured almost three months of action since landing in Normandy and suffered over 5,000 casualties.[34]

The division received the order to move, arriving, after travelling some 200 miles, in southern Holland at a concentration area on 21 September, ten miles south of the Antwerp-Turnhout Canal. Over the next few days the division liberated Turnhout and crossed the Antwerp-Turnhout Canal.[35] It was during this period that the division was awarded its first and only Victoria Cross (VC) of the Second World War, belonging to Corporal John Harper of the Hallamshire Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment.[36] The division, after being on the offensive since landing in Normandy, then spent the next few weeks on the defensive along the Dutch frontier, before returning to the offensive in the third week of October, with the objective, after Tilburg and Breda had fallen to the 49th, being the capture of the town of Roosendaal, which fell after ten days of vicious fighting.[37] Major General Barker described the town as "not much of a place, bombed by USAF early in the year... We have crossed 20 miles in 10 days and had to fight every inch of it".[38] Further fighting continued until the division ended up at Willemstad at the Hollandsche Diep. The division then transferred from Lieutenant General Crocker's I Corps to Lieutenant General Neil Ritchie's XII Corps[6] and helped in the clearing of the west bank of the River Maas, along the Dutch border, fighting in very wet and muddy conditions.[39]

In late November the division suffered a blow when its GOC, Major General "Bubbles" Barker, who had continously commanded the division since April 1943, succeeded Lieutenant General O'Connor as the GOC of VIII Corps and left the division, subsequently receiving a promotion to lieutenant general. Barker's handling of the "Polar Bears", most notably during Operation Epsom in Normandy, had clearly impressed his superiors.[40] Barker later wrote that "My fortune was to command the Polar Bears whose achievements were made possible by its great efficiency at all levels, its high morale and the marvellous team work..... It was a splendid fighting machine".[41] Barker's successor was Major General Gordon MacMillan, formerly the GOC of the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division and, like his predeccesor, a distinguished veteran of the First World War.[4]

After the new GOC's assumption of command, the next few months for the division, now serving as part of II Canadian Corps,[6] commanded by Lieutenant General Guy Simonds, were spent mainly in small-scale skirmishing, including numerous patrols in attempts to dominate no man's land, and garrisoning the area between the River Waal and the Lower Rhine, also known as "The Island", created in the aftermath of the failed Operation Market Garden.[42] However, in late March 1945 the division, commanded now by Major General Stuart Rawlins after MacMillan was order to become GOC of the 51st (Highland) Division, received orders to clear "The Island", which, after much hard fighting but relatively light casualties, was cleared in early April, before advancing north-eastwards towards Arnhem. The 49th Division's last major contribution to the Second World War was the liberation of Arnhem and the fierce battles that led to it.[43] The division, now part of I Canadian Corps, under Lieutenant General Charles Foulkes,[6] and supported by Canadian tanks of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division, liberated the city at a cost of less than 200 casualties, but over 4,000 Germans became casualties.[44]

Just after the German surrender on 7 May 1945 the division played a part in the liberation of Utrecht, with the 49th Reconnaissance Regiment entering first, followed by Canadian troops. There is a monument dedicated to the Polar Bears at a spot on Biltstraat in the city. During the course of the Second World War the 49th Division suffered heavy casualties of 11,000 wounded or missing. 1,642 were killed in action.[45]

Order of battle

The 49th Infantry Division was constituted as follows during the war:[16]

- 4th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment

- 1/4th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

- Hallamshire Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

- 1/5th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment (left 7 September 1942)

- 1/6th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's Regiment (left 6 July 1944)

- 1/7th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's Regiment

- 147th Infantry Brigade Anti-Tank Company (formed 20 March 1940, disbanded 1 August 1941)

- 11th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers (from 8 September 1942)

- 1st Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment (from 6 July 1944)

148th Infantry Brigade (left 4 April 1940)[10]

- 1/5th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment

- 1/5th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters (until December 1939)

- 8th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters

- 2nd Battalion, South Wales Borderers (from 18 December 1939)

70th Infantry Brigade (from 18 May 1942, disbanded 20 August 1944)[14]

- 10th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry

- 11th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry

- 1st Battalion, Tyneside Scottish (Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment))

