Brazilian cuisine

|

| Part of a series on |

| Brazilian cuisine |

|---|

| Types of food |

| See also |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Brazil |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

Brazilian cuisine has European, African and Amerindian influences.[1] It varies greatly by region, reflecting the country's mix of native and immigrant populations, and its continental size as well. This has created a national cuisine marked by the preservation of regional differences.[2]

Ingredients first used by native peoples in Brazil include cassava, guaraná, açaí, cumaru, cashew and tucupi. From there, the many waves of immigrants brought some of their typical dishes, replacing missing ingredients with local equivalents. For instance, the European immigrants (primarily from Portugal, Italy, Spain, Germany, Poland and Switzerland) were accustomed to a wheat-based diet, and introduced wine, leafy vegetables, and dairy products into Brazilian cuisine. When potatoes were not available they discovered how to use the native sweet manioc as a replacement.[3] Enslaved Africans also had a role in developing Brazilian cuisine, especially in the coastal states. The foreign influence extended to later migratory waves – Japanese immigrants brought most of the food items that Brazilians would associate with Asian cuisine today,[4] and introduced large-scale aviaries, well into the 20th century.[5]

Root vegetables such as cassava (locally known as mandioca, aipim or macaxeira, among other names), yams, and fruit like açaí, cupuaçu, mango, papaya, guava, orange, passion fruit, pineapple, and hog plum are among the local ingredients used in cooking.

Some typical dishes are feijoada, considered the country's national dish;[6] and regional foods such as beiju, feijão tropeiro, vatapá, moqueca, polenta (from Italian cuisine) and acarajé (from African cuisine).[7] There is also caruru, which consists of okra, onion, dried shrimp, and toasted nuts (peanuts or cashews), cooked with palm oil until a spread-like consistency is reached; moqueca capixaba, consisting of slow-cooked fish, tomato, onions and garlic, topped with cilantro; and linguiça, a mildly spicy sausage.

The national beverage is coffee, while cachaça is Brazil's native liquor. Cachaça is distilled from sugar cane and is the main ingredient in the national cocktail, caipirinha.

Cheese buns (pães-de-queijo), and salgadinhos such as pastéis, coxinhas, risólis (from pierogy of Polish cuisine) and kibbeh (from Arabic cuisine) are common finger food items, while cuscuz branco (milled tapioca) is a popular dessert.

Regional cuisines

There is not an exact single "national Brazilian cuisine", but there is an assortment of various regional traditions and typical dishes. This diversity is linked to the origins of the people inhabiting each dam.

For instance, the culinary in Bahia is heavily influenced by a mix of African, Indigenous and Portuguese cuisines. Chili (including chili sauces) and palm oil are very common. But in the Northern states, due to the abundance of forest and freshwater rivers, fish and cassava are staple foods. In the deep south like Rio Grande do Sul, the influence shifts more towards gaúcho traditions shared with its neighbors Argentina and Uruguay, with many meat based products, due to this region livestock based economy – the churrasco, a kind of barbecue, is a local tradition.

Southeast Brazil's cuisine

In Rio, São Paulo and Minas Gerais, the Brazilian Feijoada (a black bean and meat stew rooted, recipe registered for the first time in Recife, state of Pernambuco) is popular especially as a Wednesday or Saturday lunch. Also consumed frequently is picadinho (literally, diced meat) or rice and beans.[8][9]

In Rio de Janeiro, besides the feijoada, a popular plate is any variation of grilled bovine fillet, rice and beans, farofa and French fries, commonly called Filé à Osvaldo Aranha. Seafood is very popular in coastal areas, as is roasted chicken (galeto).

In São Paulo, a typical dish is virado à paulista, made with rice, tutu de feijão, sauteed kale, and pork. São Paulo is also the home of pastel, a food consisting of thin pastry envelopes wrapped around assorted fillings, then deep fried in vegetable oil. It is a common belief that they originated when Japanese immigrants adapted the recipe of fried spring rolls to sell as snacks at weekly street markets.

