Branched-chain amino acid

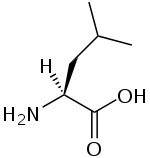

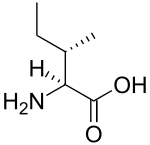

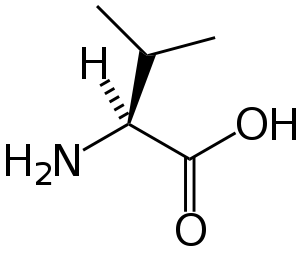

A branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) is an amino acid having aliphatic side-chains with a branch (a central carbon atom bound to three or more carbon atoms). Among the proteinogenic amino acids, there are three BCAAs: leucine, isoleucine and valine.[1] Non-proteinogenic BCAAs include 2-aminoisobutyric acid.

The three proteinogenic BCAAs are among the nine essential amino acids for humans, accounting for 35% of the essential amino acids in muscle proteins and 40% of the preformed amino acids required by mammals.[2] Synthesis for BCAAs occurs in all locations of plants, within the plastids of the cell, as determined by presence of mRNAs which encode for enzymes in the metabolic pathway.[3]

BCAAs provide several metabolic and physiologic roles. Metabolically, BCAAs promote protein synthesis and turnover, signaling pathways, and metabolism of glucose.[4][5] Oxidation of BCAAs may increase fatty acid oxidation and play a role in obesity. Physiologically, BCAAs take on roles in the immune system and in brain function. BCAAs are broken down effectively by dehydrogenase and decarboxylase enzymes expressed by immune cells, and are required for lymphocyte growth and proliferation and cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity.[4] Lastly, BCAAs share the same transport protein into the brain with aromatic amino acids (Trp, Tyr, and Phe). Once in the brain BCAAs may have a role in protein synthesis, synthesis of neurotransmitters, and production of energy.[4]

Requirements

The Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) of the U.S. Institute of Medicine set Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for essential amino acids in 2002. For leucine, for adults 19 years and older, 42 mg/kg body weight/day; for isoleucine 19 mg/kg body weight/day; for valine 4 mg/kg body weight/day.[6] For a 70 kg (154 lb) person this equates to 2.9, 1.3 and 0.3 g/day. Diets that meet or exceed the RDA for total protein (0.8 g/kg/day; 56 grams for a 70 kg person), meet or exceed the RDAs for branched-chain amino acids.

Research

Dietary BCAA supplementation has been used clinically to aid in the recovery of burn victims. However, a 2006 paper suggests that the concept of nutrition supplemented with all BCAAs for burns, trauma, and sepsis should be abandoned for a more promising leucine-only-supplemented nutrition that requires further evaluation. [7]

Dietary BCAAs have been used in an attempt to treat some cases of hepatic encephalopathy.[8] They can have the effect of alleviating symptoms, but there is no evidence they benefit mortality rates, nutrition, or overall quality of life.[9]

Certain studies suggested a possible link between a high incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) among professional American football players and Italian soccer players, and certain sports supplements including BCAAs.[10] In mouse studies, BCAAs were shown to cause cell hyper-excitability resembling that usually observed in ALS patients. The proposed underlying mechanism is that cell hyper-excitability results in increased calcium absorption by the cell and thus brings about cell death, specifically of neuronal cells which have particularly low calcium buffering capabilities.[10] Yet any link between BCAAs and ALS remains to be fully established. While BCAAs can induce a hyperexcitability similar to the one observed in mice with ALS, current work does not show if a BCAA-enriched diet, given over a prolonged period, actually induces ALS-like symptoms.[10]

Blood levels of the BCAAs are elevated in obese, insulin resistant humans and in mouse and rat models of diet-induced diabetes, suggesting the possibility that BCAAs contribute to the pathogenesis of obesity and diabetes.[11][12] BCAA-restricted diets improve glucose tolerance and promote leanness in mice, and promotes insulin sensitivity in obese rats.[13][14]

Synthesis

Five enzymes play a major role in the parallel synthesis pathways for isoleucine, valine, and leucine: threonine dehydrogenase, acetohydroxyacid synthase, ketoacid reductoisomerase, dihydroxyacid dehygrogenase and aminotransferase.[3] Threonine dehydrogenase catalyzes the deamination and dehydration of threonine to 2-ketobutyrate and ammonia. Isoleucine forms a negative feedback loop with threonine dehydrogenase. Acetohydroxyacid synthase is the first enzyme for the parallel pathway performing condensation reaction in both steps – condensation of pyruvate to acetoacetate in the valine pathway and condensation of pyruvate and 2-ketobutyrate to form acetohydroxybtylrate in the isoleucine pathway. Next ketoacid reductisomerase reduces the acetohydroxy acids from the previous step to yield dihydroxyacids in both the valine and isoleucine pathways. Dihydroxyacid dehygrogenase converts the dihyroxyacids in the next step. The final step in the parallel pathway is conducted by amino transferase, which yields the final products of valine and isoleucine.[3] A series of four more enzymes – isopropylmalate synthase, isopropylmalate isomerase, isopropylmalate dehydrogenase, and aminotransferase – are necessary for the formation of leucine from 2-oxolsovalerate.[3]

Degradation

Degradation of branched-chain amino acids involves the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex (BCKDH). A deficiency of this complex leads to a buildup of the branched-chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) and their toxic by-products in the blood and urine, giving the condition the name maple syrup urine disease.

