Blue Angels

| Blue Angels U.S. Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron | |

|---|---|

The Blue Angels F/A-18 Hornets fly in a tight diamond formation, maintaining 18-inch wing tip to canopy separation. | |

| Active | 24 April 1946 – present |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Role | Aerobatic flight demonstration team |

| Size | 16 officers, 110 enlisted |

| Garrison/HQ |

NAS Pensacola NAF El Centro (Winter Airfield) |

| Colors |

"Blue Angel" blue "Insignia" yellow |

| Website |

blueangels |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Cmdr. Ryan Bernacchi |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |

|

| Aircraft flown | |

| Fighter |

3 – McDonnell Douglas F/A-18A Hornets (single seat) 1 – McDonnell Douglas F/A-18B Hornets (two seat) 10 – McDonnell Douglas F/A-18C Hornets (single seat) 2 – McDonnell Douglas F/A-18D Hornets (two seat) *Note – Only 7 F/A-18C/D Hornets are used during a demo. |

| Transport | 1 – C-130T Hercules |

The Blue Angels is the United States Navy's flight demonstration squadron, with aviators from the Navy and Marines. The Blue Angels team was formed in 1946,[1] making it the second oldest formal flying aerobatic team (under the same name) in the world, after the French Patrouille de France formed in 1931.

The Blue Angels' six demonstration pilots currently fly the McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet, typically in more than 70 shows at 34 locations throughout the United States each year, where they still employ many of the same practices and techniques used in their aerial displays in their inaugural 1946 season. An estimated 11 million spectators view the squadron during air shows each full year. The Blue Angels also visit more than 50,000 people in a standard show season (March through November) in schools and hospitals.[2] Since 1946, the Blue Angels have flown for more than 260 million spectators.[3]

Missions

The mission of the United States Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron is "to showcase the pride and professionalism of the United States Navy and Marine Corps by inspiring a culture of excellence and service to country through flight demonstrations and community outreach."[2]

Air show

The Blue Angels' show season runs each year from March until November. They perform at both military and civilian airfields, and often perform directly over major cities such as San Francisco's "Fleet Week" maritime festival, Cleveland's annual Labor Day Air Show, the Chicago Air and Water Show, Jacksonville's Sea and Sky Spectacular, Milwaukee Air and Water Show, and Seattle's annual Seafair festival.

During their aerobatic demonstration, the Blues fly six F/A-18 Hornet aircraft, split into the Diamond Formation (Blue Angels 1 through 4) and the Lead and Opposing Solos (Blue Angels 5 and 6). Most of the show alternates between maneuvers performed by the Diamond Formation and those performed by the Solos. The Diamond, in tight formation and usually at lower speeds (400 mph), performs maneuvers such as formation loops, rolls, and transitions from one formation to another. The Solos showcase the high performance capabilities of their individual aircraft through the execution of high-speed passes, slow passes, fast rolls, slow rolls, and very tight turns. The highest speed flown during an air show is 700 mph (just under Mach 1) and the lowest speed is 120 mph.[2] Some of the maneuvers include both solo aircraft performing at once, such as opposing passes (toward each other in what appears to be a collision course) and mirror formations (back-to-back. belly-to-belly, or wingtip-to-wingtip, with one jet flying inverted). The Solos join the Diamond Formation near the end of the show for a number of maneuvers in the Delta Formation.

The parameters of each show must be tailored in accordance with local weather conditions at showtime: in clear weather the high show is performed; in overcast conditions a low show is performed, and in limited visibility (weather permitting) the flat show is presented. The high show requires at least an 8,000-foot (2,400 m) ceiling and visibility of at least 3 nautical miles (6 km) from the show's centerpoint. The minimum ceilings allowed for low and flat shows are 3,500 feet (~1 km) and 1,500 feet (460 m), respectively.[4]

Origin of squadron name, insignia and paint scheme

When initially formed, the unit was called the Navy Flight Exhibition Team. The squadron was officially redesignated as the United States Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron in December 1974.[5] The original team was christened the Blue Angels in 1946, when one of the pilots came across the name of New York City's Blue Angel Nightclub in The New Yorker magazine; the team introduced themselves as the "Blue Angels" to the public for the first time on 21 July 1946, in Omaha, Nebraska.

The official Blue Angels insignia was designed by then team leader Lt. Cmdr. R. E. "Dusty" Rhodes and Virginia Porter (Illustrator for Naval Air Advanced Training Command), then approved by Chief of Naval Operations in 1949. It is nearly identical to the current design. In the cloud in the upper right quadrant, the aircraft were originally shown heading down and to the right. Over the years, the plane silhouettes have changed along with the squadron's aircraft. Additionally, the lower left quadrant, which contains the Chief of Naval Air Training insignia, has occasionally contained only Naval Aviator wings.

Originally, demonstration aircraft were navy blue (nearly black) with gold lettering. The current shades of blue and yellow were adopted when the team transitioned to the Bearcat in 1946. For a single year, in 1949, the team performed in an all-yellow scheme with blue markings.[6]

Current aircraft

The Blues' McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornets are former fleet aircraft that are nearly combat-ready. Modifications to each aircraft include removal of the aircraft gun and replacement with the tank that contains smoke-oil used in demonstrations, and outfitting with the control stick spring system for more precise aircraft control input. The standard demonstration configuration has a spring tensioned with 40 pounds (18 kg) of force installed on the control stick as to allow the pilot minimal room for uncommanded movement. The Blues do not wear G-suits, because the air bladders inside them would repeatedly deflate and inflate, interfering with the control stick between the pilot's legs. Instead, Blue Angel pilots tense their muscles to prevent blood from rushing from their heads and rendering them unconscious.[7]

In July 2016, Boeing was awarded a $12 million contract to begin an engineering proposal for converting the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet for Blue Angels use, with the proposal to be completed by September 2017.[8]

The show's narrator flies Blue Angel 7, a two-seat F/A-18D Hornet, to show sites. The Blues use this jet for backup, and to give demonstration rides to VIP civilians. Three backseats at each show are available; one of them goes to members of the press, the other two to "Key Influencers".[9] The No. 4 slot pilot often flies the No. 7 aircraft in Friday's "practice" shows.

