Blazon

| Part of a series on |

| Heraldic achievement |

|---|

| Conventional elements of coats of arms |

|

|

In heraldry and heraldic vexillology, a blazon is a formal description of a coat of arms, flag or similar emblem, from which the reader can reconstruct the appropriate image. The verb to blazon means to create such a description. The visual depiction of a coat of arms or flag traditionally has considerable latitude in design, while a blazon specifies the essentially distinctive elements; thus it can be said that a coat of arms or flag is primarily defined not by a picture but rather by the wording of its blazon (though often flags are in modern usage additionally and more precisely defined using geometrical specifications). Blazon also refers to the specialized language in which a blazon is written, and, as a verb, to the act of writing such a description. This language has its own vocabulary, grammar and syntax, or rules governing word order, which becomes essential for comprehension when blazoning a complex coat of arms.

Other objects — such as badges, banners, and seals — may also be described in blazon.

The word blazon (referring to a verbal description) is not to be confused with the verb to emblazon, or the noun emblazonment, both of which relate to the graphic representation of a coat of arms or heraldic device.

Etymology

The word blazon is derived from French blason, "shield." It was found in English by the end of the 14th century.[1]

Formerly, experts in heraldry assumed that the word was related to the German verb blasen, "to blow (a horn)".[2][3] Present-day lexicographers reject this theory as conjectural and disproved.[1]

Grammar

The blazon of armorials follows a rigid formula, designed to eliminate ambiguity of interpretation, to be as concise as possible and to avoid repetition and extraneous punctuation. English antiquarian Charles Boutell stated:

Heraldic language [emphasis in original] is most concise, and it is always minutely exact, definite, and explicit; all unnecessary words are omitted, and all repetitions are carefully avoided; and, at the same time, every detail is specified with absolute precision. The nomenclature is equally significant, and its aim is to combine definitive exactness with a brevity that is indeed laconic.[4]

The rules of blazonry are as follows:

- Every blazon of a coat of arms begins by describing the field (background), with first letter as a capital, followed by a comma ",". In a majority of cases this is a single tincture; e.g. Azure (blue). If the field is complex, the variation is described, followed by the tinctures used; e.g. Chequy gules and argent (checkered red and white). If the shield is divided, the division is described, followed by the tinctures of the subfields, beginning with the dexter side (shield bearer's right, but viewer's left) of the chief (upper) edge; e.g. Party per pale argent and vert (dexter half silver, sinister half green), or Quarterly argent and gules (clockwise from viewer's top left i.e. dexter chief: white, red, white, red). The most common tincture names are historically abbreviated.

- A Tincture is named only once in a given blazon. If there is a need to reference a tincture multiple times, it is named by arranging all elements of like tincture together prior to the tincture name e.g. ar. (argent) two chevrons and a canton gu (gules); its position in the blazon, "of the first", "of the field", e.g. ar. (argent) two chevrons and on a canton gu a lion passant of the first.

- The principal charge(s) are then named, with their tincture(s); e.g. a bend or.

- The principal charge is followed by any other charges placed around or on it. If a charge be a bird or beast, its attitude is described, followed by the animal's tincture, followed by anything that may be differently coloured; e.g. An eagle displayed gules armed and wings charged with trefoils or (see the coat of arms of Brandenburg).

Any accessories present — such as crown/coronet, helmet, torse, mantling, crest, motto, supporters and compartment — are then described in turn, using the same terminology and syntax.

- According to Boutell (1864): "It appears desirable always to print all heraldic blazon in italic".[5] Heraldry has its own vocabulary, word-order and punctuation, and showing it in italics thus indicates to the reader the presence of a quasi-foreign language.

Party per pale argent and vert, a tree eradicated counterchanged. Arms of Behnsdorf.

Party per pale argent and vert, a tree eradicated counterchanged. Arms of Behnsdorf. Argent, an eagle displayed gules armed and wings charged with trefoils Or. Arms of Brandenburg.

Argent, an eagle displayed gules armed and wings charged with trefoils Or. Arms of Brandenburg.

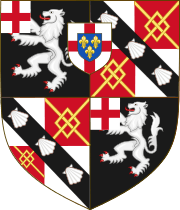

A quartered (composite) shield is blazoned one quarter (panel) at a time, proceeding by rows from chief (top) to base, and within each row from dexter (the right side of the bearer holding the shield) to sinister; in other words, from the viewer's left to right. A divided shield is blazoned "party per [line of division]" or "parted per [line of division]", though the word "party" or "parted" is almost always omitted (e.g. "Per pale argent and vert, a tree eradicated counterchanged"). A tincture is sometimes replaced by "of the first", "of the second" etc. to avoid repetition of tincture names; they refer to the order in which the tinctures were first mentioned. "Counterchanged" means that a charge which straddles a line of division is tinctured of the same tinctures as the divided field, reversed (see Behnsdorf arms pictured above).

But as to the rigid formulae of blazoning, John Brooke-Little, Norroy and Ulster King of Arms, wrote in 1985: “Although there are certain conventions as to how arms shall be blazoned ... many of the supposedly hard and fast rules laid down in heraldic manuals [including those by heralds] are often ignored.”[7]

A given coat-of-arms may be drawn in many different ways, all considered equivalent, just as the letter "A" may be printed in many different fonts while still being the same letter. For example, the shape of the escutcheon is almost always immaterial, so long as it is not of an anachronistic variety, a rare exception being the coat of arms of Nunavut, for which a round shield is specified.

