Biochemistry

| Part of a series on |

| Biochemistry |

|---|

|

| Key components |

| History and topics |

| Portals: Biology, MCB |

Biochemistry, sometimes called biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms.[1] By controlling information flow through biochemical signaling and the flow of chemical energy through metabolism, biochemical processes give rise to the complexity of life. Over the last decades of the 20th century, biochemistry has become so successful at explaining living processes that now almost all areas of the life sciences from botany to medicine to genetics are engaged in biochemical research.[2] Today, the main focus of pure biochemistry is on understanding how biological molecules give rise to the processes that occur within living cells,[3] which in turn relates greatly to the study and understanding of tissues, organs, and whole organisms[4]—that is, all of biology.

Biochemistry is closely related to molecular biology, the study of the molecular mechanisms by which genetic information encoded in DNA is able to result in the processes of life.[5] Depending on the exact definition of the terms used, molecular biology can be thought of as a branch of biochemistry, or biochemistry as a tool with which to investigate and study molecular biology.

Much of biochemistry deals with the structures, functions and interactions of biological macromolecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates and lipids, which provide the structure of cells and perform many of the functions associated with life.[6] The chemistry of the cell also depends on the reactions of smaller molecules and ions. These can be inorganic, for example water and metal ions, or organic, for example the amino acids, which are used to synthesize proteins.[7] The mechanisms by which cells harness energy from their environment via chemical reactions are known as metabolism. The findings of biochemistry are applied primarily in medicine, nutrition, and agriculture. In medicine, biochemists investigate the causes and cures of diseases.[8] In nutrition, they study how to maintain health wellness and study the effects of nutritional deficiencies.[9] In agriculture, biochemists investigate soil and fertilizers, and try to discover ways to improve crop cultivation, crop storage and pest control.

History

_and_Carl_Ferdinand_Cori.jpg)

At its broadest definition, biochemistry can be seen as a study of the components and composition of living things and how they come together to become life, and the history of biochemistry may therefore go back as far as the ancient Greeks.[10] However, biochemistry as a specific scientific discipline has its beginning sometime in the 19th century, or a little earlier, depending on which aspect of biochemistry is being focused on. Some argued that the beginning of biochemistry may have been the discovery of the first enzyme, diastase (today called amylase), in 1833 by Anselme Payen,[11] while others considered Eduard Buchner's first demonstration of a complex biochemical process alcoholic fermentation in cell-free extracts in 1897 to be the birth of biochemistry.[12][13] Some might also point as its beginning to the influential 1842 work by Justus von Liebig, Animal chemistry, or, Organic chemistry in its applications to physiology and pathology, which presented a chemical theory of metabolism,[10] or even earlier to the 18th century studies on fermentation and respiration by Antoine Lavoisier.[14][15] Many other pioneers in the field who helped to uncover the layers of complexity of biochemistry have been proclaimed founders of modern biochemistry, for example Emil Fischer for his work on the chemistry of proteins,[16] and F. Gowland Hopkins on enzymes and the dynamic nature of biochemistry.[17]

The term "biochemistry" itself is derived from a combination of biology and chemistry. In 1877, Felix Hoppe-Seyler used the term (biochemie in German) as a synonym for physiological chemistry in the foreword to the first issue of Zeitschrift für Physiologische Chemie (Journal of Physiological Chemistry) where he argued for the setting up of institutes dedicated to this field of study.[18][19] The German chemist Carl Neuberg however is often cited to have coined the word in 1903,[20][21][22] while some credited it to Franz Hofmeister.[23]

It was once generally believed that life and its materials had some essential property or substance (often referred to as the "vital principle") distinct from any found in non-living matter, and it was thought that only living beings could produce the molecules of life.[25] Then, in 1828, Friedrich Wöhler published a paper on the synthesis of urea, proving that organic compounds can be created artificially.[26] Since then, biochemistry has advanced, especially since the mid-20th century, with the development of new techniques such as chromatography, X-ray diffraction, dual polarisation interferometry, NMR spectroscopy, radioisotopic labeling, electron microscopy, and molecular dynamics simulations. These techniques allowed for the discovery and detailed analysis of many molecules and metabolic pathways of the cell, such as glycolysis and the Krebs cycle (citric acid cycle).

