Bolivarian diaspora

| Part of Crisis in Bolivarian Venezuela | |

|

Airline passengers leaving Venezuela from Maiquetia Airport. | |

| Date | 1999 – present |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Cause | Social issues, political repression, crime, economic downturn, corruption, censorship and others.[1][2][3] |

| Outcome |

|

The Bolivarian diaspora refers to the voluntary emigration of millions of Venezuelans from their native country during the presidency of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, due to the establishment of their Bolivarian Revolution.[1][2][5] According to Newsweek, the "Bolivarian diaspora is a reversal of fortune on a massive scale" where the "reversal" is meant as a comparison to Venezuela's high immigration rate during the 20th century.[2] Initially, upper class Venezuelans and scholars emigrated during Chávez's tenure, though middle and lower class Venezuelans began to leave as conditions worsened in the country.[6]

Venezuelans were often asked in polls if they desired to leave their native country.[7] In December 2015, over 30% of Venezuelans were planning to permanently leave Venezuela.[8] This number nearly doubled months later in September 2016, with 57% of Venezuelans wanting to leave the country according to Datincorp.[9]

History

In the 20th century, Newsweek explains that, "Venezuela was a haven for immigrants fleeing Old World repression and intolerance".[2]The Wall Street Journal noted that emigration from Venezuela began in 1983 after oil prices collapsed, but stated that according to experts, "the outflow, mainly of professionals, has accelerated sharply under Mr. Chávez's Bolivarian Revolution".[10] Anitza Freitez, head of the Economic and Social Research Institute of Andrés Bello Catholic University provided similar findings stating that though emigration existed in Venezuela, it became more prominent in the timeframe of Chávez's presidency.[11]

First diaspora

In 1998, the year Chávez was first elected, only 14 Venezuelans were granted U.S. asylum. In just 12 months in September 1999, 1,086 Venezuelans were granted asylum according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.[13] Chávez's rhetoric of redistributing wealth to the poor concerned wealthy and middle class Venezuelans causing the first portion of a diaspora fleeing the Bolivarian government.[14]

Following the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt in April 2002 and years of political tension following Chávez's rise to power, a spike in emigration occurred in Venezuela.[15] In a May 2002 cable from the United States Embassy, Caracas to United States agencies expressing astonishment at the number of Venezuelans attempting to enter the United States, stating, "This drain of skilled workers could have a significant impact on Venezuela's future".[16] By June 2002, many Venezuelans who had family or links to other countries emigrated, with many families who had immigrated to Venezuela beginning to leave due to the economic and political instability.[15]

Following the 2006 Venezuelan presidential elections and the re-election of Chávez, visits to emigration websites by Venezuelans dramatically increased, with visits to MeQuieroIr.com increasing from 20,000 users in December 2006 to 30,000 users in January 2007 and a 700% increase in visa applications from Venezuelans at vivaenaustralia.com.[17] In 2009, it was estimated that more than 1 million Venezuelan emigrated since Hugo Chávez became president.[2] Since then, it has been calculated by the Central University of Venezuela that from 1999 to 2014, over 1.5 million Venezuelans, between 4% and 6% of the Venezuela's total population, left the country following the Bolivarian Revolution.[5]

Second diaspora

Academics and business leaders have stated that emigration from Venezuela increased significantly during the final years of Chávez's presidency and especially during the presidency of Nicolás Maduro.[18] This second diasporic episode consisted of lower class Venezuelans who suffered from the economic crisis facing the country, with the same individuals that Chávez attempted to aid seeking to emigrate due to their discontent.[14]

In 2015, it was estimated that approximately 1.8 million Venezuelans had emigrated to other countries according to the PGA Group.[19][20] It has been estimated in the year 2016 alone, over 150,000 Venezuelans emigrated from their native country, with The New York Times stating that it was "the highest in more than a decade, according to scholars studying the exodus".[14] Venezuelans have opted to emigrate through various ways, though image of Venezuelans fleeing the country by sea has also raised symbolic comparisons to the images seen from the Cuban diaspora.[14]