In Minas Gerais, the regional dishes include corn, pork, beans, chicken (including the very typical dish frango com quiabo, or chicken with okra), tutu de feijão (paste of beans and cassava flour), and local soft ripened traditional cheeses.

In Espírito Santo, there is significant Italian and German influence in local dishes, both savory and sweet. The state dish, though, is of Amerindian origin, called moqueca capixaba which is a tomato and fish stew prepared in a Panela de Barro(clay pot). Amerindian and Italian cuisine are the two main pillars of Capixaba cuisine. Seafood dishes in general are very popular in Espírito Santo but unlike other Amerindian dishes the use of olive oil is almost mandatory. Bobó de camarão, Torta Capixaba, Polenta are also very popular.

North Brazil's cuisine

The cuisine of this region, which includes the states of Acre, Amazonas, Amapá, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, and Tocantins, is heavily influenced by indigenous cuisine. In the state of Pará, there are several typical dishes including:

Pato no tucupi (duck in tucupi) – one of the most famous dishes from Pará. It is associated to the Círio de Nazaré, a great local Roman Catholic celebration. The dish is made with tucupi (yellow broth extracted from cassava, after the fermentation process of the broth remained after the starch had been taken off, from the raw ground manioc root, pressed by a cloth, with some water; if added maniva, the manioc ground up external part, that is poisonous because of the cyanic acid, and so must be cooked for several days). The duck, after cooking, is cut into pieces and boiled in tucupi, where is the sauce for some time. The jambu is boiled in water with salt, drained and put on the duck. It is served with white rice and manioc flour and corn tortillas

Center-West Brazil's cuisine

In the state of Goiás, the pequi is used in a lot of typical foods, specially the "arroz com pequi" (rice cooked with pequi), and in snacks, mostly as a filling for pastel. Also, a mixture of chicken and rice known as galinhada is very popular.

Northeast Brazil's cuisine

The Brazilian Northeastern cuisine is heavily influenced by African cuisine from the coastal areas of Pernambuco to Bahia, as well as the eating habits of indigenous populations that lived in the region.

The vatapá is a Brazilian dish made from bread, shrimp, coconut milk, finely ground peanuts and palm oil mashed into a creamy paste.

The Bobó de camarão is a dish made with cassava and shrimp (camarão).

The acarajé is a dish made from peeled black-eyed peas formed into a ball and then deep-fried in dendê (palm oil). Often sold as street food, it is served split in half and then stuffed with vatapá and caruru.[10] Acarajé is typically available outside of the state of Bahia as well, including the markets of Rio de Janeiro.

In other areas, more to the west or away from the coast, the plates are most reminiscent of the indigenous cuisine, with many vegetables being cultivated in the area since before the arrival of the Portuguese. Examples include baião de dois, made with rice and beans, dried meat, butter, queijo coalho and other ingredients. Jaggery is also heavily identified with the Northeast, as it is carne-de-sol, paçoca de pilão, and bolo de rolo.

Tapioca flatbreads or pancakes are also commonly served for breakfast in some states, with a filling of either coconut, cheese or condensed milk, among others.

Southern Brazil's cuisine

In Southern Brazil, due to the long tradition in livestock production and the heavy German immigration, red meat is the basis of the local cuisine.[11]

Besides many of the pasta, sausage and dessert dishes common to continental Europe, churrasco is the term for a barbecue (similar to the Argentine, Uruguayan, Paraguayan and Chilean asado) which originated in southern Brazil. It contains a variety of meats which may be cooked on a purpose-built "churrasqueira", a barbecue grill, often with supports for spits or skewers. Portable "churrasqueiras" are similar to those used to prepare the Argentine, Chilean, Paraguayan and Uruguayan asado, with a grill support, but many Brazilian "churrasqueiras" do not have grills, only the skewers above the embers. The meat may alternatively be cooked on large metal or wood skewers resting on a support or stuck into the ground and roasted with the embers of charcoal (wood may also be used, especially in the State of Rio Grande do Sul).

