Black Friday (1978)

| Black Friday | |

|---|---|

| Part of Iranian Revolution | |

| Location | Tehran, Iran |

| Date | 8 September 1978 (GMT+3.30) |

| Deaths | 88 |

| Perpetrators | Imperial Army of Iran |

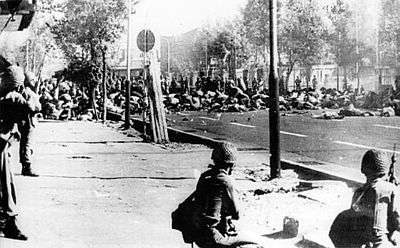

Black Friday (Persian: جمعه سیاه Jom'e-ye Siyāh) is the name given to 8 September 1978 (17 Shahrivar 1357 Iranian calendar)[1] because of the shootings in Jaleh Square (Persian: میدان ژاله Meydān-e Jāleh) in Tehran, Iran.[2][3] The deaths and the reaction to them has been described as a pivotal event in the Iranian Revolution when any "hope for compromise" between the protest movement and the Mohammad Reza Shah's regime was extinguished.[4]

Background and massacre

As protest against the Shah's rule continued during the spring and summer of 1978, the Iranian government declared martial law. On 8 September, thousands gathered in Tehran's Jaleh Square for a religious demonstration, unaware that the government had declared martial law the day before.[5] The soldiers ordered the crowd to disperse, but the order was ignored. Initially, it was thought that either because of this reason, or because of the fact that the protesters kept pushing towards the military, the military opened fire, killing and wounding dozens of people.

Black Friday is thought to have marked the point of no return for the revolution, and led to the abolition of Iran's monarchy less than a year later. It is also believed that Black Friday played a crucial role in further radicalizing the protest movement, uniting the opposition to the Shah and mobilized the masses. Initially opposition and western journalists claimed that the Iranian army massacred thousands of protesters.[6][7][8] The clerical leadership announced that "thousands have been massacred by Zionist troops."[9]

.jpg)

The events triggered protests that continued for another four months. The day after Black Friday, 9 September 1978, Hoveyda resigned as minister of court, although unrelated to the situation. A general strike in October shut down the petroleum industry that was essential to the administration's survival, "sealing the Shah's fate".[10] Continuation of protests ultimately led to Shah leaving from Iran in January 1979, clearing the way for the Iranian Revolution, led by the Ayatollah Khomeini.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17]

Aftermath

Initially, western media and opposition incorrectly reported "15,000 dead and wounded", despite reports by the Iranian government officials that 86 people died in Tehran during the whole day.[18] Michael Foucault, an influential French journalist and social theorist, first reported that 2000–3000 people died in the Jaleh Square and later he raised it to 4000 people dead.[6] The BBC's correspondent in Iran, Andrew Whitley, reported that hundreds died.[19]

According to Emad al-Din Baghi, a former researcher at the Martyrs Foundation (Bonyad Shahid, part of the current Iranian government, which compensates families of victims) hired "to make sense of the data" on those killed on Black Friday, 64 were killed in Jaleh Square on Black Friday, among them two females – one woman and a young girl. On the same day in other parts of the capital a total of 24 people died in clashes with martial law forces, among them one female, making the total casualties on the same day to 88 deaths.[6] Another source puts the Martyrs Foundation tabulation of dead at 84 during that day.[20]

The square's name was later changed to the Square of Martyrs (Maidan-e Shohada) by the Islamic republic.[8]

"Black Friday" in art

Persian language

In 1978 shortly after the massacre, the Iranian musician Hossein Alizadeh set Siavash Kasraie's poem about the event to music. Mohammad Reza Shajarian sang the piece "Jāleh Khun Shod" (Jaleh [Square] became bloody).[21]

English language

Nastaran Akhavan, one of the survivors, wrote the book Spared about the event. The book explains how the author was forced into a massive wave of thousands of angry protesters, who were later massacred by the Shah's military.[22] The 2016 adventure video game 1979 Revolution: Black Friday is based on the event. The game is directed by Navid Khonsari, who was a child at the time of the revolution and admitted he did not have a realistic view of what was taking place. Khonsari described creating the game as "[wanting] people to feel the passion and the elation of being in the revolution – of feeling that you could possibly make a change."[23]

See also

References and notes

- ↑ Abrahamian, Ervand. Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691101345. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Bashiriyeh, Hossein. The State and Revolution in Iran (RLE Iran D). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136820892. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Fischer, Michael M. J. Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299184735. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Ervand, History of Modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp. 160–1

- ↑ Bakhash, Schaul (1990). The Reign of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution. New York: Basic Books. p. 15.

- 1 2 3 "A Question of Numbers".

- ↑ "Islamic Revolution of Iran". Archived from the original on 31 October 2009.

- 1 2 "Black Friday". Archived from the original on 20 May 2003.

- ↑ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 223.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 189.

- ↑ The Persian Sphinx: Amir Abbas Hoveyda and the Riddle of the Iranian Revolution, Abbas Milani, pp. 292–293

- ↑ Seven Events That Made America America, Larry Schweikart, p.

- ↑ The Iranian Revolution of 1978/1979 and How Western Newspapers Reported It, Edgar Klüsener, p. 12

- ↑ Cultural History After Foucault, John Neubauer, p. 64

- ↑ Islam in the World Today: A Handbook of Politics, Religion, Culture, and Society By Werner Ende, Udo Steinbach, p. 264

- ↑ The A to Z of Iran, John H. Lorentz, p. 63

- ↑ Islam and Politics, John L. Esposito, p. 212

- ↑ Pahlavi, Mohammad Reza Shah (2003) Answer to History Irwin Pub, page 160, ISBN 978-0772012968

- ↑ "Black Friday Massacre – Iran (SEp. 8 1978)". Retrieved 7 June 2013

- ↑ E. Baqi, 'Figures for the Dead in the Revolution', Emruz, 30 July 2003, quoted in Abrahamian, Ervand, History of Modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp. 160–1

- ↑ Staff writers. "Jales became bloody". www.asriran.com. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ Akhavan, Nastaran (3 May 2012). "Spared". CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Retrieved 5 September 2016 – via Amazon.

- ↑ Holpuch, Amanda (14 November 2013). "Frag-counter revolutionaries: Iran 1979 revolution-based video game to launch". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.