Bowery

Route map: Google

|

Looking north from Houston Street | |

| Former name(s) | Bowery Lane (prior to 1807) |

|---|---|

| Length | 1.6 km (1.0 mi) |

| South end | Chatham Square |

| North end | East 4th Street (continues as Cooper Square) |

The Bowery /ˈbaʊəri/[1] is a street and neighborhood in the southern portion of the New York City borough of Manhattan. The street runs from Chatham Square at Park Row, Worth Street, and Mott Street in the south to Cooper Square at 4th Street in the north,[2] while the neighborhood's boundaries are roughly East 4th Street and the East Village to the north; Canal Street and Chinatown to the south; Allen Street and the Lower East Side to the east; and Little Italy to the west.[3]

In the 17th century, the road branched off Broadway north of Fort Amsterdam at the tip of Manhattan to the homestead of Peter Stuyvesant, Director-General of New Netherland. The street was known as Bowery Lane prior to 1807.[4] "Bowery" is an anglicization of the Dutch bouwerij, derived from an antiquated Dutch word for "farm", as in the 17th century the area contained many large farms.[2]

A New York City Subway station named Bowery, serving the BMT Nassau Street Line (J M Z trains), is located close to the Bowery's intersection with Delancey and Kenmare Streets. There is a tunnel under the Bowery once intended for use by proposed but never built New York City Subway services, including the Second Avenue Subway.[5][6]

History

Colonial and Federal periods

The Bowery is the oldest thoroughfare on Manhattan Island, preceding European intervention as a Lenape footpath, which spanned roughly the entire length of the island, from north to south.[7] When the Dutch settled Manhattan island, they named the path Bouwerij road—"bouwerij" being an old Dutch word for "farm"[8]—because it connected farmlands and estates on the outskirts to the heart of the city in today's Wall Street/Battery Park area.

In 1654, the Bowery’s first residents settled in the area of Chatham Square; ten freed slaves and their wives set up cabins and a cattle farm there.

Petrus Stuyvesant, the last Dutch Governor of New Amsterdam before the English took control, retired to his Bowery farm in 1667. After his death in 1672, he was buried in his private chapel. His mansion burned down in 1778 and his great-grandson sold the remaining chapel and graveyard, now the site of the Episcopal church of St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery.[9]

In her Journal of 1704–05, Sarah Kemble Knight describes the Bowery as a leisure destination for residents of New York City in December:

Their Diversions in the Winter is Riding Sleys about three or four Miles out of Town, where they have Houses of entertainment at a place called Bowery, and some go to friends Houses who handsomely treat them. [...] I believe we mett 50 or 60 slays that day—they fly with great swiftness and some are so furious that they'le turn out of the path for none except a Loaden Cart. Nor do they spare for any diversion the place affords, and sociable to a degree, they'r Tables being as free to their Naybours as to themselves.

By 1766, when John Montresor made his detailed plan of New York,[10] "Bowry Lane", which took a more north-tending track at the rope walk, was lined for the first few streets with buildings that formed a solid frontage, with market gardens behind them; when Lorenzo Da Ponte, the librettist for Mozart's Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and Così fan tutte, immigrated to New York City in 1806, he briefly ran one of the shops along the Bowery, a fruit and vegetable store. In 1766, straight lanes led away at right angles to gentlemen's seats, mostly well back from the dusty "Road to Albany and Boston", as it was labeled on Montresor's map; Nicholas Bayard's was planted as an avenue of trees. James Delancey's grand house, flanked by matching outbuildings, stood behind a forecourt facing Bowery Lane; behind it was his parterre garden, ending in an exedra, clearly delineated on the map.

.jpg)

The Bull's Head Tavern was noted for George Washington's having stopped there for refreshment before riding down to the waterfront to witness the departure of British troops in 1783. Leading to the Post Road, the main route to Boston, the Bowery rivaled Broadway as a thoroughfare; as late as 1869, when it had gained the "reputation of cheap trade, without being disreputable" it was still "the second principal street of the city".[11]

Rise of the area

As the population of New York City continued to grow, its northern boundary continue to move, and by the early 1800s the Bowery was no longer a farming area outside the city. The street gained in respectability and elegance, becoming a broad boulevard, as well-heeled and famous people moved their residences there, including Peter Cooper, the industrialist and philanthropist.[2] The Bowery began to rival Fifth Avenue as an address.[2]

When Lafayette Street was opened parallel to the Bowery in the 1820s, the Bowery Theatre was founded by rich families on the site of the Red Bull Tavern, which had been purchased by John Jacob Astor; it opened in 1826 and was the largest auditorium in North America at the time.[2] Across the way the Bowery Amphitheatre was erected in 1833, specializing in the more populist entertainments of equestrian shows and circuses. From stylish beginnings, the tone of Bowery Theatre's offerings matched the slide in the social scale of the Bowery itself.

