Long Island City

| Long Island City | |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood of Queens | |

|

Long Island City in 2015 | |

| Nickname(s): "LIC" | |

Long Island City  Long Island City  Long Island City | |

| Coordinates: Coordinates: 40°45′03″N 73°56′28″W / 40.7509°N 73.9411°W | |

| Country | United States |

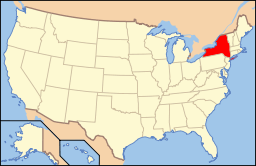

| State | New York |

| City | New York City |

| County/Borough | Queens |

| Population | |

| • Total | 68,117 |

| ZIP code | 11101–11106, 11109, 11120 |

| Area code(s) | 718, 347, 917 |

Long Island City (L.I.C.) is the westernmost residential and commercial neighborhood of the New York City borough of Queens. L.I.C. is noted for its rapid and ongoing residential growth and gentrification, its waterfront parks, and its thriving arts community.[1] L.I.C. has among the highest concentration of art galleries, art institutions, and studio space of any neighborhood in New York City.[2] It is bordered by Astoria to the north; the East River to the west; Hazen Street, 49th Street, and New Calvary Cemetery in Sunnyside to the east; and Newtown Creek—which separates Queens from Greenpoint, Brooklyn—to the south. It originally was the seat of government of the Town of Newtown, and remains the largest neighborhood in Queens. The area is part of Queens Community Board 1, located north of the Queensboro Bridge and Queens Plaza; it is also of Queens Community Board 2 to the south.

Long Island City is the eastern terminus of the Queensboro Bridge, also known as the 59th Street Bridge, which is the only non-toll automotive route connecting Queens and Manhattan. Northwest of the bridge terminus are the Queensbridge Houses, a development of the New York City Housing Authority and the largest public housing complex in North America.

History

Long Island City, as its name suggests, was formerly a city, created in 1870 from the merger of the Village of Astoria and the hamlets of Ravenswood, Hunters Point, Blissville, Sunnyside, Dutch Kills, Steinway, Bowery Bay and Middleton in the Town of Newtown.[3] At time of incorporation, Long Island City had between 12,000 and 15,000 residents.[3] Its charter provided for an elected mayor and a ten-member Board of Alderman with two representing each of the city's five wards.[3] City ordinances could be passed by a majority vote of the Board of Aldermen and the mayor's signature.[4]

Long Island City held its first election on July 5, 1870.[5] Residents elected A.D. Delmars the first mayor; Delmars ran as both a Democrat and a Republican.[5] The first elected Board of Aldermen was H. Rudolph and Patrick Lonirgan (Ward 1); Francis McNena and William E. Bragaw (Ward 2); George Hunter and Mr. Williams (Third Ward); James R. Bennett and John Wegart (Ward Four); and E.M. Hartshort and William Carlin (Fifth Ward).[5] The mayor and the aldermen were inaugurated on July 18, 1870.[6]

In the 1880s, Mayor De Bevoise nearly bankrupted the Long Island City government by embezzling, of which he was convicted.[7] Many dissatisfied residents of Astoria circulated a petition to ask the New York State Legislature to allow it to secede from Long Island City and reincorporate as the Village of Astoria, as it existed prior to the incorporation of Long Island City, in 1884.[7] The petition was ultimately dropped by the citizens.[8]

Long Island City continued to exist as an incorporated city until 1898, when all of Queens was annexed to New York City.[9] The last mayor of Long Island City was a notorious Irish-American named Patrick Jerome "Battle-Axe" Gleason.

The city surrendered its independence in 1898 to become part of the City of Greater New York. However, Long Island City survives as ZIP code 11101 and ZIP code prefix 111 (with its own main post office) and was formerly a sectional center facility (SCF). Since 1985, the Greater Astoria Historical Society, a nonprofit cultural and historical organization, has been preserving the past and promoting the future of the neighborhoods that are part of historic Long Island City.

