Boogie Chillen'

| "Boogie Chillen'" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by John Lee Hooker | |

| B-side | "Sally May" |

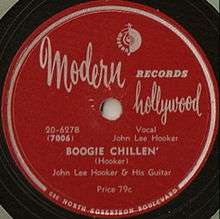

| Released | November 1948[1] |

| Format | 10-inch 78 rpm record |

| Recorded | September 1948[1][lower-alpha 1] |

| Studio | United Sound Systems, Detroit, Michigan |

| Genre | Blues |

| Length | 3:11 |

| Label | Modern (no. 627) |

| Songwriter(s) | John Lee Hooker |

| Producer(s) | Bernie Besman |

"Boogie Chillen'" or "Boogie Chillun"[lower-alpha 2] is a blues song first recorded by John Lee Hooker in 1948. It is a solo performance featuring Hooker's vocal, electric guitar, and rhythmic foot stomps. The lyrics are partly autobiographical and alternate between spoken and sung verses. The song was his debut record release and in 1949, it became the first "down-home" electric blues song to reach number one in the R&B records chart.

Hooker's song was part of a trend in the late 1940s to a new style of urban electric blues based on earlier Delta blues idioms. Although it is called a boogie, it resembles early North Mississippi Hill country blues rather than the boogie-woogie piano-derived style of the 1930s and 1940s. Hooker gave credit to his stepfather, Will Moore, who taught him the rhythm of "Boogie Chillen'" ("chillen'" is a phonetical approximation of Hooker's pronunciation of "children") when he was a teenager. Some of the song's lyrics are derived from earlier blues songs.

Hooker's guitar work on the song inspired several well-known guitarists to take up the instrument. With its driving style and focus on rhythm, it is also considered a forerunner of rock and roll. Music critic Cub Koda calls the guitar figure from "Boogie Chillen'" "the riff that launched a million songs".[4] Several rock musicians have patterned successful songs either directly or indirectly on Hooker's many versions of "Boogie Chillen'". These include songs by boogie rock band Canned Heat, who also recorded a well-received version with Hooker. One of ZZ Top's best-known hits, "La Grange", uses elements of the song, which led to legal action by the song's publisher and resulted in changes to American copyright law.

Background

In 1943, Hooker moved to Detroit, Michigan, for employment opportunities in the city's wartime vehicle manufacturing factories.[5] There he was attracted to the music clubs along Hastings Street in Black Bottom/Paradise Valley, the cultural center of the city's black community.[6] He recounts his experience in the narrative to "Boogie Chillen'":[7]

When I first come to town people, I was walkin' down Hastings Street

I heard everybody talkin' about, Henry's Swing Club

I decided I'd drop in there that night, and when I got there

I say 'Yes, people!', yes they was really havin' a ball!

Yes, I know

Boogie chillen'!

By 1948, Hooker came to the attention of Elmer Barbee, a local record shop owner.[8] Barbee arranged to have several demos recorded.[8] He or Hooker later presented them to Bernie Besman, who ran the Detroit area's only professional record company.[3] Although Hooker had played mostly with an ensemble at that time, Besman decided to record him solo.[9] This put the attention solely on the singer/guitarist,[1] in contrast to the prevailing jump blues style, which emphasized ensemble instrumentation. Recent hit singles by Muddy Waters and Lightnin' Hopkins had also used this stripped-down, electrified Delta blues-inspired approach.[10]

Composition and lyrics

"Boogie Chillen'" is described by music critic Bill Dahl as "blues as primitive as anything then on the market; Hooker's dark, ruminative vocals were backed only by his own ringing, heavily amplified guitar and insistently pounding foot".[6] In an interview, Hooker shared how he came up with "Boogie Chillen'":

I wrote that song in Detroit when I was sittin' around strummin' my guitar. The thing come into me, you know? I heard [my stepfather] Will Moore done [sic] it years and years before. I was a little kid from down South, and I heard him do a song like that, but he didn't call it 'Boogie Chillen.' But it had that beat, and I just kept that beat up and I called it 'Boogie Chillen.'[11]