French grammar

Because heraldry developed at a time when English clerks wrote in Anglo-Norman French, many terms in English heraldry are of French origin, as is the practice of placing most adjectives after nouns rather than before. A problem arises as to acceptable spellings of French words used in English blazons, especially in the case of adjectival endings, determined in normal French usage by gender and number. It is considered by some heraldic authorities as pedantry to adopt strictly correct linguistic usage for English blazons:

To describe two hands as appaumées, because the word main is feminine in French, savours somewhat of pedantry. A person may be a good armorist, and a tolerable French scholar, and still be uncertain whether an escallop-shell covered with bezants should be blazoned as bezanté or bezantée. (Cussans, Handbook of Heraldry, 1898)

Cussans (1898) adopted the convention of spelling all French adjectives in the masculine singular, without regard to the gender and number of the nouns they qualify; however, as Cussans admits, the commoner convention is to spell all French adjectives in the feminine singular form, for example: a chief undée and a saltire undée, even though the French nouns chef and sautoir are in fact masculine.[8]

Tinctures

Tincture is the term used to describe the background of a field. It can be a colour, a metal or a fur (i.e. pattern). In a black and white representation of arms (such as in bookplates), colors are represented through the use of hatching or patterns of lines and dots. The list of tinctures and their names are listed below.

- Metals

- Or (or)(gold, shown as yellow), very common

- Argent (ar)(silver, shown as white, never grey), very common

- Colours

- Gules (gu)(red), very common

- Azure (az)(blue), very common

- Sable (sa)(black), very common

- Vert (vert)(green), uncommon.

- Purpure (purp)(purple), rare.

- Tenné (orange), very rare.

- Sanguine (blood red), very rare.

- Murrey (mulberry), very rare.

- Bleu-celeste (sky blue), very rare.

- Furs

- Ermine, common.

- Vair, common,

- Ermines, rare.

- Erminois, rare.

- Erminites, rare.

- Pean, rare.

- Potent, rare.

Complexity

Full descriptions of shields range in complexity, from a single word to a convoluted series describing compound shields:

- Arms of Brittany: Ermine

- Azure, a Bend Or, over which the families of Scrope and Grosvenor fought a famous legal battle (see Scrope v Grosvenor and image above).

- Arms of Östergötland, Sweden: Gules, a Griffin with dragon wings tail and tongue rampant Or armed beaked langued and membered Azure between four Roses Argent.

- Arms of Hungary dating from 1867, when part of Austria-Hungary:

Quarterly I. Azure three Lions' Heads affronté Crowned Or (for Dalmatia); II. chequy Argent and Gules (for Croatia); III. Azure a River in Fess Gules bordered Argent thereon a Marten proper beneath a six-pointed star Or (for Slavonia); IV. per Fess Azure and Or over all a Bar Gules in the Chief a demi-Eagle Sable displayed addextré of the Sun-in-splendour and senestré of a Crescent Argent in the Base seven Towers three and four Gules (for Transylvania); enté en point Gules a double-headed Eagle proper on a Peninsula Vert holding a Vase pouring Water into the Sea Argent beneath a Crown proper with bands Azure (for Fiume); over all an escutcheon Barry of eight Gules and Argent impaling Gules on a Mount Vert a Crown Or issuant therefrom a double-Cross Argent (for Hungary).[9]

Arms of Brittany

Arms of Brittany Arms of Östergötland

Arms of Östergötland.svg.png) Arms of Hungary (1867)

Arms of Hungary (1867)

See also

References

- 1 2 "blazon, n.". OED Online. June 2012. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/20024 (accessed September 10, 2012).

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th. ed., vol.11, p.683, "Heraldry"

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Blazon". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Blazon". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Boutell, Charles, Heraldry, Historical and Popular, 3rd Edition, London, 1864, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Boutell, 1864, p.11

- ↑ Courtenay, P. The Armorial Bearings of Sir Winston Churchill Archived 2013-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.. The Churchill Centre.

- ↑ J P Brooke-Little: An heraldic alphabet (new and revised edition), p. 52. Robson Books, London, 1985.

- ↑ Example from Cussans, Handbook of Heraldry, 1898, p.47

- ↑ Velde, François (August 1998). "Hungary". Heraldry by Countries. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- General

- Brault, Gerard J. (1997). Early Blazon: Heraldic Terminology in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, (2nd ed.). Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-711-4.

- Elvin, Charles Norton. (1969). A Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Heraldry Today. ISBN 0-900455-00-4.

- Parker, James. A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry, (2nd ed.). Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Co. ISBN 0-8048-0715-9.

External links

-

The dictionary definition of blazon at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of blazon at Wiktionary -

Media related to Illustrated atlas of French and English heraldic terms at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Illustrated atlas of French and English heraldic terms at Wikimedia Commons - Heraldric Dictionary

- A Heraldic Primer, by Stephen Gold and Timothy Shead, explaining the terminology in detail

- A Grammar of Blazonry by Bruce Miller

- "Commonly Known" Heraldic Blazon/Emblazon Knowledge, an SCA page with a lengthy dictionary of blazon terms

- Public Register of the Canadian Heraldic Authority with many useful official versions of modern coats of arms, searchable online

- Civic Heraldry of England and Wales, fully searchable with illustrations

- Arms of members of the Heraldry Society of Scotland, fully searchable with illustrations of bearings

- Arms of members of the Heraldry Society (England), with illustrations of bearings

- Members' Roll of Arms of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada, with illustrations of bearings