The Common Council of Long Island City in 1873 adopted the coat of arms as "emblematical of the varied interest represented by Long Island City." It was designed by George H. Williams, of Ravenswood. The overall composition was inspired by New York City's coat of arms. The shield is rich in historic allusion, including Native American, Dutch, and English symbols.[10] In 1898, Long Island City became part of New York City.

Through the 1930s, numerous subway tunnels, the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, and the Queensboro Bridge were built to connect the neighborhood to Manhattan. By the 1970s, the factories in Long Island City were being abandoned. In 1981, Queens West on the west side of Long Island City was developed to revitalize the area. Finally, in 2001, the neighborhood was rezoned from an industrial neighborhood to a residential neighborhood, and the area underwent gentrification, with developments such as Hunter's Point South being built in the area.[11]

In 2006, a resident of nearby Woodside, Hiroyuki Takenaga, proposed establishing a Japantown in Long Island City.[12]

In addition to the Hunters Point Historic District and Queensboro Bridge, the 45th Road – Court House Square Station (Dual System IRT), Long Island City Courthouse Complex, and United States Post Office are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[13]

Commerce and economy

Developments and buildings

Long Island City was once home to many factories and bakeries, some of which are finding new uses. The former Silvercup bakery is now home to Silvercup Studios, which has produced notable works such as NBC's 30 Rock and HBO's Sex and the City. The Silvercup sign is visible from the IRT Flushing Line and BMT Astoria Line trains going into and out of Queensboro Plaza (7 <7> N W trains). The former Sunshine Bakery is now one of the buildings which houses LaGuardia Community College. Other buildings on the campus originally served as the location of the Ford Instrument Company, which was at one time a major producer of precision machines and devices. Artist Isamu Noguchi converted a photo-engraving plant into a workshop; the site is now the Noguchi Museum, a space dedicated to his work.

The Standard Motor Products headquarters, a manufacturing site producing items like distributor caps, was once located in the industrial neighborhood of Long Island City until purchased by Acuman Partners in 2008 for $40M. The Standard Motor Products Building was put on the market by Acuman in 2014 and acquired by RXR Realty, LLC for $110M. The former factory built in 1919 now houses the Jim Henson Company, Society Awards, and a commercial rooftop farm run by Brooklyn Grange.[14]

High-rise housing is being built on a former Pepsi-Cola site on the East River. From June 2002 to September 2004, the former Swingline Staplers plant was the temporary headquarters of the Museum of Modern Art. Other former factories in Long Island City include Fisher Electronics and Chiclets Gum. Long Island City's turn-of-the-century district of residential towers, called Queens West, is located along the East River, just north of the LIRR's Long Island City Station. Redevelopment in Queens West reflects the intent to have the area as a major residential area in New York City, with its high-rise residences very close to public transportation, making it convenient for commuters to travel to Manhattan by ferry or subway. The first tower, the 42-floor Citylights, opened in 1998 with an elementary school at the base. Others have been completed since then and more are being planned or under construction.

Today, the most prominent structure, other than Queensboro Bridge, is the community's green skyscraper, the 658-foot (201 m) Citicorp Building built in 1989 on Courthouse Square. It is the tallest building on Long Island and in any of the New York City boroughs outside Manhattan.[15] Socioeconomic diversity is very visible in Long Island City; the Queensbridge Houses are composed of over 3,000 units, making it the largest public housing complex in North America.

Companies

Eagle Electric, now known as Cooper Wiring Devices, was one of the last major factories in the area, before it moved to China; Plant #7, which was the largest of their factories and housed their corporate offices, is being converted to residential luxury lofts.[16][17]

Long Island City is currently home to the largest fortune cookie factory in the United States, owned by Wonton Foods and producing four million fortune cookies a day. Lucky numbers included on fortunes in the company's cookies led to 110 people across the United States winning $100,000 each in a May 2005 drawing for Powerball.[18][19][20]

Online grocery company FreshDirect serves the greater New York metropolitan area via deliveries from a warehouse and administrative offices on Borden Avenue. A customer can also order online and come to the warehouse for pickup.