56th Infantry Brigade (from 20 August 1944)[46]

- 2nd Battalion, South Wales Borderers (left 27 April 1945, rejoined 14 June 1945)

- 2nd Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, Essex Regiment

- 7th Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers (from 28 April 1945, left 13 June 1945)

Divisional Troops

- 2nd Battalion, Princess Louise's Kensington Regiment (from 7 June 1943, joined as divisional support battalion, became machine gun battalion 28 February 1944)

- 49th Reconnaissance Regiment, Reconnaissance Corps (formed 5 September 1942, became 49th Reconnaissance Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps 1 January 1944)

- 69th (West Riding) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 70th (West Riding) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (until 6 August 1940)

- 71st (West Riding) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (until 6 August 1940)

- 79th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 8 until 23 June 1940)

- 80th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 8 until 23 June 1940)

- 143rd (Kent Yeomanry) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 26 April 1942)

- 178th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 15 May 1942)

- 185th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 24 December 1942, disbanded 29 November 1944)

- 74th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 30 November 1944)

- 58th (Duke of Wellington's) Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery (until 23 June 1940)

- 88th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 17 June 1942 until 24 July 1943)

- 55th (Suffolk Yeomanry) Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 26 July 1943)

- 118th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 5 July until 8 December 1942)

- 89th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 29 December 1942)

- 228th (West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers (until 30 September 1939)

- 229th (West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers (until 4 April 1940)

- 230th (West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers (until 4 April 1940)

- 294th Field Company, Royal Engineers (from 26 April 1942)

- 756th Field Company, Royal Engineers (from 26 April 1942)

- 757th Field Company, Royal Engineers (from 26 April 1942)

- 231st (West Riding) Field Park Company, Royal Engineers (until 4 April 1940)

- 289th Field Park Company, Royal Engineers (from 26 April 1942)

- 23rd Bridging Platoon, Royal Engineers (from 1 November 1943)

- 49th (West Riding) Divisional Signals Regiment, Royal Corps of Signals

Postwar

The division was disbanded in Germany in 1946, but reformed in the TA in 1947, having been renamed the 49th (West Riding) Armoured Division. It was based in Nottingham, consisting of (on 1 April 1947):

- 8 (Yorkshire) Armoured Brigade

- 146 (West Riding) Infantry Brigade

- 147 (Midland) Lorried Infantry Brigade

- Artillery included 269 and 270 Field Regiments Royal Artillery

In 1956, it was renamed the 49th (West Riding and Midland) Infantry Division, its base moved to Leeds, and the 8th Armoured Brigade was removed from its order of battle. Finally, it underwent its last major change in 1961, when it was renamed to the 49th (West Riding and North Midland) Division/District, and the 147th Infantry Brigade was removed from its composition. The Division/District finally disbanded in 1967, becoming simply X District.[47]

The polar bear flash was last worn by 49th Brigade, Under Army 2020, 49 (E) Brigade was merged with 7th Armoured Brigade to become 7th Infantry Brigade on 13 February 2015.[48]

Commanders

- Brigadier-General Archibald J.A. Wright: April 1908 – January 1910

- Lieutenant-General George M. Bullock: January 1910 – September 1911

- Major-General Thomas S. Baldock: September 1911 – July 1915

- Major-General Edward M. Perceval: July 1915 – October 1917

- Major-General Neville J.G. Cameron: October 1917 – June 1919

- Major-General Henry R. Davies: June 1919 – June 1923

- Major-General Alfred A. Kennedy: June 1923 – March 1926

- Major-General Neville J.G. Cameron: June 1926 – June 1930

- Major-General Reginald S. May: June 1930 – September 1931

- Major-General George H.N. Jackson: September 1931 – September 1935

- Major-General George C. Kelly: September 1935 – April 1938

- Major-General Pierse J. Mackesy: May 1938 - April 1940

- Major-General Henry O. Curtis: June 1940 - April 1943

- Major-General Evelyn H. Barker: April 1943 - November 1944

- Major-General Gordon H.A. MacMillan: November 1944 - March 1945

- Major-General Stuart B. Rawlins: March - August 1945

- Major-General E. Temple L. Gurdon: September 1945 – October 1946

- Major-General George W. Richards: January 1947 – December 1948

- Major-General Ronald B.B.B. Cooke: December 1948 – December 1951

- Major-General Reginald P. Harding: December 1951 – December 1954

- Major-General Ralph Younger: December 1954 – December 1957

- Major-General Richard E. Goodwin: December 1957 – July 1960

Victoria Cross recipients

- Corporal Samuel Meekosha, 1/6th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, Great War

