Book of Jonah

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Book of Jonah is one of the Prophets in the Bible. It tells of a Hebrew prophet named Jonah son of Amittai who is sent by God to prophesy the destruction of Nineveh but tries to escape the divine mission.[1] Set in the reign of Jeroboam II (786–746 BC), it was probably written in the post-exilic period, some time between the late 5th to early 4th century BC.[2] The story has a long interpretive history and has become well-known through popular children's stories. In Judaism it is the Haftarah, read during the afternoon of Yom Kippur in order to instill reflection on God's willingness to forgive those who repent;[3] it remains a popular story among Christians. It is also retold in the Koran.

Narrative

Unlike the other Prophets, the book of Jonah is almost entirely narrative, with the exception of the psalm in chapter 2. The actual prophetic word against Nineveh is given only in passing through the narrative. As with any good narrative, the story of Jonah has a setting, characters, a plot, and themes. It also relies heavily on such literary devices as irony.

Outline

- Jonah Flees His Mission (chapters 1-2)

- Jonah's Commission and Flight (1:1-3)

- The Endangered Sailors Cry to Their gods (1:4-6)

- Jonah's Disobedience Exposed (1:7-10)

- Jonah's punishment and Deliverance (1:11-2:1;2:10)

- His Prayer of Thanksgiving (2:2-9)

- Jonah Reluctantly fulfills His Mission (chapters 3-4)

- Jonah's Renewed Commission and Obedience (3:1-4)

- The Endangered Ninevites' Repentant Appeal to the Lord (3:5-9)

- The Ninevites' Repentance Acknowledged (3:10-4:4)

- Jonah's Deliverance and Rebuke (4:5-11)[4]

Setting

Nineveh, where Jonah preached, was the capital of the ancient Assyrian empire, which fell to the Babylonians and the Medes in 612 BC. The book calls Nineveh a “great city,” referring to its size [Jonah 3:3 + 4:11] and perhaps to its affluence as well. (The story of the city’s deliverance from judgment may reflect an older tradition dating back to the 8th–7th century BC) Assyria often opposed Israel and eventually took the Israelites captive in 722–721 BC (see History of ancient Israel and Judah). The Assyrian oppression against the Israelites can be seen in the bitter prophecies of Nahum.

Characters

The story of Jonah is a drama between a passive man and an active God. Jonah, whose name literally means "dove," is introduced to the reader in the very first verse. The name is decisive. While many other prophets had heroic names (e.g., Isaiah means "God has saved"), Jonah's name carries with it an element of passivity.

Jonah's passive character is contrasted with the other main character: Yahweh. God's character is altogether active. While Jonah flees, God pursues. While Jonah falls, God lifts up. The character of God in the story is progressively revealed through the use of irony. In the first part of the book, God is depicted as relentless and wrathful; in the second part of the book, He is revealed to be truly loving and merciful.

The other characters of the story include the sailors in chapter 1 and the people of Nineveh in chapter 3. These characters are also contrasted to Jonah's passivity. While Jonah sleeps in the hull, the sailors pray and try to save the ship from the storm (1:4–6). While Jonah passively finds himself forced to act under the Divine Will, the people of Nineveh actively petition God to change his mind.

Plot

In the Bible

The plot centers on a conflict between Jonah and God. God calls Jonah to proclaim judgment to Nineveh, but Jonah resists and attempts to flee. He goes to Joppa and boards a ship bound for Tarshish. God calls up a great storm at sea, and, at Jonah's insistence, the ship's crew reluctantly cast Jonah overboard in an attempt to appease God. A great sea creature, sent by God, swallows Jonah. For three days and three nights Jonah languishes inside the fish's belly. He says a prayer in which he repents for his disobedience and thanks God for His mercy. God speaks to the fish, which vomits out Jonah safely on dry land.

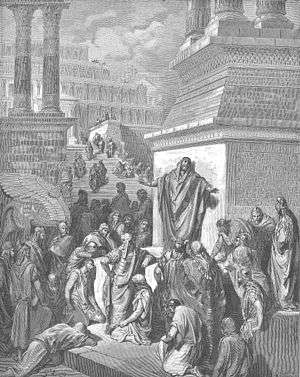

After his rescue, Jonah obeys the call to prophesy against Nineveh, causing the people of the city to repent and God to forgive them. Jonah is furious, however, and angrily tells God that this is the reason he tried to flee from Him, as he knew Him to be a just and merciful God. He then beseeches God to kill him, a request which is denied when God causes a tree to grow over him, giving him shade. Initially grateful, Jonah's anger returns the next day, when God sends a worm to eat the plant, withering it, and he tells God that it would be better if he were dead. God then points out: "You are concerned about the bush, for which you did not labour and which you did not grow; it came into being in a night and perished in a night. And should I not be concerned about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who do not know their right hand from their left, and also many animals? (NRSV)"

