Bradley Branch

| Bradley Branch | |

|---|---|

|

Lock No. 1 lies beneath the Midland Metro | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 0.6 miles (0.97 km) |

| Locks | 9 |

| Status | Filled in |

| History | |

| Date completed | 1849 |

| Date closed | 1950s |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Wednesbury Oak |

| End point | Moorcroft Junction, Moxley |

| Branch of | Birmingham Canal Navigations |

| Bradley Branch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Bradley Branch or Bradley Locks Branch was a short canal of the Birmingham Canal Navigations in the West Midlands, England. It is now disused and largely dry.

History

The area around Bradley and Wednesbury was occupied by coal mines and ironstone mines, and the ironmaster John Wilkinson built a furnace and ironworks near Bradley.[1] The Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) Old Main Line wound its way through the area in a circuitous fashion, following the 473-foot (144 m) contour. It had been authorised by Act of Parliament on 28 February 1768, and was opened for traffic between Wolverhampton and the Worcester and Birmingham Canal at Gas Street Basin on 21 September 1772.[2] A little further to the north, the Broadwaters Canal was built by the Birmingham & Birmingham & Fazeley Canal Company, an amalgamation of two rival concerns once an Act of Parliament had been obtained. This descended from the Birmingham main line through the eight Ryder's Green locks,[3] and followed the 408-foot (124 m) contour.[4] Once the Broadwaters Canal was extended to reach Walsall Town Basin in 1799, it became known as the Walsall Canal.

Several branches were built from the Broadwaters Canal to serve the growing coal-field through which it ran. Just to the south of Bradley was the Gospel Oak colliery, and a branch to this had been authorised by the 1783 Act, but work did not start until 1791, and the intention to build some locks at the far end was abandoned when it was decided to build the Bradley Hall Extension instead. This was not specifically authorised by the enabling Act, but was covered by the general powers that the Act contained. Following lengthy discussion, the decision to proceed was made in November 1794. The extension would leave the Broadwaters Canal at Moorcroft Junction, and would rise through three locks to reach Bradley Hall colliery. The cost of the work was estimated to be £1,383, just £45 more than a level canal. The mines were responsible for supplying the water to operate the locks, and the owners were told that the locks were a replacement for those not built on the Gospel Oak branch. Despite these statements, the company then entered into arbitration to ensure that the colliery companies could not make any claims against the canal company because of the change of plan. The branch opened in 1796, and the arbitration was completed two years later.[5][6]

The BCN Old Main Line became the Wednesbury Oak Loop when it was bypassed in the 1830s by a straighter route, originally planned as a deep cutting, but which incorporated the Coseley Tunnel, construction of which was authorised in 1835. The new line and tunnel were opened on 6 November 1837.[7] The Loop was itself shortened at some point, when the Rotton Brunt Line was built, which cut across a large meander.[8] The Wyrley and Essington Canal merged with the Birmingham Canal Navigations in 1840, and links between the two canal systems included the Walsall Extension Canal, which ran northwards from Walsall to meet the Wyrley and Essington at Birchills Junction.[9] A private canal, to Bradley Marr works, left the Wednesbury Oak Loop and descended through a staircase of two locks, although it did not reach either Bradley Colliery or Wilkinson's furnace at Lower Bradley.[10][11] With the Walsall Canal now providing a link to the south or the north, six locks were built in a straight line from the Rotton Brunt Line to the Bradley Hall line, which was straightened and its three locks rebuilt.[10] It was opened in 1849, becoming known as the Bradley Branch or Bradley Locks Branch,[12] and closed in the 1950s.[13]

When the canal was built, it was made quite wide, and the locks were all constructed on the northern side of the canal, rather than centrally to the channel, as most locks built previously on the BCN had been. This was probably to make the task of duplicating them easier, if this became necessary. This arrangement created a large lagoon on the southern side of the lock, at the end of which a simple cascade weir allowed surplus water to flow into the next pound. The lagoons increased the volume of water in the short pounds. The locks were built with a single gate at the top and at the bottom, whereas most locks built previously on the BCN had double gates at the bottom end of the lock.[14]

