Tuberous sclerosis

| Tuberous sclerosis complex | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms |

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), Bourneville disease |

| |

| A case of tuberous sclerosis showing facial angiofibromas in characteristic butterfly pattern | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | neurology, medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q85.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 759.5 |

| OMIM | 191100 613254 |

| DiseasesDB | 13433 |

| MedlinePlus | 000787 |

| eMedicine | neuro/386 derm/438 ped/2796 radio/723 |

| Patient UK | Tuberous sclerosis |

| MeSH | D014402 |

| GeneReviews | |

| Orphanet | 805 |

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a rare multisystem genetic disease that causes benign tumors to grow in the brain and on other vital organs such as the kidneys, heart, liver, eyes, lungs, and skin. A combination of symptoms may include seizures, intellectual disability, developmental delay, behavioral problems, skin abnormalities, and lung and kidney disease. TSC is caused by a mutation of either of two genes, TSC1 and TSC2, which code for the proteins hamartin and tuberin, respectively. These proteins act as tumor growth suppressors, agents that regulate cell proliferation and differentiation.[1]

The name, composed of the Latin tuber (swelling) and the Greek skleros (hard), refers to the pathological finding of thick, firm, and pale gyri, called "tubers", in the brains of patients post mortem. These tubers were first described by Désiré-Magloire Bourneville in 1880; the cortical manifestations may sometimes still be known by the eponym Bourneville's disease (English: /bɔərnˈviːl/) or Bourneville–Pringle disease (after Bourneville and John James Pringle). The full name of "tuberous sclerosis complex" is preferred among medical professionals and researchers today because the disease has manifestations outside of the brain.[2] Furthermore, the name reduces confusion with tuberculosis, a more well-known disease.

Signs and symptoms

The physical manifestations of TSC are due to the formation of hamartia (malformed tissue such as the cortical tubers), hamartomas (benign growths such as facial angiofibroma and subependymal nodules), and very rarely, cancerous hamartoblastomas. The effect of these on the brain leads to neurological symptoms such as seizures, intellectual disability, developmental delay, and behavioral problems. Symptoms also include trouble in school and concentration problems.

Central nervous system

About 50% of people with TSC have learning difficulties ranging from mild to significant,[3] and studies have reported that between 25% and 61% of affected individuals meet the diagnostic criteria for autism, with an even higher proportion showing features of a broader pervasive developmental disorder.[4] A 2008 study reported self-injurious behavior in 10% of people with TSC.[5] Other behaviors and disabilities, such as ADHD, aggression, behavioral outbursts, and OCD can also occur. Lower IQ is associated with more brain involvement on MRI.

Three types of brain tumours may be associated with TSC:

- Giant cell astrocytoma: (grows and blocks the cerebrospinal fluid flow, leading to dilatation of ventricles causing headache and vomiting)

- Cortical tubers: after which the disease is named

- Subependymal nodules: form in the walls of ventricles

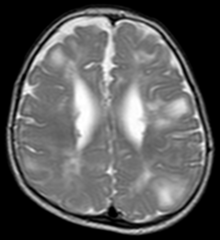

Classic intracranial manifestations of TSC include subependymal nodules and cortical/subcortical tubers.[6]

The tubers are typically triangular in configuration, with the apex pointed towards the ventricles, and are thought to represent foci of abnormal neuronal migration. The T2 signal abnormalities may subside in adulthood, but will still be visible on histopathological analysis. On magnetic resonance imaging, TSC patients can exhibit other signs consistent with abnormal neuron migration such as radial white matter tracts hyperintense on T2WI and heterotopic gray matter.

Subependymal nodules are composed of abnormal, swollen glial cells and bizarre multinucleated cells which are indeterminate for glial or neuronal origin. Interposed neural tissue is not present. These nodules have a tendency to calcify as the patient ages. A nodule that markedly enhances and enlarges over time should be considered suspicious for transformation into a subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, which typically develops in the region of the foramen of Monro, in which case it is at risk of developing an obstructive hydrocephalus.

A variable degree of ventricular enlargement is seen, either obstructive (e.g. by a subependymal nodule in the region of the foramen of Monro) or idiopathic in nature.