Another significant historic event in biochemistry is the discovery of the gene and its role in the transfer of information in the cell. This part of biochemistry is often called molecular biology.[27] In the 1950s, James D. Watson, Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins were instrumental in solving DNA structure and suggesting its relationship with genetic transfer of information.[28] In 1958, George Beadle and Edward Tatum received the Nobel Prize for work in fungi showing that one gene produces one enzyme.[29] In 1988, Colin Pitchfork was the first person convicted of murder with DNA evidence, which led to the growth of forensic science.[30] More recently, Andrew Z. Fire and Craig C. Mello received the 2006 Nobel Prize for discovering the role of RNA interference (RNAi), in the silencing of gene expression.[31]

Starting materials: the chemical elements of life

Around two dozen of the 92 naturally occurring chemical elements are essential to various kinds of biological life. Most rare elements on Earth are not needed by life (exceptions being selenium and iodine), while a few common ones (aluminum and titanium) are not used. Most organisms share element needs, but there are a few differences between plants and animals. For example, ocean algae use bromine, but land plants and animals seem to need none. All animals require sodium, but some plants do not. Plants need boron and silicon, but animals may not (or may need ultra-small amounts).

Just six elements—carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, calcium, and phosphorus—make up almost 99% of the mass of living cells, including those in the human body (see composition of the human body for a complete list). In addition to the six major elements that compose most of the human body, humans require smaller amounts of possibly 18 more.[32]

Biomolecules

The four main classes of molecules in biochemistry (often called biomolecules) are carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids.[33] Many biological molecules are polymers: in this terminology, monomers are relatively small micromolecules that are linked together to create large macromolecules known as polymers. When monomers are linked together to synthesize a biological polymer, they undergo a process called dehydration synthesis. Different macromolecules can assemble in larger complexes, often needed for biological activity.

Carbohydrates

The function of carbohydrates includes energy storage and providing structure. Sugars are carbohydrates, but not all carbohydrates are sugars. There are more carbohydrates on Earth than any other known type of biomolecule; they are used to store energy and genetic information, as well as play important roles in cell to cell interactions and communications.

The simplest type of carbohydrate is a monosaccharide, which among other properties contains carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, mostly in a ratio of 1:2:1 (generalized formula CnH2nOn, where n is at least 3). Glucose (C6H12O6) is one of the most important carbohydrates; others include fructose (C6H12O6), the sugar commonly associated with the sweet taste of fruits,[34][a] and deoxyribose (C5H10O4).

A monosaccharide can switch from the acyclic (open-chain) form to a cyclic form, through a nucleophilic addition reaction between the carbonyl group and one of the hydroxyls of the same molecule. The reaction creates a ring of carbon atoms closed by one bridging oxygen atom. The resulting molecule has an hemiacetal or hemiketal group, depending on whether the linear form was an aldose or a ketose. The reaction is easily reversed, yielding the original open-chain form.[35]

In these cyclic forms, the ring usually has 5 or 6 atoms. These forms are called furanoses and pyranoses, respectively — by analogy with furan and pyran, the simplest compounds with the same carbon-oxygen ring (although they lack the double bonds of these two molecules). For example, the aldohexose glucose may form a hemiacetal linkage between the hydroxyl on carbon 1 and the oxygen on carbon 4, yielding a molecule with a 5-membered ring, called glucofuranose. The same reaction can take place between carbons 1 and 5 to form a molecule with a 6-membered ring, called glucopyranose. Cyclic forms with a 7-atom ring (the same of oxepane), rarely encountered, are called heptoses.

When two monosaccharides undergo dehydration synthesis whereby a molecule of water is released, as two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom are lost from the two monosaccharides, the new molecule, consisting of two monosaccharides, is called a disaccharide and is conjoined together by a glycosidic or ether bond. The reverse reaction can also occur, using a molecule of water to split up a disaccharide and break the glycosidic bond; this is termed hydrolysis. The most well-known disaccharide is sucrose, ordinary sugar (in scientific contexts, called table sugar or cane sugar to differentiate it from other sugars). Sucrose consists of a glucose molecule and a fructose molecule joined together. Another important disaccharide is lactose, consisting of a glucose molecule and a galactose molecule. As most humans age, the production of lactase, the enzyme that hydrolyzes lactose back into glucose and galactose, typically decreases. This results in lactase deficiency, also called lactose intolerance.

When a few (around three to six) monosaccharides are joined, it is called an oligosaccharide (oligo- meaning "few"). These molecules tend to be used as markers and signals, as well as having some other uses.[36] Many monosaccharides joined together make a polysaccharide. They can be joined together in one long linear chain, or they may be branched. Two of the most common polysaccharides are cellulose and glycogen, both consisting of repeating glucose monomers. Examples are cellulose which is an important structural component of plant's cell walls, and glycogen, used as a form of energy storage in animals.