Ironically, the relentless God demonstrated in the first chapter is shown to be the merciful God in the last two chapters (see 3:10). Equally ironic, despite not wanting to go to Nineveh and follow God's calling, Jonah becomes one of the most effective prophets of God. As a result of his preaching, the entire population of Nineveh repents before the Lord and is spared destruction. The author indicates that the city "has more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who cannot tell their right hand from their left" (4:11a, NIV). While some commentators see this number (120,000) as a somewhat pejorative reference to ignorant or backward Ninevites, most commentators take it to refer to young infants, thus implying a population considerably larger than 120,000.[5]

In the Koran

Islam also tells the story of the Prophet Jonah in the Koran. Similar to the Bible, the Koran states that Jonah was sent to his people to deliver a message to worship only one God (the Judeo-Christian God of Abraham) and refrain from evil behavior. However Johah became angry with his people when they refused to listen and ignores him. Jonah gave up on his people and left his community without having instruction from God. “And remember when he (Jonah) went off in anger.” (Quran 21:87)

According to Islam, after Jonah left his people the sky turned red as fire and the people were filled with fear. Jonah's people repented to God and prayed that Jonah would return to guide them to the Straight Path. God accepted their repentance and the sky returned to normal.

As told in the Koran, Jonah boarded a ship to be far away from his people. While on the ship the calm sea became violent and was tearing at the boat. After throwing their belongings overboard without any positive change, the passengers cast lots to throw someone overboard to reduce the weight. Twice Jonah's name was drawn to be thrown overboard, which surprised the passengers because Jonah as perceived as a righteous and pious man. Jonah understood this was not a coincidence but his destiny and he jumped into the violent sea and was swallowed by a "giant fish." Many believe this fish was a whale.

The strong acid from fish's belly began to eat away at Jonah's skin and he began to repeatedly call out to God for help by saying: "None has the right to be worshipped but you oh God, glorified are you and truly I have been one of the wrongdoers!” (Quran 21:87)

Islam teaches that God accepted Jonah's repentance and commanded the giant fish to spit Jonah out onto the shore. Jonah was in pain and his skin was burned from the acid in the fish's belly. Jonah repeated his prayer and God relieved him by having a vine (gourd) cover his body to protect him and also provided him with food.

The Koran states: "And, verily, Jonah was one of the Messengers. When he ran to the laden ship, he agreed to cast lots and he was among the losers, then a big fish swallowed him and he had done an act worthy of blame. Had he not been of them who glorify God, he would have indeed remained inside its belly (the fish) until the Day of Resurrection. But We cast him forth on the naked shore while he was sick and We caused a plant of gourd to grow over him. And We sent him to a hundred thousand people or even more, and they believed, so We gave them enjoyment for a while.” (Quran 37:139-148).

Jonah returned to be with his people and guide them. The prayer made by Jonah while in the fish's belly can be used to help anyone in times of distress: "None has the right to be worshipped but you oh God, glorified are you and truly I have been one of the wrongdoers!” (Quran 21:87).

Interpretive history

Early Jewish interpretation

The story of Jonah has numerous theological implications, and this has long been recognized. In early translations of the Hebrew Bible, Jewish translators tended to remove anthropomorphic imagery in order to prevent the reader from misunderstanding the ancient texts. This tendency is evidenced in both the Aramaic translations (e.g. the Targums) and the Greek translations (e.g. the Septuagint). As far as the Book of Jonah is concerned, Targum Jonah offers a good example of this.

Targum Jonah

In Jonah 1:6, the Masoretic Text (MT) reads, "...perhaps God will pay heed to us...." Targum Jonah translates this passage as: "...perhaps there will be mercy from the Lord upon us...." The captain's proposal is no longer an attempt to change the divine will; it is an attempt to appeal to divine mercy. Furthermore, in Jonah 3:9, the MT reads, "Who knows, God may turn and relent [lit. repent]?" Targum Jonah translates this as, "Whoever knows that there are sins on his conscience let him repent of them and we will be pitied before the Lord." God does not change His mind; He shows pity.