Causes

The analysis of a study by Central University of Venezuela titled Venezuelan Community Abroad. A New Method of Exile by El Universal states that the "Bolivarian diaspora" in Venezuela has been caused by the "deterioration of both the economy and the social fabric, rampant crime, uncertainty and lack of hope for a change in leadership in the near future".[1] The Wall Street Journal stated that many "white-collar Venezuelans have fled the country's high crime rates, soaring inflation and expanding statist controls".[10] According to studies of current and former citizens of Venezuela, reasons for leaving Venezuela included lack of freedom, high levels of insecurity and lack of opportunity in the country.[5][21] Director of Link Consultants, Oscar Hernandez, states that causes for the diaspora include economic issues, though insecurity and legal uncertainties are the main reasons for emigration.[4]

Crime

Tomás Páez, Central University of Venezuela[14]

The high crime rate in Venezuela is one of the main reasons Venezuelans emigrate from the country.[1][10] Some Venezuelan parents encourage their children to leave the country in order to protect them from the insecurities that Venezuelans face.[5] Under Hugo Chávez, the "institution" of Venezuela deteriorated, with political instability, impunity and violent government language increasing.[22] According to Gareth A. Jones and Dennis Rodgers in their book Youth violence in Latin America: Gangs and Juvenile Justice in Perspective, "With the change of political regime in 1999 and the initiation of the Bolivarian Revolution, a period of transformation and political conflict began, marked by a further increase in the number and rate of violent deaths".[23] The Bolivarian Revolution attempted to "destroy what previously existed, the status quo of society" with instability increasing.[22] The Bolivarian government then believed that violence and crime were due to poverty and inequality, though while the government boasted about reducing both poverty and inequality, the murder rate continued to increase in Venezuela.[22] The rise of murders in Venezuela following the Chávez presidency has also been attributed by experts to the corruption of Venezuelan authorities, poor gun control and a poor judiciary system.[24]

The murder rate in Venezuela has increased from 25 per 100,000 in 1999 when Chávez was elected[23] to 82 per 100,000 in 2014[25] while kidnappings grew over twentyfold from the beginning of Chávez's presidency to 2011.[26][27][28]

Economy

Since Hugo Chávez imposed stringent currency controls in 2003 in an attempt to prevent capital flight,[29] there have been a series of currency devaluations, disrupting the economy.[30] Price controls, expropriation, and other government policies have caused severe shortages in Venezuela.[31] By 2015, Venezuela had the world's highest inflation rate with the rate surpassing 100%, becoming the highest in the country's history.[32] Since the initiation of the Bolivarian government's polices, many business owners emigrated from Venezuela with many leaving to countries with growing economies.[1]

Political repression

The Venezuelan Community Abroad. A New Method of Exile study explained how the Bolivarian government "would rather urge those who disagree with the revolution to leave, instead of pausing to think deeply about the damage this diaspora entails to the country".[1] Newsweek states that Chávez "pushed hard against anyone" that did not take part in his movement, with science, business and media professionals emigrating from Venezuela following persecution.[2] As many as 9,000 Venezuelan exiles live in the United States with numbers of exiles rising in the European Union as well.[1] According to the Florida Center for Survivors of Torture, since the 2014–15 Venezuelan protests, the majority of torture victims they had assisted were Venezuelan migrants, with the organization providing psychiatrists, social workers, interpreters, lawyers and doctors for dozens of individuals and their families.[33]

Outcomes

Economy

Entrepreneurs emigrated from Venezuela due to government price controls, extortion by government officials, lack of production inputs and the foreign exchange controls. Accountants and administrators left to countries experiencing economic growth, such as Chile, Mexico, Peru, and the United States, so they may be able to be promoted in their careers.[1]

Education

A large number of those emigrating from Venezuela are educated professionals.[5] According to Iván de la Vega of the Simón Bolívar University, 60% to 80% of students in Venezuela said they want to leave Venezuela and not return under the conditions experienced in 2015.[34]

Educational professionals

In 2014, reports emerged showing a high number of education professionals taking flight from educational positions in Venezuela along with the millions of other Venezuelans that had left the country during the presidency of Hugo Chávez, according to Iván de la Vega, a sociologist at Simón Bolívar University.[35] According to the Association of Professors, the Central University of Venezuela lost more 700 of nearly 4000 faculty members between 2011 and 2015.[36] About 240 faculty members also quit at Simón Bolívar University. The reason for emigration is reportedly due to the high crime rate in Venezuela and inadequate pay from the Venezuelan government.[35][36]

Claudio Bifano, president of the Venezuelan Academy of Physical, Mathematical and Natural Sciences, stated that most of Venezuela's "technology and scientific capacity, built up over half a century" had been lost during Hugo Chávez's presidency. Bifano acknowledges the large funds and scientific staff, but states that the output of those scientists had dropped significantly.[37]