The Blue Angels use a United States Marine Corps Lockheed C-130T Hercules, nicknamed "Fat Albert", for their logistics, carrying spare parts, equipment, and to carry support personnel between shows. Beginning in 1975, "Bert" was used for Jet Assisted Take Off (JATO) and short aerial demonstrations just prior to the main event at selected venues, but the JATO demonstration ended in 2009 due to dwindling supplies of rockets.[10] "Fat Albert Airlines" flies with an all-Marine crew of three officers and five enlisted personnel. Following the death of Blue Angel 6 pilot Captain Jeff "Koosh" Kuss, USMC, Fat Albert had the honor of flying his remains back to NAS Pensacola, escorted by Kuss' wingman in Blue Angel 5, before then carrying him home to Colorado for burial with full military honors.[11][12][13]

Team members

All team members, both officer and enlisted, pilots and staff officers, come from the ranks of regular Navy and United States Marine Corps units. The demonstration pilots and narrator are made up of Navy and USMC Naval Aviators. Pilots serve two to three years,[2] and position assignments are made according to team needs, pilot experience levels, and career considerations for members.

The officer selection process requires pilots and support officers (flight surgeon, events coordinator, maintenance officer, supply officer, and public affairs officer) wishing to become Blue Angels to apply formally via their chain-of-command, with a personal statement, letters of recommendation, and flight records. Navy and Marine Corps F/A-18 demonstration pilots and naval flight officers are required to have a minimum of 1,250 tactical jet hours and be carrier-qualified. Marine Corps C-130 demonstration pilots are required to have 1,200 flight hours and be an aircraft commander.[14]

Applicants "rush" the team at one or more airshows, paid out of their own finances, and sit in on team briefs, post-show activities, and social events. Rushes are asked to tell a joke prior to the brief and are graded by the team as part of the rigorous selection process. Team members vote in secret on the next year's members, with no accountability to the higher Navy authority why an applicant was or was not selected. Selections must be unanimous. There have been female and racial minority staff officers as official Blue Angel members. The most recent minority Blue Angel pilot was LCDR Keith Hoskins on the 2000 team.[15] Flight surgeons serve a two-year term. They act as the team recorder during air shows and help oversee emergency response planning with the various air show planners. The first female Blue Angel flight surgeon was LT Tamara Schnurr, who was a member of the 2001 team.[16]

The team leader (#1) is the Commanding Officer and is always a Navy Commander, who may be promoted to Captain mid-tour if approved for Captain by the selection board. Pilots of numbers 2–7 are Navy Lieutenants or Lieutenant Commanders, or Marine Corps Captains or Majors. The number 7 pilot narrates for a year, and then typically flies Opposing and then Lead Solo the following two years, respectively. The number 3 pilot moves to the number 4 (slot) position for his second year. Blue Angel No. 4 serves as the demonstration safety officer, due largely to the perspective he is afforded from the slot position within the formation, as well as his status as a second-year demonstration pilot. There are a number of other officers in the squadron, including a Naval Flight Officer, the USMC C-130 pilots, a Maintenance Officer, an Administrative Officer, and a Flight Surgeon. Enlisted members range from E-4 to E-9 and perform all maintenance, administrative, and support functions. They serve three to four years in the squadron.[2] After serving with the Blues, members return to fleet assignments.

Members of the 2017 U.S. Navy Blue Angels are :

- Flying Blue Angel No. 1, Commander Ryan Bernacchi, USN (Commanding Officer/Flight Leader)

- Flying Blue Angel No. 2, Lieutenant Damon Kroes, USN (Right Wing)

- Flying Blue Angel No. 3, Lieutenant Nate Scott, USN (Left Wing)

- Flying Blue Angel No. 4, Lieutenant Lance Benson, USN (Slot)

- Flying Blue Angel No. 5, Commander Frank Weisser, USN (Lead Solo)

- Flying Blue Angel No. 6 Lieutenant Tyler Davies, USN (Opposing Solo)

- Flying Blue Angel No. 7, Lieutenant Brandon Hempler, USN (Advance Pilot/Narrator)

- Events Coordinator, Blue Angel No. 8, Lieutenant Dave Steppe, USN

- Flying Fat Albert, Major Mark Hamilton, USMC

- Flying Fat Albert, Major Mark Montgomery, USMC

- Flying Fat Albert, Major Kyle Maschner, USMC

- Executive Officer, Commander Matt Kaslik, USN

- Maintenance Officer, Lieutenant Samuel Rose, USN

- Flight Surgeon, Lieutenant Juan Guerra, USN

- Administrative Officer, Lieutenant Junior Grade Timothy Hawkins, USN

- Supply Officer, Lieutenant Bryan Pace, USN

- Public Affairs Officer, Lieutenant Joe Hontz, USN

Commanding officer

Commander Ryan Bernacchi joined the Blue Angels in September 2015. He has accumulated more than 3,000 flight hours and 600 carrier-arrested landings, and is a graduate of the U.S. Navy Fighter Weapons School (TOPGUN), NAS Fallon, Nevada. After graduating, he joined the TOPGUN staff as an instructor pilot and served as the Navy and Marine Corps subject matter expert in GPS guided weapons. Ryan served as a Federal Executive Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. His decorations include the Meritorious Service Medal, one Individual Air Medal with Combat "V" (three Strike Flight), four Navy Commendation Medals, one with Combat "V," and numerous unit, campaign, and service awards.