He performed the song in clubs before recording it and called it "Boogie Woogie" before settling on "Boogie Chillen'".[12] According to musicologist Robert Palmer, "The closest thing to it on records is 'Cottonfield Blues', recorded by Garfield Akers and Joe Callicott, two guitarists from the hill country of northern Mississippi, in 1929. Essentially, it was a backcountry, pre-blues sort of music—a droning, open-ended stomp without a fixed verse form that lent itself to building up to a cumulative, trancelike effect".[13]

Hooker's vocal alternates between sung and spoken sections.[14] Commenting on Hooker's vocal sections, music historian Ted Gioia notes, "The song has almost no melody. Even less harmony. In fact, it is hard to call it a song. It's more like a bit of jive steam of consciousness in 4/4 time."[15] Some of the lyrics are borrowed from earlier songs that date back to the beginning of the blues.[16] The opening line "My mama she didn't allow me to stay out all night long" has origins in "Mama Don't Allow", an old dance song.[16] Several songs were recorded in the 1920s with similar titles.[17] "Boogie No. 3" by boogie-woogie pianist Cow Cow Davenport has sung and spoken sections and includes the lines, "I don't care what Grandma don't allow, play my music anyhow, Grandma's don't 'llow no music playin' in here".[18] Hooker's first and second takes of the song include similar verses and the narrative about Henry's Swing Club, but do not include the crucial mid-song hook "Boogie, chillen'!" before the guitar break, which gives the song its lyrical identity.[19]

A key feature of the song is the driving guitar rhythmic figure centered on one chord, with "accents that fell fractionally ahead of the beat".[5] Music journalist Charles Shaar Murray describes it as a "rocking dance piece ... its structure is utterly free-form, its basic beat is the jumping, polyrhythmic groove which he [Hooker] learned in the Delta".[20] In an interview with B.B. King, Hooker confirmed that he used an open G guitar tuning technique for his guitar,[21] although he usually used a capo, raising the pitch to B (1948), A♭ (1959), or A (1970).[22] He also employed hammer-on and pull-off techniques, which are described as "a slurred ascending bass line played on the fifth string [tonic]" by music writer Lenny Carlson.[22] Although it is titled a "boogie", it does not resemble the earlier boogie-woogie style.[5] Boogie-woogie is based on a left-hand piano ostinato or walking-bass line and, as performed on guitar, forms the popular 1940s instrumental "Guitar Boogie".[5][lower-alpha 3] Rather than being derivative, Hooker's boogie becomes "as overwhelmingly personal a piece as anything ever done in the blues".[23]

Recording and release

In September 1948, Besman arranged recording sessions for Hooker at United Sound studios in Detroit.[1] Several songs were recorded with Hooker's vocals and amplified guitar.[3] To make the sound fuller, a microphone was set up in a pallet that was placed under Hooker's foot.[24] According to Besman's account, a primitive echo-chamber effect was created by feeding Hooker's foot-stomp rhythm into a speaker in a toilet bowl, which in turn was miked and returned to a speaker in the studio in front of Hooker's guitar, thus giving it a "big" or more ambient sound.[24] Three takes of Hooker's performance were recorded, the last providing the master for "Boogie Chillen'".[25]

Even though Besman had his own record label, Sensation Records, he licensed "Boogie Chillen'" to Los Angeles-based Modern Records.[3] On November 3, 1948, it was released nationally and Hooker commented on its immediate appeal: "The thing caught afire. It was ringin' all around the country. When it come out, every juke box you went to, every place you went to ... they were playing it there".[5] Because of the response, Nashville, Tennessee, radio station WLAC, a 50,000 watt clear-channel station that reached fifteen states and Canada, played the song ten times in a row during one broadcast night.[26] It entered the Billboard Race Records chart on January 8, 1949, where it remained for eighteen weeks, and reached number one on February 19, 1949.[27] It became the most popular race record of 1949[28] and reportedly sold "several hundred thousand"[29] to one million[30] copies.[lower-alpha 4] In an experience similar to Muddy Waters' 1950 hit "Rollin' Stone",[32] the song's popularity allowed Hooker to give up his factory job and concentrate on music.[5]

