Bristol Scout

- For the later monoplane, see Bristol M.1 Monoplane Scout

- For the unrelated 1917 prototype design, see Bristol Scout F

| Bristol Scout | |

|---|---|

| |

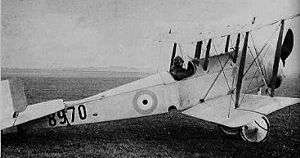

| RNAS Bristol Scout D of third production batch | |

| Role | single-seat scout/fighter |

| Manufacturer | British and Colonial Aeroplane Company |

| Designer | Frank Barnwell |

| First flight | 23 February 1914 |

| Primary users | Royal Flying Corps Royal Naval Air Service Australian Flying Corps |

| Produced | 1914–1916 |

| Number built | 374[1] |

The Bristol Scout was a single-seat rotary-engined biplane originally designed as a racing aircraft. Like similar fast, light aircraft of the period it was used by the RNAS and the RFC as a "scout", or fast reconnaissance type. It was one of the first single-seaters to be used as a fighter aircraft, although it was not possible to fit it with an effective forward-firing armament until the first British synchronisation gears became available, by which time the Scout was obsolescent. Single-seat fighters continued to be called "scouts" in British usage into the early 1920s.[1]

Background

The Bristol Scout was designed in the second half of 1913 by Frank Barnwell and Harry Busteed, Bristol's chief test pilot, who thought of building a small high-performance biplane while testing the Bristol X.3 seaplane, a project which had been designed by a separate secret design department headed by Barnwell. The design was initially given the works number SN.183, inherited from a cancelled design for the Italian government undertaken by Henri Coanda, the half-finished fuselage of which remained in the workshops and the drawings for the aircraft bore this number.[2]

Design and development

The design was an equal-span single-bay biplane with staggered parallel-chord wings with raked wingtips and ailerons fitted to the upper and lower wings, which were rigged with about half a degree of dihedral, making them look almost straight when viewed from the front. The wing section was one designed by Coanda which had been used for the wings of the Bristol Coanda Biplanes.[3] The rectangular-section fuselage was an orthodox wire-braced wooden structure constructed from ash and spruce, with the forward section covered with aluminium sheeting and the rear section fabric covered.[3] It was powered by an 80 hp (60 kW) Gnome Lambda rotary engine enclosed in a cowling that had no open frontal area, although the bottom was cut away to allow cooling air to get to the engine.[4] It had a rectangular balanced rudder with no fixed fin and split elevators attached to a non-lifting horizontal stabiliser. The fixed horizontal tail surfaces were outlined in steel tube with wooden ribs and the elevators constructed entirely of steel tube.[5]

The first flight was made at Larkhill on 23 February 1914 by Busteed and it was then exhibited at the March 1914 Aero Show at Olympia in London. After more flying at Larkhill the prototype, later referred to as the Scout A, was returned to the factory at Filton and fitted with larger wings, increasing the chord by six inches (15 cm) and the span from 22 ft (6.71 m) to 24 ft 7 in (7.49 m). These were rigged with an increased dihedral of 1 3⁄4°. Other changes included a larger rudder, a new open-fronted cowling with six external stiffening ribs distributed in symmetrically uneven angles around the cowl's sides (especially when seen from "nose-on")[6] and fabric panel-covered wheels. It was evaluated by the British military on 14 May 1914 at Farnborough, when, flown by Busteed, the aircraft achieved an airspeed of 97.5 mph (157 km/h), with a stalling speed of 40 mph (64 kph)[7] The aircraft was then entered for the 1914 Aerial Derby but did not take part because the weather on the day of the race was so poor that Bristol did not wish to risk the aircraft. By this time two more examples (works nos. 229 and 230) were under construction and the prototype was sold to Lord Carbery for £400 without its engine. Carbery fitted it with an 80 hp Le Rhône 9C nine-cylinder rotary and entered it in the London–Manchester race held on 20 June but damaged the aircraft when landing at Castle Bromwich and had to withdraw. After repairs, including a modification of the undercarriage to widen the track, Carbury entered it in the London–Paris–London race held on 11 July but had to ditch the aircraft in the English Channel on the return leg; while in France, only one of the two fuel tanks had been filled by mistake. Carbury managed to land alongside a ship and escaped but the aircraft was lost.[8]

Numbers 229 and 230, later designated the Scout B when Frank Barnwell retrospectively gave type numbers to early Bristol aircraft, were identical to the modified Scout A, except for having half-hoop-style underwing skids and an enlarged rudder. Completed shortly after the outbreak of war in August 1914, they were requisitioned by the War Office. Given Royal Flying Corps serial numbers 644 and 648, one was allocated to No. 3 Squadron and the other to No. 5 Squadron for evaluation.[1] Number 644 was damaged beyond repair on 12 November 1914 in a crash landing.