Training and weekly routine

Annual winter training takes place at NAF El Centro, California, where new and returning pilots hone skills learned in the fleet. During winter training, the pilots fly two practice sessions per day, six days a week, in order to fly the 120 training missions needed to perform the demonstration safely. Separation between the formation of aircraft and their maneuver altitude is gradually reduced over the course of about two months in January and February. The team then returns to their home base in Pensacola, Florida, in March, and continues to practice throughout the show season. A typical week during the season has practices at NAS Pensacola on Tuesday and Wednesday mornings. The team then flies to its show venue for the upcoming weekend on Thursday, conducting "circle and arrival" orientation maneuvers upon arrival. The team flies a "practice" airshow at the show site on Friday. This show is attended by invited guests but is often open to the general public. The main airshows are conducted on Saturdays and Sundays, with the team returning home to NAS Pensacola on Sunday evenings after the show. Monday is the Blues' day off.

History

1940s

On 24 April 1946 Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Chester Nimitz issued a directive ordering the formation of a flight exhibition team to boost Navy morale, demonstrate naval air power, and maintain public interest in naval aviation. However, an underlying mission was to help the Navy generate public and political support for a larger allocation of the shrinking defense budget. In April of that year, Rear Admiral Ralph Davison personally selected Lieutenant Commander Roy Marlin "Butch" Voris, a World War II fighter ace, to assemble and train a flight demonstration team, naming him Officer-in-Charge and Flight Leader. Voris selected three fellow instructors to join him (Lt. Maurice "Wick" Wickendoll, Lt. Mel Cassidy, and Lt. Cmdr. Lloyd Barnard, veterans of the War in the Pacific), and they spent countless hours developing the show. The group perfected its initial maneuvers in secret over the Florida Everglades so that, in Voris' words, "if anything happened, just the alligators would know". The team's first demonstration before Navy officials took place on 10 May 1946 and was met with enthusiastic approval.

On 15 June Voris led a trio of Grumman F6F-5 Hellcats, specially modified to reduce weight and painted sea blue with gold leaf trim, through their inaugural 15-minute-long performance at their Florida home base, Naval Air Station Jacksonville.[1] The team employed a North American SNJ Texan, painted and configured to simulate a Japanese Zero, to simulate aerial combat. This aircraft was later painted yellow and dubbed the "Beetle Bomb". This aircraft is said to have been inspired by one of the Spike Jones' Murdering the Classics series of musical satires, set to the tune (in part) of the William Tell Overture as a thoroughbred horse race scene, with "Beetle Bomb" being the "trailing horse" in the lyrics.

The team thrilled spectators with low-flying maneuvers performed in tight formations, and (according to Voris) by "keeping something in front of the crowds at all times. My objective was to beat the Army Air Corps. If we did that, we'd get all the other side issues. I felt that if we weren't the best, it would be my naval career." The Blue Angels' first public demonstration also netted the team its first trophy, which sits on display at the team's current home at NAS Pensacola.

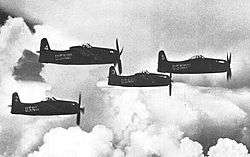

On 25 August 1946 the squadron upgraded their aircraft to the Grumman F8F-1 Bearcat. In May 1947, flight leader Lt. Cmdr. Bob Clarke replaced Butch Voris as the leader of the team and introduced the famous Diamond Formation, now considered the Blue Angels' trademark.

In 1949, the team acquired a Douglas R4D Skytrain for logistics to and from show sites. The team's SNJ was also replaced by a F8F-1 "Bearcat", painted yellow for the air combat routine, inheriting the "Beetle Bomb" nickname. The Blues transitioned to the straight-wing Grumman Grumman F9F-2 Panther on 13 July 1949, wherein the F8F-1 "Beetle Bomb" was relegated to solo aerobatics before the main show, until it crashed on takeoff at a training show in Pensacola in 1950.

Team headquarters shifted from NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, to NAAS Whiting Field, Florida, in the fall of 1949, announced 14 July 1949.[17]

1950s

The "Blues" continued to perform nationwide until the start of the Korean War in 1950, when (due to a shortage of pilots, and no planes were available) the team was disbanded and its members were ordered to combat duty. Once aboard the aircraft carrier USS Princeton the group formed the core of VF-191, Satan's Kittens.

The Blue Angels were officially recommissioned on 25 October 1951, and reported to NAS Corpus Christi, Texas. Lt. Cdr. Voris was again tasked with assembling the team (he was the first of only two commanding officers to lead them twice). In 1953 the team traded its Sky Train for a Curtiss R5C Commando.

In August 1953, "Blues" leader LCDR Ray Hawkins became the first naval aviator to survive an ejection at supersonic speeds when his F9F-6 became uncontrollable on a cross-country flight.[18][19][20]

The first Marine Corps pilot, Capt Chuck Hiett, joined the team and they relocated to their current home of NAS Pensacola in the winter of 1954.[21] It was here they progressed to the swept-wing Grumman F9F-8 Cougar.

In September 1956, the team added a sixth aircraft to the flight demonstration in the Opposing Solo position, and gave its first performance outside the United States at the International Air Exposition in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It also upgraded its logistics aircraft to the Douglas R5D Skymaster.