Sugar can be characterized by having reducing or non-reducing ends. A reducing end of a carbohydrate is a carbon atom that can be in equilibrium with the open-chain aldehyde (aldose) or keto form (ketose). If the joining of monomers takes place at such a carbon atom, the free hydroxy group of the pyranose or furanose form is exchanged with an OH-side-chain of another sugar, yielding a full acetal. This prevents opening of the chain to the aldehyde or keto form and renders the modified residue non-reducing. Lactose contains a reducing end at its glucose moiety, whereas the galactose moiety forms a full acetal with the C4-OH group of glucose. Saccharose does not have a reducing end because of full acetal formation between the aldehyde carbon of glucose (C1) and the keto carbon of fructose (C2).

Lipids

Lipids comprises a diverse range of molecules and to some extent is a catchall for relatively water-insoluble or nonpolar compounds of biological origin, including waxes, fatty acids, fatty-acid derived phospholipids, sphingolipids, glycolipids, and terpenoids (e.g., retinoids and steroids). Some lipids are linear aliphatic molecules, while others have ring structures. Some are aromatic, while others are not. Some are flexible, while others are rigid.[39]

Lipids are usually made from one molecule of glycerol combined with other molecules. In triglycerides, the main group of bulk lipids, there is one molecule of glycerol and three fatty acids. Fatty acids are considered the monomer in that case, and may be saturated (no double bonds in the carbon chain) or unsaturated (one or more double bonds in the carbon chain).[40]

Most lipids have some polar character in addition to being largely nonpolar. In general, the bulk of their structure is nonpolar or hydrophobic ("water-fearing"), meaning that it does not interact well with polar solvents like water. Another part of their structure is polar or hydrophilic ("water-loving") and will tend to associate with polar solvents like water. This makes them amphiphilic molecules (having both hydrophobic and hydrophilic portions). In the case of cholesterol, the polar group is a mere -OH (hydroxyl or alcohol). In the case of phospholipids, the polar groups are considerably larger and more polar, as described below.[41]

Lipids are an integral part of our daily diet. Most oils and milk products that we use for cooking and eating like butter, cheese, ghee etc., are composed of fats. Vegetable oils are rich in various polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). Lipid-containing foods undergo digestion within the body and are broken into fatty acids and glycerol, which are the final degradation products of fats and lipids. Lipids, especially phospholipids, are also used in various pharmaceutical products, either as co-solubilisers (e.g., in parenteral infusions) or else as drug carrier components (e.g., in a liposome or transfersome).

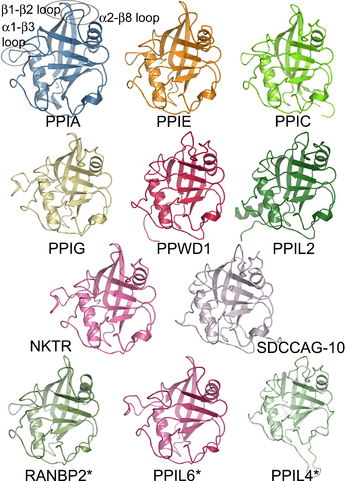

Proteins

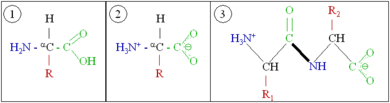

Proteins are very large molecules – macro-biopolymers – made from monomers called amino acids. An amino acid consists of a carbon atom bound to four groups. One is an amino group, —NH2, and one is a carboxylic acid group, —COOH (although these exist as —NH3+ and —COO− under physiologic conditions). The third is a simple hydrogen atom. The fourth is commonly denoted "—R" and is different for each amino acid. There are 20 standard amino acids, each containing a carboxyl group, an amino group, and a side-chain (known as an "R" group). The "R" group is what makes each amino acid different, and the properties of the side-chains greatly influence the overall three-dimensional conformation of a protein. Some amino acids have functions by themselves or in a modified form; for instance, glutamate functions as an important neurotransmitter. Amino acids can be joined via a peptide bond. In this dehydration synthesis, a water molecule is removed and the peptide bond connects the nitrogen of one amino acid's amino group to the carbon of the other's carboxylic acid group. The resulting molecule is called a dipeptide, and short stretches of amino acids (usually, fewer than thirty) are called peptides or polypeptides. Longer stretches merit the title proteins. As an example, the important blood serum protein albumin contains 585 amino acid residues.[42]

