Black drink

Black drink is a name for several kinds of ritual beverages brewed by Native Americans in the Southeastern United States. Traditional ceremonial people of the Yuchi,[1] Caddo,[2] Chickasaw,[3] Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee and some other Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands use the black drink in purification ceremonies. It was occasionally known as white drink because of the association of the color white with peace leaders in some Native cultures in the Southeast.[4]

Black drink is consumed to purify an individual by removing spiritual and physical contamination and, as such, is never taken casually. The preparation and protocols vary between tribes and ceremonial grounds. The full formula is not published or given to outsiders, but a prominent ingredient is the roasted leaves and stems of Ilex vomitoria (commonly known as yaupon holly), a plant native to the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. Black drink usually contains emetic herbs, which has been recorded as inducing vomiting.[5]

Preparation

According to the ethnohistorical record, the yaupon leaves and branches used for the black drink were traditionally picked as close to the time of its planned consumption as possible. After picking, historically they were lightly parched in a ceramic container over fire. The roasting increases the solubility in water of the caffeine, which is the same reason coffee beans are roasted.[6] After browning, they were boiled in large containers of water until the liquid reached a dark brown or black color, giving it its name. The liquid was then strained into containers to cool, until it was cool enough to not scald the skin, and drunk while still hot. Because caffeine is 30 times more soluble in boiling water than room temperature water, this heightened its effect. It was then consumed in a ritual manner. Its physiological effects are believed to be mainly those of massive doses of caffeine. Three to six cups of strong coffee is equal to 0.5 to 1.0 grams of caffeine; the black drink could have delivered at least this much and possibly up to 3.0 to 6.0 grams of caffeine.[7] Owen gives the caffeine content of coffee as between 1.01 and 1.42 percent [8] In comparison, Ilex vomitoria leaves contain 0.0038 to 0.2288 percent caffeine by weight according to experiments performed by Adam Edwards in 2002.[9] Similar methods of production were adopted by European colonists for the production of a drink that often shared the same names with Native names for the black drink but used for different, secular purposes.

While the general method of production is known, not all details of the preparation and ceremonial usage of the black drink are. The source of the emetic effect of black drink is not known and has been speculated upon by historians, archaeologists, and botanists. Some professionals believe it to be caused by the addition of poisonous button snakeroot.[10]

Contemporary preparation and usage of the black drink by Native Americans is less well documented. Online recipes for the black drink have been criticized by some Native Americans as potentially dangerous and potentially poisonous due those recipes leaving out key steps. The berries of the yaupon holly are poisonous.[11] Kidney failure is one possible outcome of consuming beverages containing holly leaves. Adam Edwards and Bradley Bennett tested stems, roots, and leaves of the yaupon. They found that the only possible toxic substance was theobromine, an alkaloid, but the amounts of the chemical were so low that a single gram of cocoa contained over 2,255 times more theobromine than yaupon.[12]

Archaeological accounts

Archaeologists have demonstrated the use of various kinds of black drink among Native American groups stretching back far into antiquity, possibly dating to Late Archaic times. During the Hopewell period, the shell cups known from later black drink rituals become common in high-status burials along with mortuary pottery and engraved stone and copper tablets. The significance of the shell cups may indicate the beginning of black drink ceremonialism. The fact that both the shells and the yaupon holly come from the same geographical location may indicate they were traded together in the Hopewell Interaction Sphere.[13] The appearance of shell cups can be used as a virtual marker for the advent of Hopewell Culture in many instances.[14] During the Mississippian culture period, the presence of items associated with the black drink ceremony had spread over most of the south, with many hundreds of examples from Etowah, Spiro, Moundville and Hiwassee Island.