Kidneys

Between 60 and 80% of TSC patients have benign tumors (once thought hamartomatous, but now considered true neoplasms) of the kidneys called angiomyolipomas frequently causing hematuria. These tumors are composed of vascular (angio–), smooth muscle (–myo–), and fat (–lip-) tissue. Although benign, an angiomyolipoma larger than 4 cm is at risk for a potentially catastrophic hemorrhage either spontaneously or with minimal trauma. Angiomyolipomas are found in about one in 300 people without TSC. However, those are usually solitary, whereas in TSC they are commonly multiple and bilateral.

About 20-30% of people with TSC have renal cysts, causing few problems. However, 2% may also have autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Very rare (< 1%) problems include renal cell carcinoma and oncocytomas (benign adenomatous hamartoma).

Lungs

Patients with TSC can develop progressive replacement of the lung parenchyma with multiple cysts. This process is identical to another disease called lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). Recent genetic analysis has shown that the proliferative bronchiolar smooth muscle in TSC-related lymphangioleiomyomatosis is monoclonal metastasis from a coexisting renal angiomyolipoma. Cases of TSC-related lymphangioleiomyomatosis recurring following lung transplant have been reported.[7]

Heart

Rhabdomyomas are benign tumors of striated muscle. A cardiac rhabdomyoma can be discovered using echocardiography in around 50% of people with TSC. However, the incidence in the newborn may be as high as 90% and in adults as low as 20%. These tumors grow during the second half of pregnancy and regress after birth. Many disappear entirely; alternatively, the tumor size remains constant as the heart grows, which has much the same effect.

Problems due to rhabdomyomas include obstruction, arrhythmia, and a murmur. Such complications occur almost exclusively during pregnancy or within the child's first year. Prenatal ultrasound, performed by an obstetric sonographer specializing in cardiology, can detect a rhabdomyoma after 20 weeks. This rare tumour is a strong indicator of TSC in the child, especially if a family history of TSC exists.

Skin

Some form of dermatological sign is present in 96% of individuals with TSC. Most cause no problems, but are helpful in diagnosis. Some cases may cause disfigurement, necessitating treatment. The most common skin abnormalities include:

- Facial angiofibromas ("adenoma sebaceum"): A rash of reddish spots or bumps, which appears on the nose and cheeks in a butterfly distribution, they consist of blood vessels and fibrous tissue. This potentially socially embarrassing rash starts to appear during childhood and can be removed using dermabrasion or laser treatment.

- Periungual fibromas: Also known as Koenen's tumors, these are small fleshy tumors that grow around and under the toenails or fingernails and may need to be surgically removed if they enlarge or cause bleeding. These are very rare in childhood, but common by middle age. They are generally more common on toes than on fingers, develop at 15–29 years, and are more common in women than in men. They can be induced by nail-bed trauma.

- Hypomelanic macules ("ash leaf spots"): White or lighter patches of skin, these may appear anywhere on the body and are caused by a lack of melanin. They are usually the only visible sign of TSC at birth. In fair-skinned individuals, a Wood's lamp (ultraviolet light) may be required to see them.

- Forehead plaques: Raised, discolored areas on the forehead

- Shagreen patches: Areas of thick leathery skin that are dimpled like an orange peel, and pigmented, they are usually found on the lower back or nape of the neck, or scattered across the trunk or thighs. The frequency of these lesions rises with age.

- Other skin features are not unique to individuals with TSC, including molluscum fibrosum or skin tags, which typically occur across the back of the neck and shoulders, café au lait spots or flat brown marks, and poliosis, a tuft or patch of white hair on the scalp or eyelids.

Eyes

Retinal lesions, called astrocytic hamartomas (or "phakomas"), which appear as a greyish or yellowish-white lesion in the back of the globe on the ophthalmic examination. Astrocytic hamartomas can calcify, and they are in the differential diagnosis of a calcified globe mass on a CT scan.