Since gaúchos were nomadic and lived off the land, they had no way of preserving food, the gauchos would gather together after butchering a cow, and skewer and cook the large portions of meat immediately over a wood burning fire. The slow-cooked meat basted in its own juices and resulted in tender, flavorful steaks. This style would carry on to inspire many contemporary churrascaria which emulate the cooking style where waiters bring large cuts of roasted meat to diners' tables and carve portions to order.[12]

The chimarrão is the regional beverage, often associated with the gaúcho image.

Popular dishes

- Rice and beans is an extremely popular dish, considered basic at table; a tradition Brazil shares with several Caribbean nations. Brazilian rice and beans usually are cooked utilizing either lard or the nowadays more common edible vegetable fats and oils, in a variation of the Mediterranean sofrito locally called refogado which usually includes garlic in both recipes.

- In variation to rice and beans, Brazilians usually eat pasta (including spaghetti, lasagne, yakisoba, lamen, and bīfun), pasta salad, various dishes using either potato or manioc, and polenta as substitutions for rice, as well as salads, dumplings or soups of green peas, chickpeas, black-eyed peas, broad beans, butter beans, soybeans, lentils, moyashi (which came to Brazil due to the Japanese tradition of eating its sprouts), azuki, and other legumes in substitution for the common beans cultivated in South America since Pre-Columbian times. It is more common to eat substitutions for daily rice and beans in festivities such as Christmas and New Year's Eve (the tradition is lentils), as follow-up of churrasco (mainly potato salad/carrot salad, called maionese, due to the widespread use of both industrial and home-made mayonnaise, which can include egg whites, raw onion, green peas, sweetcorn or even chayote squashes, and pronounced almost exactly as in English and French) and in other special occasions.

- Either way the basis of Brazilian daily cuisine is the starch (most often a cereal), legume, protein and vegetable combination. There is also a differentiation between vegetables of the verduras group, or greens, and the legumes group (no relation to the botanic concept), or non-green vegetables. There are Brazilians which eat both daily or the most often they can, only vegetables of one group, or none at all, which again depends on personal tastes.

- Salgadinhos are small savoury snacks (literally salties). Similar to Spanish tapas, these are mostly sold in corner shops and a staple at working class and lower middle-class familiar celebrations. There are many types of pastries:

- Pão de queijo (literally "cheese bread"), a typical Brazilian snack, is a small, soft roll made of manioc flour, eggs, milk, and minas cheese. It can be bought ready-made at a corner store or frozen and ready to bake in a supermarket and is gluten-free.

- Coxinha is a chicken croquette shaped like a chicken thigh.

- Kibe/Quibe: extremely popular, it corresponds to the Lebanese dish kibbeh and was brought to mainstream Brazilian culture by Syrian and Lebanese immigrants. It can be served baked, fried, or raw.

- Esfiha: another Middle Eastern dish, despite being a more recent addition to Brazilian cuisine they are nowadays easily found everywhere, specially in Northeastern, Southern and Southeastern regions. They are pies/cakes with fillings like beef, mutton, cheese curd, or seasoned vegetables.

- Pastéis are pastries with a wide variety of fillings. Similar to Spanish fried Empanadas but of Japanese origin (and brought to Brazil by the Japanese diaspora). Different shapes are used to tell apart the different flavours, the two most common shapes being half-moon (cheese) and square (meat). Size, flavour, and shape may vary greatly.

- Empadas are snacks that resemble pot pies in a small scale. Filled with a mix of palm hearts, peas, flour and chicken or shrimp.

- Misto-quente is grilled ham and cheese sandwich.

- Cuscuz branco is a dessert consisting of milled tapioca cooked with coconut milk and sugar and is the couscous equivalent of rice pudding.

- Açaí, cupuaçu, carambola, and many other tropical fruits are shipped from the Amazon Rainforest and consumed in smoothies or as fresh fruit. Other aspects of Amazonian cuisine are also gaining a following.

- Cachorro-quente is the Brazilian version of hot-dogs, usually garnished with tomato sauce, corn, peas and potato chips.

