Blood cell

A blood cell, also called a haematopoietic cell, hemocyte, or hematocyte, is a cell produced through hematopoiesis and found mainly in the blood.

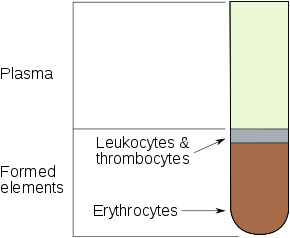

- Red blood cells – Erythrocytes

- White blood cells – Leukocytes

- Platelets – Thrombocytes.

Together, these three kinds of blood cells add up to a total 45% of the blood tissue by volume, with the remaining 55% of the volume composed of plasma, the liquid component of blood.[1] The volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood (hematocrit) is measured by centrifuge or flow cytometry and is 45% of cells to total volume in males and 40% in females.[2]

Haemoglobin (the main component of red blood cells) is an iron-containing protein that facilitates transportation of oxygen from the lungs to tissues and carbon dioxide from tissues to the lungs.

Pulmonary Circulation- is the flow of blood from your heart to your lungs and back to the heart

Red blood cells

Red blood cells or erythrocytes, primarily carry oxygen and collect carbon dioxide through the use of haemoglobin, and have a lifetime of about 120 days. In the process of being formed they go through a unipotent stem cell stage. They have the job alongside the white blood cells of protecting the healthy cells.

RBCs are formed in the red bone marrow in the adults. After the completion of their lifespan, they are destroyed in the spleen.

White blood cells

White blood cells or leukocytes, are cells of the immune system involved in defending the body against both infectious disease and foreign materials. Five diverse types of leukocytes exist, and are all produced and derived from multipotent cells in the bone marrow known as a hematopoietic stem cells. They live for about 3 to 4 days in the average human body. Leukocytes are found throughout the body, including the blood and lymphatic system.

The two main categories of white blood cells are granulocytes and agranulocytes.

Neutrophils (a type of granulocyte) are the most abundant of all the WBCs.

Platelets

Platelets, or thrombocytes or yellow blood cells, are very small, irregularly shaped clear cell fragments (i.e. cells that do not have a nucleus containing DNA), 2–3 µm in diameter, which derive from fragmentation of precursor megakaryocytes. The average lifespan of a platelet is normally just 5 to 9 days. Platelets are a natural source of growth factors. They circulate in the blood of mammals and are involved in hemostasis, leading to the formation of blood clots. Platelets release thread-like fibers to form these clots.

If the number of platelets is too low, excessive bleeding can occur. However, if the number of platelets is too high, blood clots can form thrombosis, which may obstruct blood vessels and result in such events as a stroke, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism—or blockage of blood vessels to other parts of the body, such as the extremities of the arms or legs. An abnormality or disease of the platelets is called a thrombocytopathy, which can be either a low number of platelets (thrombocytopenia), a decrease in function of platelets (thrombasthenia), or an increase in the number of platelets (thrombocytosis). There are disorders that reduce the number of platelets, such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), that typically cause thromboses, or clots, instead of bleeding.

Platelets release a multitude of growth factors including Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), a potent chemotactic agent, and TGF beta, which stimulates the deposition of extracellular matrix. Both of these growth factors have been shown to play a significant role in the repair and regeneration of connective tissues. Other healing-associated growth factors produced by platelets include basic fibroblast growth factor, insulin-like growth factor 1, platelet-derived epidermal growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor. Local application of these factors in increased concentrations through Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been used as an adjunct to wound healing for several decades.

Complete blood count

A complete blood count (CBC) is a test panel requested by a doctor or other medical professional that gives information about the cells in a patient's blood. A scientist or lab technician performs the requested testing and provides the requesting medical professional with the results of the CBC. In the past, counting the cells in a patient's blood was performed manually, by viewing a slide prepared with a sample of the patient's blood under a microscope. Today, this process is generally automated by use of an automated analyzer, with only approximately 10-20% of samples now being examined manually. Abnormally high or low counts may indicate the presence of many forms of disease, and hence blood counts are amongst the most commonly performed blood tests in medicine, as they can provide an overview of a patient's general health status.

Discovery

In 1658 Dutch naturalist Jan Swammerdam was the first person to observe red blood cells under a microscope, and in 1695, microscopist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, also Dutch, was the first to draw an illustration of "red corpuscles", as they were called. No further blood cells were discovered until 1842 when French physician Alfred Donné discovered platelets. The following year leukocytes were first observed by Gabriel Andral, a French professor of medicine, and William Addison, a British physician, simultaneously. Both men believed that both red and white cells were altered in disease. With these discoveries, hematology, a new field of medicine, was established. Even though agents for staining tissues and cells were available, almost no advances were made in knowledge about the morphology of blood cells until 1879, when Paul Ehrlich published his technique for staining blood films and his method for differential blood cell counting [3]

References

- ↑ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ↑ Purves, William K.; Sadava, David; Orians, Gordon H.; Heller, H. Craig (2004). Life: The Science of Biology (7th ed.). Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. p. 954. ISBN 0-7167-9856-5.

- ↑ http://www.annclinlabsci.org/content/33/2/237.full.pdf