The Brooks Brothers tie manufacturing factory, which employs 122 people and produces more than 1.5 million ties per year, has operated in Long Island City since 1999.[21]

Long Island City is the new home of independent film studio Troma.

On March 22, 2010, JetBlue Airways announced it was moving its headquarters from Forest Hills to Long Island City, also incorporating the jobs from its Darien, Connecticut, office. The airline, which operates its largest hub at JFK Airport, also operates from LaGuardia Airport, and made the Brewster Building in Queens Plaza its home.[22][23] The airline moved there around mid-2012.[24]

Subsections

In 1870, the villages of Astoria, Ravenswood, Hunters Point, Dutch Kills, Middletown, Sunnyside, Blissville, and Bowery Bay were incorporated into Long Island City.[25]

Dutch Kills

Dutch Kills was a hamlet, named for its navigable tributary of Newtown Creek, that occupied what today is centrally Queensboro Plaza. Dutch Kills was an important road hub during the American Revolutionary War, and the site of a British Army garrison from 1776 to 1783. The area supported farms during the 19th century. The canalization of Newtown Creek and the Kills at the end of the 19th century intensified industrial development of the area, which prospered until the middle of the 20th century. The neighborhood is currently undergoing a massive rezoning of mixed residential and commercial properties.[25][26]

Blissville

Blissville, which has the ZIP code 11101, is a neighborhood within Long Island City, located at 40°44'4.87"N73°56'9.81"W[27] and bordered by Calvary Cemetery to the east; the Long Island Expressway to the north; Newtown Creek to the south; and Dutch Kills, a tributary of Newtown Creek, to the west. Blissville was named after Neziah Bliss, who owned most of the land in the 1830s and 1840s.[28] Bliss built the first version of what was known for many years as the Blissville Bridge, a drawbridge over Newtown Creek, connecting Greenpoint, Brooklyn and Blissville; it was replaced in the 20th century by the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge, also called the J. J. Byrne Memorial Bridge, located slightly upstream. Blissville existed as a small village until 1870 when it was incorporated into Long Island City.[25] Historically an industrial neighborhood, it has a small park with a monument at 54th Avenue and 48th Street.

Hunters Point

|

Hunters Point Historic District | |

Religious procession crossing 50th Avenue, 1989. Church at rear is undergoing repair. | |

| |

| Location | Along 45th Ave., between 21st and 23rd Sts., New York, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°44′40.14″N 73°57′12.71″W / 40.7444833°N 73.9535306°W |

| Area | 1.5 acres (0.61 ha) |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Mixed (more Than 2 Styles From Different Periods) |

| NRHP Reference # | [13] |

| Added to NRHP | September 19, 1973 |

Hunters Point is on the south side of Long Island City.[29][30][31][32] It contains the Hunters Point Historic District, a national historic district that includes 19 contributing buildings along 45th Avenue between 21st and 23rd Streets. They are a set of townhouses built in the late 19th century.[33] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[13]

Queens West and Hunter's Point South are located on the waterfront.

Arts and culture

Long Island City is home to a large and dynamic artistic community.

- Long Island City was the home of 5 Pointz, a building housing artists' studios, which was legally painted on by a number of graffiti artists and was prominently visible near the Court Square station on the 7 <7> trains.[34] The 5 Pointz building was painted over and demolished, starting in 2013.[35]

- The Fisher Landau Center for Art is a private foundation that offers regular exhibitions of contemporary art.

- Across the street from Socrates Sculpture Park is the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Museum, founded in 1985 by Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi. After undergoing a two and a half year renovation, the museum opened in 2004 with newer and advanced facilities.

- MoMA PS1, an affiliate of the Museum of Modern Art, is the oldest and second-largest non-profit arts center in the United States solely devoted to contemporary art. It is named after the former public school in which it is housed.

