Bosniaks of Serbia

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 145,278 (2011)[3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

Raška District (105,488) Zlatibor District (43,220) Sandžak / Raška historical regions | |

| Languages | |

| Bosnian, Serbian | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other South Slavs |

| Part of a series of articles on

|

| Bosniaks

|

|---|

|

|

Recognized |

|

Kinship · Architecture · Cultural Heritage Sites · Literature · Music (Sevdalinka) · Art · Cinema Cuisine · Sport |

Bosniaks are the fourth largest ethnic group in Serbia after Serbs, Hungarians and Roma, numbering 145,278 or 2.02% of the population according to the 2011 census.[4] They are concentrated in south-western Serbia, and their cultural centre is Novi Pazar.

Demographics

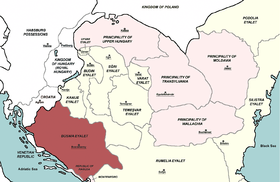

Bosniaks primarily live in south-western Serbia, in the region historically known as Sandžak, which is today divided between the states of Serbia and Montenegro. Colloquially referred to as Sandžaklije by themselves and others, Bosniaks form the majority in three out of six municipalities in the Serbian part of Sandžak: Novi Pazar (77.1%), Tutin (90%) and Sjenica (73.8%) and comprise an overall majority of 59.6%. The town of Novi Pazar is a cultural center of the Bosniaks in Serbia. Many Bosniaks from the Sandžak area left after the fall of the Ottoman Empire to continental Turkey. Over the years a large number of Bosniaks from the Sandžak region left to other countries, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Turkey, Germany, Sweden, United States, Canada, Australia, etc.

Today, the majority of Bosniaks are Sunni Muslim and adhere to the Hanafi school of thought, the largest and oldest school of Islamic law in jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. Some in this region are Albanian by ethnicity and live in villages (Boroštica, Doliće, Ugao) located in the Pešter region. They have adopted a Bosniak identity in censuses, due to past sociopolitical discrimination against Albanians in the former Yugoslavia after World War Two.[5]

History

Two thirds of Sandžak Bosniaks trace their ancestry to the regions of Montenegro proper, from Malesia, region inhabited by Albanians. which they started departing first in 1687, after Turkey lost Boka Kotorska. The trend continued in Old Montenegro after 1711 with the extermination of alleged converts to Islam (“istraga poturica”). Another contributing factor that spurred migration to Sandžak from the Old Montenegro was the fact that the old Orthodox population of Sandžak moved towards Serbia and Habsburg Monarchy (Vojvodina) in two waves, first after 1687, and then, after 1740, basically leaving Sandžak depopulated. The advance of increasingly stronger ethnic Serbs of Montenegro caused additional resettlements out of Montenegro proper in 1858 and 1878, when, upon Treaty of Berlin, Montenegro was recognized as an independent state. While only 20 Bosniak families remained in Nikšić after 1878, the towns like Kolašin, Spuž, Grahovo, and others, completely lost their Bosniak population.

The last segment of Sandžak Bosniaks arrived from a couple of other places. Some Bosniaks came from Slavonia after 1687, when Turkey lost all the lands north of Sava in the Austro-Turkish war. Many more came from Herzegovina in the post-1876 period, after the Herzegovina Rebellion staged by the Serbs against Austro-Hungary and their Muslim subjects. Another wave followed immediately thereafter from both Bosnia and Herzegovina, as the Treaty of Berlin placed the Vilayet of Bosnia under the effective control of Austria-Hungary in 1878. The last wave from Bosnia followed in 1908, when Austria-Hungary officially annexed Bosnia, thereby cutting off all direct ties of Bosnian Muslims to the Ottoman Empire, their effective protector.