In January 1957, the team left its winter training facility at Naval Air Facility El Centro, California for a ten-year period. For the next ten years, the team would winter at NAS Key West, Florida. For the 1957 show season, the Blue Angels transitioned to the supersonic Grumman F11F-1 Tiger, first flying the short-nosed, and then the long-nosed versions. The first Six-Plane Delta Maneuvers were added in the 1958 season.

1960s

In July 1964, the Blue Angels participated in the Aeronaves de Mexico Anniversary Air Show over Mexico City, Mexico, before an estimated crowd of 1.5 million people.

In 1965, the Blue Angels conducted a Caribbean island tour, flying at five sites. Later that year, they embarked on a European tour to a dozen sites, including the Paris Air Show, where they were the only team to receive a standing ovation.

The Blues toured Europe again in 1967 touring six sites. In 1968 the C-54 Skymaster transport aircraft was replaced with a Lockheed VC-121J Constellation. The Blues transitioned to the two-seat McDonnell Douglas F-4J Phantom II in 1969, nearly always keeping the back seat empty for flight demonstrations. The Phantom was the only plane to be flown by both the "Blues" and the United States Air Force Thunderbirds. That year they also upgraded to the Lockheed C-121 Super Constellation for logistics.

1970s

The Blues received their first U.S. Marine Corps Lockheed KC-130F Hercules in 1970. An all-Marine crew manned it. That year, they went on their first South American tour. In 1971, the team conducted its first Far East Tour, performing at a dozen locations in Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Guam, and the Philippines. In 1972, the Blue Angels were awarded the Navy's Meritorious Unit Commendation for the two-year period from 1 March 1970 – 31 December 1971. Another European tour followed in 1973, including air shows in Tehran, Iran, England, France, Spain, Turkey, Greece, and Italy.

In December 1974 the Navy Flight Demonstration Team downsized to the subsonic Douglas A-4F Skyhawk II and was reorganized into the Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron. This reorganization permitted the establishment of a commanding officer (the flight leader), added support officers, and further redefined the squadron's mission emphasizing the support of recruiting efforts. Commander Tony Less was the squadron's first official commanding officer.

1980s

On 8 November 1986 the Blue Angels completed their 40th anniversary year during ceremonies unveiling their present aircraft, the McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet, the first multi-role fighter/attack aircraft. The power and aerodynamics of the Hornet allows them to perform a slow, high angle of attack "tail sitting" maneuver, and to fly a "dirty" (landing gear down) formation loop, the last of which is not duplicated by the USAF Thunderbirds.

Also in 1986, LCDR Donnie Cochran, joined the Blue Angels as the first African-American Naval Aviator to be selected. He would return to lead the team in 1993.

The Blue Angels Creed, written by JO1 Cathy Konn, 1991–1993

1990s

In 1992 the Blue Angels deployed for a month-long European tour, their first in 19 years, conducting shows in Sweden, Finland, Russia (first foreign flight demonstration team to perform there), Romania, Bulgaria, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Spain.

In 1998, CDR Patrick Driscoll made the first "Blue Jet" landing on a "haze gray and underway" aircraft carrier, USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75).

2000s

In 2006, the Blue Angels marked their 60th year of performing.[22] On 30 October 2008 a spokesman for the team announced that the team would complete its last three performances of the year with five jets instead of six. The change was because one pilot and another officer in the organization had been removed from duty for engaging in an "inappropriate relationship". The Navy stated that one of the individuals was a man and the other a woman, one a Marine and the other from the Navy, and that Rear Admiral Mark Guadagnini, chief of Naval air training, was reviewing the situation.[23] At the next performance at Lackland Air Force Base following the announcement the No. 4 or slot pilot, was absent from the formation. A spokesman for the team would not confirm the identity of the pilot removed from the team.[24] On 6 November 2008 both officers were found guilty at an admiral's mast on unspecified charges but the resulting punishment was not disclosed.[25] The names of the two members involved were later released on the Pensacola News Journal website/forum as pilot No. 4 USMC Maj. Clint Harris and the administrative officer, Navy Lt. Gretchen Doane.[26]

The Fat Albert performed its final JATO demonstration at the 2009 Pensacola Homecoming show, expending their 8 remaining JATO bottles. This demonstration not only was the last JATO performance of the squadron, but also the final JATO use of the U.S. Marine Corps.[27]

In 2009, the Blue Angels were inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.[28]

2010s

On 22 May 2011, the Blue Angels were performing at the Lynchburg Regional Airshow in Lynchburg, Virginia, when the Diamond formation flew the Barrel Roll Break maneuver at an altitude that was lower than the required minimum altitude.[29] The maneuver was aborted, the remainder of the demonstration canceled and all aircraft landed safely. The next day, the Blue Angels announced that they were initiating a safety stand-down, canceling their upcoming Naval Academy Airshow and returning to their home base in Pensacola, Florida, for additional training and airshow practice.[30] On 26 May, the Blue Angels announced they would not be flying their traditional fly-over of the Naval Academy Graduation Ceremony and that they were canceling their 28–29 May 2011 performances at the Millville Wings and Wheels Airshow in Millville, New Jersey.