Impressed by the performance of the aircraft, the War Office ordered twelve examples on 5 November and the Admiralty ordered a further 24 on 7 November.[9] The production aircraft, later called the Scout C, differed from their predecessors mainly in constructional detail, although the cowling was replaced by one with a small frontal opening and no stiffening ribs, the top decking in front of the cockpit had a deeper curve and the aluminium covering of the fuselage sides extended only as far as the forward centre-section struts, aft of which the decking was plywood.[7]

Operational history

The period of service of the Bristol Scout (1914–1916) marked the genesis of the fighter aircraft as a distinct type and many of the earliest attempts to arm British tractor configuration aircraft with forward-firing guns were tested in action using Bristol Scouts. These began with the arming of the second Scout B, RFC number 648, with two rifles, one each side, aimed outwards and forwards to clear the propeller arc.[1][10]

Two of the Royal Flying Corps' early Bristol Scout C aircraft, numbers 1609 and 1611, flown by Captain Lanoe Hawker with No. 6 Squadron RFC, were in turn armed with a Lewis machine gun on the left side of the fuselage, almost identical to the manner of the rifles tried on the second Scout B. using a mount that Hawker had designed. When Hawker downed two German aircraft and forced off a third on 25 July 1915 over Passchendaele and Zillebeke he was awarded the first Victoria Cross for the actions of a British military pilot in aerial combat.[11]

Some of the 24 initial production Scout Cs for the RNAS, were armed with one (or occasionally two) Lewis machine guns, sometimes with the Lewis gun mounted on top of the upper wing centre section in the manner of the Nieuport 11; more common was a very dubious choice of placement by some RNAS pilots, in mounting the Lewis gun on the forward fuselage of their Scout Cs, just as if it were a synchronized weapon, firing directly forward and through the propeller arc, an action likely to result in serious damage to the propeller. The type of bullet-deflecting wedges that Roland Garros had tried on his Morane-Saulnier Type N monoplane were also tried on one of the RFC's last Scout Cs, No. 5303 but since this seemed to have also required the use of the Morane Type N's immense "casserole" spinner, which almost totally blocked cooling air from reaching the engine, the deflecting-wedge method was not pursued further with Bristol Scouts.[1][12][13]

An RNAS Scout was the first landplane to be flown from a ship, when Flt. Lt. H. F. Towler flew No. 1255 from the flying deck of the seaplane carrier HMS Vindex on 3 November 1915.[14] As an attempted defence against German airships, some RNAS Scout Ds were equipped with Ranken Darts, a flechette with 1 lb (0.45 kg) of explosive per projectile, released from a pair of vertical cylindrical containers under the pilot's seat, each containing 24 darts.[15] On 2 August 1916, Flt. Lt. C. T. Freeman flew a Scout from the deck of Vindex and attacked Zeppelin L 17 with Ranken Darts. None of the darts did any damage to the Zeppelin, and since Freeman's aircraft could not land on the Vindex and was too far from land for a safe return, he had to ditch his Scout D after the attack.[16]

.jpg)

In March 1916, RFC Scout C No.5313 was fitted with a Vickers machine gun, synchronised to fire through the propeller by the awkward Vickers-Challenger synchronising gear, the only gear available to the RFC. Six other Scouts, late Scout Cs and early Scout Ds, were also fitted with the same combination. Types using this gear (including the B.E.12, the R.E.8 and the Vickers F.B.19) all had the gun mounted on the port side of the fuselage. The attempt to use the gear for synchronising a centrally mounted gun on the Bristol Scout failed and tests, which continued at least until May 1916, resulted in the abandonment of the idea and no Vickers-armed Bristol Scouts were used in operations.[1]

None of the RFC or RNAS squadrons operating the Bristol Scout were exclusively equipped with this aircraft and by the end of the summer of 1916, no new Bristol Scout aircraft were being supplied to the British squadrons of either service, the early fighter squadrons in RFC service being equipped instead with the Airco DH.2 single-seat Pusher configuration fighter. A small number of Bristol Scouts were sent to the Middle East (in Egypt, Mesopotamia and Palestine) in 1916. Others served in Macedonia and with the RNAS in the Eastern Mediterranean. The last known Bristol Scout in military service was the former RNAS Scout D No. 8978 in Australia, which was based at Point Cook, near Melbourne, as late as October 1926.

Once the Bristol Scouts were no longer required for frontline service they were reallocated to training units, although many were retained by senior officers as personal "runabouts".

Variants

Scout A

The single prototype aircraft.

Scout B

Two manufactured, identical to the modified Scout A except for having half-hoop-style underwing skids and an enlarged rudder.

Type 1 Scout C

Similar to the previous Scout B. These early Scout Cs also had their main oil tank moved to a position directly behind the pilot's shoulders, requiring a raised rear dorsal fairing immediately behind the pilot's seat to accommodate it.[1]

Following the initial run of 36 Scout C airframes (12 for RFC, 24 for RNAS) later Scout C production batches, consisting of 50 aircraft built for the RNAS and 75 for the RFC, changed the cowl to a flat-fronted longer-depth version able to house the alternate choice of a nine-cylinder 80 hp Le Rhône 9C rotary engine when the Gnome Lambda was not used, and moved the oil tank forward to a position in front of the pilot for better weight distribution and more reliable engine operation. The later cowl for the remaining Scout C aircraft still had the small opening of the domed unit, but often had a small cutaway made to the lower rear edge of the cowl to increase the cooling effect, and to allow any unburned fuel/oil mix to drain away.[1] A total of some 161 Scout C airframes were produced for the British military as a whole, with the transition to the Scout D standard taking place in a gradual progression of feature changes.