Slide from respectability

By the time of the Civil War, the mansions and shops had given way to low-brow concert halls, brothels, German beer gardens, pawn shops, and flophouses, like the one at No.15 where the composer Stephen Foster lived in 1864.[12] Theodore Dreiser closed his tragedy Sister Carrie, set in the 1890s, with the suicide of one of the main characters in a Bowery flophouse. The Bowery, which marked the eastern border of the slum of "Five Points", had also become the turf of one of America's earliest street gangs, the nativist Bowery Boys. In the spirit of social reform, the first YMCA opened on the Bowery in 1873;[13] another notable religious and social welfare institution established during this period was the Bowery Mission, which was founded in 1880 at 36 Bowery by Reverend Albert Gleason Ruliffson. The mission has relocated along the Bowery throughout its lifetime. From 1909 to the present, the mission has remained at 227–229 Bowery.

By the 1890s, the Bowery was a center for prostitution that rivaled the Tenderloin, and for bars catering to gay men and some lesbians at various social levels, from The Slide at 157 Bleecker Street, New York's "worst dive",[14] to Columbia Hall at 5th Street, called Paresis Hall. One investigator in 1899 found six saloons and dance halls, the resorts of "degenerates" and "fairies", on the Bowery alone.[15] Gay subculture was more highly visible there and more integrated into working-class male culture than it was to become in the following generations, according to the historian of gay New York, George Chauncey.

From 1878 to 1955 the Third Avenue El ran above the Bowery, further darkening its streets, populated largely by men. "It is filled with employment agencies, cheap clothing and knickknack stores, cheap moving-picture shows, cheap lodging-houses, cheap eating-houses, cheap saloons", writers in The Century Magazine found it in 1919. "Here, too, by the thousands come sailors on shore leave,—notice the 'studios' of the tattoo artists,—and here most in evidence are the 'down and outs'".[16] Prohibition eliminated the Bowery's numerous saloons: One Mile House, the "stately old tavern... replaced by a cheap saloon"[17] at the southeast corner of Rivington Street, named for the battered milestone across the way,[18] where the politicians of the East Side had made informal arrangements for the city's governance, [19][20] was renovated for retail space in 1921, "obliterating all vestiges of its former appearance", The New York Times reported. Restaurant supply stores were among the businesses that had come to the Bowery,[21] and many remain to this day.

Pressure for a new name after World War I came to naught[21] and in the 1920s and 1930s, it was an impoverished area. From the 1940s through the 1970s, the Bowery was New York City's "Skid Row," notable for "Bowery Bums" (disaffiliated alcoholics and homeless persons).[22] Among those who wrote about Bowery personalities was New Yorker staff member Joseph Mitchell (1908–1996). Aside from cheap clothing stores that catered to the derelict and down-and-out population of men, commercial activity along the Bowery became specialized in used restaurant supplies and lighting fixtures.[2]

Revival

The vagrant population of the Bowery declined after the 1970s, in part because of the city's effort to disperse it.[2] Since the 1990s the entire Lower East Side has been reviving. As of July 2005, gentrification is contributing to ongoing change along the Bowery. In particular, the number of high-rise condominiums is growing. In 2006, AvalonBay Communities opened its first luxury apartment complex on the Bowery, which included an upscale Whole Foods Market. Avalon Bowery Place was quickly followed with the development of Avalon Bowery Place II in 2007. That same year, the SANAA-designed facility for the New Museum of Contemporary Art opened between Stanton and Prince Street.

The new development has not come without a social cost. Michael Dominic's documentary Sunshine Hotel followed the lives of residents of one of the few remaining flophouses.

The Bowery from Houston to Delancey Street serves as New York's principal market for restaurant equipment, and from Delancey to Grand for lamps.