According to El Nacional, the flight of educational professionals resulted in a shortage of teachers in Venezuela with the Director of the Centre for Cultural Research and Education, Mariano Herrera, estimating that there was a shortage of about 40% of teachers for mathematics and science classes. The Venezuelan government sought to curb the shortage of teachers through the Simón Rodríguez Micromission by cutting the graduation requirements of educational professional to 2 years.[38]

College graduates

In a study titled Venezuelan Community Abroad. A New Method of Exile by Thomas Paez, Mercedes Vivas and Juan Rafael Pulido of the Central University of Venezuela, of the more than 1.5 million Venezuelans who had left the country following the Bolivarian Revolution, more than 90% of those who left were college graduates, with 40% holding a Master's degree and 12% having a doctorates and post doctorates.[5][21] The study used official verification of data from outside of Venezuela and surveys from hundreds of former Venezuelans.[5]

Industry

A Latin America Economic System study reported that the emigration of highly skilled laborers aged 25 or older from Venezuela to OECD countries rose 216% between 1990 and 2007.[2]

Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA)

Estimates show that 75% of about 20,000 PDVSA workers who had left the company emigrated to other countries for work.[7] Former oil engineers have started working on oil rigs in the North Sea and in the tar sands of western Canada[2] with Venezuelans in Alberta increasing from 465 in 2001 to 3,860 in 2011.[39] Former PDVSA workers had also assisted a more successful oil industry in neighboring Colombia.[39]

According to El Universal, "thousands of oil engineers and technicians, adding up to hundreds of thousands man hours in training and expertise in the oil industry, which is much more meaningful than the academic degrees of individual members" and that most of PDVSA's former elite staff is now working abroad.[1] Following the exodus of PDVSA professionals, production of Venezuelan oil and innovations decreased while work related injuries increased.[39]

Media and entertainment

Actors, producers, TV presenters, anchormen and women, and journalists have reportedly left following the closing of media outlets by the Venezuelan government and after those sympathetic to the government purchasing media outlets. Their preferred destinations are Colombia, Florida and Spain and with musicians, where they emigrate to depends on their style of music.[1]

Medicine

Low pay and lack of recognition caused physician and medical staff, especially from private facilities, to emigrate from the country following the Venezuelan government's opposition to the traditional 6-year programs and instead supports Cuban authorities in training "community medical doctors". The Venezuelan government allegedly restricted facilities and funding for physician training, which has led to the closing of multiple medical programs.[1] In April 2015, president of the Medical Federation of Venezuela, Douglas León Natera, stated that more than 13,000 doctors amounting to over 50% in the country had emigrated from Venezuela, saying that a shortage of doctors had been created and affected both public and private hospitals.[40]

Statistics

The number of Venezuelans living abroad, according to researcher and sociologist Iván de la Vega of the Economics Department of Simón Boívar University, increased 2,000% from the mid-1990s to 2013, from 50,000 Venezuelans living abroad in the mid-1990s to 1,200,000 abroad by the end of 2013.[41] The median age of Venezuelan emigrants is 32 years of age.[34]

Of Venezuelans who stated they had family abroad, the rate went from 10% in 2004 to nearly 30% in 2014.[3] In 2014, about 10% stated that they were preparing to emigrate from the country.[3] According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, "[b]etween 2003 and 2004, the number of (Venezuelan) refugees doubled from 598 to 1,256, and between 2004 and 2009, the number of Venezuelan refugees was five-fold higher, up to 6,221. By that date, there is also a log of 1,580 Venezuelan applicants for refuge."[11]

Groups affected

Emigrants of the Bolivarian diaspora primarily consist of professionals aged between 18 and 35. The majority of Venezuelans attempting to leave the country are in higher classes of the social structure though some of those in the lowest classes plan on emigrating from Venezuela as well.[3]

Colombian population

In the 1990s, Colombians amounted to 77% of all immigrants in Venezuela, according to Raquel Alvarez, a sociologist at the Universidad de los Andes. By the early-2010s, Colombians who had emigrated to Venezuela became disappointed with Venezuela due to the economic collapse of its economy and discrimination by the Venezuelan government and its supporters. Tens of thousands to possibly 200,000 Colombians had left Venezuela in the few years preceding 2015. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, passports to Colombia increased 150% between March 2014 and March 2015. Repatriation assistance of Colombian-Venezuelans had also reached a record number in the first quarter of 2015. According to Martin Gottwald, the deputy head of the United Nation’s refugee agency in Colombia, many of the 205,000 Colombian refugees that had fled to Venezuela may move back to Colombia. The high influx of Colombians returning to Colombia has worried the Colombian government since they may raise the unemployment rate and cause a strain on public services.[42]