- SculptureCenter is New York City's only non-profit exhibition space dedicated to contemporary and innovative sculpture. SculptureCenter re-located from Manhattan's Upper East Side to a former trolley repair shop in Long Island City, Queens renovated by artist/designer Maya Lin in 2002. Founded by artists in 1928, SculptureCenter has undergone much evolution and growth, and continues to expand and challenge the definition of sculpture. SculptureCenter commissions new work and presents exhibits by emerging and established, national and international artists. The museum also hosts a diverse range of public programs including lectures, dialogues, and performances.

- Socrates Sculpture Park is an outdoor sculpture park located one block from the Noguchi Museum at the intersection of Broadway and Vernon Boulevard.

- The Queens Library maintains two branches in Long Island City, one on the ground floor of the Citicorp Building (the Court Square branch), and one on 21st Street.

- See.me is web-based arts organization located in Long Island City. The organization is dedicated to supporting artistic talent, harnessing online creative communities, and promoting artists' work.

Recreation

- City Ice Pavilion, with 33,000 square feet (3,100 m2) of skating surface, opened in Long Island City in late 2008. The skating rink is on the roof of a two-story storage facility.[36]

- Water Taxi Beach was New York City's first non-swimming urban beach, and was located on the East River in Long Island City. City Hall planned to build 5,000 moderate income apartments in this area, a 30-acre (120,000 m2) development called Hunter's Point South.[37] The beach later closed and the apartments have been constructed.

Demographics

As of the 2010 U.S. Census, Long Island City comprises a population that is 1% Native American Indian, 10% African American, 15% Asian or Pacific Islander, 52% White, 9% mixed race, and 15% of "other" demographics. There is an equal proportion of female residents to male residents.[38][39]

Transportation

Long Island City is served by the elevated BMT Astoria Line at two stations (N W trains) and IRT Flushing Line at four stations (7 <7> trains) of the New York City Subway. It is also served by the underground IND 63rd Street Line at one station (F train), the IND Queens Boulevard Line at two stations (E M R trains), and IND Crosstown Line at two stations (G train).[40] The Long Island City and Hunterspoint Avenue stations of the Long Island Rail Road are also located within Long Island City.

During the summer, the New York Water Taxi Company used to operate Water Taxi Beach, a public beach artificially created on a wharf along the East River, accessible at the corner of Second Street and Borden Avenue.[41] It was discontinued in 2011 due to new construction on the site of the old landing.[42]

Cars enter by the Pulaski Bridge, the Queensboro Bridge, the Queens–Midtown Tunnel, and the Roosevelt Island Bridge connecting Long Island City and Astoria to Roosevelt Island. Major thoroughfares include 21st Street, which is mostly industrial and commercial; I-495 (Long Island Expressway); the westernmost portion of Northern Boulevard, which becomes Jackson Avenue (the former name of Northern Boulevard) south of Queens Plaza; and Queens Boulevard, which leads westward to the bridge and eastward follows New York State Route 25 through Long Island; and Vernon Boulevard.

In June 2011, NY Waterway started service to points along the East River.[43] On May 1, 2017, that route became part of the NYC Ferry's East River route, which runs between Pier 11/Wall Street in Manhattan's Financial District and the East 34th Street Ferry Landing in Murray Hill, Manhattan, with five intermediate stops in Brooklyn and Queens. [44][45] One NYC Ferry stop for the East River route is located at Hunters Point South,[46] while another NYC Ferry stop for a route to Astoria is located at Gantry Plaza State Park.[47]

Education

The New York City Department of Education operates a facility in Long Island City housing the Office of School Support Services and several related departments.[48]

K-12

Long Island City is served by the New York City Department of Education. Long Island City is zoned to:

- P.S. 17 Henry David Thoreau School

- P.S. 70

- P.S. 76 William Hallet School

- P.S. 78

- P.S. 85 Judge Charles Vallone

- P.S. 111 Jacob Blackwell School

- P.S. 112 Dutch Kills School

- P.S. 150

- P.S. 166 Henry Gradstein School

- P.S. 171 Peter G. Van Alst School

- P.S. 199 Maurice A. Fitzgerald School

- I.S. 10 H. Greeley School

- I.S. 141 The Steinway School

- I.S. 204 Oliver W. Holmes

- I.S. 126 Albert Shanker School For Visual And Performing Arts

Additionally, Long Island City is home to:

- Baccalaureate School for Global Education, a 7-12 school

- Queens Paideia School, an independent progressive school that offers personalized learning and group activities for its mixed-age student body, K-8

High schools offering specializations

Long Island City is home to numerous high schools, a number of which offer specializations, as indicated below. These specialized schools are not to be confused with SHSAT-based high schools. Rather, these schools offer programs that are included at SHSAT schools.

- Academy of American Studies (Q575), a history high school

- Academy for Careers in Television & Film (Q301)

- Academy of Finance and Enterprise (Q264)

- Aviation Career and Technical High School (Q610)

- Bard High School Early College II (Q299)

- Frank Sinatra School of the Arts (Q501)

- High School of Applied Communication (Q267)

- Information Technology High School (Q502)

- The International High School (Queens) at LaGuardia Community College (Q530)

- Long Island City High School (Q450)

- Middle College High School at LaGuardia Community College (Q520)

- Newcomers High School - Academy for New Americans (Q555)

- Queens Vocational and Technical High School (Q600)

- Robert F. Wagner Jr. Institute For Arts & Technology (Q560)

- William Cullen Bryant High School (Q445)

Higher education

Numerous institutions of higher education have (or have had) a presence in Long Island City.

- Briarcliffe College has a campus on Thomson Avenue.

- City University of New York School of Law is located at 2 Court Square.

- Columbia University's Depression Project is located at 3718 34th Street.

- DeVry University - New York Metro (also known as DeVry College of New York), maintained headquarters at 3020 Thomson Avenue until March 2011, at which time New York Metro's main campus relocated to 180 Madison Avenue in Manhattan, and DCNY relocated its Queens presence to 99-21 Queens Boulevard in Rego Park[49]

- LaGuardia Community College is located at 3110 Thomson Avenue.

- Middle College National Consortium is located at 27-28 Thomson Avenue, #331

- Touro College is located at 2511 49th Avenue.

Mayors

Long Island City was incorporated and had elected mayors from 1870 to 1898, when it and the rest of Queens were annexed to New York City.

| Name | Tenure | Party |

|---|---|---|

| A.D. Ditmars[5] | 1870–1873 | Democrat, Republican[lower-alpha 1] |

| Henry S. De Bevoise[50][lower-alpha 2] | 1873–1874 | Democrat |

| George H. Hunter (acting)[51][52][lower-alpha 2] | 1873–1874 | Democrat |

| Henry S. De Bbevoise[51][52][lower-alpha 2] | 1874–1875 | Democrat |

| A.D. Ditmars[53][lower-alpha 3] | 1875 | Democrat |

| John Quinn (acting)[54] | 1875–1876 | Democrat |

| Henry S. De Bevoise[55][56] | 1876–1883 | Democrat |

| George Petry[57] | 1883–1887 | Independent Democrat, Republican[58] |

| Patrick J. Gleason[59] | 1887–1897 | Democrat[60] |

- ↑ Delmars' candidacy was endorsed by the Democratic and Republican parties.[5] In 1873, Delmars unsuccessfully ran for reelection as an Independent Democrat.