Early influence

Besides its commercial success, "Boogie Chillen'" had a big impact on blues and R&B musicians. B.B. King, who was a disc jockey at Memphis, Tennessee, radio station WDIA at the time, regularly featured Hooker's song.[33] He recalled:

[There was] hardly anybody around who was playing at that time didn't play 'Boogie Chillen.' That's just how heavy it was ... I, for one, and many others [musicians] who would go out and play—if you didn't play 'Boogie Chillen' at that time, people probably look at you and wonder what was wrong with you. It was such a big record.[34]

Murray likens the song to "the R&B equivalent of punk rock" or superficially simple enough not to intimidate beginners.[35] It interested the eleven-year-old Bo Diddley: "I think the first record I paid attention to was John Lee Hooker's 'Boogie Chillen,' ... When I found John Lee Hooker on the radio, I said, 'If that guy can play, I know I can.' I mean John Lee's got a hell of a style".[34] In an interview, Buddy Guy described learning to play "Boogie Chillen'" at age thirteen: "that was the first thing I thought I learned how to play that I knew sounded right when someone would listen."[34] Guy later recorded a version with Junior Wells for their 1981 album Alone & Acoustic. Albert Collins also recalled that it was the first song he learned to play.[34]

The success of "Boogie Chillen'" brought numerous offers for John Lee Hooker to record for other record companies. Because he received little remuneration from the sales of his record, Hooker readily accepted the opportunities to generate income.[36] This led to his recording using a variety of pseudonyms, including Texas Slim, Little Pork Chops, Delta John, Birmingham Sam, the Boogie Man, Johnny Williams, John Lee Booker, John Lee Cooker, and others for such labels as King, Danceland, Regent, Savoy, Acorn, Prize, Staff, Gotham, Gone, Chess, and Swing Time.[6]

Later Hooker versions

The demand for "Boogie Chillen'" remained high enough for Hooker to re-record the song several times.[16] In 1950, he recorded a faster version with different lyrics as "Boogie Chillen' #2" for Bernie Besman's Sensation label (also issued by Regal).[37] Modern Records released an edited version in 1952 titled "New Boogie Chillun". After Hooker began his association with Vee-Jay Records, he recorded "Boogie Chillun" in 1959, which closely follows the original single.[38] Because of the similarity, the 1959 version is sometimes misidentified as the 1948 version and vice versa (at 2:36, the Vee-Jay version is about a half a minute shorter than the original).[39]

The first two takes from the September 1948 Detroit recording session began appearing on various compilation albums in the 1970s, sometimes with the titles "John Lee's Original Boogie" and "Henry's Swing Club".[3] Meanwhile, Modern and its associated labels including Kent and Crown reissued the song several times.

From the 1960s onwards, Hooker recorded several studio and live renditions of "Boogie Chillen'",[40] with guest musicians such as Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones. In 1970, he recorded an updated version of the song, titled "Boogie Chillen' No. 2", with the blues rock group Canned Heat for their joint album, Hooker 'n Heat.[41] Blues historian Gerard Herzhaft describes the performance as a "memorable one".[16] It combines Hooker's vocal and Canned Heat's signature boogie rock backing, as heard in the group's jam song "Fried Hockey Boogie" (itself an adaptation of "Boogie Chillen'").[4] Despite being over eleven minutes long with extended guitar and harmonica solos, it remains as "full of the same swagger as the original".[41]

Recognition and legacy

In 1985, Hooker's 1948 recording of "Boogie Chillen'" was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame. Writing for the Foundation, blues historian Jim O'Neal noted it was "the first down-home electric blues record to achieve No. 1 chart status and its success, together with that of the Hooker hits that followed, inspired record companies to search out the new electric generation of country bluesmen".[42] In 1999, it received a Grammy Hall of Fame Award[43] and is included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame list of the "500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll".[44] "Boogie Chillen'" was added to the U.S. National Recording Registry in 2008, which noted that "the driving rhythm and confessional lyrics have guaranteed its place as an influential and enduring blues classic".[45] Authors Jim Dawson and Steve Propes included it in their 1992 book What Was the First Rock 'n' Roll Record?, identifying it among the precursors of rock and roll.[46]