Nonretinal lesions associated with TSC include:

- Coloboma

- Angiofibromas of the eyelids

- Papilledema (related to hydrocephalus)

Pancreas

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours have been described in rare cases of TSC.[8]

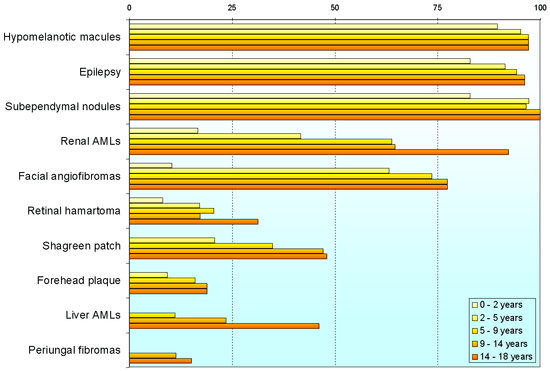

Variability

Individuals with TSC may experience none or all of the clinical signs discussed above. The following table shows the prevalence of some of the clinical signs in individuals diagnosed with TSC.

Genetics

TSC is a genetic disorder with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, variable expressivity, and incomplete [10]penetrance.[11] Two-thirds of TSC cases result from sporadic genetic mutations, not inheritance, but their offspring may inherit it from them. Current genetic tests have difficulty locating the mutation in roughly 20% of individuals diagnosed with the disease. So far, it has been mapped to two genetic loci, TSC1 and TSC2.

TSC1 encodes for the protein hamartin, is located on chromosome 9 q34, and was discovered in 1997.[12] TSC2 encodes for the protein tuberin, is located on chromosome 16 p13.3, and was discovered in 1993.[13] TSC2 is contiguous with PKD1, the gene involved in one form of polycystic kidney disease (PKD). Gross deletions affecting both genes may account for the 2% of individuals with TSC who also develop polycystic kidney disease in childhood.[14] TSC2 has been associated with a more severe form of TSC.[15] However, the difference is subtle and cannot be used to identify the mutation clinically. Estimates of the proportion of TSC caused by TSC2 range from 55% to 90%.[16]

TSC1 and TSC2 are both tumor suppressor genes that function according to Knudson's "two hit" hypothesis. That is, a second random mutation must occur before a tumor can develop. This explains why, despite its high penetrance, TSC has wide expressivity.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pathophysiology

Hamartin and tuberin function as a complex which is involved in the control of cell growth and cell division. The complex appears to interact with RHEB GTPase, thus sequestering it from activating mTOR signalling, part of the growth factor (insulin) signalling pathway. Thus, mutations at the TSC1 and TSC2 loci result in a loss of control of cell growth and cell division, and therefore a predisposition to forming tumors. TSC affects tissues from different germ layers. Cutaneous and visceral lesions may occur, including adenoma sebaceum, cardiac rhabdomyomas, and renal angiomyolipomas. The central nervous system lesions seen in this disorder include hamartomas of the cortex, hamartomas of the ventricular walls, and subependymal giant cell tumors, which typically develop in the vicinity of the foramina of Monro.

Molecular genetic studies have defined at least two loci for TSC. In TSC1, the abnormality is localized on chromosome 9q34, but the nature of the gene protein, called hamartin, remains unclear. No missense mutations occur in TSC1. In TSC2, the gene abnormalities are on chromosome 16p13. This gene encodes tuberin, a guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein. The specific function of this protein is unknown. In TSC2, all types of mutations have been reported; new mutations occur frequently. Few differences have yet been observed in the clinical phenotypes of patients with mutation of one gene or the other.

Diagnosis

No pathognomonic clinical signs for TSC complex are seen. Many signs are present in individuals who are healthy (although rarely), or who have another disease. In order to meet diagnostic criteria for TSC complex, an individual must either have: 1) Two or more major criteria; or 2) One major criterion along with two or more minor criteria.

| Major Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Sign | Onset[18] | Note | ||

| 1 | Head | Facial angiofibromas or fibrous cephalic plaque | Infant – adult | At least three | |

| 2 | Fingers and toes | Nontraumatic ungual or periungual fibroma | Adolescent – adult | At least two | |

| 3 | Skin | Hypomelanotic macules | Infant – child | At least three, at least 5 mm in diameter. | |

| 4 | Skin | Shagreen patch (connective tissue nevus) | Child | ||

| 5 | Brain | Cortical dysplasias (includes tubers and cerebral white matter radial migration lines) | Fetus | ||

| 6 | Brain | Subependymal nodule | Child – adolescent | ||

| 7 | Brain | Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | Child – adolescent | ||