Some proteins perform largely structural roles. For instance, movements of the proteins actin and myosin ultimately are responsible for the contraction of skeletal muscle. One property many proteins have is that they specifically bind to a certain molecule or class of molecules—they may be extremely selective in what they bind. Antibodies are an example of proteins that attach to one specific type of molecule. In fact, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which uses antibodies, is one of the most sensitive tests modern medicine uses to detect various biomolecules. Probably the most important proteins, however, are the enzymes. Virtually every reaction in a living cell requires an enzyme to lower the activation energy of the reaction. These molecules recognize specific reactant molecules called substrates; they then catalyze the reaction between them. By lowering the activation energy, the enzyme speeds up that reaction by a rate of 1011 or more; a reaction that would normally take over 3,000 years to complete spontaneously might take less than a second with an enzyme. The enzyme itself is not used up in the process, and is free to catalyze the same reaction with a new set of substrates. Using various modifiers, the activity of the enzyme can be regulated, enabling control of the biochemistry of the cell as a whole.

The structure of proteins is traditionally described in a hierarchy of four levels. The primary structure of a protein simply consists of its linear sequence of amino acids; for instance, "alanine-glycine-tryptophan-serine-glutamate-asparagine-glycine-lysine-…". Secondary structure is concerned with local morphology (morphology being the study of structure). Some combinations of amino acids will tend to curl up in a coil called an α-helix or into a sheet called a β-sheet; some α-helixes can be seen in the hemoglobin schematic above. Tertiary structure is the entire three-dimensional shape of the protein. This shape is determined by the sequence of amino acids. In fact, a single change can change the entire structure. The alpha chain of hemoglobin contains 146 amino acid residues; substitution of the glutamate residue at position 6 with a valine residue changes the behavior of hemoglobin so much that it results in sickle-cell disease. Finally, quaternary structure is concerned with the structure of a protein with multiple peptide subunits, like hemoglobin with its four subunits. Not all proteins have more than one subunit.[43]

Ingested proteins are usually broken up into single amino acids or dipeptides in the small intestine, and then absorbed. They can then be joined to make new proteins. Intermediate products of glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway can be used to make all twenty amino acids, and most bacteria and plants possess all the necessary enzymes to synthesize them. Humans and other mammals, however, can synthesize only half of them. They cannot synthesize isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine. These are the essential amino acids, since it is essential to ingest them. Mammals do possess the enzymes to synthesize alanine, asparagine, aspartate, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine, the nonessential amino acids. While they can synthesize arginine and histidine, they cannot produce it in sufficient amounts for young, growing animals, and so these are often considered essential amino acids.

If the amino group is removed from an amino acid, it leaves behind a carbon skeleton called an α-keto acid. Enzymes called transaminases can easily transfer the amino group from one amino acid (making it an α-keto acid) to another α-keto acid (making it an amino acid). This is important in the biosynthesis of amino acids, as for many of the pathways, intermediates from other biochemical pathways are converted to the α-keto acid skeleton, and then an amino group is added, often via transamination. The amino acids may then be linked together to make a protein.[44]

A similar process is used to break down proteins. It is first hydrolyzed into its component amino acids. Free ammonia (NH3), existing as the ammonium ion (NH4+) in blood, is toxic to life forms. A suitable method for excreting it must therefore exist. Different tactics have evolved in different animals, depending on the animals' needs. Unicellular organisms, of course, simply release the ammonia into the environment. Likewise, bony fish can release the ammonia into the water where it is quickly diluted. In general, mammals convert the ammonia into urea, via the urea cycle.[45]

In order to determine whether two proteins are related, or in other words to decide whether they are homologous or not, scientists use sequence-comparison methods. Methods like sequence alignments and structural alignments are powerful tools that help scientists identify homologies between related molecules.[46] The relevance of finding homologies among proteins goes beyond forming an evolutionary pattern of protein families. By finding how similar two protein sequences are, we acquire knowledge about their structure and therefore their function.

Nucleic acids

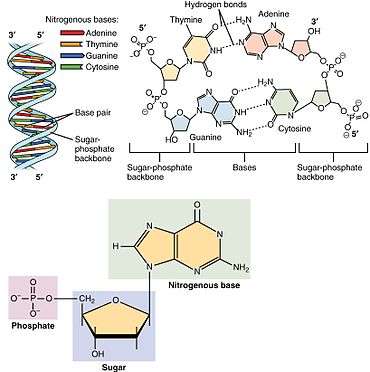

Nucleic acids, so called because of their prevalence in cellular nuclei, is the generic name of the family of biopolymers. They are complex, high-molecular-weight biochemical macromolecules that can convey genetic information in all living cells and viruses.[2] The monomers are called nucleotides, and each consists of three components: a nitrogenous heterocyclic base (either a purine or a pyrimidine), a pentose sugar, and a phosphate group.[47]