"Boogie Chillen'" has inspired several songs, beginning in 1953, when Junior Parker recorded his interpretation titled "Feelin' Good".[47] It became Parker's first hit for Sun Records and was subsequently recorded by James Cotton in 1967 and by Magic Sam as "I Feel So Good (I Wanna Boogie)" for his influential 1967 album West Side Soul.[4] A version by Slim Harpo, titled "Boogie Chillun", appeared on his 1970 album Slim Harpo Knew the Blues using a similar arrangement to his 1966 hit "Shake Your Hips".[48]

Other songs that borrow from "Boogie Chillen'" or "Boogie Chillen' No. 2", either directly or indirectly, include the radio hits "On the Road Again" by Canned Heat in 1968, "Spirit in the Sky" by Norman Greenbaum in 1970, and "La Grange" by ZZ Top in 1973.[4][49]

Copyright issues

In 1991, Bernie Besman, as the song's publisher, La Cienega Music, brought legal action against ZZ Top for copyright infringement for their song "La Grange".[36] Writer Timothy English notes that of the various Hooker recordings of "Boogie Chillen'", the one released in 1971 with Canned Heat "has the most elements in common with 'La Grange', including the guitar pattern and the 'howl, howl, howl' vocal line".[50] The case wound its way through the American legal system (including an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court).[51] When the ruling did not favor the publisher, the U.S. Congress was persuaded to amend the Copyright Act in 1998 to protect many songs recorded before 1978 from entering the public domain.[52] ZZ Top settled out of court in 1997,[52] but Hooker again gained no financial reward from his song—Besman had obtained Hooker's rights to the song years earlier.[51] However, Gioia noted, "Nonetheless, his [John Lee Hooker's 1948] spontaneous performance in a recording studio had led to a substantial change in U.S. intellectual property law".[51]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Several sources list the recording date as November 1948,[2][3] which is the date Murray uses for the record release by Modern Records.[1]

- ↑ Both spellings have appeared on Hooker's original singles.

- ↑ Besman later claimed that he suggested that Hooker record a boogie and played a few bars on the piano; Hooker denied that he ever heard Besman play piano or remembered a piano player in the studio.[20]

- ↑ Besman later called these figures "a crock of shit", but admitted "everybody in the record business was crooked".[31]

- ↑ Canned Heat member Alan Wilson, who played harmonica on "Boogie Chillen' No. 2", died before the Hooker 'n Heat album cover photo was taken. His image appears as a portrait on the wall to the right of the window.

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Murray 2002, p. 118.

- ↑ Gioia 2008, p. 237.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sax 1991, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Koda, Cub. "John Lee Hooker: Boogie Chillen' – Song review". AllMusic. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Palmer 1981, p. 243.

- 1 2 3 Dahl 1996, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Murray 2002, p. 90.

- 1 2 Gioia 2008, p. 241.

- ↑ Gioia 2008, p. 244.

- ↑ Gioia 2008, pp. 242–243.

- ↑ Obrecht 2000, p. 427.

- ↑ Obrecht 2000, pp. 406, 426–427.

- ↑ Palmer 1981, p. 243–244.

- ↑ Murray 2002, p. 129.

- ↑ Gioia 2008, p. 238.

- 1 2 3 4 Herzhaft 1992, p. 440.

- ↑ "Mama Don't Allow – Song search results". AllMusic. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Cow Cow Davenport: Boogie No. 3". AllMusic. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ↑ Murray 2002, p. 131.

- 1 2 Murray 2002, p. 127.

- ↑ Kostelanetz & King 2005, p. 100.

- 1 2 Carlson 2005, p. 138.

- ↑ Murray 2002, p. 128.

- 1 2 Murray 2002, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Gioia 2008, p. 245.

- ↑ Sullivan 2013, p. 609.

- ↑ Whitburn 1988, p. 194.

- ↑ Whitburn 1988, p. 597.

- ↑ Fancourt 1988, p. 1.

- ↑ Shadwick 2001, p. 303.

- ↑ Murray 2002, p. 135.

- ↑ Gordon 2002, p. 101.