On 27 May 2011, the Blue Angels announced that Commander Dave Koss, the squadron's Commanding Officer, would be stepping down. He was replaced by Captain Greg McWherter, the team's previous Commanding Officer.[31] The squadron canceled performances at the Rockford, Illinois Airfest 4–5 June and the Evansville, Indiana Freedom Festival Air Show 11–12 June to allow additional practice and demonstration training under McWherter's leadership.[31]

Between 2 and 4 September 2011 on Labor Day weekend, the Blue Angels flew for the first time with a 50–50 blend of conventional JP-5 jet fuel and a camelina-based biofuel at Naval Air Station Patuxent River airshow at Patuxent River, Maryland.[32][33] McWherter flew an F/A-18 test flight on 17 August and stated there were no noticeable differences in performance from inside the cockpit.[34][35]

On 1 March 2013, the U.S. Navy announced that it was cancelling remaining 2013 performances after 1 April 2013 due to sequestration budget constraints.[36][37][38] In October 2013, Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, stating that "community and public outreach is a crucial Departmental activity", announced that the Blue Angels (along with the U.S. Air Force's Thunderbirds) would resume appearing at air shows starting in 2014, although the number of flyovers will continue to be severely reduced.[39]

In June 2014, Captain Greg McWherter, flight leader of the Blue Angels for 2008-2010 and 2011-2012, received letter of reprimand from Adm. Harry Harris after an admiral's mast for “failing to stop obvious and repeated instances of sexual harassment, condoning widespread lewd practices within the squadron and engaging in inappropriate and unprofessional discussions with his junior officers" during his second tour with the team.[40]

In July 2014, Marine Corps Capt. Katie Higgins, 27, became the first female pilot to join the Blue Angels.[41][42]

Aircraft timeline

The "Blues" have flown eight different demonstration aircraft and five support aircraft models:[43]

- Demonstration aircraft

- Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat: June–August 1946

- Grumman F8F-1 Bearcat: August 1946 – 1949

- Grumman F9F-2 Panther: 1949 – June 1950 (first jet); F9F-5 Panther: 1951 - Winter 1954/55

- Grumman F9F-8 Cougar: Winter 1954/55 - mid-season 1957 (swept-wing)

- Grumman F11F-1 (F-11) Tiger: mid-season 1957 – 1968 (first supersonic jet)

- McDonnell Douglas F-4J Phantom II: 1969 – December 1974

- Douglas A-4F Skyhawk: December 1974 – November 1986

- McDonnell Douglas F/A-18A/B/C/D Hornet (F/A-18B/D are #7 aircraft): November 1986 – present

- Support aircraft

- Douglas R4D Skytrain: 1949–1955

- Curtiss R5C Commando: 1953

- Douglas R5D Skymaster: 1956–1968

- Lockheed C-121 Super Constellation: 1969–1973

- Lockheed C-130 Hercules "Fat Albert": 1970–present

- Miscellaneous aircraft

- North American SNJ Texan "Beetle Bomb" (used to simulate a Japanese A6M Zero aircraft in demonstrations during the late 1940s)

- Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star (Used during the 1950s as a VIP transport aircraft for the team)

- Vought F7U Cutlass (two of the unusual F7Us were received in late 1952 and flown as a side demonstration during the 1953 season but they were not a part of their regular formations which at the time used the F9F Panther. Pilots and ground crew found it unsatisfactory and plans to use it as the team's primary aircraft were cancelled).

Show routine

The following is the show routine used on 17 May 2008:[44]

- Fat Albert (C-130) – high-performance takeoff (Low Transition)

- Fat Albert – Parade Pass (Photo Pass. The plane banks around the front of the crowd)

- Fat Albert – Flat Pass

- Fat Albert – Head on Pass

- Fat Albert – Short-Field Assault Landing

- FA-18 Engine Start-Up and Taxi Out

- Diamond Take-off (Either a low transition with turn, loop on takeoff, a half-Cuban 8 takeoff, or a Half Squirrel Cage)

- Solos Take-off (Blue Angel #5: Dirty Roll on Take-Off; Blue Angel #6: Low Transition to High Performance Climb)

- Diamond 360: Aircraft 1, 2, 3 and 4 are in their signature 18" wingtip-to-canopy diamond formation.

- Opposing Knife-Edge Pass

- Diamond Roll: The whole diamond formation rolls as a single entity.

- Opposing Inverted to Inverted Rolls

- Diamond Aileron Roll: All 4 diamond jets perform simultaneous aileron rolls.

- Fortus: Solos flying in carrier landing configuration with No.5 inverted, establishing a "mirror image" effect.

- Diamond Dirty Loop: The diamond flies a loop with all 4 jets in the carrier landing configuration.

- Minimum Radius Turn (Highest G maneuver. No.5 flies a "horizontal loop" pulling 7 Gs to maintain a tight radius)

- Double Farvel: Diamond formation flat pass with aircraft 1 and 4 inverted.

- Opposing Minimum Radius Turn

- Echelon Parade

- Opposing Horizontal Rolls

- Left Echelon Roll: The roll is made into the Echelon, which is somewhat difficult for the outside aircraft.

- Sneak Pass: the fastest speed of the show is about 700 mph (just under Mach 1 at sea level) Video

- Line-Abreast Loop – the most difficult formation maneuver to do well. No.5 joins the diamond as the 5 jets fly a loop in a straight line

- Opposing Four-Point Hesitation Roll

- Vertical Break

- Opposing Vertical Pitch

- Barrel Roll Break

- Section High-Alpha Pass: (tail sitting), the show's slowest maneuver[45] Video

- Low Break Cross

- Inverted Tuck Over Roll

- Tuck Under Break

- Delta Roll

- Fleur de Lis

- Solos Pass to Rejoin, Diamond flies a loop

- Loop Break Cross (Delta Break): After the break the aircraft separate in six different directions, perform half Cuban Eights then cross in the center of the performance area.

- Delta Breakout

- Delta Pitch Up Carrier Break to Land

Accidents

During its history, 27 Blue Angels pilots have been killed in air show or training accidents.[46] Through the 2006 season there have been 262 pilots in the squadron's history,[47] giving the job a 10% fatality rate.

- 29 September 1946 – Lt. Ross "Robby" Robinson was killed during a performance when a wingtip broke off his Bearcat, sending him into an unrecoverable spin.

