Biogeographic realm

A biogeographic realm or ecozone is the broadest biogeographic division of the Earth's land surface, based on distributional patterns of terrestrial organisms. They are subdivided in ecoregions, which are classified in biomes or habitat types.

The realms delineate large areas of the Earth's surface within which organisms have been evolving in relative isolation over long periods of time, separated from one another by geographic features, such as oceans, broad deserts, or high mountain ranges, that constitute barriers to migration. As such, biogeographic realms designations are used to indicate general groupings of organisms based on their shared biogeography. Biogeographic realms correspond to the floristic kingdoms of botany or zoogeographic regions of zoology.

Biogeographic realms are characterized by the evolutionary history of the organisms they contain. They are distinct from biomes, also known as major habitat types, which are divisions of the Earth's surface based on life form, or the adaptation of animals, fungi, micro-organisms and plants to climatic, soil, and other conditions. Biomes are characterized by similar climax vegetation. Each realm may include a number of different biomes. A tropical moist broadleaf forest in Central America, for example, may be similar to one in New Guinea in its vegetation type and structure, climate, soils, etc., but these forests are inhabited by animals, fungi, micro-organisms and plants with very different evolutionary histories.

The patterns of distribution of living organisms in the world's biogeographic realms were shaped by the process of plate tectonics, which has redistributed the world's land masses over geological history.

Concept history

The "biogeographic realms" of Udvardy (1975) were defined based on taxonomic composition. The rank corresponds more or less to the floristic kingdoms and zoogeographic regions.[1]

The usage of the term "ecozone" is more variable. It was used originally in stratigraphy (Vella, 1962, Hedberg, 1971). In Canadian literature, the term was used by Wiken (1986) in macro level land classification, with geographic criteria (see Ecozones of Canada).[2][3] Later, Schültz (1988) would use it with ecological and physiognomical criteria, in a way similar to the concept of biome.[4]

In the Global 200/WWF scheme (Olson & Dinerstein, 1998), originally the term "biogeographic realm" in Udvardy sense was used.[5] However, in a scheme of BBC, it was replaced by the term "ecozone".[6]

Terrestrial biogeographic realms

Udvardy (1975) biogeographic realms

The hierarchy of the scheme is (with early replaced terms in parenthesis):[1]

- biogeographic realm (= biogeographic regions and subregions), with 8 categories

- biogeographic province (= biotic province), with 193 categories, each characterized by a major biome or biome-complex

- biome, with 14 types

- biogeographic province (= biotic province), with 193 categories, each characterized by a major biome or biome-complex

The realms and provinces of the scheme are:

- 1.1.2 Sitkan province

- 1.2.2. Oregonian province

- 1.3.3 Yukon taiga province

- 1.4.3 Canadian taiga province

- 1.5.5. Eastern forest province

- 1.6.5 Austroriparian province

- 1.7.6 Californian province

- 1.8.7 Sonoran province

- 1.9.7 Chihuahuan province

- 1.10.7 Tamaulipan province

- 1.11.8 Great Basin province

- 1.12.9 Aleutian Islands province

- 1.13.9 Alaskan tundra province

- 1.14.9 Canadian tundra province

- 1.15.9 Arctic Archipelago province

- 1.16.9 Greenland tundra province

- 1.17.9 Arctic desert and icecap province

- 1.18.11 Grasslands province

- 1.19.12 Rocky Mountains province

- 1.20.12 Sierra-Cascade province

- 1.21.12 Madrean-Cordilleran province

- 1.22.14 Great Lakes province

- 2.1.2. Chinese Subtropical Forest province

- 2.2.2 Japanese Evergreen Forest province (= Japanese Subtropical Forest)

- 2.3.3 West Eurasian Taiga province

- 2.4.3 East Siberian Taiga province

- 2.5.5 Icelandian province (= Iceland)

- 2.6.5 Subarctic Birchwoods province

- 2.7.5 Kamchatkan province

- 2.8.5 British Islands province (= British + Irish Forest)

- 2.9.5 Atlantic province (West European Forest, in part)

- 2.10.5 Boreonemoral province (Baltic Lowland, in part)

- 2.11.5 Middle European Forest province (= East European Mixed Forest)

- 2.12.5 Pannonian province (= Danubian Steppe)

- 2.13.5 West Anatolian province

- 2.14.5 Manchu-Japanese Mixed Forest province (= Manchurian + Japanese Mixed Forest)

- 2.15.6 Oriental Deciduous Forest province

- 2.16.6 Iberian Highlands province

- 2.17.7 Mediterranean Sclerophyll province

- 2.18.7 Sahara province

- 2.19.7 Arabian Desert province (= Arabia)

- 2.20.8 Anatolian-Iranian Desert province (= Turkish-Iranian Scrub-steppe)