| 8 | Eyes | Multiple retinal nodular hamartomas | Infant | ||

| 9 | Heart | Cardiac rhabdomyoma | Fetus | Single or multiple. | |

| 10 | Lungs | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | Adolescent – adult | ||

| 11 | Kidneys | Renal angiomyolipoma | Child – adult | At least two. Together, 10 and 11 count as one major feature. | |

| Minor Criteria | |||||

| Location | Sign | Note | |||

| 12 | Teeth | At least three randomly distributed pits in dental enamel | |||

| 13 | Skin | "Confetti" skin lesions, 1–2 mm hypomelanotic papules | |||

| 14 | Gums | Intraoral fibromas | |||

| 15 | Liver, spleen and other organs | Nonrenal hamartoma | Histologic confirmation is suggested. | ||

| 16 | Eyes | Retinal achromic patch | |||

| 17 | Kidneys | Multiple renal cysts | Histologic confirmation is suggested. | ||

In infants, the first clue is often the presence of seizures, delayed development, or white patches on the skin. A full clinical diagnosis involves:[20][21]

- Taking a personal and family history

- Examining the skin under a Wood's lamp (hypomelanotic macules), the fingers and toes (ungual fibroma), the face (angiofibromas), and the mouth (dental pits and gingival fibromas)

- Cranial imaging with nonenhanced CT or, preferably, MRI (cortical tubers and subependymal nodules)

- Renal ultrasound (angiomyolipoma or cysts)

- An echocardiogram in infants (rhabdomyoma)

- Fundoscopy (retinal nodular hamartomas or achromic patch)

The various signs are then marked against the diagnostic criteria to produce a level of diagnostic certainty:

- Definite – either two major features or one major feature plus two minor features

- Probable – one major plus one minor feature

- Suspect – either one major feature or two or more minor features

Due to the wide variety of mutations leading to TSC, no simple genetic tests are available to identify new cases, nor are any biochemical markers known for the gene defects.[9] However, once a person has been clinically diagnosed, the genetic mutation can usually be found. The search is time-consuming and has a 15% failure rate, which is thought to be due to somatic mosaicism. If successful, this information can be used to identify affected family members, including prenatal diagnosis. As of 2006, preimplantation diagnosis is not widely available.

Management

TSC typically affects multiple organ systems and manifests differently in each patient and in different stages of the life course. Drug therapy, surgery, and other interventions can be effective in managing some of the manifestations and symptoms of TSC.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration has approved several drugs for managing some of the major manifestations of TSC. The antiepileptic medication vigabatrin was approved in 2009 for treatment of infantile spasms and was recommended as first-line therapy for infantile spasms in children with TSC by the 2012 International TSC Consensus Conference.[22][23] Adrenocorticotropic hormone was approved in 2010 to treat infantile spasms.[24] Everolimus was approved for treatment of TSC-related tumors in the brain (subependymal giant cell astrocytoma) in 2010 and in the kidneys (renal angiomyolipoma) in 2012.[25][26] Everolimus also showed evidence of effectiveness at treating epilepsy in some people with TSC.[27] In 2017, the European Commission approved everolimus for treatment of refractory partial-onset seizures associated with TSC.[28]

Neurosurgical intervention may reduce the severity and frequency of seizures in TSC patients. Embolization and other surgical interventions can be used to treat renal angiomyolipoma with acute hemorrhage. Surgical treatments for symptoms of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) in adult TSC patients include pleurodesis to prevent pneumothorax and lung transplantation in the case of irreversible lung failure.[29]

Other treatments that have been used to treat TSC manifestations and symptoms include a ketogenic diet for intractable epilepsy and pulmonary rehabilitation for LAM.[30][23]

Prognosis

The prognosis for individuals with TSC depends on the severity of symptoms, which range from mild skin abnormalities to varying degrees of learning disabilities and epilepsy to severe intellectual disability, uncontrollable seizures, and kidney failure. Those individuals with mild symptoms generally do well and live long, productive lives, while individuals with the more severe form may have serious disabilities. However, with appropriate medical care, most individuals with the disorder can look forward to normal life expectancy.[20]