The most common nucleic acids are deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA).[48] The phosphate group and the sugar of each nucleotide bond with each other to form the backbone of the nucleic acid, while the sequence of nitrogenous bases stores the information. The most common nitrogenous bases are adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, and uracil. The nitrogenous bases of each strand of a nucleic acid will form hydrogen bonds with certain other nitrogenous bases in a complementary strand of nucleic acid (similar to a zipper). Adenine binds with thymine and uracil; thymine binds only with adenine; and cytosine and guanine can bind only with one another.

Aside from the genetic material of the cell, nucleic acids often play a role as second messengers, as well as forming the base molecule for adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the primary energy-carrier molecule found in all living organisms.[49] Also, the nitrogenous bases possible in the two nucleic acids are different: adenine, cytosine, and guanine occur in both RNA and DNA, while thymine occurs only in DNA and uracil occurs in RNA.

Metabolism

Carbohydrates as energy source

Glucose is the major energy source in most life forms. For instance, polysaccharides are broken down into their monomers (glycogen phosphorylase removes glucose residues from glycogen). Disaccharides like lactose or sucrose are cleaved into their two component monosaccharides.

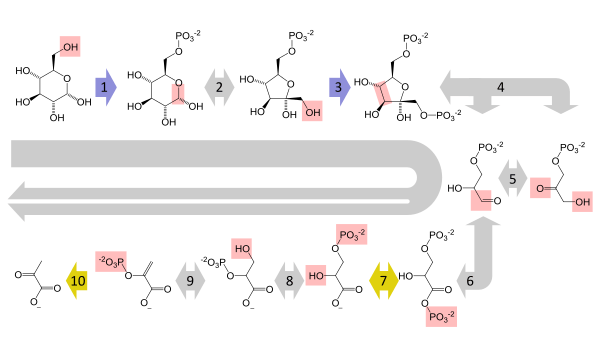

Glycolysis (anaerobic)

Glucose is mainly metabolized by a very important ten-step pathway called glycolysis, the net result of which is to break down one molecule of glucose into two molecules of pyruvate. This also produces a net two molecules of ATP, the energy currency of cells, along with two reducing equivalents of converting NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide: oxidised form) to NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide: reduced form). This does not require oxygen; if no oxygen is available (or the cell cannot use oxygen), the NAD is restored by converting the pyruvate to lactate (lactic acid) (e.g., in humans) or to ethanol plus carbon dioxide (e.g., in yeast). Other monosaccharides like galactose and fructose can be converted into intermediates of the glycolytic pathway.[50]

Aerobic

In aerobic cells with sufficient oxygen, as in most human cells, the pyruvate is further metabolized. It is irreversibly converted to acetyl-CoA, giving off one carbon atom as the waste product carbon dioxide, generating another reducing equivalent as NADH. The two molecules acetyl-CoA (from one molecule of glucose) then enter the citric acid cycle, producing two more molecules of ATP, six more NADH molecules and two reduced (ubi)quinones (via FADH2 as enzyme-bound cofactor), and releasing the remaining carbon atoms as carbon dioxide. The produced NADH and quinol molecules then feed into the enzyme complexes of the respiratory chain, an electron transport system transferring the electrons ultimately to oxygen and conserving the released energy in the form of a proton gradient over a membrane (inner mitochondrial membrane in eukaryotes). Thus, oxygen is reduced to water and the original electron acceptors NAD+ and quinone are regenerated. This is why humans breathe in oxygen and breathe out carbon dioxide. The energy released from transferring the electrons from high-energy states in NADH and quinol is conserved first as proton gradient and converted to ATP via ATP synthase. This generates an additional 28 molecules of ATP (24 from the 8 NADH + 4 from the 2 quinols), totaling to 32 molecules of ATP conserved per degraded glucose (two from glycolysis + two from the citrate cycle).[51] It is clear that using oxygen to completely oxidize glucose provides an organism with far more energy than any oxygen-independent metabolic feature, and this is thought to be the reason why complex life appeared only after Earth's atmosphere accumulated large amounts of oxygen.

