Léon Croizat

Leon Camille Marius Croizat (July 16, 1894 – November 30, 1982) was a French-Italian scholar and botanist who developed an orthogenetic synthesis of evolution of biological form over space, in time, which he named Panbiogeography.

Life

Croizat was born in Torino, Italy to Vittorio Croizat (aka Victor Croizat) and Maria (Marie) Chaley, who had emigrated to Turin from Chambéry, France.[1] In spite of his great aptitude for the natural sciences, Leon studied and received a degree in Law from the University of Turin.

Croizat and his family (wife Lucia and two children) emgirated to the United States in 1924; an avid artist, Leon worked selling his artwork for several years, but could not succeed economically as a working artist after the stock market crash of 1929. During the 1930s, Croizat found a job identifying plants as part of a topographic inventory performed in the public parks of New York City. During his visits to the Bronx Botanical Gardens, he became acquainted with Dr. E. D. Merrill. When Merrill was appointed director of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University in 1936, he hired Leon as a technical assistant (in 1937.)[2]

Croizat became a prolific student and publisher, studying important aspects of the distribution and evolution of biological species. It was during this time that he began to formulate a novel current of thought in evolutionary theory, opposed in some respects to Darwinism, on the evolution and dispersal of biota over space, through time.

In 1947, Croizat moved to Venezuela after receiving an invitation from botanist Henri Pittier. Croizat then obtained a position in the Faculty of the Department of Agronomy at the Central University of Venezuela. In 1951 he was promoted and was awarded the title of Professor of Botany and Ecology at the University of the Andes, Venezuela. Between 1951 and 1952 he participated in the Franco-Venezuelan expedition to discover the sources of the Orinoco river. Croizat served with the expedition as a botanist with professor Jose Maria Cruxent.

During his time in Venezuela Croizat divorced his first wife. Croizat was later remarried to his second wife Catalina Krishaber, a Hungarian immigrant. In 1953 Croizat gave up all official academic positions to work full-time researching biology. Croizat and his wife Catalina lived in Caracas until 1976. In 1976 they took over as first directors of the “Jardin Botanico Xerofito” in Coro, a city approximately 400 kilometers West of Caracas. Jardin Botanico Xerofito was a botanical garden which they founded together. Croizat and Catalina worked for six years to establish Jardin Botanico Xerofito.

Croizat died at Coro on November 30, 1982 of a heart attack. During his life, Croizat has published around 300 scientific papers and seven books, amounting to more than 15,000 printed pages. He was honoured by Venezuela with the Henri Pittier Order of Merit in Conservation, and by the government of Italy with the Order of Merit. Several plant and animal species have been named after Croizat.[3][4][5]

Concepts

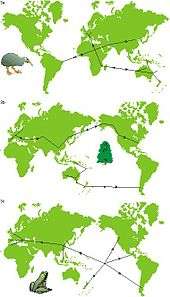

Panbiogeography is a discipline based on the analysis of patterns of distribution of organisms. The method analyzes biogeographic distributions through the drawing of tracks, and derives information from the form and orientation of those tracks. A track is a line connecting collection localities or disjunct areas of a particular taxon. Several individual tracks for unrelated groups of organisms form a generalized ('standard') track, where the individual components are relict fragments of an ancestral, more widespread biota fragmented by geological and/or climatic changes. A node arises from the intersection of two or more generalized tracks [7]

In graph theory a track is equated to a minimum spanning tree connecting all localities by the shortest path.[8]

To explain disjunct distributions, Croizat proposed the existence of broadly distributed ancestors that established its range during a period of mobilism, followed by a form-making process over a broad front. Disjunctions are explained as extinctions in the previously continuous range. Orthogenesis is a term used by Croizat, in his words "... in a pure mechanistic sense",[9] which refers to the fact that a variation in form is limited and constrained.[10] Croizat considered organism evolution as a function of time, space and form. Of these three essential factors, space is the one with which biogeography is primarily concerned. However space necessarily interplays with time and form, therefore the three factors are as one of biogeographic concern. Put another way, when evolution is considered to be guided by developmental constraints or by phylogenetic constraints, it is orthogenetic.[11]

Although authors belonging to the dispersalist establishment have dismissed Croizat's contributions, others have considered Croizat as one of the most original thinkers of modern comparative biology, whose contributions provided the foundation of a new synthesis between earth and life sciences. Panbiogeography became established as a productive research programme in historical biogeography [12]

Selected works

- Manual of Phytogeography or An Account of Plant Dispersal Throughout the World. Junk, The Hague, 1952. 696 pp.