A study of 30 TSC patients in Egypt found, "...earlier age of seizures commencement (<6 months) is associated with poor seizure outcome and poor intellectual capabilities. Infantile spasms and severely epileptogenic EEG patterns are related to the poor seizure outcome, poor intellectual capabilities and autistic behavior. Higher tubers numbers is associated with poor seizure outcome and autistic behavior. Left-sided tuber burden is associated with poor intellect, while frontal location is more encountered in ASD. So, close follow up for the mental development and early control of seizures are recommended in a trial to reduce the risk factors of poor outcome. Also early diagnosis of autism will allow for earlier treatment and the potential for better outcome for children with TSC."[31]

Leading causes of death include renal disease, brain tumour, lymphangioleiomyomatosis of the lung, and status epilepticus or bronchopneumonia in those with severe mental handicap.[32] Cardiac failure due to rhabdomyomas is a risk in the fetus or neonate, but is rarely a problem subsequently. Kidney complications such as angiomyolipoma and cysts are common, and more frequent in females than males and in TSC2 than TSC1. Renal cell carcinoma is uncommon. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis is only a risk for females with angiomyolipomas.[33] In the brain, the subependymal nodules occasionally degenerate to subependymal giant cell astrocytomas. These may block the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid around the brain, leading to hydrocephalus.

Detection of the disease should be followed by genetic counselling. It is also important to realise that though the disease does not have a cure, symptoms can be treated symptomatically. Hence, awareness regarding different organ manifestations of TSC is important.

Epidemiology

TSC occurs in all races and ethnic groups, and in both genders. The live-birth prevalence is estimated to be between 10 and 16 cases per 100,000. A 1998 study estimated total population prevalence between about 7 and 12 cases per 100,000, with more than half of these cases undetected.[34] These estimates are significantly higher than those produced by older studies, when TSC was regarded as an extremely rare disease. This is due to the invention of CT and ultrasound scanning having enabled the diagnosis of many nonsymptomatic cases. Prior to this, the diagnosis of TSC was largely restricted to severely affected individuals with Vogt's triad of learning disability, seizures, and facial angiofibroma. The total population prevalence estimates have steadily increased from 1:150,000 in 1956, to 1:100,000 in 1968, to 1:70,000 in 1971, to 1:34,200 in 1984, to the present figure of 1:12,500 in 1998. Whilst still regarded as a rare disease, TSC is common when compared to many other genetic diseases.[9]

History

TSC first came to medical attention when dermatologists described the distinctive facial rash (1835 and 1850). A more complete case was presented by von Recklinghausen (1862), who identified heart and brain tumours in a newborn who had only briefly lived. However, Bourneville (1880) is credited with having first characterized the disease, coining the name "tuberous sclerosis", thus earning the eponym Bourneville's disease. The neurologist Vogt (1908) established a diagnostic triad of epilepsy, idiocy, and adenoma sebaceum (an obsolete term for facial angiofibroma).[35]

Symptoms were periodically added to the clinical picture. The disease as presently understood was first fully described by Gomez (1979). The invention of medical ultrasound, CT and MRI has allowed physicians to examine the internal organs of live patients and greatly improved diagnostic ability.

In 2002, treatment with rapamycin was found to be effective at shrinking tumours in animals. This has led to human trials of rapamycin as a drug to treat several of the tumors associated with TSC.[36]

References

- ↑ "Tuberous Sclerosis Fact Sheet". NINDS. 11 April 2006. Retrieved 9 January 2007. (Some text copied with permission.)

- ↑ "Google Ngram Viewer". books.google.com. Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- ↑ Ridler K, Suckling J, Higgins NJ, de Vries PJ, Stephenson CM, Bolton PF, Bullmore ET (2007). "Neuroanatomical correlates of memory deficits in tuberous sclerosis complex". Cereb. Cortex. 17 (2): 261–71. PMID 16603714. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhj144.

- ↑ Harrison JE, Bolton PF (1997). "Annotation: tuberous sclerosis". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 38 (6): 603–14. PMID 9315970. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01687.x.

- ↑ Staley BA, Montenegro MA, Major P, Muzykewicz DA, Halpern EF, Kopp CM, Newberry P, Thiele EA (2008). "Self-injurious behavior and tuberous sclerosis complex: frequency and possible associations in a population of 257 patients". Epilepsy Behav. 13 (4): 650–3. PMID 18703161. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.07.010.