Gluconeogenesis

In vertebrates, vigorously contracting skeletal muscles (during weightlifting or sprinting, for example) do not receive enough oxygen to meet the energy demand, and so they shift to anaerobic metabolism, converting glucose to lactate. The liver regenerates the glucose, using a process called gluconeogenesis. This process is not quite the opposite of glycolysis, and actually requires three times the amount of energy gained from glycolysis (six molecules of ATP are used, compared to the two gained in glycolysis). Analogous to the above reactions, the glucose produced can then undergo glycolysis in tissues that need energy, be stored as glycogen (or starch in plants), or be converted to other monosaccharides or joined into di- or oligosaccharides. The combined pathways of glycolysis during exercise, lactate's crossing via the bloodstream to the liver, subsequent gluconeogenesis and release of glucose into the bloodstream is called the Cori cycle.[52]

Relationship to other "molecular-scale" biological sciences

Researchers in biochemistry use specific techniques native to biochemistry, but increasingly combine these with techniques and ideas developed in the fields of genetics, molecular biology and biophysics. There has never been a hard-line among these disciplines in terms of content and technique. Today, the terms molecular biology and biochemistry are nearly interchangeable. The following figure is a schematic that depicts one possible view of the relationship between the fields:

- Biochemistry is the study of the chemical substances and vital processes occurring in living organisms. Biochemists focus heavily on the role, function, and structure of biomolecules. The study of the chemistry behind biological processes and the synthesis of biologically active molecules are examples of biochemistry.

- Genetics is the study of the effect of genetic differences on organisms. Often this can be inferred by the absence of a normal component (e.g., one gene), in the study of "mutants" – organisms with a changed gene that leads to the organism being different with respect to the so-called "wild type" or normal phenotype. Genetic interactions (epistasis) can often confound simple interpretations of such "knock-out" or "knock-in" studies.

- Molecular biology is the study of molecular underpinnings of the process of replication, transcription and translation of the genetic material. The central dogma of molecular biology where genetic material is transcribed into RNA and then translated into protein, despite being an oversimplified picture of molecular biology, still provides a good starting point for understanding the field. This picture, however, is undergoing revision in light of emerging novel roles for RNA.[53]

- Chemical biology seeks to develop new tools based on small molecules that allow minimal perturbation of biological systems while providing detailed information about their function. Further, chemical biology employs biological systems to create non-natural hybrids between biomolecules and synthetic devices (for example emptied viral capsids that can deliver gene therapy or drug molecules).[54]

See also

Lists

See also

- Biochemistry (journal)

- Biological Chemistry (journal)

- Biophysics

- Chemical ecology

- Computational biomodeling

- EC number

- Hypothetical types of biochemistry

- International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Metabolome

- Metabolomics

- Molecular biology

- Molecular medicine

- Plant biochemistry

- Proteolysis

- Small molecule

- Structural biology

- TCA cycle

Notes

a. ^ Fructose is not the only sugar found in fruits. Glucose and sucrose are also found in varying quantities in various fruits, and indeed sometimes exceed the fructose present. For example, 32% of the edible portion of date is glucose, compared with 23.70% fructose and 8.20% sucrose. However, peaches contain more sucrose (6.66%) than they do fructose (0.93%) or glucose (1.47%).[55]

References

- ↑ "Biochemistry". acs.org.

- 1 2 Voet (2005), p. 3.

- ↑ Karp (2009), p. 2.

- ↑ Miller (2012), p. 62.

- ↑ Astbury (1961), p. 1124.

- ↑ Eldra (2007), p. 45.

- ↑ Marks (2012), Chapter 14.

- ↑ Finkel (2009), pp. 1–4.

- ↑ UNICEF (2010), pp. 61, 75.

- 1 2 Helvoort (2000), p. 81.

- ↑ Hunter (2000), p. 75.

- ↑ Hamblin (2005), p. 26.

- ↑ Hunter (2000), pp. 96–98.

- ↑ Berg (1980), pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Holmes (1987), p. xv.

- ↑ Feldman (2001), p. 206.

- ↑ Rayner-Canham (2005), p. 136.

- ↑ Ziesak (1999), p. 169.

- ↑ Kleinkauf (1988), p. 116.

- ↑ Ben-Menahem (2009), p. 2982.

- ↑ Amsler (1986), p. 55.

- ↑ Horton (2013), p. 36.

- ↑ Kleinkauf (1988), p. 43.

- ↑ Edwards (1992), pp. 1161–1173.

- ↑ Fiske (1890), pp. 419–20.

- ↑ Kauffman (2001), pp. 121–133.

- ↑ Tropp (2012), p. 2.

- ↑ Tropp (2012), pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Krebs (2012), p. 32.

- ↑ Butler (2009), p. 5.