- 1952 – Two Panthers collided during a demonstration in Corpus Christi, Texas and one pilot was killed. The team resumed performances two weeks later.

- 2 August 1958 - Lt. John R. Dewenter landed, wheels up at Buffalo Niagara International Airport after experiencing engine troubles during a show in Clarence, NY. The Grumman F-11 Tiger landed on Runway 23 but exited airport property coming to rest in the intersection of Genesee Street and Dick Road, nearly hitting a gas station. Lt. Dewenter was uninjured, but the plane was a total loss.

- 14 October 1958 – Cmdr. Robert Nicholls Glasgow died during an orientation flight just days after reporting for duty as the new Blue Angels leader.[48]

- 15 March 1964 – Lt. George L. Neale, 29, was killed during an attempted emergency landing at Apalach Airport near Apalachicola, Florida. Lt. Neale's F-11A Tiger had experienced mechanical difficulties during a flight from West Palm Beach, Florida to NAS Pensacola, causing him to attempt the emergency landing. Failing to reach the airport, he ejected from the aircraft on final approach, but his parachute did not have sufficient time to fully deploy.[49]

- 2 September 1966 – Lt. Cmdr. Dick Oliver crashed his Tiger and was killed at the Canadian International Air Show in Toronto.

- 1 February 1967 – Lt Frank Gallagher was killed when his Tiger stalled during a practice Half Cuban 8 maneuver and spun into the ground.

- 18 February 1967 – Capt. Ronald Thompson was killed when his Tiger struck the ground during a practice formation loop.

- 14 January 1968 – Opposing solo Lt. Bill Worley was killed when his Tiger crashed during a practice double immelman.

- 30 August 1970 – Lt. Ernie Christensen belly-landed his F-4J Phantom at the Eastern Iowa Airport in Cedar Rapids when he inadvertently left the landing gear in the up position.[50] He ejected safely, while the aircraft slid off the runway.

- 4 June 1971 – CDR Harley Hall safely ejected after his Phantom caught fire and crashed during practice over Narragansett Bay near the ex-NAS Quonset Point in Rhode Island.

- 14 February 1972 – Lt. Larry Watters was killed when his F-4J Phantom II struck the ground, upright, while practicing inverted flight, during winter training at NAF El Centro.

- 8 March 1973 – Capt. John Fogg, Lt. Marlin Wiita and LCDR Don Bentley survived a multi-aircraft mid-air collision during practice over the Superstition Mountains in California.

- 26 July 1973 – 2 pilots and a crew chief were killed in a mid-air collision between 2 Phantoms over Lakehurst, NJ during an arrival practice. Team Leader LCDR Skip Umstead, Capt. Mike Murphy and ADJ1 Ron Thomas perished. The rest of the season was cancelled after this incident.

- 22 February 1977 – Opposing solo Lt. Nile Kraft was killed when his Skyhawk struck the ground during practice.

- 8 November 1978 – One of the solo Skyhawks struck the ground after low roll during arrival maneuvers at NAS Miramar. Navy Lieutenant Michael Curtin was killed.

- April 1980 – Lead Solo Lt. Jim Ross was unhurt when his Skyhawk suffered a fuel line fire during a show at NS Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico. LT Ross stayed with and landed the plane which left the end of the runway and taxied into the woods after a total hydraulic failure upon landing.

- 22 February 1982 – Lt. Cmdr Stu Powrie, Lead Solo was killed when his Skyhawk struck the ground during winter training at Naval Air Facility El Centro, California just after a dirty loop.

- 13 July 1985 – Lead and Opposing Solo Skyhawks collided during a show at Niagara Falls, killing opposing solo Lt. Cmdr. Mike Gershon. Lt. Andy Caputi ejected and parachuted to safety.[51]

- 12 February 1987 – Lead solo Lt. Dave Anderson ejected from his Hornet after a dual engine flameout during practice near El Centro, CA.

- 23 January 1990 – Two Blue Angel Hornets suffered a mid-air collision during a practice at El Centro. Marine Corps Maj. Charles Moseley ejected safely. Cmdr. Pat Moneymaker was able to land his airplane, which then required a complete right wing replacement.[52]

- 28 October 1999 – Lt. Cmdr. Kieron O'Connor, flying in the front seat of a two-seat Hornet, and recently selected demonstration pilot Lt. Kevin Colling (in the back seat) struck the ground during circle and arrival maneuvers in Valdosta, Georgia. Neither pilot survived.[53]

- 1 December 2004 – Lt. Ted Steelman ejected from his F/A-18 approximately one mile off Perdido Key after his aircraft struck the water, suffering catastrophic engine and structural damage. He suffered minor injuries.[54]

- 21 April 2007 – Lt. Cmdr. Kevin J. Davis crashed his Hornet near the end of the Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort airshow in Beaufort, South Carolina, and was killed.[55]

- 2 June 2016 – Capt. Jeff "Kooch" Kuss, (Opposing Solo, Blue Angel No. 6), died just after takeoff while performing the Split-S maneuver in his F/A-18 Hornet during a practice run for The Great Tennessee Air Show in Smyrna, Tennessee. The Navy investigation found that Capt. Kuss performed the maneuver at too low of an altitude while failing to retard the throttle out of afterburner, causing him to fall too fast and recover at too low of an altitude. Capt. Kuss ejected, but his parachute was immediately engulfed in flames, causing him to fall to his death. Kuss' body was recovered multiple yards away from the crash site. The cause of death was blunt force trauma to the head. The investigation also cites weather and pilot fatigue as additional causes to the crash.[56] In a strange twist, Captain Kuss' fatal crash happened hours after the Blue Angels' fellow pilots in the United States Air Force Thunderbirds suffered a crash of their own following the United States Air Force Academy graduation ceremony earlier that day.[57]

Other incidents involving former Blue Angels

- 8 March 1951 – LCDR Johnny Magda,[58] while flying in Korea, was the first former Blue Angel killed in combat.