Types 2, 3, 4 and 5 Scout D

The last, and most numerous production version, the Scout D, gradually came about as the result of a series of further improvements to the Scout C design. One of the earliest changes appeared on seventeen of the 75 naval Scout Cs with an increase in the wing dihedral angle from 1 3⁄4° to 3° and other aircraft in the 75 aircraft naval production run introduced a larger span horizontal tail surfaces and a broadened-chord rudder, shorter-span ailerons and a large front opening for the cowl, much like that of Scout B but made as a "one-piece" ring cowl instead.[17]

The newer cowl was sometimes modified with a blister on the starboard lower side for more efficient exhaust-gas scavenging, as it was meant to house the eventual choice of the more powerful, nine-cylinder 100 hp Gnôme Monosoupape B2 rotary engine in later production batches, to improve the Scout D's performance. Some 210 examples of the Scout D version were produced, with 80 of these being ordered by the RNAS and the other 130 being ordered by the Royal Flying Corps.[1][18]

Other variants

- S.2A : Two-seat fighter version of the Scout D. Two were built as advanced training aircraft.[1]

Operators

- Australian Flying Corps

- No. 1 Squadron AFC in Egypt and Palestine.

- No. 6 (Training) Squadron AFC in the United Kingdom.

- Central Flying School AFC at Point Cook, Victoria.

Specifications (Bristol Scout D)

Data from Bristol Aircraft since 1910[1]

General characteristics

- Crew: one

- Length: 20 ft 8 in (6.30 m)

- Wingspan: 24 ft 7 in (7.49 m)

- Height: 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m)

- Wing area: 198 ft² (18.40 m²)

- Empty weight: 789 lb (358 kg)

- Loaded weight: 1,195 lb (542 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Le Rhône 9C rotary piston engine, 80 hp (60 kW)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 94 mph (151 km/h)

- Service ceiling: 16,000 ft (4,900 m)

- Rate of climb: 18 min 30 sec to 10,000 ft (18 min 30 sec to 3,048 m)

- Power/mass: 0.067 hp/lb (0.11 kW/kg)

- Combat endurance: 2½ hours

Armament

- 1 × Lewis or Vickers machine gun

See also

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Barnes 1964

- ↑ Barnes 1970, p.91

- 1 2 The 80 h.p. Bristol "Scout", Flight, 25 April 1914, pp.434-6

- ↑ Bruce, J. M. (1994). Windsock Datafile No.44, The Bristol Scouts. Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros Publications. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-948414-59-6.

- ↑ Rebuilding Grandad's Scout 18 Dec 1913. Wednesday access date 28 March 2015

- ↑ Bruce, J. M. (1994). Windsock Datafile No.44, The Bristol Scouts. Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros Publications. p. 5. ISBN 0-948414-59-6.

- 1 2 Bruce, J. M.The Bristol Scout Part 1, Flight International, 26 September 1958, pp. 525–8

- ↑ Barnes 1970, pp92–3

- ↑ Barnes 1970, p. 94

- ↑ Bruce, J. M. (1994). Windsock Datafile No.44, The Bristol Scouts. Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros Publications. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-948414-59-6.

- ↑ Bruce, J. M. (1994). Windsock Datafile No.44, The Bristol Scouts. Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros Publications. pp. 5, 6. ISBN 0-948414-59-6.

- ↑ Bruce, J. M. (1994). Windsock Datafile No.44, The Bristol Scouts. Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros Publications. pp. 10, 11. ISBN 0-948414-59-6.

- ↑ Shores and Rolfe 2001, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Bruce, J. M.The Bristol Scout Pt II Flight International 3 October 1958, pp. 544–6

- ↑ Bruce, J. M. The Bristol Scout Part V Flight International, 31 October 1958, pp.701–11

- ↑ Bruce, J. M. (1994). Windsock Datafile No.44, The Bristol Scouts. Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros Publications. p. 5. ISBN 0-948414-59-6.

- ↑ Bruce, J. M. (1994). Windsock Datafile No.44, The Bristol Scouts. Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros. p. 8. ISBN 0-948414-59-6.

- ↑ "Bristol Scout D." Fleet Air Arm Museum. Retrieved: 18 October 2011.

Bibliography

- Barnes, C. H. Bristol Aircraft since 1910. London: Putnam, 1964.

- Barnes, C. H. Bristol Aircraft since 1910. (second ed.) London: Putnam, 1970. ISBN 0 370 00015 3

- Bruce, J. M. The Bristol Scouts (Windsock Datafile No.44). Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros, 1994. ISBN 0-948414-59-6.

- Shores, Christopher and Rolfe, Mark. British and Empire Aces of World War 1. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2001. ISBN 978-1-84176-377-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bristol Scout. |

- "TheAerodrome.com's" Bristol Scout page

- The Bristol Scout By Chris Banyai-Riepl

- Bristol Scout: Rebuilding Granddad's Aircraft (No. 1264 of the RNAS)