Black drink at Cahokia

Archaeologists working at Cahokia, the largest Mississippian culture settlement located near the modern city of St. Louis, found distinctive and relatively rare pottery beakers dating from 1050 to 1250 CE. The beakers are small round pots with a handle on one side and a tiny lip on the opposing side. The surfaces of the unfired vessels was incised with motifs representing water and the underworld and resemble the whelk shells known to have been used for the consumption of the beverage during historic times. The inside of the vessels were found to be coated with a plant residue, which when tested was found to contain theobromine, caffeine and ursolic acid in the right proportions to have come from the Ilex vomitoria.[15] The presence of the black drink in the Greater Cahokia area at this early date pushes back the definitive use of the black drink by several centuries. The presence of the black drink hundreds of miles outside of its natural range on the East and Gulf coasts is evidence of a substantial trade network with the southeast, a trade that also involved sharks teeth and whelk shells.[16][17][18]

Shell cups

In historic accounts from the 16th and 17th century, the black drink is usually imbibed in rituals using a cup made of marine shell. Three main species of marine shells have been identified as being used as cups for the black drink, lightning whelk, emperor helmet, and the horse conch. The most common was the lightning whelk, which has a left-handed or sinistral spiral. The left-handed spiral may have held religious significance because of its association with dance and ritual. The center columnella, which runs longitudinally down the shell, would be removed, and the rough edges sanded down to make a dipper-like cup. The columnella would then be used as a pendant, a motif that shows up frequently in Southeastern Ceremonial Complex designs. In the archaeological record columnella pendants are usually found in conjunction with bi-lobed arrows, stone maces, earspools, and necklace beads(all of which are motifs identified with the falcon dancer/warrior/chunkey player mythological figure).[19] Artifacts made from these marine shells have been found as far north as Wisconsin and as far west as Oklahoma. Several examples of cups from Moundville and Spiro have been found to have rings of black residue in the bottoms, suggesting they were used for black drink rituals. Many examples of shell cups found in Mississippian culture mounds are engraved with S.E.C.C. imagery. A few examples portray what is theorized to be black drink rituals, including what some anthropologists have interpreted as vomit issuing from the mouths of mythological beings.[13]

Archaeological evidence for use in pre-Hispanic US Southwest and Mexican Northwest

Pottery samples recovered from sites in modern Southwestern United States and Northwestern Mexico have tested positive for the ratio of methylxanthines associated with those produced by Ilex vomitoria. The same study also identified methylxanthines ratios associated with Theobroma cacao. Neither plants are native to the areas from which the pottery samples were recovered, which suggests trading between areas where those plants are native. The chemical analysis also suggests a possible increase in drinks prepared from cacao after the year 1200, and a decrease in the use of drinks prepared from Ilex vomitoria. Freshwater shells from Texas and Arkansas have been recovered from Pueblo Bonito, which have been used as possible evidence for the trade of Ilex vomitoria from the east. There are also some stands of Ilex vomitoria in Mesoamerica, so the exact origins of the Ilex vomitoria used to prepare the drinks is currently unknown.[20]

Historical accounts

A number of tribes across the Southeastern United States use a form of the black drink in their ceremonies. Muscogee Creeks, Cherokees, Choctaws, Ais, Guale, Chickasaws, Chitimacha, Timucua and others are documented users of a type of black drink. Although rituals vary amongst the different tribes, there are some common traits among them. Black drink is most commonly drunk by men, who also prepare it, but there are some accounts of its preparation and use by women among some groups. Removal of tribes to areas outside the natural range of Ilex vomitoria has been partially responsible for a decline in the preparation of the black drink among present Native Americans.

Ais

In 1696, Jonathan Dickinson witnessed the use of a beverage brewed from the Yaupon Holly among the Ais of Florida. Dickinson later learned that the Spanish called the plant casseena. The Ais parched the leaves in a pot, and then boiled them. The resulting liquid was then transferred to a large bowl using a gourd that had a long neck with a small hole at the top, and a 2-inch-wide (51 mm) hole in the side. On the occasion Dickinson witnessed, he estimated that there were nearly three gallons of the beverage in the bowl. After the liquid had cooled, the chief was presented with a conch-shell of the beverage. The chief threw part of it on the ground as a blessing and drank the rest. The chief's associates were then served in turn. Lower status men, women, and children were not allowed to touch or taste the beverage. The chief and his associates sat drinking this brew, smoking and talking for most of the day. In the evening, the bowl that had held the beverage was covered with a skin to make a drum. The Ais, accompanied by the drum and some rattles, sang and danced until the middle of the night.[21]

Cherokee

Cherokee black drink is taken for purification at several traditional ceremonies. Made with emetics, the complete recipe is not shared with the public. The black drink induces vomiting for purification purposes. Other ritual medicinal beverages are also used in the ceremonies. Ilex vomitoria was not native to the traditional area controlled by the Cherokee before removal, but it was brought in to the area through trade and then transplanted.