After closure, the top seven locks were filled in and the area was landscaped. It is thought that the locks and the stone walls which formed the margins of the canal are largely complete below the landscaping. The bottom two locks were partially restored using a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, and were then filled in to protect the brickwork from damage, with a view to full restoration at some time in the future. Between the bottom lock and Moorcroft Junction, the canal is level with the Walsall Canal and so is still in water, although it is heavily overgrown.[15]

Restoration Proposals

At some time prior to 2008, the Birmingham Canal Navigations Society suggested that the route could be restored, since the only structure which obstructed such a plan was the bridge at the end of the navigable section of the Wednesbury Oak Branch, and it would open up some additional circular cruising routes.[16]

In November 2013, following discussions with other interested parties, the West Midlands Waterway Partnership agreed to seek funding for a detailed feasibility study into restoration of the Bradley Canal.[17] The report was funded by the Canal & River Trust, the Inland Waterways Association, the Birmingham and Black Country Wildlife Trust, through their Nature Improvement Area Fund, and the Birmingham Canal Navigations Society, with support from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), the Environment Agency, the Forestry Commission and Natural England. The feasibility study was carried out by the consultants Moss Naylor Young.[18] In late 2015 the study found the restoration to be feasible.[19]

The aims of the restoration include the creation of a through route from the Wolverhampton Level of the Birmingham Canal main line to the Walsall Canal and the Tame Valley Canal. As well as the Bradley Branch, it includes part of the Wednesbury Oak Loop and other minor sections, and so has been labelled the 'Bradley Canal' to avoid confusion. The section affected is some 1.5 miles (2.4 km) long, and includes the nine locks of the Bradley Branch. While there are two existing routes between the ends of the Bradley Canal, that via Tipton is 9 miles (14 km) long and the route via Wolverhampton is 17 miles (27 km). The re-opened route would thus provide a much more direct link.[20]

The restored section would start near the Bradley Workshops of the Canal and River Trust at the end of the Wednesbury Oak Loop, where most of the lockgates for narrow canals are made. The only major obstacle is the road bridge carrying Bradley Lane over the canal near the workshops, which has been lowered. This would require re-alignment of the canal or the road. The rest of the route is free from development, and is protected by local planning agreements. The restoration route continues along the filled in Wednesbury Oak Loop, and along part of the Rotten Brunt line, which cut off a loop in the Wednesbury Oak Loop. It then follows the line of the Bradley Arm, descending through nine locks to reach the Walsall Canal, the top seven of which are filled in.[20]

The idea of restoring the canal was originally put forwards by the Birmingham and Black Country Wildlife Trust, which suggested it to Moss Naylor Young. They believe that the project will deliver enhancements for wildlife and to habitat, will result in some urban regeneration, and will be beneficial for recreation, heritage restoration and general education. Although their aim is not primarily concerned with navigation, they recognise that navigation will create an active and managed waterfront, which will ensure the success of the other benefits.[20] The estimated cost of the proposal is between £7 and £8 million, and the findings were announced by the Canal and River Trust on 11 November 2015. There is local support from a residents association, and as a result of the announcement, the Canal and River Trust have pledged to hold an open day at Bradley Workshops, and the Birmingham Canal Navigations Society stated that their annual spring cruise on 2 April 2016 would include the navigable section of the Wednesbury Oak Loop up to Bradley Workshops.[21]

Route

The canal left the Walsall Canal at Moorcroft Junction. As the towpath for the Walsall Canal was on the western bank, there was a towpath bridge immediately to the west of the junction. To the south of the canal was a sand pit, already marked "old" in 1890, and a chemical works, while to the north was Moorcroft Old Colliery. The southern site is now occupied by industrial units, while much of the colliery site has become Moorcroft Wood. The south-western corner was occupied by an isolation hospital in 1937, and the north-western edge is now occupied by Moorcroft Wood Primary School. There was a small basin to the south of the canal, just before the first lock was reached. Another basin turned off to the north after the lock. The Great Western Railway crossed immediately after the lock.[22]

A further basin on the north bank served Tank Foundry in 1890, but by 1937, the works had expanded and the basin had been closed. The whole complex was labelled Bradley Boiler and Engineering Works in 1937, and straddled the road, called Oak Road in 1890, but later renamed Great Bridge Road, which is still its modern name. The road crossed the canal at Bradley Bridge, below the second lock and a triangular basin on the south bank, which served a colliery. To the south was a large expanse of workings, labelled Willingsworth Collieries, but already disused in 1890. The third lock was immediately west of the road bridge, and another large basin serving the engineering works was located just above it.[22]