- ↑ Gioia 2001, p. 245.

- 1 2 3 4 Murray 2002, pp. 133–135.

- ↑ Murray 2002, p. 134.

- 1 2 English 2007, p. 52.

- ↑ Murray 2002, p. 133.

- ↑ Murray 2002, p. 131 fn.

- ↑ Boogie Chillun (Single label). John Lee Hooker. Vee-Jay Records. 1959. VJ 319.

- ↑ Unterberger 1996, p. 117.

- 1 2 Planer, Lindsay. "Hooker 'n Heat (Infinite Boogie) – Album review". AllMusic. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ O'Neal, Jim (November 10, 2016). "1985 Hall of Fame Inductees: Boogie Chillen – John Lee Hooker (Modern, 1948)". The Blues Foundation. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Grammy Hall of Fame Awards – Past Recipients". Grammy.org. 1999. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ "500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. 1995. Archived from the original on May 2, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Complete National Recording Registry Listing". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ↑ Dawson & Propes 1992, eBook.

- ↑ Palmer 1981, p. 244.

- ↑ "Slim Harpo Knew the Blues – Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ↑ Carson 2006, p. 167.

- ↑ English 2007, pp. 52–53.

- 1 2 3 Gioia 2008, p. 251.

- 1 2 English 2007, p. 53.

References

- Carlson, Lenny (2006). "Boogie Chillen'". In Komara, Edward. Encyclopedia of the Blues. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92699-7.

- Carson, David A. (2006). Grit, Noise, and Revolution: The Birth of Detroit Rock 'n' Roll. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-03190-0.

- Dahl, Bill (1996). "John Lee Hooker". In Erlewine, Michael. All Music Guide to the Blues. San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books. ISBN 0-87930-424-3.

- Dawson, Jim; Propes, Steve (1992). What Was the First Rock 'n' Roll Record?. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-12939-0.

- English, Tim (2007). Sounds Like Teen Spirit: Stolen Melodies, Ripped-Off Riffs, and the Secret History of Rock and Roll. iUniverse Star. ISBN 978-1-58348-023-6.

- Fancourt, Leslie (1988). John Lee Hooker: Boogie Chillen (CD notes). John Lee Hooker. Copenhagen, Denmark: Official Record. 86 029.

- Gioia, Ted (2008). Delta Blues (Norton Paperback 2009 ed.). New York City: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-33750-1.

- Gordon, Robert (2002). Can't Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters. New York City: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-32849-9.

- Herzhaft, Gerard (1992). "Boogie Chillen". Encyclopedia of the Blues. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-252-8.

- Kostelanetz, Richard; King, B.B. (2005). The B.B. King Reader: Six Decades of Commentary. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-0-634-09927-4.

- Mandel, Howard, ed. (2005). The Billboard Illustrated Encyclopedia of Jazz & Blues. New York City: Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-8266-0.

- Murray, Charles Shaar (2002). Boogie Man: The Adventures of John Lee Hooker in the American Twentieth Century. New York City: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-27006-3.

- Obrecht, Jas, ed. (2000). Rollin' and Tumblin': The Postwar Blues Guitarists. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-613-7.

- Palmer, Robert (1982). Deep Blues. New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-006223-8.

- Sax, Dave (1991). The Legendary Modern Recordings 1948–1954 (CD notes). John Lee Hooker. Flair Records/Virgin Records. 7243 8 39658 2 3.

- Shadwick, Keith (2007). "John Lee Hooker". The Encyclopedia of Jazz & Blues. London: Quantum Publishing. ISBN 978-0-681-08644-9.

- Schleimer, Joseph D. (February 1998). "Flaws in the 'La Cienega Fix'?: How New Legislation Affects Pre-1972 Recorded Songs". Entertainment Law & Finance. Leader Publications. XIII (11). Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- Sullivan, Steve (2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8295-9.

- Unterberger, Richie (1996). "John Lee Hooker – Hooker & Heat". In Erlewine, Michael. All Music Guide to the Blues. San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books. ISBN 0-87930-424-3.

- Whitburn, Joel (1988). Top R&B Singles 1942–1988. Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research. ISBN 0-89820-068-7.