Paralithodes platypus

| Paralithodes platypus | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Family: | Lithodidae |

| Genus: | Paralithodes |

| Species: | P. platypus |

| Binomial name | |

| Paralithodes platypus (Brandt, 1850) | |

Paralithodes platypus, the blue king crab, is a species of king crab which lives near St. Matthew Island, the Pribilof Islands, and the Diomede Islands, Alaska, with further populations along the coasts of Japan and Russia.[2] Blue king crabs from the Pribilof Islands are the largest of all the king crabs, sometimes exceeding 18 pounds (8.2 kg) in weight.[3]

Fisheries

Commercial blue king crab harvest around the eastern Bering Sea began in the mid-1960s and peaked in 1981 with a catch of 13,228,000 pounds (6,000 t).[4][5] The Pribilof Island harvest by the United States peaked in 1980 at 10,935,000 lb (4,960 t) and was closed in 1988 due to population decline,[6] then again in 1999 after being opened for three years.[7] The St. Matthew fishery peaked in 1983 with 9,453,500 lb (4,288.0 t) but experienced a similar decline and was closed in 1999. It was opened in 2009, and was featured on the television show Deadliest Catch. The St. Matthew stock is rebuilding but the fishery remains closed, while the Pribilof stock has not drastically improved.[5][7] Diomede blue king crabs have never been harvested commercially, but support a subsistence fishery for the Native Village of Diomede, Alaska, population 170.

Colder water slows the rate of crab growth and crabs at northern latitudes are often smaller than more southern crabs. Commercial harvest of blue king crabs at the Pribilof Islands is limited to males with a carapace width (CW) over 6.5 inches (170 mm) and St. Matthew Island is limited to crabs with CW greater than 5.5 in (140 mm),[6][8] corresponding to crabs over 4.7 in (120 mm) carapace length (CL).[9] Diomede blue king crabs are similar in size to St. Matthew Island crabs.

Distribution

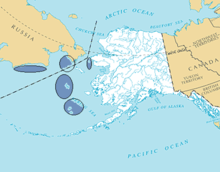

Blue king crabs can be found in the Bering Sea in relatively small abundances compared to red king crabs. The main populations near Alaska are found near the Diomede Islands, Point Hope, St. Matthew Island, and the Pribilof Islands.[1] Additionally, populations exist in the Norton Sound all the way to the St. Lawrence Islands.[10] There are smaller populations located off the eastern coast of Asia, near northern Japan and Siberia.[10] Blue king crabs have a more northerly distribution compared to red king crabs, which is due to the colder waters of the northern Bering Sea being suitable for blue king crabs to survive.[11] The unique population locations of the blue king crab are a result from glacial interactions with the water temperature of the Bering Sea. A period of increased temperature limited the spread of cold-water species, pushing the species further northward into the depths of the Bering Sea.[1] Not only did blue king crabs retreat to the northern stretches of the Bering Sea, but they also had a possible population shrinkage due to glacial epochs.[10]

Migration

Female blue king crabs migrate seasonally from depths of 400–600 feet (120–180 m) in winter to shallow depths of 20–35 ft (6.1–10.7 m) for females with eggs and 150–250 ft (46–76 m) for females without eggs.[12] The average depth for male crabs of commercial size is 230 ft (70 m),[13] although crabs can commonly be caught at shallower depths in winter.

Reproduction

Pribilof Island blue king crabs mate and produce eggs in late March to early May.[14] Females generally brood their eggs externally for 12–14 months.[13][15][16] Since blue king crabs need more than a year to brood their eggs, they miss a breeding cycle just before the larvae hatch and only produce eggs every other year, although first-time breeders can often produce eggs in subsequent years. Females release larvae around the middle of April in the Pribilof Islands,[15] while those held at warmer temperatures in the laboratory may release larvae as early as February.[16]

Female blue king crabs in the Pribilof Islands grow to the largest size before they are reproductively mature. About 50% of crabs are mature at 5 in (130 mm) CL.[16] St. Matthew Island females can become sexually mature at 3 in (76 mm) CL[17] and Diomede crabs are similar. Larger female crabs from the Pribilof Islands have the highest fecundity, producing 162,360 eggs or 110,033 larvae per crab.[16] The reduction in fecundity is about 33% between the egg and larval stages.[14] In Japan, an average of 120,000 larvae were released from each blue king crab.[18] Diomede blue king crabs release an average of 60,000 larvae per female.

Environmental variables, such as tides, temperature, salinity, light, phytoplankton blooms, and predation, are seasonally pulsed and likely serve as cues for larval release.[19][20] Release of larvae over a longer period may serve to give the female a larger window for larvae to correspond with any favorable environmental conditions that may exist, also known as “bet-hedging”.[21] In the laboratory, Pribilof larvae hatch over the course of about one month,[22] and Diomede larvae hatch over the course of 2–3 weeks. These differences may be due to water temperature in the laboratory, which has a clear effect on embryonic and larval development, and is probably slightly different from hatch timing in a natural environment.

References

- 1 2 3 "Blue King Crab Species Profie". Alaska Department of Fish and Game. State of Alaska. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Vining, I.; S. F. Blau; et al. (2001). "Evaluating changes in spatial distribution of blue king crab near St. Matthew Island". In G. H. Kruse; N. Bez; A. Booth; M. W. Dorn; S. Hills; R. N. Lipcius; D. Pelletier; C. Roy; S. J. Smith; D. Witherell. Spatial processes and management of marine populations. University of Alaska Sea Grant College Program Report. pp. 327–348. ISBN 978-1-56612-068-5.

- ↑ "King Crab 101". Fisherman's Express. 2000.

- ↑ Zheng, J.; G. H. Kruse (2000). "Recruitment patterns of Alaskan crabs in relation to decadal shifts in climate and physical oceanography" (PDF). ICES Journal of Marine Science. 57 (2): 438–451. doi:10.1006/jmsc.1999.0521.

- 1 2 Bowers, F. R.; M. Schwenzfeier; et al. (2008). "Annual management report for the commercial and subsistence shellfish fisheries of the Aleutian Islands, Bering Sea and the westward region's shellfish observer program, 2007-2008" (PDF). Alaska Department of Fish and Game; Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries. 269.

- 1 2 Zheng, J.; M. C. Murphy; et al. (1997). "Application of a catch-survey analysis to blue king crab stocks near Pribilof and St. Matthew Islands" (PDF). Alaska Fishery Research Bulletin. 4 (1): 62–74.

- 1 2 Chilton, E. A.; C. E. Armistead; et al. (2008). "The 2008 Eastern Bering Sea Continental Shelf Bottom Trawl Survey: Results for Commercial Crab Species" (PDF). NOAA Fisheries Report.

- ↑ Alaska Department of Fish and Game (1998). "1998-1999 commercial shellfish fishing regulations". Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Juneau, Alaska. 163.

- ↑ Stevens, B. G.; J. A. Haaga; et al. (2001), Report to Industry on the 2001 Eastern Bering Sea Crab Survey. NMFS, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Kodiak, Alaska (PDF), University of Alaska Sea Grant College Program Report, 62

- 1 2 3 Stevens, Bradley (2014). King Crabs of the World (1 ed.). CRC Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4398-5542-3. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Armstrong, David (1981). "Distribution & Abundance of decapod larvae in the southeastern Bering Sea with emphasis on commercial species" (PDF). p. 548. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Pereladov, M. V.; D. M. Miljutin; et al. (2002). "Population structure of blue king crab (Paralithodes platypus) in the northwestern Bering Sea". In A. J. Paul; E. G. Dawe; R. Elner; G. S. Jamieson; G. H. Kruse; R. S. Otto; B. Sainte-Marie; T. C. Shirley; D. Woodby. Crabs in cold water regions: Biology, management and economics. pp. 511–520. ISBN 1-56612-077-2.

- 1 2 North Pacific Fishery Research Council (2005). "Essential Fish Habitat Assessment Report for the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands King and Tanner Crabs" (PDF). NOAA Fisheries Report.

- 1 2 Somerton, D. A.; R. A. MacIntosh (1985). "Reproductive biology of the female blue king crab Paralithodes platypus near the Pribilof Islands, Alaska". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 5 (3): 365–376. JSTOR 1547908. doi:10.2307/1547908.

- 1 2 Jensen, G. C.; D. A. Armstrong (1989). "Biennial reproductive cycle of blue king crab, Paralithodes platypus, at the Pribilof Islands, Alaska and comparison to a congener Paralithodes camtschatica". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 46 (6): 932–940. doi:10.1139/f89-120.

- 1 2 3 4 Stevens, B. G.; K. M. Swiney (2006). "Timing and duration of larval hatching for blue king crab Paralithodes platypus Brandt, 1850 held in the laboratory". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 26 (4): 495–502. doi:10.1651/S-2677.1.

- ↑ Somerton, D. A.; R. A. MacIntosh (1983). "The size at sexual maturity of blue king crab, Paralithodes platypus, in Alaska". Fishery Bulletin. 81 (3): 621–628.

- ↑ Sasakawa, Y. (1973). "Studies on blue king crab resources in the western Bering Sea — III: Ovarian weight, carried egg number and diameter". Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries. 41: 941–944.

- ↑ Shirley, T. C.; S. M. Shirley (1989). "Temperature and salinity tolerances and preferences of red king crab larvae". Marine Behaviour and Physiology. 16 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1080/10236248909378738.

- ↑ Morgan, S. G. (1995). "The timing of larval release". In L. R. McEdward. Ecology of marine invertebrate larvae. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. pp. 157–191. ISBN 978-0-8493-8046-4.

- ↑ Slatkin, M. (1974). "Hedging one's evolutionary bets". Nature. 250 (5469): 704–705. doi:10.1038/250704b0.

- ↑ Stevens, B. G. (2006). "Embryo development and morphometry in the blue king crab Paralithodes platypus studied by using image and cluster analysis" (PDF). Journal of Shellfish Research. 25 (2): 569–576. doi:10.2983/0730-8000(2006)25[569:EDAMIT]2.0.CO;2.