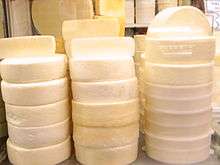

- Cheese: the dairy-producing state of Minas Gerais is known for such cheeses as Queijo Minas, a soft, mild-flavored fresh white cheese usually sold packaged in water; requeijão, a mildly salty, silky-textured, spreadable cheese sold in glass jars and eaten on bread; and Catupiry, a soft processed cheese sold in a distinctive round wooden box.

- Pinhão is the pine nut of the Araucaria angustifolia, a common tree in the highlands of southern Brazil. The nuts are boiled and eaten as a snack in the winter months. It is typically eaten during the festas juninas.

- Risoto (risotto) is a rice dish cooked with chicken, shrimp, and seafood in general or other protein staples sometimes served with vegetables, another very popular dish in Southern Brazil.

- Mortadella sandwich

- Sugarcane juice, mixed with fruit juices such as pineapple or lemon.

- Angu is a popular side dish (or a substitution for the rice fulfilling the "starch element" of use common in Southern and Southeastern Brazil). It is similar to the Italian polenta.

- Arroz com pequi is a traditional dish from the Brazilian Cerrado, and the symbol of Center-Western Brazil's cuisine. It is basically made with rice seasoned on pequi, also known as a souari nut, and often chicken.

- Sopa de Macaco

Also noteworthy are:

- Special ethnic foods and restaurants that are frequently found in Brazil include Arab cuisine (Lebanese and Syrian), local variations of Chinese cuisine (nevertheless closer to the traditional than American Chinese cuisine), Italian cuisine, and Japanese cuisine (sushi bars are a constant in major metropolises, and people from Rio de Janeiro are more used to temaki than people from São Paulo, home of more than 70% of the Japanese diaspora in the country).

- Pizza is also extremely popular. It is usually made in a wood-fire oven with a thin, flexible crust, little or very little sauce, and a number of interesting toppings. In addition to the "traditional" Italian pizza toppings, items like guava cheese and Minas cheese, banana and cinnamon, poultry (either milled chicken meat or smoked turkey breast) and catupiry, and chocolate are available. Traditionally olive oil is poured over the pizza, but in some regions people enjoy ketchup, mustard and even mayonnaise on pizza – on Rio de Janeiro, for instance, a server might be surprised if someone asks for olive oil instead of ketchup, more traditional regionally.[13]

- Brazil nut cake is a cake in Brazilian cuisine that is common and popular in the Amazon region of Brazil, Bolivia and Peru[14]

- Broa, corn bread with fennel.

Drinks

- Cachaça is Brazil's native liquor, distilled from sugar cane, and it is the main ingredient in the national drink, the Caipirinha. Other drinks include mate tea, chimarrão and tereré (both made up of yerba maté), coffee, fruit juice, beer (mainly Pilsen variety), rum, guaraná and batidas. Guaraná is a caffeinated soft drink made from guaraná seeds and batida is a type of fruit punch.[1]

- Brazilian Cachaça

Caipirinha, a national drink

Caipirinha, a national drink

Typical and popular desserts

Brazil has a variety of candies such as brigadeiros (chocolate fudge balls), cocada (a coconut sweet), beijinhos (coconut truffles and clove) and romeu e julieta (cheese with a guava jam known as goiabada). Peanuts are used to make paçoca, rapadura and pé-de-moleque. Local common fruits like açaí, cupuaçu, mango, papaya, cocoa, cashew, guava, orange, passionfruit, pineapple, and hog plum are turned in juices and used to make chocolates, popsicles and ice cream.[15]

Typical cakes (Bolos)

- Nega maluca (chocolate cake with chocolate cover and chocolate sprinkles)

- Pão de mel (honey cake, somewhat resembling gingerbread, usually covered with melted chocolate)

- Bolo de rolo (roll cake, a thin mass wrapped with melted guava)

- Bolo de cenoura (carrot cake with chocolate cover made with butter and cocoa)