Jewish population

The Jewish population in Venezuela has, according to several community organizations, declined from an estimated 18,000–22,000 in 2000,[43] to approximately 9,000 in 2010.[44] Community leaders cite the economy, and security in general, and a rise in anti-semitic sentiment as three main causes for the decline. Some have accused the Venezuelan government of engaging in and/or supporting action and rhetoric considered anti-semitic.[44][45][46][47][48][49][50] In 2015, it was reported that the community had declined to 7,000 members.[51]

Migrant aid

Organizations and events have been created in order to assist Venezuelan emigrants. A website called MeQuieroIr.com was created by a former public affairs worker for PDVSA that moved to Canada and quickly became popular among Venezuelan emigrants.[7][52][53] In June 2015, the first annual Migration Expo was held in Caracas, with the event offering support groups, study-abroad assistance and help with the emigration process.[54]

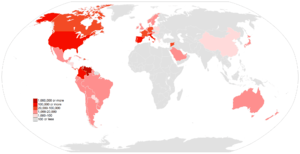

Destinations

The main destinations for Venezuelan emigrants is Colombia, the United States, Canada (esp. for employment in the oil and natural gas industries), Trinidad and Tobago[55] and Europe, though tens of thousands of Venezuelans have also moved to other locations as well.[5][56]

United States

Source: United States Department of Homeland Security[57][58][59]

The United States is one of the main destinations for Venezuelan emigrants.[4][5][11] Between the years 2000 and 2010, the number of individuals living in the U.S. who identified as "Venezuelan" grew 135%, from 91,507 to 215,023.[60] In 2015, it was estimated that about 260,000 Venezuelans had emigrated to the United States.[34] According to researcher Carlos Subero, "the vast majority of Venezuelans trying to migrate enter the country with a nonimmigrant tourist or business visa" with 527,907 Venezuelans staying in the United States with nonimmigrant visas.[3] According to the Latin American and Caribbean Economic System (SELA), in 2007, the percentage Venezuelans 25 years and older in the United States that earned a Ph.D. was 14%, higher than the 9% of Americans having a Ph.D.[11]

Florida

The largest community of Venezuelans in the United States resides in South Florida.[5] Between 2000 and 2012, the number of legal Venezuelan residents in Florida increased from 91,500 to 259,000.[61] In 2015, the Venezuelan Refugee Assistance Act was proposed by Florida congressional delegates with the help of the United States House of Representatives.[61] The proposal would adjust the status of Venezuelans that arrived in the United States before 1 January 2013, only if they were not criminals or involved in political persecution, with such Venezuelans having until 1 January 2019 to apply for adjustment.[61] One chief sponsor, U.S. Representative Carlos Curbelo, stated, "This bill will help those Venezuelan nationals who have made a new home in the United States to remain here if they choose to since it is dangerous to return home".[61]

Latin America and Caribbean

Latin American countries such as Colombia, Mexico, Panama, Chile (known for its economic and political stability) and Argentina are also popular destinations for those emigrating from Venezuela.[18] Venezuelan emigration to Argentina has grown significantly since 2005, rising from 148 annually in 2005 to 3,757 in 2014; over 15,000 Venezuelans emigrated to Argentina from 2004 to 2014, of which 4,781 have obtained permanent residency.[62]

Aruba and Curaçao

The islands of Aruba and Curaçao were once a tourist destination for Venezuelans seeking a vacation. Now the island nations have resorted to sealing their borders from Venezuelans seeking refuge. The islands require Venezuelans to have at least $1,000 in cash on hand before entering the country, with that amount of money being the total of a Venezuelan working a minimum wage job for several years. Patrolling and the deportation of Venezuelans has increased in recent years. Meanwhile, Aruba has designated a stadium to hold Venezuelan illegal immigrants who are facing deportation.[14]