- Corporal George Sanders, 1/7th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, Great War

- Private Arthur Poulter, 1/4th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment), Great War

- Corporal John Harper, Hallamshire Battalion, York and Lancaster, Second World War

Memorial

At the Site John McCrae just outside Ypres there is a memorial to the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division. It is located is immediately behind Essex Farm Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery, on top of the canal bank.[49] It is shaped like an obelisk and accessed via a flight of stairs leading up the canal bank from the cemetery.

See also

- List of British divisions in World War I

- List of British divisions in World War II

- British Army Order of Battle (September 1939)

- Berenkuil (traffic), a type of traffic circle that may have been named after the division

- 46th Infantry Division 2nd Line duplicate during World War II

Notes

- ↑ The image of a hunting polar bear, with its head down, looking for seals, was thought by the new General Officer Commanding (GOC), Major General Evelyn Barker, described as a "very vigorous and efficient general" and a "fire-eater", to be "a droopy timid-looking bear just like that one on those [Fox's] mints. I wanted a ferocious animal, with a snarl on its face", and had it replaced by the head up, more aggressive looking version.[2]

References

- 1 2 Cole p. 44

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 22

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "The 49th (West Riding) Division in 1914-1918". Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joslen, p. 79

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "badge, formation, 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division & Avonforce & Alabaster Force & Iceland Force". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Joslen, p. 80

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 1

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 4–11

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 12

- 1 2 Joslen, p. 333

- 1 2 Joslen, p. 331

- 1 2 Joslen, p. 332

- ↑ "John Crook's service in Iceland".

- 1 2 Joslen, p. 301

- 1 2 3 Delaforce, p. 19

- 1 2 Joslen, pps. 79–80

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 21

- 1 2 Delaforce, p. 23

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 24

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 26

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 26-27

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 50-55

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 56-57

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 62

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 63-71

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 100-109

- 1 2 Delaforce, p. 109

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 111-116

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 127-131

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 132-133

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 134

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 148-161

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 160

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 162-163

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 164-169

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 170-172

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 181-182

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 192

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 188-190

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 188-193

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 136

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 194-199

- ↑ Corry, p. 28

- ↑ Delaforce, pps. 213-226

- ↑ Delaforce, p. 236-237

- ↑ Joslen, p. 296

- ↑ "History". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ "49 (East) Brigade Officially Disbanded". Forces TV. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ CWGC: Essex Farm Cemetery, access date 2015-05-12

Bibliography

- Cole, Howard (1973). Formation Badges of World War 2. Britain, Commonwealth and Empire. London: Arms and Armour Press.

- Corry, Lieutenant G.D; Oglesby, Major R.B (1950-10-17). "Report No 39: Operations of 1 Canadian Corps in North-West Europe, 15 March - 5 May 1945" (PDF). National Defence and the Canadian Forces, Army Headquarters Reports 1948-1959. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- Delaforce, Patrick (1995). The Polar Bears: Monty's Left Flank: From Normandy to the Relief of Holland with the 49th Division. Stroud: Chancellor Press. ISBN 9780753702659.

- Lt-Col H.F. Joslen, Orders of Battle, United Kingdom and Colonial Formations and Units in the Second World War, 1939–1945, London: HM Stationery Office, 1960/Uckfield: Naval & Military, 2003, ISBN 1-84342-474-6.

External links

- The British Army in the Great War: The 49th (West Riding) Division

- Regiments.org Summary and Lineage

- Composition of the 49th Division

- Generals of World War II

- 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division Polar Bear Association

Further reading

- Magnus, L. (1920). The West Riding Territorials in the Great War (N & M Press 2004 ed.). London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner. ISBN 1-84574-077-7. Retrieved 22 October 2014.