- Bolo prestígio (chocolate cake with a coconut and milk cream filling, covered with brigadeiro)

- Bolo de fubá (corn flour cake)

- Bolo de milho (Brazilian-style corn cake)

- Bolo de maracujá (passion fruit cake)

- Bolo de mandioca (cassava cake)

- Bolo de queijo (literally "cheese cake")

- Bolo de laranja (orange cake)

- Bolo de banana (banana cake spread with cinnamon)

Other popular and traditional desserts

- Fig, papaya, mango, orange, citron, pear, peach, pumpkin, sweet potato (among others) sweets and preserves, often eaten with solid fresh cheese or doce de leite.

- Quindim (egg custard with coconut)[1]

- Brigadeiro (a Brazilian chocolate candy)

- Biscoitos de maizena (cornstarch cookies)

- Beijinho (coconut "truffles" with clove)

- Cajuzinho (peanut and cashew "truffles")

- Cocada (coconut sweet)

- Olho-de-sogra

- Pudim de pão (literally "bread pudding", a pie made with bread "from yesterday" immersed in milk instead of flour (plus the other typical pie ingredients like eggs, sugar etc.) with dried orange slices and clove)

- Manjar branco (coconut pudding with caramel cover and dried plums)

- Doce de leite

- Arroz-doce (rice pudding)

- Canjica (similar to rice pudding, but made with white corn)

- Romeu e Julieta: goiabada (guava cheese) with white cheese (most often Minas cheese or requeijão)

- Torta de Limão (literally "Lime Pie", a shortcrust pastry with creamy lime-flavored filling)

- Pé-de-moleque (made with peanuts and sugar caramel)

- Paçoca (similar to Spanish polvorones, but made with peanuts instead of almonds and without addition of fats)

- Pudim de leite (condensed milk-based crème caramel, of French origin)

- Brigadeirão (a pudim de leite with chocolate or a chocolate cake)

- Rapadura

- Doce de banana (different types of banana sweets, solid or creamy)

- Maria-mole

- Pamonha (a traditional Brazilian food made from fresh corn and milk wrapped in corn husks and boiled). It can be savoury or sweet.

- Papo-de-anjo

- "Açaí na tigela" (usually consists of an açaí (Brazilian fruit) mixture with bananas and cereal or strawberries and cereal (usually granola or muslix))

- Avocado cream (avocado, lime and confectionery sugar; blended and chilled)[1]

Daily meals

- Breakfast,¹ the café-da-manhã (literally, "morning coffee"): Every region has its own typical breakfast. It usually consists of a light meal, and it is not uncommon to have only a fruit or slice of bread and a cup of coffee. Traditional items include tropical fruits, typical cakes, crackers, bread, butter, cold cuts, cheese, requeijão, honey, jam, doce de leite, coffee (usually sweetened and with milk), juice, [[chocolate milk], or tea.

- Elevenses or brunch,² the lanche-da-manhã (literally, "morning snack"): Usually had between 9 and 11 am, consists of similar items as people have for breakfast.

- Midday dinner or lunch,¹ the almoço: This is usually the biggest meal and the most common times range from 11 am to 2 pm. Traditionally, people will go back to their houses to have lunch with their families, although nowadays that is not possible for most people, in which case it is common to have lunch in groups at restaurants or cafeterias. Rice is a staple of the Brazilian diet, albeit it is not uncommon to eat pasta instead. It is usually eaten together with beans and accompanied by salad, protein (most commonly red meat or chicken) and a side dish, such as polenta, potatoes, corn, etc...

- Tea,² the lanche-da-tarde or café-da-tarde (literally "afternoon snack" or "afternoon coffee"): It is a meal had between lunch and dinner, and basically everything people eat in the breakfast, they also eat in the afternoon snack. Nevertheless, fruits are less common.

- Night dinner or supper,¹ the jantar: For most Brazilians, jantar is a light affair, while others dine at night. Sandwiches, soups, salads, pasta, hamburgers or hot-dogs, pizza or repeating midday dinner foods are the most common dishes.