The journey to Curaçao is often a dangerous 60-mile trip, with Venezuelans facing "backbreaking swells, gangs of armed boatmen and coast guard vessels looking to capture migrants and send them home". Venezuelans are smuggled near the shores of the island, dumped overboard and forced to swim to land where they later meet with contacts to set up their new lives. According to the government of Curaçao, common jobs taken by Venezuelans on the islands consist of providing services to tourists, where immigrants will "clean the floors of restaurants, sell trinkets on the street, or even solicit Dutch tourists for sex, forced by the smugglers to pay for their passage by working in a brothel". The Dutch Caribbean Coast Guard estimates that only 5% to 10% of boats carrying illegal Venezuelan immigrants are intercepted.[14]

Brazil

As socioeconomic conditions worsened in Venezuela, many Venezuelans emigrated to the neighboring country of Brazil. Tens of thousands of Venezuelan refugees have traveled through the Amazon basin into Brazil seeking a better life.[14] Some travel by foot into Brazil while others pay over $1,000 to be smuggled into larger cities.[14] In the state of Roraima in Brazil, over 70,000 Venezuelans refugees [63] have moved there over a few months in late-2016 causing resource difficulties in the area.[6] Hundreds of Venezuelan children are now enrolled in schools near Brazil's border with Venezuela.[14]

The Brazilian government has increased military presence on its border with Venezuela to help assist with refugees traversing on its roads and rivers.[14]

Colombia

Following the reopening of the border with Colombia after the Venezuela–Colombia migrant crisis, many Venezuelans emigrated to Colombia.[64] In July 2016, over 200,000 Venezuelans poured into Colombia to purchase goods due to shortages in Venezuela.[65] On 12 August 2016, the Venezuelan government officially reopened its border with Colombia, with thousands of Venezuelans, again, entering Colombia to seek escape from Venezuela's crisis.[65]

Colombia's oil industry has benefited from skilled workers emigrating from Venezuela. However, in late 2016, many unauthorized immigrants have begun to be deported from the country.[64] The Colombian government believes that in the first half of 2017, more than 100,000 Venezuelans emigrated to Colombia.[66] On the days before the 2017 Venezuelan Constitutional Assembly elections, Colombia granted a Special Permit of Permanence option to Venezuelan citizens who entered the country prior to 25 July 2017, with over 22,000 Venezuelans applying for permanent residency in Colombian within the first 24 hours.[67]

Chile

In 2016, Venezuelans emigrated to Chile due to its stable economy and its simple immigration policy. According to the Chilean Department for Foreigners and Migration, the number of Chilean visas for Venezuelans increased from 758 in 2011 to 8,381 in 2016, with over nearly 90% issued as work visas for Venezuelans aged 20 to 35. Since international travel by air is difficult, especially due to the low value of the Venezuelan bolivar, desperate Venezuelans must travel land through dangerous terrain to reach Chile. After arriving, they must start their lives over, with Delio Cubides, executive secretary of the Catholic Chilean Migration Institute stating that most Venezuelan immigrants "are accountants, engineers, teachers, the majority of them very well-educated", though they resort to taking low-paying jobs so they can meet visa requirements and stay in the country.[64][68]

Mexico

Compared to the 2000 Mexican Census, there was an increase from 2,823 Venezuelan Mexicans in 2000 to 10,063 in 2010, a 357% increase of Venezuelan-born individuals living in Mexico.[69] Mexico granted 975 Venezuelans permanent identification cards in the first 5 months of 2014 alone, double the number of Venezuelans granted ID cards altogether in 2013.[18]

Peru

President of Peru, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski introduced Supreme Decree Nº 002-2017-IN, granting Venezuelan nationals in Peru a Temporary Permit of Permanence (PTP), with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights applauding the decree and encouraged other Latin American countries to adopt similar measures to assist Venezuelans. Venezuelan Union in Peru, a non-governmental organization, announced that they would present President Kuczynski's actions to the Norwegian Nobel Committee and nominate him for the Nobel Peace Prize, stating:[71]

| “ | [W]hile other countries build walls, in Peru, bridges are built to bring citizens closer and protect their most elementary fundamental rights, so with overwhelming hope we will present this nomination of President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, not only in search of this award, but also to place in the international debate the abuses of which Latin American migrants are victims in some parts of the world. | ” |

Months after the decree, over 40,000 Venezuelan refugees entered Peru by August 2017.[72]