To the north of the next section lay Bradley Colliery. Pits 1 and 2 were close to the canal and were served by a basin. A tramway ran from the basin to pits 3 and 4 in 1903. To the south was a long basin, which left the main line opposite the north basin. It ran to some coal shafts. Housing had been built along its eastern edge by 1938, with the construction of Myrtle Terrace, and by 1967, over half of it had been filled in, and the far end was occupied by houses on Bartlett Close, although the middle section had been used to lengthen the gardens on Myrtle Terrace. Four more locks followed, after which there was a basin on the south bank which served the Wednesbury Oak Iron Works. A network of canals at a higher level, which joined the Wednesbury Oak Loop also served the area, but had been filled in by 1919, when a network of railway sidings served the adjacent Wednesbury Oak Furnaces. The furnaces and sidings had all disappeared by 1937. The final two locks raised the level to the Wolverhampton Level of the Wednesbury Oak Loop. The section where it joined was a straight cut, made to bypass a much longer loop, which broadly followed the boundary of the Weddell Wynd Community Woodland.[22]

One feature of the canal which is obvious from the maps concerns the locks and their associated lagoons. Locks 2 and 4 to 8 all have a central island in the middle of a wide canal, with a lock on the north side, and a large lagoon on the south side, which is labelled "overflow" at the downstream end where the casecade weir was. There is no evidence on the maps for a similar structure at locks 1, 3 or 9. Locks 1 and 3 both had additional basins above them, and lock 9 drew its water from the Rotton Brunt Line and the Wednesbury Oak Loop.[22]

Points of interest

Hover mouse pointer over a canal junction to see its name

|

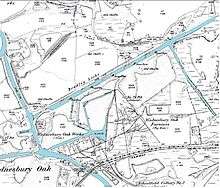

| Map of Wednesbury Oak Loop (shown in pink), an original part of James Brindley's Birmingham Canal, and its modern neighbours. The canals as they stand today are shown as solid lines. The Bradley Branch (top of map) linked the BCN Old Main Line and the Walsall Canal through nine locks. |

See also

Bibliography

- Broadbridge, S R (1974). The Birmingham Canal Navigations Vol 1 1768-1846. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-6381-2.

- Hadfield, Charles (1985). The Canals of the West Midlands. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8644-6.

- Moss, Patrick; et al. (2015). "Bradley Canal Restoration Feasibility Study" (PDF). West Midlands Waterway Partnership.

- Shill, Ray (2005). Birmingham and the Black Country's Canalside Industries. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-3262-5.

- Shill, Ray (31 May 2010). "BCN Branches and Bye ways: 1: Bradley Loop". Birmingham Canal Navigations Society.

References

- ↑ Shill 2005, p. 28.

- ↑ Hadfield 1985, pp. 64-68.

- ↑ Hadfield 1985, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ Hadfield 1985, pp. 66-67.

- ↑ Broadbridge 1974, p. 86.

- ↑ "Bradley Locks, Bradley Branch Canal". Black Country History. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ↑ Hadfield 1985, p. 88.

- ↑ Moss 2015, p. 3.

- ↑ Hadfield 1985, p. 99.

- 1 2 Shill 2010, p. 1.

- ↑ Moss 2015, p. 4.

- ↑ Hadfield 1985, pp. 318–319

- ↑ Moss 2015, p. 1.

- ↑ Moss 2015, pp. 4, 28.

- ↑ Moss 2015, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ "BCNS Gallery". Archived from the original on 23 November 2008.

- ↑ "West Midlands Waterways Partnership minutes" (PDF). Canal and River Trust. 7 November 2013. Item 5.

- ↑ Moss 2015, p. ii.

- 1 2 3 "Bradley Canal Restoration Feasibility Study". Biodiversity Action Reporting System. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Plans to Restore Bradley Arm. Waterways World. January 2016. ISSN 0309-1422.

- 1 2 3 4 Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1890/1919/1938/1967/modern.

- ↑ All coordinates: WGS84, from Google, with reference to Ordnance Survey map 1:10560 SO99SE dated 1955

Coordinates: 52°33′02″N 2°03′03″W / 52.5506°N 2.0509°W