Bois Protat

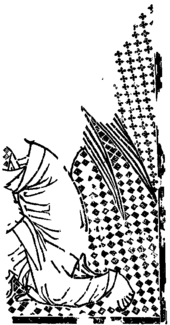

The woodblock fragment Bois Protat ([bwɑ pʁɔta] ("Protat wood[block]"); also Protat block or Protat woodblock, c. 1370–1380) is a fragmentary woodblock for printing, and the images on it are the oldest surviving woodcut images from the Western world. It is cut on both sides, with a scene from Christ's crucifixion on the recto, and a kneeling angel from a presumed Annunciation scene on the verso. The crucifixion scene likely consisted of three or more blocks; the surviving block fragment features Longinus the Roman centurion at the Crucifixion, shown speaking with a banderole, a mediaeval precursor to the modern speech balloon containing his words.

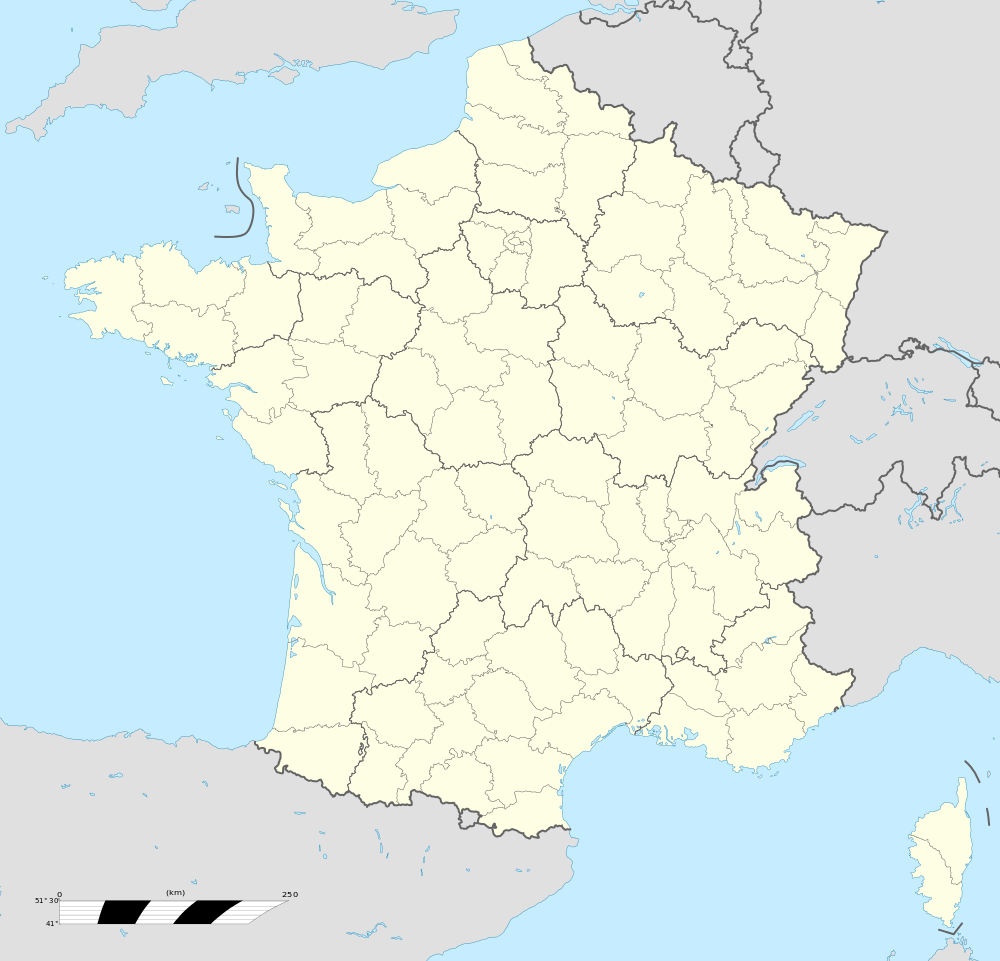

The Bois Protat's name comes from the Mâconnais printer Jules Protat who acquired the block after its discovery in 1898 near La Ferté Abbey in Saône-et-Loire, France, where it was wedged under a stone floor. Because of such poor preservation, only a quarter of the block has survived, and only one side was able to withstand making prints at the time of discovery. It is kept in the Department of Prints and Photographs at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the National Library of France in Paris.

Description

A 600×230×25-millimetre (24×9×1 in)[1] fragment remains of the Bois Protat, a walnut woodblock engraved on both sides for printing on cloth or paper.[2] One side is a fragment of a Crucifixion scene. Part of the cross with the left arm of Christ is visible; to the right two Roman soldiers and a centurion stand speaking. A phylactery, or speech scroll, emanates from the centurion's mouth and contains the Latin text, "Vere filius Dei erat iste" ("This was really the son of God"), as written in the Vulgate translation of Matthew 27:54. On the reverse side remains a kneeling angel, probably part of an Annunciation scene.[3]

Judging from the Crucifixion fragment, coming from a very commonly depicted scene, it is thought that only a quarter to a third of the original block remains. The surface of the complete scene is believed to have been about 100 by 60 centimetres (39 in × 24 in), which is larger than contemporary paper sizes,[lower-alpha 1] indicating it may have been intended for printing on cloth,[5] as was already common with patterns for clothing textiles. It is usually thought that it was intended for printing cloth altar frontals or hangings.[6] It is rare for such a block to be carved with images on both sides,[7] and was likely not intended to be printed using a press, as that would have defaced one side.[8]

Background

Relief printing, in the form of woodblocks, originated in China. The earliest examples were printed on cloth; paper prints followed the invention of paper c. 105 CE. Most printed images were religious Buddhist scenes,[9] and the method was also the method used for texts of all sorts.