Trinidad and Tobago

Throughout Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuela's history, Venezuelans have emigrated both legally and illegally due to the country's relatively stable economy, access to United States dollars and close proximity to Eastern Venezuela.[73] Direct flights from Maturin, Caracas and Isla Margarita as well as a ferry service between Guiria to Chaguaramas, Trinidad and Tobago and Tucupita to Cedros, Trinidad and Tobago have been official modes of transport, while illegal routes tend to exist between Venezuela's eastern coast and the Gulf of Paria.[74]

Approximately 14,000 Venezuelans entered Trinidad and Tobago between January 1 and May 10 in 2016 with 43% of these reportedly overstaying their allotted visa period.[73] Venezuelans that remain often seek out employment throughout the island while others, particularly women, enter the sex industry.[75]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Olivares, Francisco (13 September 2014). "Best and brightest for export". El Universal. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Hugo Chavez is Scaring Away Talent". Newsweek. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ten percent of Venezuelans are taking steps for emigrating". El Universal. 16 August 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 "La emigración venezolana a diferencia de otras "se va con un diploma bajo el brazo"". El Impulso. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Maria Delgado, Antonio (28 August 2014). "Venezuela agobiada por la fuga masiva de cerebros". El Nuevo Herald. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- 1 2 LaFranchi, Howard (2 November 2016). "Why time is ripe for US to address Venezuela's mess". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Pitts, Pietro D.; Rosati, Andrew (4 December 2014). "Venezuela’s Oil Industry Exodus Slowing Crude Production: Energy". Bloomberg. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Lee, Brianna (2 December 2015). "Venezuela Elections 2015: Why Venezuelans Are Fleeing The Country". International Business Times. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Margolis, Mac (14 September 2016). "Latin America Has a Different Migration Problem". Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 Gonzalez, Angel; Minaya, Ezequiel (17 October 2011). "Venezuelan Diaspora Booms Under Chávez". Dow Jones & Company Inc. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Pablo Peńaloza, Pedro (13 January 2014). "Number of outgoing Venezuelans on the rise". El Universal. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Casey, Nicholas (5 January 2016). "Arriving in Venezuela and Taking a Selfie, as Many of My Peers Depart". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Tom (16 July 2007). "Venezuelans, fleeing Chavez, seek U.S. safety net". Reuters. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Casey, Nicholas (25 November 2016). "Hungry Venezuelans Flee in Boats to Escape Economic Collapse". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Dateline migration: International". Migration World Magazine. 30 (4/5): 7–13. 2002.

- ↑ "AREPA 14" (PDF). United States Department of State. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "La historia de una familia que abandonó Venezuela". Noticias24. 18 March 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 Symmes Cobb, Julia; Garcia Rawlins, Carlos (15 October 2014). "Economic crisis, political strife drive Venezuela brain-drain". Reuters. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "1,8 millones de venezolanos han emigrado en 10 años". Globovision. 23 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ "PGA Group estima que 1,8 millones de venezolanos han emigrado en 10 años". La Nación. 23 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- 1 2 "El 90% de los venezolanos que se van tienen formación universitaria". El Impulso. 23 August 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Briceño-León, Roberto. "Three phases of homicidal violence in Venezuela". SciELO. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- 1 2 Jones, Gareth A.; Rodgers, Dennis, eds. (2008). Youth violence in Latin America : gangs and juvenile justice in perspective (1st ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9780230600560. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ↑ Rueda, Manuel (6 April 2015). "Venezuelan beauty queen gets carjacked at gunpoint". Fusion. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela Ranks World's Second In Homicides: Report". NBC News. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "SeguridadPúblicayPrivada VenezuelayBolivia" (PDF). Oas.org. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ↑ "Venezuela: Gravísima Crisis de Seguridad Pública by Lexys Rendon". ISSUU.com. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ↑ "Según el Cicpc el 2011 cerró con 1.150 secuestros en todo el país - Sucesos". Eluniversal.com. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ↑ "Venezuela’s currency: The not-so-strong bolívar". The Economist. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Mander, Benedict (10 February 2013). "Venezuelan devaluation sparks panic". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "Venezuela’s economy: Medieval policies". The Economist. 20 August 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ Cristóbal Nagel, Juan (13 July 2015). "Looking Into the Black Box of Venezuela’s Economy". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Fernández, Abel (16 July 2015). "New victims of oppression seeking help at Miami center come from Venezuela". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Zabludovsky, Karla (15 May 2015). "Venezuela’s Lost Generation". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- 1 2 Small Carmona, Andrea. "Poor conditions blamed for Venezuelan scientist exodus". SciDev. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- 1 2 Rueda, Jorge (11 June 2015). "Professors Flee, Higher Education Suffers in Venezuela". Associated Press. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "Capacity building: Architects of South American science" (PDF). Nature. 510: 212. 12 June 2014. doi:10.1038/510209a. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ↑ Montilla K., Andrea (4 July 2014). "Liceístas pasan de grado sin cursar varias materias". El Nacional. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Venezuela’s oil diaspora Brain haemorrhage". The Economist. 19 July 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "León Natera: Más de 13 mil médicos se han ido del país". El Nacional. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Vásquez, Elisa (27 June 2014). "Venezuela’s Emigration Wave Takes Toll on Mental Health". PanAm Post. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Kurmanaev, Anatoly; Medina, Oscar (4 May 2015). "Venezuela’s Poor Neighbors Flee en Masse Years After Arrival". Bloomberg Business. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ Shlomo Papirblat (November 20, 2010). "In Venezuela, remarks like 'Hitler didn't finish the job' are routine". Ha'aretz. Retrieved November 20, 2010. See also Gil Shefler (September 1, 2010). "Jewish community in Venezuela shrinks by half". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- 1 2 Rueda, Jorge (4 December 2007). "Jewish leaders condemn police raid on community center in Venezuela". U-T San Diego. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Hal Weitzman (March 26, 2007). "Venezuelan Jews fear for future". JTA. Archived from the original on November 24, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ↑ Thor Halvorssen Mendoza (August 8, 2005). "Hurricane Hugo". The Weekly Standard. 10 (44). Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ↑ Annual Report 2004: Venezuela. Archived October 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Stephen Roth Institute. Accessed August 11, 2006.

