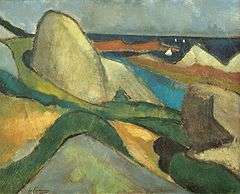

Bords de la Marne

| Bords de la Marne | |

|---|---|

| English: The Banks of the Marne | |

| |

| Artist | Albert Gleizes |

| Year | 1909 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 54 cm × 65 cm (21.25 in × 25.6 in) |

| Location | Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon |

Bords de la Marne, also called Les Bords de la Marne and The Banks of the Marne, is a proto-Cubist oil painting on canvas created in 1909 by the French artist, theorist and writer Albert Gleizes. In this work can be seen a departure from the representation of the observable world. The subject is treated neither as a confined symbolic allegory nor as a cultural background indicated by specific real appearance, but is instead presented in concrete and precise geometric terms. The development of Cubist and abstract art in the work of Gleizes was necessarily a transformation from the synthetic preoccupation with his subject matter. The passage of Gleizes' painting from an epic visionary figuration to total abstraction was foreshadowed during his proto-Cubist period. Bords de la Marne measures 54 × 65 cm, and is currently in the permanent collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.

History

Gleizes' concern for construction, structural rhythms and simplification was dominant even through his short-lived Fauve-like period, when his color brightest and impasto thickest. By treating his subject matter in geometric terms and by modifying curves to become sharp, angled lines, Gleizes consistently held his compositions to the surface of the picture plane. He began to divide the surface into a series of interlocking angles and rectangles of contrasting forms. The overall rose tonality was employed by Gleizes to counter the illusion of depth. In the process Gleizes created some of his first Proto-Cubist works. His awareness of Paul Cézanne—even in the handling of paint—is evident during this period that lasted roughly from 1907 to 1909, though the process of geometric simplification is more akin to Symbolism, Pont Aven and Les Nabis principles than to Cézanne. Bords de la Marne and other painting by Gleizes during this phase (e.g., Paysage dans les Pyrènnes (Landscape in the Pyrenees Mountains), 1908, and Paris, Les Quais, 1908), also bear marked affinity to the work of Henri Le Fauconnier, despite the fact that the two artists had not yet become friends or known about each other's work.[1]

Though the physical scope and appearance of the world at the time reflected the vast changes in progress, Gleizes expected much more. His vision responded to the conditions of modern life but he did not seek to imitate those conditions, as Gleizes later accused the Futurist artists of doing.[2] Gleizes and his former associates of the Abbaye de Créteil (notably Jules Romains, Henri-Martin Barzun and René Arcos) dreamed of a synthetic concept of the possibilities of the future, one of collectivity, multiplicity and simultaneity. "Their vision" writes art historian Daniel Robbins, "invariably encompassed broad subjects which, although dealing with reality, were restricted neither by the limitations of physical perception nor by a separation of scientific fact from intellectual meaning—even symbolic meaning. Even their images of simultaneity were synthetic because scope was too vast, both physically and symbolically, for one man's limited participation".[1]

Structural rhythms

Gleizes' style changed rapidly between 1905 and 1909. From a paint application technique akin to Impressionism and a palette similar to Neo-Impressionism and Fauvism, his painting became more robust. Color and brushwork became simpler, his structural rhythms more pronounced, though softened by curvilinear forms. A synthetic view of the world—presenting the remarkable properties of space, time, multiplicity and diversity—suddenly materialized. These paintings were a visual parallel to the ideals verbally realized in the Abbaye de Créteil poetry.[1]

- Experienced in the treatment of inclusive landscapes (writes Robbins), he nevertheless had to solve the problem of balancing many simultaneous visions on a painted surface. Gleizes mitigated the distortion of distance by linear perspective, by flattening the picture plane; his skies were on the same plane as the simple flat objects in front and, although scale was retained, a form in the distance would be brought to the foreground by making it bright. Every element of the painting had to be reduced to clear planes, treated as uniformly as possible, for attention lavished on any one part would jeopardize the whole dehcate balance. In 1908, although color range expanded in the winter river scenes and contracted in the summer landscapes, the horizon line consist ently crept higher and higher.

Henri Le Fauconnier, living in Brittany in comparative isolation, was pursuing similar ends. A former student at the Académie Julian and a friend of Maurice Denis and Les Nabis, he was painting rocks and seascapes in a progressively geometric fashion. He exhibited his seascapes at the 1909 Salon des Indépendants but Gleizes had not yet exhibited in that salon and appears not to have seen the work until they met through Alexandre Mercereau the same year. Mercereau, perhaps, realized the extent of their common interests.[1]

According to Gleizes, Mercereau is also responsible for having introduced him to Jean Metzinger in 1910—the same year that Mercereau included these three artists in a Moscow exhibition, probably the first Jack of Diamonds Exhibition. Prior to meeting, Gleizes and Metzinger had been linked by Louis Vauxcelles' disparaging comments on "des cubes Blafards"[3] which likely referred to Metzinger's Portrait of Apollinaire and Gleizes' L'Arbre (The Tree) (1910) at the Salon des Indépendants. Mercereau had previously included Gleizes' Les Brumes du Matin sur la Marne in a Russian exhibition of 1908.

