Bristol Proteus

| Proteus | |

|---|---|

| |

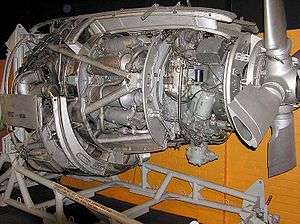

| Preserved Bristol Proteus | |

| Type | Turboprop |

| Manufacturer | Bristol Siddeley |

| First run | 25 January 1947 |

| Major applications | Bristol Britannia, Saunders-Roe Princess |

The Bristol Proteus was the Bristol Aeroplane Company's first successful gas turbine engine design, a turboprop that delivered just over 4,000 hp (3,000 kW). The Proteus was a two spool, reverse-flow gas turbine. Because the turbine stages of the inner spool drove no compressor stages, but only the propeller, this engine was classified as a free-turbine. It powered the Bristol Britannia airliner, small naval patrol craft, hovercraft and electrical generating sets. It was also used to power a land-speed record car, the Bluebird-Proteus CN7. After the merger of Bristol with Armstrong Siddeley the engine became the Bristol Siddeley Proteus, and later the Rolls-Royce Proteus.

Design and development

Design work on the Proteus started in September 1944, during the course of development the gas generator section was built as a small turbojet which became known as the Bristol Phoebus. This engine was test flown in May 1946 fitted to the bomb bay of an Avro Lincoln, performance was poor due to airflow problems. The 2-stage centrifugal compressor was replaced but similar problems were encountered when the Proteus started ground testing on 25 January 1947.[1]

The original Proteus Mk.600 delivered 3,780 hp (2,820 kW), and was going to be used on the early versions of the Britannia and the Saunders-Roe Princess flying-boat. The versions on the Princess were mounted in a large frame driving a single propeller through a gearbox, and were known as the Coupled Proteus. The Coupled Proteus was also intended to be used on the Mk.II versions of the Bristol Brabazon, but this project was cancelled. Only three Princesses were built, only one of which flew, and by the time the Britannia was ready for testing the manufacturer had decided to equip it with the later Mk.700 Proteus instead.

During development, there were severe problems with compressor blades, turbine blades and bearings failing at even low power output levels. This led to the famous quote of Proteus Chief Engineer Frank Owner to Chief Engineer of the Engine Division Stanley Hooker: "You know, Stanley, when we designed the Proteus I decided we should make the engine with the lowest fuel consumption in the world, regardless of its weight and bulk. So far, we have achieved the weight and bulk!"[2]

At this point the Proteus proved to have troubling icing problems, causing the engine and aircraft projects to be delayed while solutions were found. The Mk.705 of 3,900 hp (2,900 kW) was the first version to see widespread production on the Bristol Britannia 100 and some 300 series. The Mk.755 of 4,120 hp (3,070 kW) was used on the 200 series (not built) and other 300's, and the Mk.765 of 4,445 hp (3,315 kW) was used on the RAF's Series 250 aircraft.

Variants

As with most gas turbine engines of the 1940s, 50s, and 60s the Ministry of Supply allocated the Proteus a designation which was apparently little used. Officially the Proteus was named Bristol BPr.n Proteus

- Bristol Phoebus

- (BPh.1) Turbojet early version of the Proteus used to test and develop the gas generator portion of the engine, flight tested in the bomb bay of an Avro Lincoln from May 1946.

- Proteus series 1

- (BPr.1)Prototype and early production engines used for development and testing.

- Proteus series 2

- Initial production versions, renamed as Proteus 600 series engines.[3][4]

- Proteus series 3

- The fully developed initial version, renamed as the Proteus 700 series.[4]

- Proteus 600

- Initial production engines renamed from Proteus series 2.

- Proteus 610

- The engines used in the Coupled-Proteus installations for the Saunders-Roe Princess flying boat.[4]

- Proteus 625

- Proteus 700

- Proteus 705

- The engine used among others in the Bluebird-Proteus CN7 land speed record-breaking car.

- Proteus 710

- The engines slated for use in the Coupled-Proteus installations of the Bristol Brabazon Mk.II airliner.

- Proteus 750

- [3]

- Proteus 755

- [3]

- Proteus 756

- [3]

- Proteus 757

- [3]

- Proteus 758

- [3]

- Proteus 760

- [3]

- Proteus 761

- [3]

- Proteus 762

- [3]

- Proteus 765

- [3]

- Proteus Mk.255

- Military engines similar to the Proteus 765, to power the Bristol 253 Britannia C.Mk.1.[3]

- Coupled-Proteus 610

- Twin Proteus 600 series engines driving contra-rotating propellers through a combining gearbox, developed specifically for the Saunders-Roe SR.45 Princess.[4]

- Coupled-Proteus 710

- Twin Proteus 710 engines driving contra-rotating propellers for the Bristol Brabazon I Mk.II.