- 1 2 3 Mayor Debevoise was temporarily removed from office following accusations of embezzlement in September 1873.[51] George H. Hunter served as acting mayor until the Board of Aldermen withdrew the articles of impeachment in April 1874.[51][52]

- ↑ Mayor Ditmars resigned due to financial embarrassments, ill health, and intention to move south.[54]

Notable residents

Seven Major League Baseball players were born in Long Island City:

- Joe Benes (1901)

- Ed Boland (1908)

- Al Cuccinello (1914)

- Tony Cuccinello (1907)

- Billy Loes (1929)

- Gus Sandberg (1895)

- Billy Zitzmann (1895)

Two Major League Baseball players have died in Long Island City:

- John Hatfield (1909)

- Dike Varney (1950)

The NBA's Metta World Peace and filmmaker Julie Dash[61] both grew up in the Queensbridge Houses, as did hip-hop producer Marley Marl, and rappers MC Shan, Mobb Deep, Nas, and Roxanne Shante.

Other famous residents of Long Island City include:

- Sonam Dolma Brauen, Swiss-Tibetan sculptor and painter[62]

- Richard Christy, musician and writer on The Howard Stern Show

- Roy Gussow, abstract sculptor[63]

- Steve Hofstetter, actor and comedian; operates the Laughing Devil Comedy Club in the area.

- Zenon Konopka, ice hockey forward; lived in Long Island City during the 2010–11 NHL season

- Natalia Paruz, musician and director of the annual NYC Musical Saw Festival

References

Notes

- ↑ Silver, Nate (April 11, 2010). "The Most Livable Neighborhoods in New York". New York. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ↑ Roleke, John. "Long Island City Art Tour". About.com. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "The New Long Island City--Provisions of the Proposed Charter". The New York Times. February 20, 1870. p. 6.

- ↑ "Long Island City--Ordinances of the Common Council". The New York Times. August 6, 1870. p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Election in Long Island City". The New York Times. July 6, 1870. p.8.

- ↑ "Inauguration of the Long Island City Officers--Message of the Mayor". The New York Times. July 19, 1870. p. 5.

- 1 2 "Unhappy Long Island City". The New York Times. February 18, 1884. p. 8.

- ↑ "Long Island". The New York Times. March 8, 1884. p. 8.

- ↑ Greater Astoria Historical Society; Jackson, Thomas; Melnick, Richard (2004). Long Island City. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 0-7385-3666-0.

- ↑ "History Topics: LIC Coat of Arms". Greater Astoria Historical Society. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Queens West Villager". Queens West Villager. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ↑ Gill, John Freeman. "For a Big Dreamer, a Little Tokyo." The New York Times. February 5, 2006. Retrieved on September 5, 2013.

- 1 2 3 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Zlomek, Erin. "Redeveloping New York Factories Into Small Business Hubs". www.businessweek.com. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Citicorp Building". Emporis. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.astorialic.org/topics/industry/lirr/volume4/volume4_p.php

- ↑ http://ny.curbed.com/archives/2014/06/20/inside_a_tobeconverted_long_island_city_warehouse.php

- ↑ Lee, Jennifer (May 11, 2005). "Who Needs Giacomo? Bet on the Fortune Cookie". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ↑ Snow, Mary (May 12, 2005). "Cookies Contain Fortunes for Powerball Winners". CNN. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ Olshan, Jeremy (June 6, 2005). "Cookie Master". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ Tschorn, Adam (September 10, 2009). "Behind The Knot: A Quick Tour of Brooks Bros. NYC Tie Factory". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ↑ McGeehan, Patrick (March 22, 2010). "JetBlue to Remain 'New York's Hometown Airline'". The New York Times. Associated Press. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ↑ McGeehan, Patrick (March 22, 2010). "JetBlue to Move West Within Queens, Not South to Orlando". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ↑ "JetBlue Plants Its Flag in New York City with New Headquarters Location" (Press release). JetBlue Airways. March 22, 2010. Archived from the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Greater Astoria Historical Society; Jackson, Thomas; Melnick, Richard (2004). Long Island City. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 0-7385-3666-0.