- ↑ Chandan (2007), pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Nielsen (1999), pp. 283–303.

- ↑ Slabaugh (2007), pp. 3–6.

- ↑ Whiting (1970), pp. 1–31.

- ↑ Voet (2005), pp. 358–359.

- ↑ Varki (1999), p. 17.

- ↑ Stryer (2007), p. 328.

- ↑ Voet (2005), Ch. 12 Lipids and Membranes.

- ↑ Fromm and Hargrove (2012), pp. 22–27.

- ↑ Voet (2005), pp. 382–385.

- ↑ Voet (2005), pp. 385–389.

- ↑ Metzler (2001), p. 58.

- ↑ Fromm and Hargrove (2012), pp. 35–51.

- ↑ Fromm and Hargrove (2012), pp. 279–292.

- ↑ Sherwood (2012), p. 558.

- ↑ Fariselli (2007), pp. 78–87.

- ↑ Saenger (1984), p. 84.

- ↑ Tropp (2012), pp. 5–9.

- ↑ Knowles (1980), pp. 877–919.

- ↑ Fromm and Hargrove (2012), pp. 163–180.

- ↑ Voet (2005), Ch. 17 Glycolysis.

- ↑ Fromm and Hargrove (2012), pp. 183–194.

- ↑ Ulveling (2011), pp. 633–644.

- ↑ Rojas-Ruiz (2011), pp. 2672–2687.

- ↑ Whiting, G.C. (1970), p. 5.

Cited literature

- Amsler, Mark (1986). The Languages of Creativity: Models, Problem-solving, Discourse. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0874132809.

- Astbury, W.T. (1961). "Molecular Biology or Ultrastructural Biology?" (PDF). Nature. 190 (4781): 1124. PMID 13684868. doi:10.1038/1901124a0. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- Ben-Menahem, Ari (2009). Historical Encyclopedia of Natural and Mathematical Sciences. Springer. p. 2982. ISBN 978-3-540-68831-0.

- Burton, Feldman (2001). The Nobel Prize: A History of Genius, Controversy, and Prestige. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1559705929.

- Butler, John M. (2009). Fundamentals of Forensic DNA Typing. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-096176-7.

- Chandan, Sen K.; Sashwati Roy (2007). "miRNA: Licensed to kill the messenger". DNA Cell Biology. 26 (4). PMID 17465885. doi:10.1089/dna.2006.0567.

- Clarence, Peter Berg (1980). "The University of Iowa and Biochemistry from Their Beginnings". ISBN 9780874140149.

- Edwards K.J.; Brown D.G.; Spink, N.; Skelly J.V.; Neidle S. (1992). "Molecular structure of the B-DNA dodecamer d(CGCAAATTTGCG)2. An examination of propeller twist and minor-groove water structure at 2.2 A resolution". J.Mol.Biol. 226: 1161–1173. PMID 1518049.

- Eldra P. Solomon; Linda R. Berg; Diana W. Martin (2007). Biology, 8th Edition, International Student Edition. Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0495317142.

- Fariselli, Piero; Rossi, Ivan; Capriotti, Emidio; Casadio, Rita (2007). "The WWWH of remote homolog detection: the state of the art". Briefings in Bioinformatics. 8 (2). PMID 17003074. doi:10.1093/bib/bbl032.

- Fiske, John (1890). Outlines of Cosmic Philosophy Based on the Doctrines of Evolution, with Criticisms on the Positive Philosophy, Volume 1. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Finkel, Richard; Cubeddu, Luigi; Clark, Michelle (2009). Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Pharmacology (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7155-9.

- Krebs, Jocelyn E.; Goldstein, Elliott S.; Lewin, Benjamin; Kilpatrick, Stephen T. (2012). Essential Genes. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4496-1265-8.

- Fromm, Herbert J.; Hargrove, Mark (2012). Essentials of Biochemistry. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-19623-2.

- Hamblin, Jacob Darwin (2005). Science in the Early Twentieth Century: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-665-7.

- Helvoort, Ton van (2000). Arne Hessenbruch, ed. Reader's Guide to the History of Science. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishing. ISBN 188496429X.

- Holmes, Frederic Lawrence (1987). Lavoisier and the Chemistry of Life: An Exploration of Scientific Creativity. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299099848.

- Horton, Derek, ed. (28 November 2013). Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry, Volume 70. Academic Press. ASIN B00H7E78BG.

- Hunter, Graeme K. (2000). Vital Forces: The Discovery of the Molecular Basis of Life. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-361811-5.

- Karp, Gerald (19 October 2009). Cell and Molecular Biology: Concepts and Experiments. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470483374.