- Marine Proteus

- Marinised Proteus engines have been used to power ships and hovercraft such as the Brave-class fast patrol boat and the SR.N4 hovercraft.

- Industrial Proteus

- Used for industrial applications such as power generation, notably by the South Western Electricity Board in Pocket Power Plants, the world's first unmanned electricity generation stations.[5]

- Bluebird Proteus

- A specially modified Proteus 705 with drive shafts at front and rear of the engine to drive front and rear differential gearboxes on Donald Campbell's Bluebird-Proteus CN7.

Applications

Aircraft

Other applications

After testing on the frigate HMS Exmouth a marinised Proteus engine was used to power the Royal Navy's Brave-class fast patrol boats, and subsequently in many fast patrol boats of similar design built for export by Vosper. These were among the fastest warships ever built, achieving over 50 knots on flat water. The Swedish torpedo boat Spica and her sisters were also powered by the Proteus.

The Proteus was used on the SR.N4 Mountbatten-class cross-Channel hovercraft. In this installation four "Marine Proteus" engines were clustered in the rear of the craft, exhausts pointed rearward. The engines drove horizontal power shafts that delivered power to one of four "pylons" positioned at the corners of the boat. At the pylons, gearboxes used the horizontal torque to power a vertical shaft, with a lift fan at the bottom and propeller at the top. The two at the front required long shafts that ran over the passenger cabin.[6]

Pocket Power Stations

Another use of the Proteus was for remote power generation in the South West of England in what were called "Pocket Power Stations".[7][8] The regional electricity board installed several 2.7MW remote operated generation sets for peak load powered by the Proteus. Designed to run for ten years many were still in use forty years later.[9] A working example is preserved at the Internal Fire - Museum of Power in West Wales.

Specifications (Proteus Mk.705)

Data from Flight.[10]

General characteristics

- Type: Turboprop

- Length: 113 in (2,870 mm)

- Diameter: 39.5 in (1,003 mm)

- Dry weight: 2,850 lb (1293 kg)

Components

- Compressor: Single 12-stage axial, followed by a single centrifugal stage

- Combustors: Reverse-flow

- Turbine: Two-stage power (free turbine), two-stage driving compressor

- Fuel type: Aviation kerosene

Performance

- Maximum power output: 3,320 shp (2,475 kW) + 1,200 lb (5.33 kN) residual thrust giving 3,780 eshp

- Overall pressure ratio: 7.2:1

- Air mass flow: 44 lb/s (20 kg/s)

- Fuel consumption: 273 Imp gal (1,241 L) /hour

- Specific fuel consumption: 0.495 lb/h/eshp

- Power-to-weight ratio: 1.32 eshp/lb

See also

- Comparable engines

- Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ Gunston 1989, p.35.

- ↑ Hooker, 1985, p.128.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Taylor, John W.R. FRHistS. ARAeS (1962). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1962-63. London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co Ltd.

- 1 2 3 4 5 London, Peter (1988). Saunders and Saro Aircraft since 1917. London: Conway Maritime Press Ltd,. pp. 210–235. ISBN 0 85177 814 3.

- ↑ Gale, John. "SWEB's Pocket Power Stations". South Western Electricity Historical Society. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ "BHC/Saunders Roe SRN4 Mountbatten Class", James' Hovercraft Site

- ↑ South Western Electricity Historical Society. "SWEB's Pocket Power Stations". Internal Fire - Museum of Power. Archived from the original on 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "Pocket Power Station". A History of the World. BBC.

- ↑ "Pocket Power Station wins award". BBC Mid Wales. 11 June 2010.

- ↑ Flightglobal archive - Flight 9 April 1954 Retrieved: 28 July 2009

Bibliography

- "Pocket Power Station wins award". BBC Mid Wales. 11 June 2010.

- Taylor, John W.R. FRHistS. ARAeS (1962). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1962-63. London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co Ltd.

- London, Peter (1988). Saunders and Saro Aircraft since 1917. London: Conway Maritime Press Ltd,. pp. 210–235. ISBN 0 85177 814 3.

- Gunston, Bill. World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines. Cambridge, England. Patrick Stephens Limited, 1989. ISBN 1-85260-163-9

- Hooker, Sir Stanley. Not Much Of An Engineer. Airlife Publishing, 1985. ISBN 1-85310-285-7.

- Gale, John. "SWEB's Pocket Power Stations". South Western Electricity Historical Society. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- "Aero Engines 1954", Flight, Flightglobal archive, 9 April 1954, retrieved 28 July 2009

Further reading

- Bridgman, Leonard, ed. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1951–1952. London: Samson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd 1951.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bristol Proteus. |

- SWEB's Pocket Power Stations

- Bristol Engine data

- "Advert by Bristol for the Proteus 755 and Britannia" (PDF). Flight. 19 February 1954., A sectional view of Proteus 755 turboprop, showing gasflow paths

- "Power for the Giants" a 1948 Flight article

- "Bristol Proteus" a 1949 Flight article on the Proteus