Politics

Political organising

The first major political organising of the Sandžak Muslims happened at the Sjenica conference, held in August 1917, during the Austrian-Hungarian occupation of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar. The Muslim representatives at the conference decided to ask the Austrian-Hungarian authorities to separate the Sanjak of Novi Pazar from Serbia and Montenegro and merge it with Bosnia and Herzegovina, or at least to give an autonomy to the region.[6]

After the end of the World War I and the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1918, the Sandžak region also become a part of the newly created country. At the Constitutional Assembly election held in 1920, the Sandžak Muslims voted for the People's Radical Party. The main reason for supporting the radicals was a promise made to several influential Muslims that they would be compensated for losing their lands during the agrarian reform.[7]

In order to protect their interests, the Sandžak Muslims organised themselves jointly with the Albanians in the Džemijet party, that covered the area of the present-day Kosovo, the Republic of Macedonia and Sandžak. The main goal of the Džemijet was the protection of interests of the Slavic Muslims and Albanians. Džemijet was founded in 1919 in Skopje and was led by Nexhip Draga and later by his brother Ferhat Bey Draga. After it was founded in Skopje, branches of the party were soon founded in Kosovo, Sandžak and the rest of Macedonia. District and municipal branches in Sandžak were founded at a meeting of Džemijet held in Novi Pazar in 1922. The meeting was highly attended, and it insisted upon Muslim unity instead of division by various political parties.

Currently the most important political party is the Party of Democratic Action of Sandžak led by Sulejman Ugljanin, which has parliamentary representation and has participated in coalition governments.

Notable people

Politics

- Ahmet Daca, political figure of Sandžak region during World War II

- Ejup Ganić, former president of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Rasim Ljajić, Deputy Prime Minister of Government of Serbia and Minister of Foreign and Internal Trade and Telecommunications

- Sulejman Ugljanin, president of the Party of Democratic Action of Sandžak and the Bosniac National Council

Military people

- Husein Rovčanin, commander of a detachment of Sandžak Muslim militia

- Hasan Zvizdić, commander of a detachment of Sandžak Muslim militia

Religion

- Muamer Zukorlić, president and Chief Mufti of the Islamic Community in Serbia

Sports

- Mustafa Hasanagić, footballer

- Enver Hadžiabdić, footballer

- Adem Ljajić, footballer

- Enver Alivodić, footballer

- Fahrudin Mustafić, footballer

- Mirsad Türkcan, born as Mirsad Jahović, basketball player

- Hedo Türkoğlu, Turkish basketball player

- Alem Toskić, handballer and European Championship silver medalist

- Mirsad Terzić, handballer

- Asmir Kolašinac, shot putter and European Indoor Champion

- Amela Terzić, middle-distance runner and two-time European U23 Champion

- Marco Huck, professional boxer and former WBO cruiserweight champion

Performig arts

- Irfan Mensur, theatre, television and film actor

- Emina Jahović, singer

- Mirza Šoljanin, Bosnian singer

Other

See also

| Part of a series of articles on

|

| Bosniaks

|

|---|

|

|

Recognized |

|

Kinship · Architecture · Cultural Heritage Sites · Literature · Music (Sevdalinka) · Art · Cinema Cuisine · Sport |

References

Notes

- ↑ Bosniak national council, 23. December 2005

- ↑ | National minority council law, "Sl. glasnik RS", br. 72/2009, 20/2014; "Službeni glasnik RS", br. 23/06

- ↑ Census 2011

- ↑ РЗС | Резултати извештаја

- ↑ Andrea Pieroni, Maria Elena Giusti, & Cassandra L. Quave (2011). "Cross-cultural ethnobiology in the Western Balkans: medical ethnobotany and ethnozoology among Albanians and Serbs in the Pešter Plateau, Sandžak, South-Western Serbia." Human Ecology. 39.(3): 335. "The current population of the Albanian villages is partly “bosniakicised”, since in the last two generations a number of Albanian males began to intermarry with (Muslim) Bosniak women of Pešter. This is one of the reasons why locals in Ugao were declared to be “Bosniaks” in the last census of 2002, or, in Boroštica, to be simply “Muslims”, and in both cases abandoning the previous ethnic label of “Albanians”, which these villages used in the census conducted during “Yugoslavian” times. A number of our informants confirmed that the self-attribution “Albanian” was purposely abandoned in order to avoid problems following the Yugoslav Wars and associated violent incursions of Serbian para-military forces in the area. The oldest generation of the villagers however are still fluent in a dialect of Ghegh Albanian, which appears to have been neglected by European linguists thus far. Additionally, the presence of an Albanian minority in this area has never been brought to the attention of international stakeholders by either the former Yugoslav or the current Serbian authorities."

- ↑ Kamberović 2009, p. 94–95.

- ↑ Crnovršanin & Sadiković 2001, p. 287.