The Bois Protat is the earliest surviving example of the 14th-century arrival of woodblock printing in Europe.[10] The technology did not become widespread until the 15th century, when paper became readily available. Prints tended to be religious; they were more affordable to most people than devotional paintings, and often illustrated religious books. Playing cards and other secular prints were also popular. From the mid-15th century woodcuts were combined with Gutenberg's moveable type; particularly in Germany, woodcuts appeared by master artists such as Albrecht Dürer, and the form enjoyed a high level of artistry.[11]

History

The Bois Protat was discovered in 1898[12] in France in a corner of masonry in a house in Laives in the department of Saône-et-Loire, which had been a dependency of the Abbey of La Ferté until the abbey was destroyed in 1793 during the French Revolution.[13] The board suffered from pressure and humidity,[7] as it was wedged under pavement.[14]

After its discovery the block was purchased by Mâconnais printer and collector Jules Protat (1852–1906), and came to be called le bois Protat ("the Protat block").[15] Jules Protat made some test prints on China paper, one of which he exhibited at the 1900 World's Fair in Paris. The block is not in a state to withstand repeated printings, as three-quarters of the original has been lost to damage from humidity and insects; the reverse especially has not held up well,[16] and is not in a condition suitable for making impressions.[17] The curator of prints at the National Library of France Henri Bouchot published a study on the block in 1902 called Un ancêtre de la gravure sur bois ("An Ancestor of Wood Engraving").[18] Though some contested his conclusions, Bouchot dated the work to the 14th century based on technical details such as the style of art, the Uncial script of the centurion's speech, and the costumes and weapons of the centurion and soldiers.[2] No historical impressions (prints) made from the block are known, but other early woodcuts have been attributed to the same artist.[6]

For some time the Bois Protat remained in Protat's family before it was entrusted to Bouchot.[19] In 2001 it was donated to the National Library of France.[20]

Notes

References

- ↑ Bouchot 1902, p. 37; Blum 1940, p. 70.

- 1 2 Blum 1940, p. 70.

- ↑ Bouchot 1902, p. 41.

- ↑ Bouchot 1902, p. 42.

- ↑ Bouchot 1902, pp. 41–42.

- 1 2 Hind 1927, p. 251.

- 1 2 Bouchot 1902, p. 37.

- ↑ Bouchot 1902, p. 4.

- ↑ White 2002, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Ross 2009, p. 2; White 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ White 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ Parshall & Schoch 2005, p. 8.

- ↑ Bouchot 1902, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Cardon 1999, p. 347.

- ↑ Bouchot 1902, p. vii.

- ↑ Bouchot 1902, p. 40.

- ↑ Ross 2009, p. 3.

- ↑ Durrieu 1917, p. 254.

- ↑ Parshall & Schoch 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ Roux 2013, pp. 50, 131.

Works cited

- Blum, André (1940). The Origins of Printing and Engraving. Translated by Harry Miller Lydenberg. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons – via Questia. (Subscription required (help)).

- Bouchot, Henri (1902). Un ancêtre de la gravure sur bois. Étude sur un xylographe taillé en Bourgogne vers 1370 [An ancestor of wood engraving. Study on a woodblock carved in Bourgogne around 1370] (in French). Émile Lévy.

- Cardon, Dominique (1999). "À la découverte d'un métier médiéval. La teinture, l'impression et la peinture des tentures et des tissus d'ameublement dans l'Arte della lana". Mélanges de l'École française de Rome, Moyen-Age, Temps modernes (in French). 111 (1): 323–356. doi:10.3406/mefr.1999.3697 – via Persée.

- Durrieu, Paul (1917). "Les origines de la gravure (deuxième et dernier article)" [The origins of engraving (second and last article)]. Journal des savants (in French). 15 (6): 251–264 – via Persée.

- Hind, A. M. (November 1927). "Early Prints: France's Contribution". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 51 (296): 251–252. JSTOR 863393.

- Parshall, Peter W.; Schoch, Rainer, eds. (2005). Origins of European Printmaking: Fifteenth-century Woodcuts and Their Public. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-300-11339-6.

- Ross, John (2009). Complete Printmaker. Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-3509-9.

- Roux, Maïté (2013). Les dations aux biliothèques (PDF) (Mémoire de fin d'étude du diplôme de conservateur) (in French). University of Lyon. Archived from the original on 2015-05-21.

- White, Lucy Mueller (2002). Printmaking as Therapy: Frameworks for Freedom. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84642-335-2.

External links

-

Media related to Bois Protat at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bois Protat at Wikimedia Commons - The Bois Protat on display (in French)