Areas

Bowery Historic District

In October 2011, a Bowery Historic District was registered with the New York State Register of Historic Places and, because of that, automatically nominated for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. A grassroots community organization named Bowery Alliance of Neighbors (BAN) in association with the community-based housing organization called the Two Bridges Neighborhood Council led the effort for creation of the historic district. The designation means that property owners will have financial incentives to restore rather than demolish old buildings on the Bowery.[23] BAN was recognized for its preservation efforts with a Village Award[24] from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation in 2013.

The historic district runs from Chatham Square to Astor Place on both sides of the Bowery.

Little Saigon

New York's "Little Saigon", though not officially designated, exists on the Bowery between Grand Street and Hester Street.[25] New York magazine claims that while this street blends in with neighboring Chinatown, the area is filled with Vietnamese restaurants.[26]

Notable places

Amato Opera

This company, founded in 1948 by Tony Amato and his wife, Sally, found a permanent home at 319 Bowery next to the former CBGB and afforded many young singers the opportunity to hone their craft in full-length productions with a cut-down orchestration. The curtain fell on this well-established NYC opera forum on May 31, 2009, when Tony Amato retired.

Bank buildings

The Bowery Savings Bank was chartered in May 1834, when the Bowery was an upscale residential street, and grew with the rising prosperity of the city. Its 1893 headquarters building remains a Bowery landmark, as does the 1920s domed Citizens Savings Bank.[27]

Bowery Ballroom

The Bowery Ballroom is a music venue. The structure, at 6 Delancey Street, was built just before the Stock Market Crash of 1929. It stood vacant until the end of World War II, when it became a high-end retail store. The neighborhood subsequently went into decline again, and so did the caliber of businesses occupying the space.[28] In 1997 it was converted into a music venue. It has a capacity of 550 people.[29]

Directly in front of the venue's entrance is the Bowery Station (J M Z trains) of the New York City Subway.

The club serves as the namesake of at least one recording: Joan Baez's Bowery Songs album, recorded live at a concert at the Bowery Ballroom in November 2004.

Bowery Mural

The Bowery Mural is an outdoor exhibition space located on the corner of Houston Street and the Bowery, on a wall owned by Goldman Properties since 1984. Real estate developer Tony Goldman began the project with Jeffery Deitch and Deitch Projects in 2008. Goldman’s goal was to use this wall to present the top contemporary artists from around the world, with an emphasis on artists who work on the streets. Seasonal murals have appeared on the wall curated and organized in collaboration with The Hole, NYC, an art gallery in SoHo run by former Deitch Projects directors Kathy Grayson and Meghan Coleman.

The mural series was initiated from March to December 2008 with a tribute to Keith Haring’s noted 1982 Bowery mural. This was followed by a mural by the Brazilian twin-brother duo Os Gêmeos, which they dedicated to artist Dash Snow, who had recently died from a drug overdose; this was presented from July 2009 to March 2010. The next mural, by Shepard Fairey, was on exhibit from April through August 2010, and was followed by a mural by Barry McGee which celebrated the role of graffiti tagging in the history of New York City street art; it was on display from August to November 2010. This was followed by a tribute to Dash Snow by Irak, which ran from November 24–26, 2010.[30] Other artists to have murals presented include the twins How & Nosm (2012), Crash (2013), Martha Cooper (2013), Revok and POSE (2013), Swoon (2014), and Maya Hayuk (whose mural was tag-bombed several times shortly after its completion in 2014).[31][32]

Bowery Poetry

Bowery Poetry is a performance space at Bowery and Bleecker Street. It was founded in 2001 as Bowery Poetry Club (BPC), and provided a home base for established and upcoming artists. It was founded by Bob Holman, owner of the building and former Nuyorican Poets Café Poetry Slam MC (1988–1996). The BPC featured regular shows by Amiri Baraka, Anne Waldman, Taylor Mead, Taylor Mali, along with open mic, gay poets, a weekly poetry slam, and an Emily Dickinson Marathon, amongst other events. The club closed in 2012 and reopened in 2013 as a shared performance space under the name "Bowery Poetry". Bowery Arts + Science presents poetry, and Duane Park presents alternative burlesque in this space.[33]

Bowery Theatre

The Bowery Theatre was a 19th-century playhouse at 46 Bowery. It was founded in the 1820s by rich families to compete with the upscale Park Theatre. By the 1850s, the theatre came to cater to immigrant groups such as the Irish, Germans, and Chinese. It burned down four times in 17 years, and a fire in 1929 destroyed it for good.