The BCKDH complex converts branched-chain amino acids into acyl-CoA derivatives, which after subsequent reactions are converted either into acetyl-CoA or succinyl-CoA that enter the citric acid cycle.[15]

Enzymes involved are branched chain aminotransferase and 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate dehydrogenase.

Cell signaling

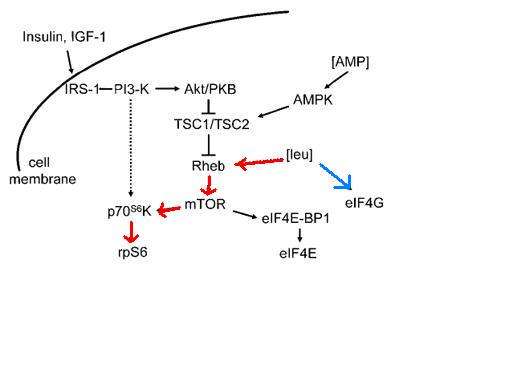

While most amino acids are oxidized in the liver, BCAAs are primarily oxidized in the skeletal muscle and other peripheral tissues.[4] The effects of BCAA administration on muscle growth in rat diaphragm was tested, and concluded that not only does a mixture of BCAAs alone have the same effect on growth as a complete mixture of amino acids, but an amino acid mixture with all but BCAAs has no effect on rat diaphragm muscle growth.[16] Administration of either isoleucine or valine alone had no effect on muscle growth, although administration of leucine alone appears to be nearly as effective as the complete mixture of BCAAs. Leucine indirectly activates p70 S6 kinase as well as stimulates assembly of the eIF4F complex, which are essential for mRNA binding in translational initiation.[16] P70 S6 kinase is part of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTOR) signaling pathway, and has been shown to allow adaptive hypertrophy and recovery of rat muscle.[17] At rest protein infusion stimulates protein synthesis 30 minutes after start of infusion, and protein synthesis stays elevated for another 90 minutes.[18] Infusion of leucine at rest produces a six hour stimulatory effect and increased protein synthesis by phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase in skeletal muscles.[18] Following resistance exercise, without BCAA administration, a resistance exercise session does not affect mTOR phosphorylation and even produces a decrease in Akt phosphorylation. Some phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase was discovered. When BCAAs were administered following a training session, sufficient phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase and S6 indicated activation of the signaling cascade.[18]

Role in diabetes mellitus type 2

In addition to cell signaling, the mTOR pathway also plays a role in beta cell growth leading to insulin secretion.[19] High glucose in the blood begins the process of the mTOR signaling pathway, which leucine plays an indirect role.[17][20] The combination of glucose, leucine, and other activators cause mTOR to start signaling for the proliferation of beta cells and the secretion of insulin. Higher concentrations of leucine cause hyperactivity in the mTOR pathway, and S6 kinase is activated leading to inhibition of insulin receptor substrate through serine phosphorylation.[19][20] In the cell the increased activity of mTOR complex causes eventual inability of beta cells to release insulin and an inhibitory effect on S6 kinase leading to insulin resistance in the cells, contributing to development of type 2 diabetes.[19]

Both humans and rats were tested for prevalence of BCAA signatures leading to insulin resistance. Human subjects’ body mass index was compared to concentration of BCAAs in their diet, as well as insulin resistance level. It was determined that subjects considered obese had higher metabolic signatures of BCAAs and higher resistance to insulin than those lean individuals with a lower body mass index.[12] In addition rats fed a diet high in BCAAs had increased rates of insulin resistance and impaired phosphorylation of enzymes within their muscles.[12]

Metformin is able to activate AMP kinase which phosphorylates proteins involved in the mTOR pathway, as well as leads to the progression of mTOR complex from its inactive state to its active state.[19] It is suggested that metformin acts as a competitive inhibitor to the amino acid leucine in the mTOR pathway.

See also

References

- ↑ Sowers, Strakie. "A Primer On Branched Chain Amino Acids" (PDF). Huntington College of Health Sciences. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Shimomura Y, Murakami T, Naoya Nakai N, Nagasaki M, Harris RA (2004). "Exercise Promotes BCAA Catabolism: Effects of BCAA Supplementation on Skeletal Muscle during Exercise". J. Nutr. 134 (6): 1583S–1587S. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Singh, Bijay (1995). "Biosynthesis of Branched Chain Amino Acids: From Test Tube to Field". The Plant Cell. 7: 935–944. doi:10.1105/tpc.7.7.935.