Muscogean peoples

Among the Muscogee the black drink is called ássi. In the ceremonies of some cultures that use the drink, after its preparation it is passed out to the highest-status person first, then the next highest status, and so forth. During each person's turn to drink, ritual songs may be sung Yahola. Its use was traditionally limited to only adult men.[22] The ritual name Asi Yahola or Black Drink Singer is corrupted into English as Osceola).[23]

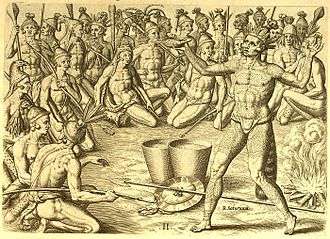

Timucua

Among the Timucua, a type of black drink was called cacina by the Spanish. The preparation and consumption of the drink were strictly limited to the community council house. Women (other than an occasional female chief) were normally excluded from the council house except for activities such as dances, but did prepare the cacina. In 1678 a bedridden cacica (a female chief) was given permission to brew and consume cacina in her house, on the condition that no one else could be present while she did so.[24]

Cassina or Yaupon Tea

After European contact with tribes in what is today the Southeastern United States, colonists began using the charred leaves of the yaupon holly to make a tea similar to the black drink, but without the ritual vomiting of it. Its use by colonists in Spanish Florida is documented as far back as 1615. An account from that year describes Spaniards as experiencing symptoms that would now be described as caffeine dependence due to daily consumption of what they called cacina or té del indio. The use of Ilex vomitoria by colonists for tea making and for medicinal uses in the Carolinas is documented by the early eighteenth century. In the English-speaking colonies, it was known variously as cassina, yaupon tea, Indian tea, Carolina tea, and Appalachian tea. It was commonly believed to be and used as a diuretic. By the late 1700s, yaupon tea was described as being more commonly used in North Carolina at breakfast than tea made with Camellia sinensis. In addition to using it on their own, Spanish and British colonist often drank black drink when engaging in discussions and treaties with Natives. Its preparation by British and Spanish colonists was nearly identical to the method of preparation used by their Native neighbors. Its use by colonists in French Louisiana is speculated to have occurred, but lacks documentation other than one source describing its medicinal uses from 1716.[25]

During the Civil War, yaupon tea was used as a substitute for coffee and tea throughout the South. Yaupon continued to be used in North Carolina for medicinal purposes and as a common drink until the late 1890s. At that point, its use was stigmatized because of its natural abundance as being a habit associated with rural poor people. By 1928 it was described as only being in common use by on Knotts Island, North Carolina. During the Interwar period the United States Department of Agriculture investigated the use of cassina tea as a substitute for coffee and tea. There were also a few attempts at the commercialization of cassina tea during that same period. By 1973 it was believed that cassina tea was only being served at the Pony Island Restaurant on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina.[25] In the early 2000s yaupon tea began witnessing a resurgence in its popularity, and can now be purchased online and at several historical sites related to Native Americans.

See also

- Mate (beverage) – a South American drink made from dried leaves of yerba mate, a species of holly.

- Mississippian culture

- Native American cuisine

- Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

Notes

- ↑ Hudson,, Charles, M (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. p. 59.

- ↑ Hudson,, Charles, M (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Hudson,, Charles, M (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Hudson,, Charles, M (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. pp. 2, 131.

- ↑ Gibbons, E (1964). Stalking the Blue-eyed Scallop. David McKay Company, Inc. ISBN 0-911469-05-2.

- ↑ Susan Budavari, ed. (1996). The Merck Index (12th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc. p. 1674.

- ↑ Hudson, Charles M. (1976). The Southeastern Indians. p. 226.