- 27 January 1973 – CDR Harley Hall (1970 team leader) was shot down flying an F-4J over Vietnam, and was officially listed as missing in action.

In the media

- The Blue Angels was a dramatic television series, starring Dennis Cross and Don Gordon, inspired by the team's exploits and filmed with the cooperation of the Navy. It aired in syndication from 26 September 1960 to 3 July 1961.[59]

- The Blue Angels were the subject of "Flying Blue Angels", a pop song recorded by George, Johnny and the Pilots (Coed Co 555), that debuted on Billboard Magazine's "Bubbling Under the Hot 100" chart on 11 September 1961.

- Threshold: The Blue Angels Experience is a 1975 documentary film, written by Dune author Frank Herbert, featuring the team in practice and performance during their F-4J Phantom era; many of the aerial photography techniques pioneered in Threshold were later used in the film Top Gun.[60]

- In 2005, the Discovery Channel aired a documentary miniseries, Blue Angels: A Year in the Life, focusing on the intricate day-to-day details of that year's training and performance schedule.[61][62]

- The video for the American rock band Van Halen's 1986 release "Dreams" consists of Blue Angels performance footage. The video was originally shot featuring the Blues in the A-4 Skyhawk. A later video features the F/A-18 Hornet.

- The Blue Angels appeared in the episodes "Death Begins at Forty" and "Insult to Injury" of Tim Allen's television sitcom Home Improvement as themselves.

- The Blue Angels made a brief appearance on I Love Toy Trains part 3.

- The Blue Angels were featured in the IMAX film Magic of Flight.

- In 2009, the MythBusters enlisted the aid of Blue Angels to help test the myth that a sonic boom could shatter glass.[63]

- The Blue Angels are a major part of the novel Shadows of Power by James W. Huston.[64]

- Blue Angels and the Thunderbirds is a 4 disc SkyTrax DVD set © 2012 TOPICS Entertainment, Inc. It features highlights from airshows performed in the U.S.A. shot from inside and outside the cockpit including interviews of squadron aviators, plus aerial combat footage taken during Desert Storm, histories of the two flying squadrons from 1947 through 2008 including on-screen notes on changes in Congressional budgeting and research program funding, photo gallery slide shows, and two "forward-looking" sequences Into the 21st Century detailing developments of the F/A-18 Hornet's C and E and F models (10 min.) and footage of the F-22 with commentary (20 min.).

- In the television micro-series Star Wars: Clone Wars, Anakin Skywalker's starfighter is named Azure Angel, after the Blue Angels team.[65]

- In My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic, the Wonderbolts are based on the Blue Angels.[66]

Notable alumni

- Chuck Brady – Astronaut

- Donnie Cochran – first African-American Blue Angels aviator and commander

- Edward L. Feightner – World War II fighter ace and Lead Solo

- Anthony A. Less - First Commanding Officer of Blue Angels squadron, numerous other commands including Naval Air Forces Atlantic Fleet

- Robert L. Rasmussen – Aviation Artist

- Raleigh Rhodes —World War II veteran and third leader of the Blue Angels[67]

- Roy Marlin Voris – First Blue Angel leader

- Patrick M. Walsh – Left Wingman and Slot Pilot, 1985–1987; Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Former Vice Chief of Naval Operations and White House Fellow

Budget

In November 2011, the Blue Angels received $37 million annually, out of the annual DoD budget.[68][69]

See also

- List of United States Navy aircraft squadrons

- United States Air Force Thunderbirds

- United States Marine Corps Aviation

References

- 1 2 "History of the Blue Angels". Blue Angels official site.

- ↑ "United States Navy: The Blue Angels History". Navy.mil. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "What determines high show vs. low show for Blue Angels? | KING5.com Seattle". King5.com. 6 August 2010. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Campbell, War Paint, p. 171.

- ↑ "Blue Angels Frequently Asked Questions". Blueangels.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "Contracts for July 25, 2016". U.S. Department of Defense. 25 July 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "Flights with the Blue Angels". Flyfighterjet.com. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ McCullough, Amy (9 November 2009). "Abort Launch: Air shows to do without Fat Albert’s famed JATO". Marine Corps Times. Gannett Company. p. 6.

- ↑ "Thousands Honor Fallen Blue Angel As Remains Come Home". June 7, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Remains of fallen Blue Angels pilot arrive in Colorado for funeral". Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Capt. Jeff Kuss’ remains come home to Durango". The Durango Herald. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Gosport article, March 02, 2012, "Blue Angels Seek Officer Applicants", page 2" (PDF). Gosport NAS Pensacola Base Newspaper.

- ↑ "Blue Angels Alumni 2000". blueangels-usn.org.

- ↑ "Blue Angels Alumni 2001". blueangels-usn.org.

- ↑ Fort Walton, Florida, "'Blue Angels' To Pensacola – Navy Flight Exhibition Team Is Transferred", Playground News, Thursday 14 July 1949, Volume 4, Number 24, page 2.

- ↑ "2005". ejection-history.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-11-16.

- ↑ Wilcox, R.K. (2004). First Blue: The Story of World War II Ace Butch Voris and the Creation of the Blue Angels. St. Martin's Press. pp. 2–237. ISBN 9780312322496. Retrieved 2014-11-16.