- ↑ Information about Dutch Kills from the Greater Astoria Historical Society

- ↑ Information about Blissville from the Greater Astoria Historical Society

- ↑ Walsh, Kevin (2006). Forgotten New York: Views of a lost metropolis. New York: HarperCollins.

- ↑ Hunters Point, Queens: Neighborhood Profile at About.com

- ↑ Queensmark Comes To Hunters Point, Queens Historical Society

- ↑ Information about Hunters Point from the Greater Astoria Historical Society

- ↑ Forgotten New York: Hunters Point

- ↑ Stephen S. Lash and Betty J. Ezequelle (January 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Hunters Point Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved January 16, 2011. See also: "Accompanying photo".

- ↑ Bayliss, Sarah (August 8, 2004). "Museum With (Only) Walls". The New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ↑ . "Deal Reached For '5Pointz' Development In Queens". NY1. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ↑ Kaminer, Ariel (December 27, 2009). "Ice, Served Two Ways: Plain or Glamorous". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (November 10, 2008). "Disputed Queens Housing Faces a Vote This Week". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ↑ Population Demographics

- ↑ LIC Partnership – Demographics

- ↑ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. June 25, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ↑ Cline, Francis (August 11, 2005). ""Imagination on The Waterfront" in Queens". NY Times. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Water Taxi Beach Long Island City". watertaxibeach.com. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ↑ Grynbaum, Michael M.; Quinlan, Adriane (June 13, 2011). "East River Ferry Service Begins". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ↑ "NYC launches ferry service with Queens, East River routes". NY Daily News. Associated Press. 2017-05-01. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ↑ Levine, Alexandra S.; Wolfe, Jonathan (2017-05-01). "New York Today: Our City’s New Ferry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ↑ "Routes and Schedules: East River". NYC Ferry.

- ↑ "Routes and Schedules: Astoria". NYC Ferry.

- ↑ Home page. New York City Department of Education Office of School Support Services. Retrieved on May 1, 2013. "2004 The Office of School Support Services 44-36 Vernon Boulevard Long Island City, NY 11101"

- ↑ "DeVry College of New York Campus Community Homepage". Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Long Island City Mayorality". The New York Times. June 15, 1873. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 "City and Suburban News: Long Island". The New York Times. September 25, 1873. p. 8.

- 1 2 3 "Municipal Troubles in Long Island City". The New York Times. April 25, 1874. p. 7.

- ↑ "Long Island City Government". The New York Times. July 14, 1875. p. 5.

- 1 2 "Resignation of a Mayor". The New York Times. November 12, 1875. p. 8.

- ↑ "Too Much Government: The Affairs of Long Island City—A Demand for the Amendment of the Charter". The New York Times. February 4, 1879. p. 8.

- ↑ "Alleged Ballot Box Stuffing". The New York Times. November 4, 1880. p. 8.

- ↑ "Mayor De Bevoise Ousted". The New York Times. January 13, 1883. p. 5.

- ↑ "Queens County Elections: The Majority of Mr. Otis—Gleason's Defeat in Long Island City". The New York Times. November 8, 1883. p. 2.

- ↑ "Long Island". The New York Times. January 2, 1886. p. 2.

- ↑ "The Election in Long Island". The New York Times. November 3, 1886. p. 2

- ↑ Lee, Felicia R. (December 3, 1997). "In the Old Neighborhood With: Julie Dash; Home Is Where the Imagination Took Root". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ↑ Eisenvogel (Across Many Mountains) in: di Giovanni, Janine (March 7, 2011). "Across Many Mountains: Escape from Tibet". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ Hevesi, Dennis (February 20, 2011). "Roy Gussow, Abstract Sculptor, Dies at 92". New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

Further reading

-

"Long Island City". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Long Island City". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. -

"Long Island City". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Long Island City". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Long Island City, Queens. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Queens/Long Island City and Astoria. |

- Queens Buzz Lead-in Section to LIC

- Long Island City BID

- LICNotes

- Greater Astoria Historical Society

- LIC Cultural Alliance