CBGB

CBGB, a club that was opened to play country, bluegrass & blues (as the name CBGB stands for), began to book Television, Patti Smith, and the Ramones as house bands in the mid-1970s. This spawned a full-blown scene of new bands (Talking Heads, Blondie, edgy R&B-influenced Mink DeVille, rockabilly revivalist Robert Gordon, and others) performing mostly original material in a mostly raw and often loud and fast attack. The label of punk rock was applied to the scene even if not all the bands that made their early reputations at the club were punk rockers, strictly speaking, but CBGB became known as the American cradle of punk rock. CBGB closed on October 31, 2006, after a long battle by club owner Hilly Kristal to extend its lease. The space is now a John Varvatos boutique.

New Museum

In December 2007, the New Museum opened the doors of its new location at 235 Bowery, at Prince Street, continuing its focus of exhibiting emerging international artists. This new facility, designed by the Tokyo-based firm Sejima + Nishizawa/SANAA and the New York-based firm Gensler, has greatly expanded the Museum’s exhibitions and space. In March 2008, the museum's new building was named one of the architectural seven wonders by Conde Nast Traveler.[34] The museum has an ongoing Bowery Project honoring artists who lived on the Bowery with taped interviews and archived records.[35]

Notable people

- Photographer Terry Richardson lives in his studio on Bowery south of Houston Street.

- Béla Bartók lived in 350 Bowery at the corner of Great Jones Street during the 1940s.

- The writer William S. Burroughs kept an apartment at the former YMCA building at 222 Bowery, known as the Bunker, from 1974 until he moved to Lawrence, Kansas, in 1981.

- Mark Rothko, the Abstract Expressionist painter, had a studio at 222 Bowery.

- Pop artist Tom Wesselman had a studio on Bowery in the building now adjacent to the New Museum.

- The founder of the Hare Krishna Movement, A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, lived on Bowery when the movement began in America in 1966.

- Comedian, actor Jim Gaffigan lives with his wife and five children in a five-story walk-up on the Bowery.

- Punk singer Joey Ramone resided in the area, and in 2003 a part of 2nd Street near the intersection of Bowery and 2nd Street was renamed Joey Ramone Place.[36][37]

- The artist Cy Twombly lived on the third floor of 356 Bowery during the 1960s.

- Nightclub doorman and cabaret promotor Haoui Montaug lived at the corner of Bowery and East 2nd Street. He committed suicide in his apartment after inviting twenty guests for the occasion.[38][39]

- Sculptor Eva Hesse lived in her studio at 134 Bowery.

- Painter Ronnie Landfield lived at 94 Bowery.

- Painter Peter Young lived at 94 Bowery.

- Painter Michael Goldberg lived at 222 Bowery.

In popular culture

Literature

- Bowery is the setting for Stephen Crane's first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (published in 1893), about a poor family living in the neighborhood.

- New York School poet Ted Berrigan mentions the Bowery several times in his seminal work "The Sonnets".

- In Jack Kirby and Stan Lee's Fantastic Four #4 (1962), the Human Torch flees to the Bowery to lose himself "among all the other human derelicts..." In one of the Bowery's flophouses, he discovers the amnesiac 1940s-era character Namor the Sub-Mariner.[40]

- The Wild Cards series of books sets the Bowery as Jokertown, the place where the malformed go to live after the Wild Card Virus is released over New York.

- Brenda Coultas' 2003 book of poetry, A Handmade Museum, contains a section called "the Bowery Project" which documents the pre-gentrification process.

Music

- Over the years, the Bowery has been mentioned in the lyrics of a number of songs, including the Bob Dylan song "Bob Dylan's 115th Dream", from the album Bringing It All Back Home (1965): "I walked by a Guernsey cow / Who directed me down / To the Bowery slums / Where people carried signs around / Saying, 'Ban the bums.'"

- Exuma, Bahamian folk singer and then resident of New York City has a song called "The Bowery" in his 1971 album Doo Wah Nanny. It describes the place as a "skid row".

- The street has also been mentioned in songs by Broken Bells, They Might Be Giants, Willie Nile, Jim Croce, Regina Spektor, Dire Straits, Bill Callahan, Saint Etienne the Vancouver Twee pop band cub, Sonic Youth, Two Gallants, Steve Earle, Beastie Boys, Paul McDermott, Billy Joel, The Decemberists, Tom Waits, Ryan Adams, The Clash, the Ramones, Jesse Malin and The Foetus All-Nude Revue, The Lumineers, Deerhunter, Local Natives, Smog, Blood Orange, The Antlers, Lady Gaga, Kygo among others.