- "Given Mercereau's long standing delight in promoting group activity", writes Robbins, "it is easy to recognize his pleasure in having brought together three painters whose works exhibited similar interests and who could be identified with his own synthetic ideals, ideals which had been influential in the Abbaye's development". As organizer of the literary section of the Salon d'Automne of 1909, he was able to introduce Gleizes to painters exhibiting there and to introduce his own concepts to the world of painting".[1]

In 1909 and 1910 a significant group of artists came together through Mercereau. The entire group—including Allard, Barzun, Beauduin, Castiaux, Jouve, Divoire, Parmentier, Marinetti, Brâncuși, Varlet and even Apollinaire and Salmon—became sympathetic to the ideas of the Abbaye. During the Summer of 1908 Gleizes and Mercereau organized a great Journée portes ouvertes at the Abbaye, with poetry readings, music and exhibitions. Participants included the Italian Symbolist poet, and soon principle theorist of Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși.[4][5][6]

Salmon and Apollinaire were only peripheral members, participating in divers literary and artistic circles, but clearly Apollinaire's conception of Cubism was influenced by the epic notions found in the old Abbaye circle. In his preface to the 1911 Brussels Indépendants, Apollinaire wrote:

...thus has come a simple and noble art, expressive and measured, eager to discover beauty, and entirely ready to tackle those vast subjects which the painters of yesterday did not dare to undertake, abandoning them to the presumptuous, old-fashioned and boring daubers of the official Salons.

This conception is not based on the studies of Picasso and Braque (what became known years later as the analytical Cubism), which had annihilated subject matter almost entirely and confined it to exceedingly flat space. Instead, it suggests the broad concepts held by the Mercereau-Gleizes circle, concepts at that time visible only in the paintings of Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger. The subjects treated by these Cubists differed significantly from the isolated still lifes or figures chosen by Picasso and Braque.[1]

Allard wrote of Gleizes, Le Fauconnier and Metzinger, in a review of the 1910 Salon d'Automne:

Thus is born at the antipodes of impressionism an art which cares little to imitate the occasional cosmic episode, but which offers to the intelligence of the spectator the essential elements of a synthesis in time, in all its pictorial fullness.[7]

The development of abstract art in the work of Gleizes and Delaunay was necessarily a transformation from the synthetic preoccupation with epic themes. In order to understand the passage of Gleizes' painting from an epic visionary figuration to abstraction, it is important to understand his proto-Cubist period and its differences from the proto-Cubist works of Picasso and Braque.

If Bords de la Marne involved the interaction of vast space with geometry, Gleizes' work would soon project speed and action, with simultaneity, commerce, sport, and flight: with the modern city and the ancient country, with boats, the harbor and the bridge and, above all, with time. The dimension of time—involving memory, tradition and accumulated cultural thought—created the reality of the world.

"In poetry", writes Robbins, "this post-symbolist attempt to achieve new forms had to break decisively with the old unities of time, place and action. Unity of scene did not correspond with the reality of modem life; unity of time did not correspond with the culturally known and anticipated effects of change. That is why Mercereau (as Metzinger noted[5]) shifted his scenes so violently, why Barzun tried to solve the problem of simultaneously developing lines of action by choral chanting. Similarly Gleizes and his painter friends sought to create a vision free from introverted or obscure imagery which could treat collective and simultaneous factors. This necessitated a new kind of allegory opposed to the old meaning which presented one thing as the symbolic equivalent of another. A tentative precedent perhaps existed in Courbet's Real Allegory which, however, might have been considered an allegorical failure by Gleizes and Metzinger because Courbet "did not suspect that the visible world only became the real world by the operation of thought".[1][8]

A departure from the representation of the observable world is quite apparent in Bords de la Marne. This subject was treated neither as a confined symbolic allegory nor as a cultural background indicated by specific real appearance, but was instead presented in concrete and precise geometric terms. Gleizes' Bords de la Marne is not strictly an anecdotal scene. Rather, it represents a multiple panorama; the analysis of volume relationships in a departure from the grand principles of structure, color and inspiration, a permanently changing land. Gleizes confronts us not with one action or place, but with many: not with one time, but with past and future as well as present.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Robbins, Daniel, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Albert Gleizes, 1881-1953, A Retrospective Exhibition, 1964

- ↑ Albert Gleizes, Des 'ismes'; vers une Renaissance plastique, Tradition et Cubisme, Paris, Povolovzky, 1927, p. 168 (first published in La Vie des Lettres et des Arts, 1921)

- ↑ Louis Vauxcelles, Gil Bias, March 18, 1910. Quoted in John Golding, Cubism, London, 1959, p. 22. See Toison d'Or, Moscow, 1908, nos. 7-10, p. 15

- ↑ Peter Brooke, Albert Gleizes, Chronology of his life, 1881-1953

- 1 2 Jean Metzinger, Alexandre Mercereau, Vers et Prose, Paris, no. 27, October–December, 1911, p. 122

- ↑ Daniel Robbins, From Symbolism to Cubism: The Abbaye of Créteil", The Art Journal, 1963-64, XXIII 2. pp. 111-116

- ↑ Roger Allard, Au Salon d'Automne de Paris, L'Art Libre, Lyon, October–November, 1910

- ↑ Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, Du "Cubisme", published by Eugène Figuière, Paris, 1912. The authors begin their work with a discussion of Courbet

External links

- Fondation Albert Gleizes

- Ministère de la Culture (France) – Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine, Albert Gleizes

- Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Grand Palais, Agence photographique, page 1 of 6

- André Salmon, Artistes d'hier et d'aujourd'hui, L'Art Vivant, 6th edition, Paris, 1920