- ↑ Owen, Daiel, 2006. Coffee and Cafeine FAQ: How much caffeine there is in X coffee? Access at http://coffeefaq.com/site/node/23

- ↑ Edwards, Adam, 2002. morton/pdfs/a_edwards.pdf "Variation of caffeine and related alkaloids in Ilex vomitoria Ait. (Yaupon holly): A model of intraspecific alkaloid variation." Society for Economic Botany Julia F. Morton Award.

- ↑ Hudson, Charles M. (1976). The Southeastern Indians. pp. 4, 59, 62, 138, 140–141,.

- ↑ Perry, Mac (1990). Landscaping in Florida. Pineapple Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-1561640577. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ Edwards, Adam L.; Bennett, Bradley C. (2005). "Diversity of Methylxanthine Content in Ilex cassine L. and Ilex vomitoria Ait.: Assessing Sources of the North American Stimulant Cassina". Economic Botany. 59 (3): 275–285. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2005)059[0275:domcii]2.0.co;2.

- 1 2 Hudson, Charles M. (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. pp. 83–112.

- ↑ Griffin, James B. (1952). Culture Periods in Eastern United States Archaeology. University of Chicago Press. p. 360.

- ↑ Crown, Patricia L.; Emerson, Thomas E.; Gu, Jiyan; Hurst, W. Jeffery; Pauketat, Timothy R.; Ward, Timothy (28 August 2012). "Ritual Black Drink consumption at Cahokia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (35): 13944–13949. PMC 3435207

. PMID 22869743. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208404109.

. PMID 22869743. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208404109. - ↑ Diana Yates (2012-08-06). "Researchers find evidence of ritual use of 'black drink' at Cahokia". University of Illinois.

- ↑ Thomas H. Maugh II (2012-08-06). "Cahokia people had caffeine drink made from holly 900 years ago". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Charles Choi (2012-08-06). "Caffeinated 'Vomit Drink' Nauseated North America's First City". LiveScience.

- ↑ F. Kent Reilly and James Garber, eds. (2004). Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms. University of Texas Press. pp. 86–96. ISBN 978-0-292-71347-5.

- ↑ Crown, Patricia (2015). "Ritual drinks in the pre-Hispanic US Southwest and Mexican Northwest". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. HighWire Press. 112 (37): 11436–11442. PMC 4577151

. PMID 26372965. doi:10.1073/pnas.1511799112. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

. PMID 26372965. doi:10.1073/pnas.1511799112. Retrieved 22 March 2016. - ↑ Hudson, Charles M. (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Hudson, Charles M. (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. pp. 126–137.

- ↑ "Native Americans". Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ↑ Hann, John H. (1996). A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 2, 26, 90–91, 328. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- 1 2 Hudson, Charles M. (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. pp. 6–7, 150–155.

References

- Hudson, Charles M. (1979). Black Drink: A Native American Tea. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-0462-X

- Hale, Edwin Moses (1891). Ilex Cassine: The aboriginal North American tea : its history, distribution, and use among the native American Indians. Bulletin U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. Division of Botany.

- Andrews, Charles Mclean and Andrews, Evangeline Walker (1945). Jonathan Dickinson's Journal or, God's Protecting Providence. Being the Narrative of a Journey from Port Royal in Jamaica to Philadelphia between August 23, 1696 to April 1, 1697. Yale University Press. Reprinted 1981. Florida Classics Library.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black drink. |

- Crown, Patricia L.; Emerson, Thomas E.; Gu, Jiyan; Hurst, W. Jeffery; Pauketat, Timothy R.; Ward, Timothy (28 August 2012). "Ritual Black Drink consumption at Cahokia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (35): 13944–13949. PMC 3435207

. PMID 22869743. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208404109.

. PMID 22869743. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208404109. - Elizabeth Norton (2012-08-08). "'Black Drink' Tea Cup Discovered, Linked To Native American Ritual And Trade Network". Huffington Post.

- Photo of Cahokia mugs associated with black drink : John Shanks (2012-08-07). "Use of Caffeinated Drink in pre-Columbian North America". Sci-News.com.