- ↑ Ridler K, Suckling J, Higgins N, Bolton P, Bullmore E (2004). "Standardized whole brain mapping of tubers and subependymal nodules in tuberous sclerosis complex". J. Child Neurol. 19 (9): 658–65. PMID 15563011.

- ↑ Henske EP (2003). "Metastasis of benign tumor cells in tuberous sclerosis complex". Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 38 (4): 376–81. PMID 14566858. doi:10.1002/gcc.10252.

- ↑ Arva, Nicoleta C.; Pappas, John G.; Bhatla, Teena; Raetz, Elizabeth A.; Macari, Michael; Ginsburg, Howard B.; Hajdu, Cristina H. (2012-01-01). "Well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in tuberous sclerosis--case report and review of the literature". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 36 (1): 149–153. PMID 22173120. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e31823d0560.

- 1 2 3 Curatolo (2003), chapter: "Diagnostic Criteria".

- ↑ Baraitser, M; Patton, M A (February 1985). "Reduced penetrance in tuberous sclerosis.". Journal of Medical Genetics. 22 (1): 29–31. ISSN 0022-2593. PMC 1049373

. PMID 3981577.

. PMID 3981577. - ↑ Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Smith RJ, Stephens K, Northrup H, Koenig MK, Au KS. "Tuberous Sclerosis Complex". GeneReviews [Internet]. PMID 20301399.

- ↑ van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, Nellist M, Janssen B, Verhoef S, Lindhout D, van den Ouweland A, Halley D, Young J, Burley M, Jeremiah S, Woodward K, Nahmias J, Fox M, Ekong R, Osborne J, Wolfe J, Povey S, Snell RG, Cheadle JP, Jones AC, Tachataki M, Ravine D, Sampson JR, Reeve MP, Richardson P, Wilmer F, Munro C, Hawkins TL, Sepp T, Ali JB, Ward S, Green AJ, Yates JR, Kwiatkowska J, Henske EP, Short MP, Haines JH, Jozwiak S, Kwiatkowski DJ (1997). "Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34". Science. 277 (5327): 805–8. PMID 9242607. doi:10.1126/science.277.5327.805.

- ↑ European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium (1993). "Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16". Cell. 75 (7): 1305–15. PMID 8269512. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90618-Z.

- ↑ Brook-Carter PT, Peral B, Ward CJ, Thompson P, Hughes J, Maheshwar MM, Nellist M, Gamble V, Harris PC, Sampson JR (1994). "Deletion of the TSC2 and PKD1 genes associated with severe infantile polycystic kidney disease--a contiguous gene syndrome". Nat. Genet. 8 (4): 328–32. PMID 7894481. doi:10.1038/ng1294-328.

- ↑ Dabora SL, Jozwiak S, Franz DN, Roberts PS, Nieto A, Chung J, Choy YS, Reeve MP, Thiele E, Egelhoff JC, Kasprzyk-Obara J, Domanska-Pakiela D, Kwiatkowski DJ (2001). "Mutational analysis in a cohort of 224 tuberous sclerosis patients indicates increased severity of TSC2, compared with TSC1, disease in multiple organs". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68 (1): 64–80. PMC 1234935

. PMID 11112665. doi:10.1086/316951.

. PMID 11112665. doi:10.1086/316951. - ↑ Rendtorff ND, Bjerregaard B, Frödin M, Kjaergaard S, Hove H, Skovby F, Brøndum-Nielsen K, Schwartz M (2005). "Analysis of 65 tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) patients by TSC2 DGGE, TSC1/TSC2 MLPA, and TSC1 long-range PCR sequencing, and report of 28 novel mutations". Hum. Mutat. 26 (4): 374–83. PMID 16114042. doi:10.1002/humu.20227.

- ↑ Northrup H, Krueger DA, International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group (2013). "Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference.". Pediatr Neurol. 49 (4): 243–54. PMC 4080684

. PMID 24053982. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001.

. PMID 24053982. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001. - ↑ Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP (2006). "The tuberous sclerosis complex". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (13): 1345–56. PMID 17005952. doi:10.1056/NEJMra055323.

- ↑ Maruyama H, Seyama K, Sobajima J, Kitamura K, Sobajima T, Fukuda T, Hamada K, Tsutsumi M, Hino O, Konishi Y (2001). "Multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia and lymphangioleiomyomatosis in tuberous sclerosis with a TSC2 gene". Mod. Pathol. 14 (6): 609–14. PMID 11406664. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3880359.