- Panbiogeography or An Introductory Synthesis of Zoogeography, Phytogeography, Geology; with notes on evolution, systematics, ecology, anthropology, etc.. Published by the author, Caracas, 1958. 2755 pp.

- Principia Botanica or Beginnings of Botany. Published by the author, Caracas, 1961. 1821 pp.

- Space, Time, Form: The Biological Synthesis. Published by the author, Caracas, 1964. 881 pp

- Croizat L. 1982. Vicariance/vicariism, panbiogeography, "vicariance Biogeography," etc.: a clarification. Systematic Zoology 31: 291-304.

References

- ↑ Llorente, J., J. Morrone, A. Bueno, R. Pérez, A. Viloria. &: D. Espinosa: Historia del desarrollo y la recepción de las ideas panbíogeográficas de Léon Croizat, Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. 24(93): 549-577, 2000. ISSN 0370-3908.

- ↑ Llorente, J., J. Morrone, A. Bueno, R. Pérez, A. Viloria. &: D. Espinosa: Historia del desarrollo y la recepción de las ideas panbíogeográficas de Léon Croizat, Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. 24(93): 549-577, 2000. ISSN 0370-3908.

- ↑ Craw, R. (1984). Never a serious scientist: the life of Leon Croizat. Tuatara 27: 5-7

- ↑ Morrone, J.J. (2000). Entre el escarnio y el encomio: León Croizat y la panbiogeografía. Interciencia 25: 41-47.

- ↑ Llorente, J., Morrone, J., Bueno, A., Perez-Hernandez, R., Viloria, A. & Espinosa, D. (2000). Historia del desarrollo y la recepcion de las ideas panbiogeograficas de Leon Croizat. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales 24(93): 549-577

- ↑ IPNI. Croizat.

- ↑ Craw, R.C., Grehan, J.R. & Heads, M.J. (1999). Panbiogeography: Tracking the History of Life. Oxford University Press, New York.

- ↑ Page, R.D.M. (1987). Graphs and generalized tracks: quantifying Croizat’s panbiogeography. Systematic Zoology 36: 1-17.

- ↑ Croizat, L. (1964). Space, Time, Form: The Biological Synthesis. Published by the author, Caracas, p. 676

- ↑ Colacino, C. (1997). Leon Croizat's biogeography and macroevolution, or..."out of nothing, nothing comes". Philippine Scientist 34: 73-88

- ↑ Gray, Russell (1989). "Oppositions in panbiogeography: can the conflicts between selection, constraint, ecology, and history be resolved?". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 16: 787–806.

- ↑ Craw et al. (1999)

Further reading

- Morrone J.J. (2004). Homología Biogeográfica: las Coordenadas Espaciales de la Vida. México, DF: Cuadernos del Instituto de Biología 37, Instituto de Biología, UNAM.

- Morrone J.J. (2007) La Vita tra lo Spazio e il Tempo. Il Retaggio di Croizat e la Nuova Biogeografia. M. Zunino (Ed.). Palermo: Medical Books.

- Nelson, G. (1973). Comments on Leon Croizat's Biogeography. Systematic Zoology. Vol. 22, No. 3. pp. 312–320.

- Rosen, D. (1974). Space, Time, Form: The Biological Synthesis. Systematic Zoology, Vol. 23, No. 2. pp. 288–290.

External links

- Heads, M. & Craw, R. (1984). Bibliography of the scientific work of Leon Croizat, 1932-1982. Tuatara 27: 67-75

- Selected papers

- References on Panbiogeography

- Croizatia. Revista Multidisciplinaria de Ciencia y Tecnología

- Video documentary on Croizat