- ↑ Berrios, Jerry. S. Fla. Venezuelans: Chavez incites anti-Semitism. Archived 2008-03-06 at the Wayback Machine. Miami Herald, August 10, 2006.

- ↑ Report: Anti-Semitism on Rise in Venezuela; Chavez Government 'Fosters Hate' Toward Jews and Israel. Press release, Anti-Defamation League, November 6, 2006. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- ↑ The Chavez Regime: Fostering Anti-Semitism and Supporting Radical Islam. Anti-Defamation League, November 6, 2006. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- ↑ "ADL Denounces Anti-Semitic Graffiti Sprayed on Synagogue in Venezuela". Algemeiner Journal. 2 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "¿Quiénes somos?". MeQuieroIr.com. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Weg!". De Redactie. 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Rosati, Andrew (16 June 2015). "Venezuela: Emigration Nation". WLRN-FM. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ http://www.trinidadexpress.com/20160512/news/14000-venezuelans-flock-to-tt

- ↑ "Cada vez más venezolanos quieren vivir en Colombia". La Patilla (in Spanish). 8 October 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ "2004 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics" (PDF). United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "2009 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics" (PDF). United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013". United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "The Hispanic Population: 2010, 2010 Census Briefs" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Durby, Kevin (12 October 2015). "Florida Congressional Representatives Want to Extend Venezuelans Exiles Stays". Sunshine State News. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "Argentina se vuelve destino clave para la emigración venezolana". El Universal. 16 March 2015.

- ↑

- 1 2 3 Woody, Christopher (2 December 2016). "'The tipping point': More and more Venezuelans are uprooting their lives to escape their country's crises". Business Insider. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Venezuelans cross into Colombia after border is reopened". BBC News. 13 August 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ "As Venezuela's economy plummets, mass exodus ensues". PBS NewsHour. 9 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ "Unos 22 mil venezolanos tramitaron en 24 horas permiso especial en Colombia". La Patilla (in Spanish). 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ Fernández, Airam (12 October 2016). "Venezuelans flee to Chile in risky nine-day journey by road and river". Univision. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Estadísticas Históricas de México" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics and Geography. pp. 83, 86. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics and Geography. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "Venezolanos en Perú postularán a presidente Kuczynski a Nobel de la Paz". La Patilla (in Spanish). 16 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ "Peru fears Venezuela headed toward civil war: foreign minister". Reuters. 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- 1 2 http://www.guardian.co.tt/news/2016-05-09/venezuelans-cautious-entering-cedros-icacos

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.tt/news/2016-05-22/venezuelans-flock-tt-supplies

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.tt/news/2016-06-05/venezuelans-taking-tt-jobs