Bone morphogenetic protein

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are a group of growth factors also known as cytokines and as metabologens.[1] Originally discovered by their ability to induce the formation of bone and cartilage, BMPs are now considered to constitute a group of pivotal morphogenetic signals, orchestrating tissue architecture throughout the body.[2] The important functioning of BMP signals in physiology is emphasized by the multitude of roles for dysregulated BMP signalling in pathological processes. Cancerous disease often involves misregulation of the BMP signalling system. Absence of BMP signalling is, for instance, an important factor in the progression of colon cancer,[3] and conversely, overactivation of BMP signalling following reflux-induced esophagitis provokes Barrett's esophagus and is thus instrumental in the development of adenocarcinoma in the proximal portion of the gastrointestinal tract.[4]

Recombinant human BMPs (rhBMPs) are used in orthopedic applications such as spinal fusions, nonunions and oral surgery. rhBMP-2 and rhBMP-7 are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for some uses. rhBMP-2 causes more overgrown bone than any other BMPs and is widely used off-label.

Medical uses

BMPs for clinical use are produced using recombinant DNA technology (recombinant human BMPs; rhBMPs).

rhBMPs are used in oral surgeries.[5][6][7] BMP-7 has also recently found use in the treatment of chronic kidney disease (CKD). BMP-7 has been shown in murine animal models to reverse the loss of glomeruli due to sclerosis. Curis has been in the forefront of developing BMP-7 for this use. In 2002, Curis licensed BMP-7 to Ortho Biotech Products, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson.

Off-label use

Although rhBMP-2 and rhBMP-7 are used in the treatment of a variety of bone-related conditions including spinal fusions and nonunions, the risks of this off-label treatment are not understood.[8] While rhBMPs are approved for specific applications (spinal lumbar fusions with an anterior approach and tibia nonunions), up to 85% of all BMP usage is off-label.[8] rhBMP-2 is used extensively in other lumbar spinal fusion techniques (e.g., using a posterior approach, anterior or posterior cervical fusions[8]).

Alternative to autograft in long bone nonunions

In 2001, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved rhBMP-7 (a.k.a. OP-1; Stryker Biotech) for a humanitarian device exemption as an alternative to autograft in long bone nonunions.[8] In 2004, the humanitarian device exemption was extended as an alternative to autograft for posterolateral fusion.[8] In 2002, rhBMP-2 (Infuse; Medtronic) was approved for anterior lumbar interbody fusions (ALIFs) with a lumbar fusion device.[8] In 2008 it was approved to repair posterolateral lumbar pseudarthrosis, open tibia shaft fractures with intramedullary nail fixation.[8] In these products, BMPs are delivered to the site of the fracture by being incorporated into a bone implant, and released gradually to allow bone formation, as the growth stimulation by BMPs must be localized and sustained for some weeks. The BMPs are eluted through a purified collagen matrix which is implanted in the site of the fracture.[9] rhBMP-2 helps grow bone better than any other rhBMP so it is much more widely used clinically.[9] There is "little debate or controversy" about the effectiveness of rhBMP-2 to grow bone to achieve spinal fusions,[9] and Medtronic generates $700 million in annual sales from their product.[10]

Contraindications

Bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP) should not be routinely used in any type of anterior cervical spine fusion, such as with anterior cervical discectomy and fusion.[11] There are reports of this therapy causing swelling of soft tissue which in turn can cause life-threatening complications due to difficulty swallowing and pressure on the respiratory tract.[11]

Function

BMPs interact with specific receptors on the cell surface, referred to as bone morphogenetic protein receptors (BMPRs).

Signal transduction through BMPRs results in mobilization of members of the SMAD family of proteins. The signaling pathways involving BMPs, BMPRs and SMADs are important in the development of the heart, central nervous system, and cartilage, as well as post-natal bone development.

They have an important role during embryonic development on the embryonic patterning and early skeletal formation. As such, disruption of BMP signaling can affect the body plan of the developing embryo. For example, BMP4 and its inhibitors noggin and chordin help regulate polarity of the embryo (i.e. back to front patterning). Specifically BMP-4 and its inhibitors play a major role in neurulation and the development of the neural plate. BMP-4 signals ectoderm cells to develop into skin cells, but the secretion of inhibitors by the underlying mesoderm blocks the action of BMP-4 to allow the ectoderm to continue on its normal course of neural cell development.

As a member of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily, BMP signaling regulates a variety of embryonic patterning during fetal and embryonic development. For example, BMP signaling controls the early formation of the Mullerian duct (MD) which is a tubular structure in early embryonic developmental stage and eventually becomes female reproductive tracts. Chemical inhibiting BMP signals in chicken embryo caused a disruption of MD invagination and blocked the epithelial thickening of the MD-forming region, indicating that the BMP signals play a role in early MD development.[12] Moreover, BMP signaling is involved in the formation of foregut and hindgut,[13] intestinal villus patterning, and endocardial differentiation. Villi contribute to increase the effective absorption of nutrients by extending the surface area in small intestine. Gain or lose function of BMP signaling altered the patterning of clusters and emergence of villi in mouse intestinal model.[14] BMP signal derived from myocardium is also involved in endocardial differentiation during heart development. Inhibited BMP signal in zebrafish embryonic model caused strong reduction of endocardial differentiation, but only had little effect in myocardial development.[15] In addition, Notch-Wnt-Bmp crosstalk is required for radial patterning during mouse cochlea development via antagonizing manner.[16]

Mutations in BMPs and their inhibitors (such as sclerostin) are associated with a number of human disorders which affect the skeleton.

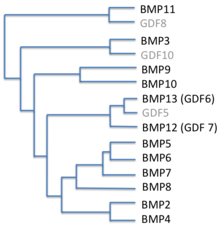

Several BMPs are also named 'cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins' (CDMPs), while others are referred to as 'growth differentiation factors' (GDFs).

Types

Originally, seven such proteins were discovered. Of these, six (BMP2 through BMP7) belong to the Transforming growth factor beta superfamily of proteins. BMP1 is a metalloprotease. Since then, thirteen more BMPs have been discovered, bringing the total to twenty.[9]

| BMP | Known functions | Gene Locus |

|---|---|---|

| BMP1 | *BMP1 does not belong to the TGF-β family of proteins. It is a metalloprotease that acts on procollagen I, II, and III. It is involved in cartilage development. | Chromosome: 8; Location: 8p21 |

| BMP2 | Acts as a disulfide-linked homodimer and induces bone and cartilage formation. It is a candidate as a retinoid mediator. Plays a key role in osteoblast differentiation. | Chromosome: 20; Location: 20p12 |

| BMP3 | Induces bone formation. | Chromosome: 14; Location: 14p22 |

| BMP4 | Regulates the formation of teeth, limbs and bone from mesoderm. It also plays a role in fracture repair, epidermis formation, dorsal-ventral axis formation, and ovarian follical development. | Chromosome: 14; Location: 14q22-q23 |

| BMP5 | Performs functions in cartilage development. | Chromosome: 6; Location: 6p12.1 |

| BMP6 | Plays a role in joint integrity in adults. Controls iron homeostasis via regulation of hepcidin. | Chromosome: 6; Location: 6p12.1 |

| BMP7 | Plays a key role in osteoblast differentiation. It also induces the production of SMAD1. Also key in renal development and repair. | Chromosome: 20; Location: 20q13 |

| BMP8a | Involved in bone and cartilage development. | Chromosome: 1; Location: 1p35–p32 |

| BMP8b | Expressed in the hippocampus. | Chromosome: 1; Location: 1p35–p32 |

| BMP10 | May play a role in the trabeculation of the embryonic heart. | Chromosome: 2; Location: 2p14 |

| BMP11 | Controls anterior-posterior patterning. | Chromosome: 12; Location: 12p |

| BMP15 | May play a role in oocyte and follicular development. | Chromosome: X; Location: Xp11.2 |

History

From the time of Hippocrates it has been known that bone has considerable potential for regeneration and repair. Nicholas Senn, a surgeon at Rush Medical College in Chicago, described the utility of antiseptic decalcified bone implants in the treatment of osteomyelitis and certain bone deformities.[18] Pierre Lacroix proposed that there might be a hypothetical substance, osteogenin, that might initiate bone growth.[19]

The biological basis of bone morphogenesis was shown by Marshall R. Urist. Urist made the key discovery that demineralized, lyophilized segments of bone induced new bone formation when implanted in muscle pouches in rabbits. This discovery was published in 1965 by Urist in Science.[20] Urist proposed the name "Bone Morphogenetic Protein" in the scientific literature in the Journal of Dental Research in 1971.[21]

Bone induction is a sequential multistep cascade. The key steps in this cascade are chemotaxis, mitosis, and differentiation. Early studies by Hari Reddi unraveled the sequence of events involved in bone matrix-induced bone morphogenesis.[22] On the basis of the above work, it seemed likely that morphogens were present in the bone matrix. Using a battery of bioassays for bone formation, a systematic study was undertaken to isolate and purify putative bone morphogenetic proteins.

A major stumbling block to purification was the insolubility of demineralized bone matrix. To overcome this hurdle, Hari Reddi and Kuber Sampath used dissociative extractants, such as 4M guanidine HCL, 8M urea, or 1% SDS.[23] The soluble extract alone or the insoluble residues alone were incapable of new bone induction. This work suggested that the optimal osteogenic activity requires a synergy between soluble extract and the insoluble collagenous substratum. It not only represented a significant advance toward the final purification of bone morphogenetic proteins by the Reddi laboratory,[24][25] but ultimately also enabled the cloning of BMPs by John Wozney and colleagues at Genetics Institute.[26]

Society

Costs

At between US$6000 and $10,000 for a typical treatment, BMPs can be costly compared with other techniques such as bone grafting. However, this cost is often far less than the costs required with orthopaedic revision in multiple surgeries.

While there is little debate that rhBMPs are successful clinically,[9] there is controversy about their use. It is common for orthopedic surgeons to be paid for their contribution to the development of a new product,[27][28] but some of the surgeons responsible for the original Medtronic-supported studies on the efficacy of rhBMP-2 have been accused of bias and conflict of interest.[29] For example, one surgeon, a lead author on four of these research papers, did not disclose any financial ties while with the company on three of the papers;[30] he was paid over $4 million by Medtronic.[30] In another study, the lead author did not disclose any financial ties to Medtronic; he was paid at least $11 million by the company.[30] In a series of 12 publications, the median financial ties of the authors to Medtronic were $12–16 million.[31] In those studies that had more than 20 and 100 patients, one or more authors had financial ties of $1 million and $10 million, respectively.[31] Early clinical trials using rhBMP-2 underreported adverse events associated with treatment. In the 13 original industry-sponsored publications related to safety, there were zero adverse events in 780 patients.[31] It has since been revealed that potential complications can arise from the use including implant displacement, subsidence, infection, urogenital events, and retrograde ejaculation.[30][31]

Based on a study conducted by the Department of Family Medicine at the Oregon Health and Science University the use of BMP increased rapidly, from 5.5% of fusion cases in 2003 to 28.1% of fusion cases in 2008. BMP use was greater among patients with previous surgery and among those having complex fusion procedures (combined anterior and posterior approach, or greater than 2 disc levels). Major medical complications, wound complications, and 30-day rehospitalization rates were nearly identical with or without BMP. Reoperation rates were also very similar, even after stratifying by previous surgery or surgical complexity, and after adjusting for demographic and clinical features. On average, adjusted hospital charges for operations involving BMP were about $15,000 more than hospital charges for fusions without BMP, though reimbursement under Medicare's Diagnosis-Related Group system averaged only about $850 more. Significantly fewer patients receiving BMP were discharged to a skilled nursing facility.[32]

References

- ↑ Reddi AH, Reddi A (2009). "Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs): from morphogens to metabologens". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 20 (5-6): 341–2. PMID 19900831. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.015.

- ↑ Bleuming SA, He XC, Kodach LL, Hardwick JC, Koopman FA, Ten Kate FJ, van Deventer SJ, Hommes DW, Peppelenbosch MP, Offerhaus GJ, Li L, van den Brink GR (Sep 2007). "Bone morphogenetic protein signaling suppresses tumorigenesis at gastric epithelial transition zones in mice". Cancer Research. 67 (17): 8149–55. PMID 17804727. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4659.

- ↑ Kodach LL, Wiercinska E, de Miranda NF, Bleuming SA, Musler AR, Peppelenbosch MP, Dekker E, van den Brink GR, van Noesel CJ, Morreau H, Hommes DW, Ten Dijke P, Offerhaus GJ, Hardwick JC (May 2008). "The bone morphogenetic protein pathway is inactivated in the majority of sporadic colorectal cancers". Gastroenterology. 134 (5): 1332–41. PMID 18471510. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.059.

- ↑ Milano F, van Baal JW, Buttar NS, Rygiel AM, de Kort F, DeMars CJ, Rosmolen WD, Bergman JJ, VAn Marle J, Wang KK, Peppelenbosch MP, Krishnadath KK (Jun 2007). "Bone morphogenetic protein 4 expressed in esophagitis induces a columnar phenotype in esophageal squamous cells". Gastroenterology. 132 (7): 2412–21. PMID 17570215. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.026.

- ↑ "Medtronic Receives Approval to Market Infuse Bone Graft for Certain Oral Maxillofacial And Dental Regenerative Applications". Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ↑ Wikesjö UM, Qahash M, Huang YH, Xiropaidis A, Polimeni G, Susin C (Aug 2009). "Bone morphogenetic proteins for periodontal and alveolar indications; biological observations - clinical implications". Orthodontics & Craniofacial Research. 12 (3): 263–270. PMID 19627529. doi:10.1111/j.1601-6343.2009.01461.x.

- ↑ Moghadam HG, Urist MR, Sandor GK, Clokie CM (Mar 2001). "Successful mandibular reconstruction using a BMP bioimplant". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 12 (2): 119–127. PMID 11314620. doi:10.1097/00001665-200103000-00005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ong KL, Villarraga ML, Lau E, Carreon LY, Kurtz SM, Glassman SD (Sep 2010). "Off-label use of bone morphogenetic proteins in the United States using administrative data". Spine. 35 (19): 1794–800. PMID 20700081. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e3181ecf6e4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Even J, Eskander M, Kang J (Sep 2012). "Bone morphogenetic protein in spine surgery: current and future uses". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 20 (9): 547–52. PMID 22941797. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-20-09-547.

- ↑ John Fauber (2011-10-22). "Doctors didn't disclose spine product cancer risk in journal". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- 1 2 North American Spine Society (February 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, North American Spine Society, retrieved 25 March 2013, which cites

- Schultz, Daniel G. (July 1, 2008). "Public Health Notifications (Medical Devices) - FDA Public Health Notification: Life-threatening Complications Associated with Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein in Cervical Spine Fusion". fda.gov. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Woo EJ (Oct 2012). "Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: adverse events reported to the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database". The Spine Journal. 12 (10): 894–9. PMID 23098616. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2012.09.052.

- ↑ Yuji and Yoshiko (2016). “Early formation of the Mullerian duct is regulated by sequential actions of BMP/Pax2 and FGF/Lim1 signaling”. The Company of Biologists Ltd/ Development. 143, 3549-3559 doi:10.1242/dev.137067.

- ↑ Mariana et al,. (2017). “Genomic integration of Wnt/β-catenin and BMP/Smad1 signaling coordinates foregut and hindgut transcriptional programs”. The Company of Biologists Ltd/ Development. 144, 1283-1295 doi:10.1242/dev.145789.

- ↑ Katherine et al,. (2016). “Villification in the mouse: Bmp signals control intestinal villus patterning”. The Company of Biologists Ltd/ Development. 143, 427-436 doi:10.1242/dev.130112.

- ↑ Sharina et al,. (2015). “Myocardium and BMP signaling are required for endocardial differentiation”. The Company of Biologists Ltd/ Development. 142, 2304-2315 doi:10.1242/dev.118687.

- ↑ Vidhya et al,. (2016). “Notch-Wnt-Bmp crosstalk regulates radial patterning in the mouse cochlea in a spatiotemporal manner”. The Company of Biologists Ltd/ Development. 143, 4003-4015 doi:10.1242/dev.139469.

- ↑ Ducy P, Karsenty G (2000). "The family of bone morphogenetic proteins". Kidney Int. 57 (6): 2207–14. PMID 10844590. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00081.x.

- ↑ Senn N (1889). "On the healing of aseptic bone cavities by implantation of antiseptic decalcified bone". American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 98 (3): 219–243. doi:10.1097/00000441-188909000-00001.

- ↑ Lacroix P (1945). "Recent investigation on the growth of bone". Nature. 156 (3967): 576. doi:10.1038/156576a0.

- ↑ Urist MR (Nov 1965). "Bone: formation by autoinduction". Science. 150 (3698): 893–899. PMID 5319761. doi:10.1126/science.150.3698.893.

- ↑ Urist MR, Strates, Basil S. (1971). "Bone Morphogenetic Protein". Journal of Dental Research 1971. 50 (6): 1392–1406. doi:10.1177/00220345710500060601.

- ↑ Reddi AH, Huggins C (1972). "Biochemical sequences in the transformation of normal fibroblasts in adolescent rats". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69 (6): 1601–5. PMC 426757

. PMID 4504376. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.6.1601.

. PMID 4504376. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.6.1601. - ↑ Sampath TK, Reddi AH (Dec 1981). "Dissociative extraction and reconstitution of extracellular matrix components involved in local bone differentiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 78 (12): 7599–7603. PMC 349316

. PMID 6950401. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.12.7599.

. PMID 6950401. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.12.7599. - ↑ Sampath TK, Muthukumaran N, Reddi AH (Oct 1987). "Isolation of osteogenin, an extracellular matrix-associated, bone-inductive protein, by heparin affinity chromatography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 84 (20): 7109–7113. PMC 299239

. PMID 3478684. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.20.7109.

. PMID 3478684. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.20.7109. - ↑ Luyten FP, Cunningham NS, Ma S, Muthukumaran N, Hammonds RG, Nevins WB, Woods WI, Reddi AH (Aug 1989). "Purification and partial amino acid sequence of osteogenin, a protein initiating bone differentiation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (23): 13377–13380. PMID 2547759.

- ↑ Wozney JM, Rosen V, Celeste AJ, Mitsock LM, Whitters MJ, Kriz RW, Hewick RM, Wang EA (Dec 1988). "Novel regulators of bone formation: molecular clones and activities". Science. 242 (4885): 1528–1534. PMID 3201241. doi:10.1126/science.3201241.

- ↑ Toi Williams (2012-12-20). "Medtronic Accused Of Editing Product Studies". DC Progressive. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ↑ Rebecca Farbo (2013-01-16). "World-renowned Orthopedic Surgeon Sues Medical Device Company For Breach Of Contract". PR Newswire. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ↑ Susan Perry (2012-10-26). "Report reveals disturbing details of Medtronic’s role in shaping InFuse articles". MinnPost. Retrieved 2013-05-13.

- 1 2 3 4 John Carreyrou & Tom McGinty (2011-06-29). "Medtronic Surgeons Held Back, Study Says". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Weiner BK (Jun 2011). "A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned". The Spine Journal. 11 (6): 471–91. PMID 21729796. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2011.04.023.

- ↑ Spinal Fusion and Bone Morphogenetic Protein

Further reading

- Reddi AH (1997). "Bone morphogenetic proteins: an unconventional approach to isolation of first mammalian morphogens". Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 8 (1): 11–20. PMID 9174660. doi:10.1016/S1359-6101(96)00049-4.

- Bessa PC, Casal M, Reis RL (Jan 2008). "Bone morphogenetic proteins in tissue engineering: the road from the laboratory to the clinic, part I (basic concepts)". Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2 (1): 1–13. PMID 18293427. doi:10.1002/term.63.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bone morphogenetic proteins. |

- BMP: The What and the Who

- BMPedia - the Bone Morphogenetic Protein Wiki

- Bone Morphogenetic Proteins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR (Dec 2004). "Bone morphogenetic proteins". Growth Factors (Chur, Switzerland). 22 (4): 233–241. PMID 15621726. doi:10.1080/08977190412331279890.

- Cheng H, Jiang W, Phillips FM, Haydon RC, Peng Y, Zhou L, Luu HH, An N, Breyer B, Vanichakarn P, Szatkowski JP, Park JY, He TC (Aug 2003). "Osteogenic activity of the fourteen types of human bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs)". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 85–A (8): 1544–52. PMID 12925636. link