- 1 2 3 4 Monirujjaman, Md. (2014). "Metabolic and Physiological Roles of Branched-Chain Amino Acids". Advances in Molecular Biology. 2014: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2014/364976. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ Babchia, Narjes (2010). "The PI3K/Akt and mTOR/P70S6K Signaling Pathways in Human Uveal Melanoma Cells: Interaction with B-Raf/ERK". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 51: 421–429. doi:10.1167/iovs.09-3974. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (2002). "Protein and Amino Acids". Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrates, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 589–768.

- ↑ De Bandt JP; Cynober L (2006). "Therapeutic use of branched-chain amino acids in burn, trauma, and sepsis". J. Nutr. 1 Suppl. 136 (30): 8S–13S. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Chadalavada R, Sappati Biyyani RS, Maxwell J, Mullen K (2010). "Nutrition in hepatic encephalopathy". Nutr Clin Pract. 25 (3): 257–64. doi:10.1177/0884533610368712.

- ↑ Gluud, Lise Lotte; Dam, Gitte; Les, Iñigo; Córdoba, Juan; Marchesini, Giulio; Borre, Mette; Aagaard, Niels Kristian; Vilstrup, Hendrik (2015-09-17). "Branched-chain amino acids for people with hepatic encephalopathy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD001939. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 26377410. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001939.pub3.

- 1 2 3 Manuel, Marin; Heckman, C.J. (2011). "Stronger is not always better: Could a bodybuilding dietary supplement lead to ALS?". Experimental Neurology. 228 (1): 5–8. ISSN 0014-4886. PMC 3049458

. PMID 21167830. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.12.007.

. PMID 21167830. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.12.007. - ↑ Lynch, Christopher J.; Adams, Sean H. (2014-12-01). "Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 10 (12): 723–736. ISSN 1759-5037. PMC 4424797

. PMID 25287287. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.171.

. PMID 25287287. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.171. - 1 2 3 Newgard, Christopher B.; An, Jie; Bain, James R.; Muehlbauer, Michael J.; Stevens, Robert D.; Lien, Lillian F.; Haqq, Andrea M.; Shah, Svati H.; Arlotto, Michelle (2009-04-01). "A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance". Cell Metabolism. 9 (4): 311–326. ISSN 1932-7420. PMC 3640280

. PMID 19356713. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.002.

. PMID 19356713. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.002. - ↑ Fontana, Luigi; Cummings, Nicole E.; Arriola Apelo, Sebastian I.; Neuman, Joshua C.; Kasza, Ildiko; Schmidt, Brian A.; Cava, Edda; Spelta, Francesco; Tosti, Valeria (2016-06-21). "Decreased Consumption of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Improves Metabolic Health". Cell Reports. 16: 520–30. ISSN 2211-1247. PMC 4947548

. PMID 27346343. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.092.

. PMID 27346343. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.092. - ↑ White, Phillip J.; Lapworth, Amanda L.; An, Jie; Wang, Liping; McGarrah, Robert W.; Stevens, Robert D.; Ilkayeva, Olga; George, Tabitha; Muehlbauer, Michael J. "Branched-chain amino acid restriction in Zucker-fatty rats improves muscle insulin sensitivity by enhancing efficiency of fatty acid oxidation and acyl-glycine export". Molecular Metabolism. 5 (7): 538–551. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2016.04.006.

- ↑ Sears DD, Hsiao G, Hsiao A, Yu JG, Courtney CH, Ofrecio JM, Chapman J, Subramaniam S (2009). "Mechanisms of human insulin resistance and thiazolidinedione-mediated insulin sensitization". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106 (44): 18745–18750. PMC 2763882

. PMID 19841271. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903032106. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

. PMID 19841271. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903032106. Retrieved 22 March 2011. - 1 2 Kimball, Scot (2006). "Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms through which Branched-Chain Amino Acids Mediate Translational Control of Protein Synthesis". The Journal of Nutrition. 136: 2275–2315. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- 1 2 Bodine, Sue (2001). "Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo". Nature Cell Biology. 3: 1014–1019. PMID 11715023. doi:10.1038/ncb1101-1014. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Blomstrand, Eva (2006). "Branched-Chain Amino Acids Activate Key Enzymes in Protein Synthesis after Physical Exercise". The Journal of Nutrition. 136: 2695–2735. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Melnik, Bodo (2012). "Leucine signaling in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and obesity". World Journal of Diabetes. 3: 38–53. PMC 3310004

. PMID 22442749. doi:10.4239/WJD.v3.i3.38. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

. PMID 22442749. doi:10.4239/WJD.v3.i3.38. Retrieved 26 November 2016. - 1 2 Balcazar Morales, Norman (2012). "Role of AKT/mTORC1 pathway in pancreatic β-cell proliferation.". Colombia Medica. 43. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

External links

- Branched-chain amino acids at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- branched-chain amino acid degradation pathway

.svg.png)