- 1 2 "Tuberous Sclerosis Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 11 April 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2006.

- ↑ "Summary of Clinical guidelines for the care of patients with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex" (PDF). Tuberous Sclerosis Association. April 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2006.

- ↑ "Press Announcements - Sabril Approved by FDA to Treat Spasms in Infants and Epileptic Seizures". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- 1 2 Krueger, Darcy A.; Northrup, Hope; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group (2013-10-01). "Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference". Pediatric Neurology. 49 (4): 255–265. PMC 4058297

. PMID 24053983. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002.

. PMID 24053983. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002. - ↑ "Approval Package for H.P. Acthar Gel" (PDF).

- ↑ "Press Announcements - FDA approves Afinitor for non-cancerous kidney tumors caused by rare genetic disease". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ↑ "FDA Approval for Everolimus". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ↑ French, Jacqueline A; Lawson, John A; Yapici, Zuhal; Ikeda, Hiroko; Polster, Tilman; Nabbout, Rima; Curatolo, Paolo; Vries, Petrus J de; Dlugos, Dennis J. "Adjunctive everolimus therapy for treatment-resistant focal-onset seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis (EXIST-3): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". The Lancet. 388 (10056): 2153–2163. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31419-2.

- ↑ AG, Novartis International. "Novartis drug Votubia® receives EU approval to treat refractory partial-onset seizures in patients with TSC". GlobeNewswire News Room. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ↑ Krueger, Darcy A.; Northrup, Hope; Northrup, Hope; Roberds, Steven; Smith, Katie; Sampson, Julian; Korf, Bruce; Kwiatkowski, David J.; Mowat, David. "Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Surveillance and Management: Recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference". Pediatric Neurology. 49 (4): 255–265. PMC 4058297

. PMID 24053983. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002.

. PMID 24053983. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002. - ↑ Hong, Amanda M.; Turner, Zahava; Hamdy, Rana F.; Kossoff, Eric H. (2010-08-01). "Infantile spasms treated with the ketogenic diet: Prospective single-center experience in 104 consecutive infants". Epilepsia. 51 (8): 1403–1407. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02586.x.

- ↑ Samir H, Ghaffar HA, Nasr M (March 2011). "Seizures and intellectual outcome: clinico-radiological study of 30 Egyptian cases of tuberous sclerosis complex". Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 15 (2): 131–7. PMID 20817577. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2010.07.010.

- ↑ Shepherd CW, Gomez MR, Lie JT, Crowson CS (1991). "Causes of death in patients with tuberous sclerosis". Mayo Clin. Proc. 66 (8): 792–6. PMID 1861550. doi:10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61196-3.

- ↑ Rakowski SK, Winterkorn EB, Paul E, Steele DJ, Halpern EF, Thiele EA (2006). "Renal manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: Incidence, prognosis, and predictive factors". Kidney Int. 70 (10): 1777–82. PMID 17003820. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5001853.

- ↑ O'Callaghan FJ, Shiell AW, Osborne JP, Martyn CN (1998). "Prevalence of tuberous sclerosis estimated by capture-recapture analysis". Lancet. 351 (9114): 1490. PMID 9605811. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78872-3.

- ↑ Curatolo (2003), chapter: "Historical Background".

- ↑ Rott HD, Mayer K, Walther B, Wienecke R (March 2005). "Zur Geschichte der Tuberösen Sklerose (The History of Tuberous Sclerosis)" (PDF) (in German). Tuberöse Sklerose Deutschland e.V. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tuberous sclerosis. |

- tuberous-sclerosis at NIH/UW GeneTests

- GeneReview/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

- The Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance in the United States offers a comprehensive Web site, online discussion groups, and free publications.

- The HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee web pages for TSC1 and TSC2 provide a selection of links for further genetic research.

- The Rothberg Institute For Childhood Diseases have a distributed computing project called CommunityTSC

- Dermatlas: Images of Tuberous sclerosis

- Mass General Hospital's Living with TSC

- The Tuberous Sclerosis Association in the UK has a comprehensive Web site

- Cancer.Net: Tuberous Sclerosis Syndrome

- Tuberous sclerosis symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis