Blue baby syndrome

| Blue baby syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

|

A cyanotic newborn, or "blue baby". Note the blue coloration of the fingertips. | |

| Classification and external resources |

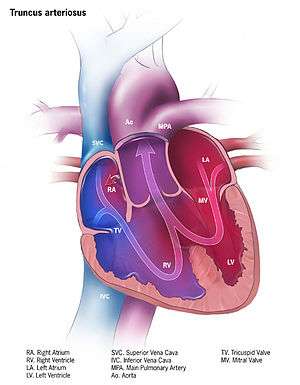

Blue baby syndrome refers to at least two situations that lead to cyanosis in infants: cyanotic heart disease and methemoglobinemia. The most common cyanotic heart defects include transposition of the great vessels, tetralogy of Fallot, persistent truncus arteriosus, tricuspid atresia and total anomalous pulmonary venous return.

Causes

A number of cardiovascular defects may lead to Blue baby syndrome, including the following:

Tetralogy of Fallot

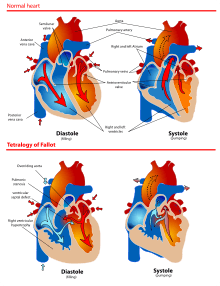

The most common cause of blue baby syndrome, and the one which was the subject of the classic "blue baby operation" developed at Johns Hopkins in the 1940s,[1] is tetralogy of Fallot. In the normal heart, there are four separate chambers; the two top chambers, or atria, pump blood simultaneously into the two bottom chambers, or ventricles. Blood first enters the heart at the right atrium, which then empties blood into the right ventricle, which pumps the blood into the lungs through the pulmonary artery to get oxygen. From the lungs, the blood enters the left atrium through the pulmonary vein; the left atrium empties into the left ventricle, which pumps the blood into the aorta and from there reaches the rest of the body. Because the left ventricle is responsible for getting blood to the entire body through the aorta, it is usually the biggest and strongest chamber of the heart.

After the body uses up the oxygen delivered by the blood flowing through the arteries, then arterioles, then capillaries, the unoxygenated blood returns to the heart by the capillaries, then venules, then veins.

The blue baby syndrome known as tetralogy of Fallot consists of an incomplete wall between the ventricles (known as a ventricular septal defect or VSD); an aorta that sits over this defect so that its blood comes from both ventricles instead of just from the left (overriding aorta); a defective right ventricular outflow tract near the pulmonary valve that prevents full flow of blood to the lungs; and a muscular right ventricle necessary to accomplish the extra work required to overcome that defect (right ventricular hypertrophy).

Unoxygenated blood from the right ventricle flows into the aorta preferentially because of the obstructed outflow tract into the lungs. This means less blood has the opportunity to be oxygenated in the lungs. Blood mixes abnormally between the left and right ventricles and into the aorta. Oxygen gives blood its reddish color; cyanosis describes the "blueness" in the baby which results from the pumping of mixed oxygenated and unoxygenated blood throughout the body.

Nitrates in drinking water

A sort of "blue baby syndrome" can also be caused by methemoglobinemia.[2][3] It is widely believed to be caused by nitrate contamination in groundwater resulting in decreased oxygen carrying capacity of haemoglobin in babies leading to death. The groundwater can be contaminated by leaching of nitrate generated from fertilizers used in agricultural lands, waste dumps or pit latrines.[4] Cases of blue baby syndrome have been reported in villages in Romania and Bulgaria, and were thought to be caused by groundwater that had been polluted with nitrate leaching from pit latrines.[5] However, the linkages between nitrates in drinking water and blue baby syndrome have been disputed in other studies.[6][7] The syndrome outbreaks might be due to other factors than elevated nitrate concentrations in drinking water.[8]

Other causes

Other insults in neonates, such as respiratory distress syndrome, can also produce a "blue baby syndrome". Like methemoglobinemia, these are not structural lesions and are not regarded by most doctors as true "cyanotic lesions."

Diagnosis

‘Blue Baby’ syndrome has two main symptoms which are easy to pick up if you know what you are looking for. The most obvious is a blue tint to the skin especially around the fingertips, toes and lips. A lack of oxygenated blood cells means there is not enough oxygen to supply the needs of these areas. The other, more stressful symptom is breathlessness. The baby may gasp and wheeze, while slipping in and out of consciousness. It may be weary, have laboured breathing and convulsions may occur. The baby will likely be fatigued and unalert to its surroundings.

Treatment

Surgery

On November 29, 1944, the first successful operation for tetralogy of Fallot was performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. In 1943, the syndrome had been brought to the attention of surgeon Alfred Blalock by pediatric cardiologist Helen B. Taussig. Taussig was trying to figure out a way to treat the hundreds of babies and children who had congenital blue baby syndrome. Blalock's surgical technician, Vivien Thomas, had earlier developed for another purpose a procedure involving the anastomosis, or joining, of the subclavian artery to the pulmonary artery. Adapting this procedure for patients with tetralogy of Fallot gave the blood another chance to become oxygenated. The surgery, which became known as a Blalock-Taussig shunt, rapidly spread worldwide as the treatment of choice for Tetralogy of Fallot.[9] Thomas, an African American, was later recognized as the true developer of the procedure, which is sometimes called the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt. In 1976, Johns Hopkins University presented Thomas with an honorary doctorate.[10]

Epidemiology

Blue baby syndrome or methemoglobinemia mostly affects infants under 6 months of age, although the most common age range is 0 to 4 months. Infants in this age range are vulnerable because they have not matured enough to produce methemoglobin reductase, an oxygen-carrying molecule.[11][12] The most at-risk populations are those with private water sources. Private wells are not regulated by the US government and therefore, if unmonitored, can have higher levels of nitrates, being hazardous to the infants.[13][14] The link between blue baby syndrome in infants and high nitrate levels is well established for waters exceeding the normal limit of 10 mg/L.[15][16] However, there is also evidence that breastfeeding is protective in exposed populations.[17] Many laboratories will provide a water test free of charge.

References

- ↑ "The Blue Baby Operation" (PDF). Blue Baby Operation Exhibit. Johns Hopkins University. June 26, 2000. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Blue baby links - 11 February 2006 - New Scientist". Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ "Blue Baby Syndrome". Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ "The Blue Baby Syndrome".

- ↑ Buitenkamp, M., Richert Stintzing, A. (2008). Europe's sanitation problem - 20 million Europeans need access to safe and affordable sanitation. Women in Europe for a Common Future (WECF), The Netherlands

- ↑ Fewtrell, Lorna (22 July 2004). "Drinking-Water Nitrate, Methemoglobinemia, and Global Burden of Disease: A Discussion". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (14): 1371–1374. PMC 1247562

. PMID 15471727. doi:10.1289/ehp.7216.

. PMID 15471727. doi:10.1289/ehp.7216. - ↑ van Grinsven, Hans JM; Ward, Mary H = 2006 (2006). "Does the evidence about health risks associated with nitrate ingestion warrant an increase of the nitrate standard for drinking water?". Environ Health. 5 (1): 26. PMC 1586190

. PMID 16989661. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-5-26.

. PMID 16989661. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-5-26. - ↑ Ward, Mary H.; deKok, Theo M.; Levallois, Patrick; Brender, Jean; Gulis, Gabriel; Nolan, Bernard T.; VanDerslice, James (23 June 2005). "Workgroup Report: Drinking-Water Nitrate and Health—Recent Findings and Research Needs". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (11): 1607–1614. PMC 1310926

. PMID 16263519. doi:10.1289/ehp.8043.

. PMID 16263519. doi:10.1289/ehp.8043. - ↑ "Hopkins pioneered 'blue baby' surgery 50 years ago 'I Remember ... Thinking It Was Impossible'". Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ "Vivien T. Thomas, L.L.D.". Medical archives. Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ Richard, Alyce M.; Diaz, James H.; Kaye, Alan David (1 January 2014). "Reexamining the Risks of Drinking-Water Nitrates on Public Health". The Ochsner Journal. pp. 392–398. PMC 4171798

. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

. Retrieved 13 June 2017. - ↑ "Nitrates and drinking water". www.bfhd.wa.gov. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ Manassaram, Deana M.; Backer, Lorraine C.; Moll, Deborah M. (1 March 2007). "A review of nitrates in drinking water: maternal exposure and adverse reproductive and developmental outcomes". Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. pp. 153–163. doi:10.1590/S1413-81232007000100018. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ Fan, Anna M; Steinberg, Valerie E (May 27, 1995). "Health implications of nitrate and nitrite in drinking water: An update on methemoglobinemia occurrence and reproductive and developmental toxicity". REGULATORY TOXICOLOGY AND PHARMACOLOGY: 35–43.

- ↑ "Nitrate and Nitrite in Drinking-Water" (PDF). www.who.int. WHO Press. 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ EPA,OW, US. "Table of Regulated Drinking Water Contaminants". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ↑ Pollock, J (1994). "Long term associations with infant feeding in a clinically advantaged population of babies". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 36 – via PubMed.