- Bowery is mentioned as a place where love and gin can be found in the lyrics of Stephin Merritt's song "Love is Like a Bottle of Gin" from the album 69 Love Songs.

- Rock band Bowery Electric's name was originated by Lawrence Chandler while residing in the area.

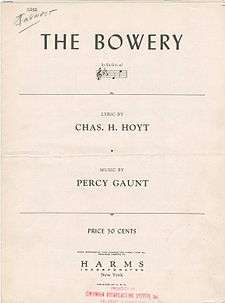

Stage

- The phrase "On the Bowery", which has since fallen into disuse, was a generic way to say one was down-and-out. It originated in the song "The Bowery" from the 1891 musical A Trip to Chinatown,[41] which included the chorus "The Bow’ry, The Bow’ry! / They say such things, / and they do strange things / on the Bow’ry"[42]

- On the Bowery, an 1894 play starring Steve Brodie, supposed Brooklyn Bridge jumper and Bowery saloonkeeper.

- In Disney's "Newsies", the showgirls featured in the song, "I Never Planned On You/ Don't Come A-Knocking" are called the Bowery Beauties.

Film and TV

- The 1925 film Little Annie Rooney takes place in the Bowery.

- The Bowery, a 1933 film about Brodie.

- The Bowery is portrayed in the 1934 Krazy Kat cartoon Bowery Daze.

- A popular B-movie series made between 1946 and 1958 featured "The Bowery Boys", led by Slip (Leo Gorcey) and Satch (Huntz Hall).

- The 1949 cartoon "Bowery Bugs" tells a fictionalized version of the Steve Brodie story, with Bugs Bunny as Brody's tormenter.

- On the Bowery, Lionel Rogosin's 1956 film, was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary.

- In the 2002 film Gangs of New York, Bowery is a mentioned territory of the Bowery Boys, a street gang of the late 19th century during the New York Draft Riots.

Art

- The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, a collection of photographs and poems by Martha Rosler.[43]

- "Come Closer: Art Around the Bowery, 1969–1989", "Drawing upon the New Museum’s Bowery Artist Tribute archive and the online archive of Marc H. Miller, 98bowery.com, this exhibition features original artwork, ephemera, and performance documentation by over fifteen artists who lived and worked on or near [the] Bowery in New York."[44]

Advertising

- In the 1960s, radio and television commercials for the Bowery Savings Bank featured a jingle with the lyrics "The Bowery, The Bowery / The Bowery pays a lot / The Bowery pays you 6% / Commercial banks in New York simply do not." The number changed according to the amount of interest available on a passbook savings account offered by the bank.

Wrestling

- Professional wrestler Raven is billed as being from the Bowery despite his being born in Philadelphia and residing in Atlanta.[45]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ http://www.dictionary.com/browse/bowery Bowery at dictionary.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jackson, Kenneth L. "Bowery" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010), The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.), New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2, p.148

- ↑ citidex.com 2006; Fodor's 1991

- ↑ Brown, 1922

- ↑ Second Avenue Subway: Completed Portions, 1970s

- ↑ Manhattan East Side Transit Alternatives (MESA)/Second Avenue Subway Summary Report

- ↑ Sanderson, Eric W. Mannahatta: A Natural History of New york City, 2009, p. 107, illus. "Lenape sites and trails", and Ch. 4 "The Lenape", passim.

- ↑ In modern Dutch, boerderij

- ↑ Fodor's 2004

- ↑ The relevant section is illustrated in Sanderson 2009, p. 41, bottom.

- ↑ Smith, Matthew Hale. Sunshine and Shadow in New York, 1869, p.214.

- ↑ Moscow, Henry (1978), The Street Book: An Encyclopedia of Manhattan's Street Names and Their Origins, New York: Hagstrom, ISBN 0823212750; A highly colored and disapproving panorama of the dissolute and lively Bowery on a Sunday is offered by Smith 1869, pp. 214–18.

- ↑ Levinson, David ed. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Homelessness, s.v. "Bowery, The".

- ↑ Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940: ch. 1 "The Bowery as haven and spectacle" (1994:32–45), p. 37

- ↑ Chauncey 1994:33.