Dead Sea Scrolls

Fragments of the book were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) (4Q76 a.k.a. 4QMinorProphetsa, Col V-VI, frags. 21–22; 4Q81 a.k.a. 4QMinorProphetsf, Col I and II; and 4Q82 a.k.a. 4QMinorProphetsg, Frags. 76–91), most of which follows the Masoretic Text closely and with Mur XII reproducing a large portion of the text.[6] As for the non-canonical writings, the majority of references to biblical texts were made by argumentum ad verecundiam. The Book of Jonah appears to have served less purpose in the Qumran community than other texts, as the writings make no references to it.[7]

Early Christian interpretation

New Testament

The earliest Christian interpretations of Jonah are found in the Gospel of Matthew (see Matthew 12:38–42 and 16:1–4) and the Gospel of Luke (see Luke 11:29–32). Both Matthew and Luke record a tradition of Jesus’ interpretation of the Book of Jonah (notably, Matthew includes two very similar traditions in chapters 12 and 16). As with most Old Testament interpretations found in the New Testament, Jesus’ interpretation is primarily “typological” (see Typology (theology)). Jonah becomes a “type” for Jesus. Jonah spent three days in the belly of the fish; Jesus will spend three days in the grave. Here, Jesus plays on the imagery of Sheol found in Jonah’s prayer. While Jonah metaphorically declared, “Out of the belly of Sheol I cried,” Jesus will literally be in the belly of Sheol. Finally, Jesus compares his generation to the people of Nineveh. Jesus fulfills his role as a type of Jonah, however his generation fails to fulfill its role as a type of Nineveh. Nineveh repented, but Jesus' generation, which has seen and heard one even greater than Jonah, fails to repent. Through his typological interpretation of the Book of Jonah, Jesus has weighed his generation and found it wanting.

Augustine of Hippo

The debate over the credibility of the miracle of Jonah is not simply a modern one. The credibility of a human being surviving in the belly of a great fish has long been questioned. In c. 409 AD, Augustine of Hippo wrote to Deogratias concerning the challenge of some to the miracle recorded in the Book of Jonah. He writes:

The last question proposed is concerning Jonah, and it is put as if it were not from Porphyry, but as being a standing subject of ridicule among the Pagans; for his words are:“In the next place, what are we to believe concerning Jonah, who is said to have been three days in a whale’s belly? The thing is utterly improbable and incredible, that a man swallowed with his clothes on should have existed in the inside of a fish. If, however, the story is figurative, be pleased to explain it. Again, what is meant by the story that a gourd sprang up above the head of Jonah after he was vomited by the fish? What was the cause of this gourd’s growth?” Questions such as these I have seen discussed by Pagans amidst loud laughter, and with great scorn.

— (Letter CII, Section 30)

Augustine responds that if one is to question one miracle, then one should question all miracles as well (section 31). Nevertheless, despite his apologetic, Augustine views the story of Jonah as a figure for Christ. For example, he writes: "As, therefore, Jonah passed from the ship to the belly of the whale, so Christ passed from the cross to the sepulchre, or into the abyss of death. And as Jonah suffered this for the sake of those who were endangered by the storm, so Christ suffered for the sake of those who are tossed on the waves of this world." Augustine credits his allegorical interpretation to the interpretation of Christ himself (Matt. 12:39,40), and he allows for other interpretations as long as they are in line with Christ's.

Medieval commentary tradition

The Ordinary Gloss

The Ordinary Gloss, or Glossa Ordinaria, was the most important Christian commentary on the Bible in the later Middle Ages. "The Gloss on Jonah relies almost exclusively on Jerome’s commentary on Jonah (c. 396), so its Latin often has a tone of urbane classicism. But the Gloss also chops up, compresses, and rearranges Jerome with a carnivalesque glee and scholastic directness that renders the Latin authentically medieval."[8] "The Ordinary Gloss on Jonah" has been translated into English and printed in a format that emulates the first printing of the Gloss.[9]

The relationship between Jonah and his fellow Jews is ambivalent, and complicated by the Gloss's tendency to read Jonah as an allegorical prefiguration of Jesus Christ. While some glosses in isolation seem crudely supersessionist (“The foreskin believes while the circumcision remains unfaithful”), the prevailing allegorical tendency is to attribute Jonah’s recalcitrance to his abiding love for his own people and his insistence that God’s promises to Israel not be overridden by a lenient policy toward the Ninevites. For the glossator, Jonah’s pro-Israel motivations correspond to Christ’s demurral in the Garden of Gethsemane (“My Father, if it be possible, let this chalice pass from me” [Matt. 26:39]) and the Gospel of Matthew’s and Paul’s insistence that “salvation is from the Jews” (Jn. 4:22). While in the Gloss the plot of Jonah prefigures how God will extend salvation to the nations, it also makes abundantly clear—as some medieval commentaries on the Gospel of John do not—that Jonah and Jesus are Jews, and that they make decisions of salvation-historical consequence as Jews.