- ↑ "BLUE ANGEL EJECTS AT HIGH SPEED", Naval Aviation News October, 1952, republished at http://www.blueangels.org/NANews/Articles/Oct53/Oct53.htm

- ↑ Gall, Sandy. "How well do you know the Blue Angels?". CHIPS: the Department of the Navy's Information Technology Magazine. Department of the Navy. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ "Blue Angels Monumental Moments". Navy.com. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Moon, Troy (31 October 2008). "Blues Angels Pilot, Other Grounded". Pensacola News Journal. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ↑ Griggs, Travis (2 November 2008). "No. 4 jet missing from Blue Angels". Pensacola News Journal. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ↑ Scutro, Andrew, "2 Blue Angels found guilty, await punishment", Military Times, 8 November 2008.

- ↑ "A (Potentially) Disgraced Angel (updated)", Defensetech.org

- ↑ "End of JATO for Blue Angels!", blueangels.navy.mil, November 2009

- ↑ International Air & Space Hall of Fame San Diego Air & Space Museum

- ↑ horsemoney (25 May 2011). "Blue Angels Lynchburg Va. 2011 was this the problem formation?" – via YouTube.

- ↑ Blue Angels Cancel Naval Academy Airshow Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. blueangels.navy.mil.

- 1 2 "Blue Angels commander steps down after subpar performance". CNN. 27 May 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ↑ "Blue Angels Use Biofuel At Patuxent Air Show | Aero-News Network". Aero-news.net. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ John Pike (9 January 2011). "Blue Angels to Soar on Biofuel During Labor Day Weekend Air Show". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Austell, Jason (1 September 2011). "Blue Angels Go Green". NBC San Diego. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "Blue Angels Use Biofuel at Patuxent Air Show". Military.com. 7 September 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Military spending cuts ground Blue Angels, Thunderbirds 1 March 2013 NBC News

- ↑ U.S. Navy Cancels Blue Angels 2013 Performances 10 April 2013, U.S. Navy

- ↑ "Thunderbirds, Blue Angels to Resume Air Shows". ABC News.

- ↑ "Former Blue Angels CO reprimanded for 'toxic' climate". Navy Times. June 3, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ↑ Pope, Stephen (July 24, 2014). "First Female Pilot Joins Blue Angels". Flying. Retrieved May 9, 2015 – via flyingmag.com.

- ↑ Prudente, Tim (May 6, 2015). "Breaking a gender barrier at 370 mph: Severna Park pilot becomes first woman to fly with elite Blue Angels". Baltim. Sun. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "Joint Services Open House (Andrews AFB) 2008". AirshowStuff.com. 17 May 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ↑ Blue Angels FAQ Archived 4 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Investigators probe Blue Angels crash, MSNBC, 22 April 2007

- ↑ Blue Angels Alumni FAQ, last updated 17 March 2007.

- ↑ Blue Angels crash artifacts found 50 years later, Associated Press, 3 March 2009 Archived 10 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Basham, Dusty, "Blue Angel Pilot Killed – Jet Fighter Falls Near Apalachicola", Playground Daily News, Fort Walton Beach, Florida, Monday Morning, 16 March 1964, Volume 18, Number 27, pages 1, 2.

- ↑ https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=v91VAAAAIBAJ&sjid=A9gDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6426,63638&dq=threshold+the+blue+angels+experience&hl=en

- ↑ ""Navy Blue Angel Aviators Die in Crash", 28 October 1999, accessed 23 April 2007". Usmilitary.about.com. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Clausen, Christopher (13 June 1990). "Pilot Blamed In Blue Angel Crash". Pensacola News Journal. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ ""Blue Angel crash victims identified", CNN, 28 October 1999, accessed 23 April 2007". CNN. 28 October 1999. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ ""Blue Angels Pilot Ejects Before Plane Crashes", ''Fox News'', 2 December 2004, accessed 23 April 2007". Fox News. 1 December 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Navy "Blue Angels" jet crashes. Reuters

- ↑ "Botched Maneuver Caused Blue Angels Pilot's Death: Investigation". Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Blue Angels pilot killed in Tennessee crash". Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ↑ Johnny Magda findagrave.com

- ↑ "The Blue Angels". 26 September 1960 – via IMDb.

- ↑ "Threshold: The Blue Angels Experience". 1 September 1975 – via IMDb.

- ↑ Blue Angels: A Year in the Life Archived 11 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ ""Blue Angels: A Year in the Life" (2005)". Imdb.com. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "Mythbusters Episode Features Blue Angels, June 10th - Aero-News Network".

- ↑ "Shadows of Power". jameswhuston.com. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ "Star Wars: Blogs - Keeper of the Holocron's Blog - The Blue Angels/Star Wars connection". 1 March 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009.

- ↑ "Jayson Thiessen (@goldenrusset)". Twitter.com. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Combat pilot in two wars led Blue Angels". Los Angeles Times. 7 December 2007. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ↑ "Blue Angels fly into age of budget woes". USA Today. 23 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ↑ "Blue Angels FAQ". Archived from the original on 4 April 2012.

Further reading

- (2012). "My incredible flight aboard the Blue Angels" By Charles Atkeison

- (2005). "The First Blue Angel." Miramar 50th Air Show Special Commemorative Program 18.

- (2005). "The Blue Angels History." Miramar 50th Air Show Special Commemorative Program 22.

- Blue Angels Timeline (1946–1980) accessed 10 November 2005.

- "Grumman and the Blue Angels" article by William C. Barto at the Grumman Memorial Park official website – accessed 15 October 2005.

- "First Blue: The story of World War II Ace Butch Voris and the Creation of the Blue Angels" by Robert K. Wilcox, Thomas Dunne Books/St.Martins Press, 2004, robertkwilcox.com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blue Angels. |