- ↑ Frank, Mary and Carr, John Foster, "Exploring a neighborhood", The Century Magazine 98 (July 1919:378).

- ↑ Frank and Carr 1919:378; the old tavern had been the scene of at least one violent murder, in 1862 ("The Murder in the Bowery", New York Times, 4 November 1862 accessed March 14, 2010.

- ↑ The stone marked a mile from City Hall; it was still in evidence in 1909 (Frank Bergen Kelly, Historical Guide to the City of New York (City History Club of New York), 1909:97.

- ↑ "Bowery Landmark in $170,000 Lease". The New York Times. April 1, 1921. p. 32. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ↑ One Mile House by Glenn O. Coleman, 1928 (Whitney Museum of American Art) epitomizes the scene. A ghostly painted sign on the side of the building still advertises One Mile House.

- 1 2 "Business Changes Along Bowery". The New York Times. December 11, 1921. p. 125. Retrieved July 11, 2010. Today, the gentrified designation "Cooper Square" extends down the Bowery as far as 4th Street.

- ↑ Giamo, Benedict, On the Bowery: confronting homelessness in American Society (University of Iowa Press) 1989.

- ↑ Clark, Roger (October 25, 2011). "Bowery Lands Spot On State Historic Registry". NY1.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Bowery Alliance of Neighbors: 2013 Village Award Winner". GVSHP.org. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ↑ "Tiny Little Saigon in New York".

- ↑ "Bánh Mì Saigon Bakery".

- ↑ "New Bank Building; Citizens Savings Bank to Erect Monumental Structure on Bowery". The New York Times. July 2, 1922. p. 84. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ↑ "History of the Bowery Ballroom", Bowery Ballroom website (archived 2007)

- ↑ Carlson, Jen (2007-08-14). "New Venue Alert: Terminal 5". Gothamist. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ↑ "Houston Bowery Wall" on the Goldman Properties website

- ↑ "Bombed Again at the Houston/Bowery Mural Wall" on the EV Grieve website

- ↑ "Bowery Houston Mural" on the Arrested Motion website

- ↑ "Bowery Poetry". www.boweryartsandscience.org. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ↑ Associated Press (March 30, 2008). "Structures Considered Most Amazing in World". The News Leader. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ↑ Bowery Artist Tribute

- ↑ "He Had the Beat — and Now Has a Street". The Washington Post. December 7, 2003. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

Now there is Joey Ramone Place.... The sign bearing Ramone's name recently went up on the corner of 2nd Street and Bowery, near CBGB, the group's musical home.

- ↑ Gamboa, Glen (August 10, 2005). "The Fold: Battle over punk birthplace: Rock & rent". Newsday. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

Reminders of the bands who have passed through CBGB remain all around the club, from the corner of Bowery and 2nd Street—now renamed Joey Ramone Place—to the countless band names scrawled on the bathroom walls.

- ↑ Lynn Yaeger. "All Sold Out at CBGB". The Village Voice.

- ↑ New York Media, LLC (13 January 1997). New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. pp. 29–. ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Fantastic Four #4 (1962).

- ↑ On the Bowery, Steve Zeitlin and Marci Reaven, New York Folklore Society's journal Voices, Vol. 29, Fall-Winter, 2003.

- ↑ Information about the musical (Archived 2009-10-23)

- ↑ "The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems". The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems. The New Museum.

- ↑ "Come Closer: Art Around the Bowery, 1969–1989". Come Closer: Art Around the Bowery, 1969–1989. The New Museum.

- ↑ "Raven". WWE.com. WWE. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

Sources

- Fodor's flashmaps New York, 1991

- Fodor's See It New York City, 2004, ISBN 1-4000-1387-9

- Valentine's Manual of Old New York / No. 7, Ed. Henry Collins Brown, Pub. Valentine's Manual Inc. 1922

Further reading

- Bowery by Forgotten NY—images, descriptions, and history

- East Village History Project Bowery research—in-depth, lot by lot research

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bowery. |

- Bowery, from the Little Italy Neighbors Association—stories, photos, etc.

- Bowery Storefronts—photographs of Bowery stores and buildings.

- Bowery documentary

Historic district

- Map of Bowery Historic District

- Bowery Historic District nomination, National Register of Historic Places

Organizations

- Bowery Alliance, a grassroots organization

- Bowery Artist Tribute

- Lower East Side Preservation Initiative