Modern

Roman Catholic author Terry Eagleton has written, "There are writers who consider their work to be examples of high seriousness when they are hilariously, unintentionally funny. ... Another example is the Book of Jonah, which is probably not intended to be funny but which is brilliantly comic without seeming to be aware of it."[10]

Jonah and the "big fish"

The Hebrew text of Jonah 2:1 (1:17 in English translation), reads dag gadol (Hebrew: דג גדול), which literally means "great fish." The Septuagint translates this into Greek as ketos megas, (Greek: κητος μεγας), "huge fish"; in Greek mythology the term was closely associated with sea monsters.[11] Saint Jerome later translated the Greek phrase as piscis granda in his Latin Vulgate, and as cetus in Matthew 12:40. At some point, cetus became synonymous with whale (cf. cetyl alcohol, which is alcohol derived from whales). In his 1534 translation, William Tyndale translated the phrase in Jonah 2:1 as "greate fyshe," and he translated the word ketos (Greek) or cetus (Latin) in Matthew 12:40 as "whale". Tyndale's translation was later followed by the translators of the King James Version of 1611 and has enjoyed general acceptance in English translations.

In the line 2:1 the book refers to the fish as dag gadol, "great fish", in the masculine. However, in the 2:2, it changes the gender to daga, meaning female fish. The verses therefore read: "And the lord provided a great fish (dag gadol, masculine) for Jonah, and it swallowed him, and Jonah sat in the belly of the fish (still male) for three days and nights; then, from the belly of the (daga, female) fish, Jonah began to pray." The peculiarity of this change of gender led the later rabbis to reason that this means Jonah was comfortable in the roomy male fish, so he didn't pray, but that God then transferred him to a smaller, female fish, in which the prophet was uncomfortable, so that he prayed.

Jonah and the gourd vine

The book closes abruptly (Jonah 4) with an epistolary warning[12] based on the emblematic trope of a fast-growing vine present in Persian narratives, and popularized in fables such as The Gourd and the Palm-tree during the Renaissance, for example by Andrea Alciato.

St. Jerome differed[13] with St. Augustine in his Latin translation of the plant known in Hebrew as קיקיון (qīqayōn), using hedera (from the Greek, meaning "ivy") over the more common Latin cucurbita, "gourd", from which the English word gourd (Old French coorde, couhourde) is derived. The Renaissance humanist artist Albrecht Dürer memorialized Jerome's decision to use an analogical type of Christ's "I am the Vine, you are the branches" in his woodcut Saint Jerome in His Study.

References

- ↑ II Kings 14:25

- ↑ Mercer Dictionary of the Bible.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-11-18. Retrieved 2009-08-18. United Jewish Communities (UJC), "Jonah's Path and the Message of Yom Kippur."

- ↑ NIV Bible (Large Print ed.). (2007). London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

- ↑ Brynmor F. Price and Eugene A. Nida, A Handbook on the Book of Jonah, United Bible Societies

- ↑ David L. Washburn, A Catalog of Biblical Passages in the Dead Sea Scrolls (Brill, 2003), 146.

- ↑ James C. Vanderkam, The Dead Sea Scrolls Today (Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1994), 151

- ↑ Ryan McDermott, trans., "The Ordinary Gloss on Jonah," PMLA 128.2 (2013): 424–38.

- ↑ "The Ordinary Gloss on Jonah".

- ↑ Eagleton, Terry (2013). How to Read Literature. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-300-19096-0.

- ↑ See http://www.theoi.com/Ther/Ketea.html for more information regarding Greek mythology and the Ketos

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Jonah".

- ↑ citing Peter W. Parshall, "Albrecht Dürer's Saint Jerome in his Study: A Philological Reference," from The Art Bulletin 53 (September 1971), pp. 303–5 at http://www.oberlin.edu/amam/DurerSt.Jerome.htm

Further reading

- De La Torre, Miguel A., "Liberating Jonah: Toward a Biblical Ethics of Reconciliation," Orbis Books, 2007.

External links

- An English translation of the most important medieval Christian commentary on Jonah, "The Ordinary Gloss on Jonah," PMLA 128.2 (2013): 424–38.

- A brief introduction to Jonah

-

Jonah public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Jonah public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

| Book of Jonah | ||

| Preceded by Obadiah |

Hebrew Bible | Succeeded by Micah |

| Christian Old Testament | ||