- Late supper,² the ceia: Brazilians eat soups, salads, pasta and what would be eaten at the elevenses if their jantar was a light one early at the evening and it is late at night or dawn. It is associated with Christmas and New Year's Eve.

¹ Main meals, that are served nearly everywhere, and are eaten in nearly all households above poverty line.

² Secondary meals. People usually have a meal at the tea time, while elevenses and late suppers depend in peculiarities on one's daily routine or certain diets.

Restaurant styles

A simple and usually inexpensive option, which is also advisable for vegetarians, is comida a quilo or comida por quilo restaurants (literally "food by kilo value"), a buffet where food is paid for by weight. Another common style is the all-you-can-eat restaurant where customers pay a prix fixe. In both types (known collectively as "self-services"), customers usually assemble the dishes of their choice from a large buffet.

Rodízio is a common style of service, in which a prix fixe is paid, and servers circulate with food. This is common in churrascarias, pizzerias and sushi (Japanese cuisine) restaurants, resulting in an all-you-can-eat meat barbecue and pizzas of varied flavours, usually one slice being served at the time.

The regular restaurant where there is a specific price for each meal is called "restaurante à la carte".

Vegetarian

Although many traditional dishes are prepared with meat or fish, it is not difficult to live on vegetarian food as well, at least in the mid-sized and larger cities of Brazil. There is a rich supply of all kinds of fruits and vegetables, and on city streets one can find cheese buns (pão de queijo); in some cities even the version made of soy.

In the 2000s, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre have gained several vegetarian and vegan restaurants.[16] However outside big metropolises, vegetarianism is not very common in the country. Not every restaurant will provide vegetarian dishes and some seemingly vegetarian meals may turn out to include unwanted ingredients, for instance, using lard for cooking beans. Commonly "meat" is understood to mean "red meat," so some people might assume a vegetarian eats fish and chicken. Comida por quilo and all-you-can eat restaurants prepare a wide range of fresh dishes. Diners can more easily find food in such restaurants that satisfies dietary restrictions.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Brittin, Helen (2011). The Food and Culture Around the World Handbook. Boston: Prentice Hall. pp. 20–21.

- ↑ "Way of Life". Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ↑ Burns, E. Bradford (1993). A History of Brazil. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 38. ISBN 0231079559.

- ↑ (in Portuguese) One century of Japanese immigration to Brazil – News –Japanese immigrants helped a 'revolution' in Brazilian agriculture

- ↑ (in Portuguese) One century of Japanese immigration to Brazil – News – Immigrants made a city in São Paulo in a great egg producer

- ↑ Roger, "Feijoada: The Brazilian national dish Archived 2009-11-29 at the Wayback Machine." braziltravelguide.com.

- ↑ Cascudo, Luis da Câmara. História da Alimentação no Brasil. São Paulo/Belo Horizonte: Editora USP/Itatiaia, 1983.

- ↑ "A feijoada não é invenção brasileira" (in Portuguese). Superinteressante. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "O Carapuceiro (jornal)" (in Portuguese). Fundaj. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ Blazes, Marian. "Brazilian Black-Eyed Pea and Shrimp Fritters – Acarajé". About.com. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ↑ Somwaru, A.; Valdes, C. (2004). Brazil's Beef Production and Its Efficiency : A Comparative Study of Scale Economies – 1–19.

- ↑ Sumayao, Marco. "What Is a Churrascaria?". WiseGeek. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- ↑ (in Portuguese) Culinary blog

- ↑ Castella, K. (2012). A World of Cake. Storey Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-60342-446-2.

- ↑ Freyre, Gilberto. Açúcar. Uma Sociologia do Doce, com Receitas de Bolos e Doces do Nordeste do Brasil. São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1997.

- ↑ "Vegetarian Restaurants in Brazil". Retrieved 2011-05-30.

External links

![]() Media related to Cuisine of Brazil at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cuisine of Brazil at Wikimedia Commons