- Kauffman, G.B.; Chooljian, S.H. (2001). "Friedrich Wöhler (1800–1882), on the bicentennial of his birth". The Chemical Educator. 6 (2). doi:10.1007/s00897010444a.

- Kleinkauf, Horst; Döhren, Hans von; Jaenicke Lothar (1988). The Roots of Modern Biochemistry: Fritz Lippmann's Squiggle and its Consequences. Walter de Gruyter & Co. p. 116. ISBN 9783110852455.

- Knowles JR (1980). "Enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer reactions". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 49: 877–919. PMID 6250450. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004305.

- Metzler, David Everett; Metzler, Carol M. (2001). Biochemistry: The Chemical Reactions of Living Cells. 1. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-492540-3.

- Miller G; Spoolman Scott (2012). Environmental Science - Biodiversity Is a Crucial Part of the Earth's Natural Capital. Cengage Learning. ISBN 1-133-70787-4. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- Nielsen, Forrest H. (1999). Maurice E. Shils ... et al.., eds. Ultratrace minerals; Modern nutrition in health and disease. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. pp. 283–303.

- Peet, Alisa (2012). Marks, Allan; Lieberman Michael A., eds. Marks' Basic Medical Biochemistry (Lieberman, Marks's Basic Medical Biochemistry) (4th ed.). ISBN 160831572X.

- Rayner-Canham, Marelene F.; Rayner-Canham, Marelene; Rayner-Canham, Geoffrey (2005). Women in Chemistry: Their Changing Roles from Alchemical Times to the Mid-Twentieth Century. Chemical Heritage Foundation. ISBN 978-0941901277.

- Rojas-Ruiz, Fernando A; Vargas-Méndez, Leonor; Kouznetsov, Vladimir V (2011). "Challenges and Perspectives of Chemical Biology, a Successful Multidisciplinary Field of Natural Sciences". Molecules. 16: 2672–2687. ISSN 1420-3049. doi:10.3390/molecules16032672. Archived from the original on December 5, 2015.

- Saenger, Wolfram (1984). Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90762-9.

- Slabaugh, Michael R.; Seager, Spencer L. (2013). Organic and Biochemistry for Today (6th ed.). Pacific Grove: Brooks Cole. ISBN 1133605141.

- Sherwood, Lauralee; Klandorf, Hillar; Yancey, Paul H. (2012). Animal Physiology: From Genes to Organisms. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-8400-6865-1.

- Stryer L, Berg JM, Tymoczko JL (2007). Biochemistry (6th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-8724-2.

- Tropp, Burton E. (2012). Molecular Biology (4th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-4496-0091-4.

- UNICEF (2010). Facts for life (PDF) (4th ed.). New York: United Nations Children's Fund. ISBN 978-92-806-4466-1.

- Ulveling, Damien; Francastel, Claire; Hubé, Florent (2011). "When one is better than two: RNA with dual functions". Biochimie. 93 (4). PMID 21111023. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2010.11.004.

- Varki A, Cummings R, Esko J, Jessica F, Hart G, Marth J (1999). Essentials of glycobiology. Essentials of glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-560-9.

- Voet, D; Voet, JG (2005). Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 9780471193500. Archived from the original on September 11, 2007.

- Whiting, G.C (1970). "Sugars". In A.C. Hulme. The Biochemistry of Fruits and their Products. Volume 1. London & New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0123612012.

- Ziesak, Anne-Katrin; Cram Hans-Robert (18 October 1999). Walter de Gruyter Publishers, 1749-1999. Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 978-3110167412.

Further reading

- Keith Roberts, Martin Raff, Bruce Alberts, Peter Walter, Julian Lewis and Alexander Johnson, Molecular Biology of the Cell

- Fruton, Joseph S. Proteins, Enzymes, Genes: The Interplay of Chemistry and Biology. Yale University Press: New Haven, 1999. ISBN 0-300-07608-8

- Kohler, Robert. From Medical Chemistry to Biochemistry: The Making of a Biomedical Discipline. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

External links

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Biochemistry |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Biochemistry. |

| At Wikiversity, you can learn more and teach others about Biochemistry at the Department of Biochemistry |

- "Biochemical Society".

- The Virtual Library of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Cell Biology

- Biochemistry, 5th ed. Full text of Berg, Tymoczko, and Stryer, courtesy of NCBI.

- SystemsX.ch - The Swiss Initiative in Systems Biology

- Full text of Biochemistry by Kevin and Indira, an introductory biochemistry textbook.