- 2.21.8 Turanian province (= Kazakh Desert Scrub-steppe)

- 2.22.8 Takla-Makan-Gobi Desert steppe province

- 2.23.8 Tibetan province

- 2.24.9 Iranian Desert province

- 2.25.9 Arctic Desert province

- 2.26.9 Higharctic Tundra province (= Eurasian Tundra, in part)

- 2.27.11 Lowarctic Tundra province (= Eurasian Tundra, in part)

- 2.28.11 Atlas Steppe province (= Atlas Highlands)

- 2.29.11 Pontian Steppe province (= Ukraine-Kazakh Steppe)

- 2.30.11 Mongolian-Manchurian Steppe province (= Gobi + Manchurian Steppe)

- 2.31.12 Scottish Highlands Highlands province

- 2.32.12 Central European Highlands province

- 2.33.12 Balkan Highlands province

- 2.34.12 Caucaso-Iranian Highlands (= Caucasus + Kurdistan-Iran) province

- 2.35.12 Altai Highlands province

- 2.36.12 Pamir-Tian-Shan Highlands province

- 2.37.12 Hindu Kush Highlands province

- 2.38.12 Himalayan Highlands province

- 2.39.12 Szechwan Highlands province

- 2.40.13 Macaronesian Islands province (= 4 island provinces)

- 2.41.13 Ryukyu Islands province

- 2.42.14 Lake Ladoga province

- 2.43.14 Aral Sea province

- 2.44.14 Lake Baikal province

- 3.1.1 Guinean Rain Forest province

- 3.2.1 Congo Rain Forest province

- 3.3.1 Malagasy Rain Forest province

- 3.4.4 West African Woodland/savanna province

- 3.5.4 East African Woodland/savanna province

- 3.6.4 Congo Woodland/savanna province

- 3.7.4 Miombo Woodland/savanna province

- 3.8.4 South African Woodland/savanna province

- 3.9.4 Malagasy Woodland/savanna province

- 3.10.4 Malagasy Thorn Forest province

- 3.11.6 Cape Sclerophyll province

- 3.12.7 Western Sahel province

- 3.13.7 Eastern Sahel province

- 3.14.7 Somalian province

- 3.15.7 Namib province

- 3.16.7 Kalahari province

- 3.17.7 Karroo province

- 3.18.12 Ethiopian Highlands province

- 3.19.12 Guinean Highlands province

- 3.20.12 Central African Highlands province

- 3.21.12 East African Highlands province

- 3.22.12 South African Highlands province

- 3.23.13 Ascension and St. Helena Islands province

- 3.24.13 Comores Islands and Aldabra province

- 3.25.13 Mascarene Islands province

- 3.26.14 Lake Rudolf province

- 3.27.14 Lake Ukerewe (Victoria) province

- 3.28.14 Lake Tanganyika province province

- 3.29.14 Lake Malawi (Nyasa) province

- 4.1.1 Malabar Rainforest province

- 4.2.1 Ceylonese Rainforest province

- 4.3.1 Bengalian Rainforest province

- 4.4.1 Burman Rainforest province

- 4.5.1 Indochinese Rainforest province

- 4.6.1 South Chinese Rainforest province

- 4.7.1 Malayan Rainforest province

- 4.8.4 Indus-Ganges Monsoon Forest province

- 4.9.4 Burma Monsoon Forest province

- 4.10.4 Thailandian Monsoon Forest province

- 4.11.4 Mahanadian province

- 4.12.4 Coromandel province

- 4.13.4 Ceylonese Monsoon Forest province

- 4.14.4 Deccan Thorn Forest province

- 4.15.7 Thar Desert province

- 4.16.12 Seychelles and Amirantes Islands province

- 4.17.12 Laccadives Islands province

- 4.18.12 Maldives and Chagos Islands province

- 4.19.12 Cocos-Keeling and Christmas Islands province

- 4.20.12 Andaman and Nicobar Islands province

- 4.21.12 Sumatra province

- 4.22.12 Java province

- 4.23.12 Lesser Sunda Islands province

- 4.24.12 Celebes province

- 4.25.12 Borneo province

- 4.26.12 Philippines province

- 4.27.12 Taiwan province

- 5.1.13 Papuan province

- 5.2.13 Micronesian province

- 5.3.13 Hawaiian province

- 5.4.13 Southeastern Polynesian province

- 5.5.13 Central Polynesian province

- 5.6.13 New Caledonian province

- 5.7.13 East-Melanesian province

- 6.1.1 Queensland Coastal province

- 6.2.2 Tasmanian province

- 6.3.4 Northern Coastal province

- 6.4.6 Western Sclerophyll province

- 6.5.6 Southern Sclerophyll province

- 6.6.6 Eastern Sclerophyll province≠

- 6.7.6 Brigalow province

- 6.8.7 Western Mulga province

- 6.9.7 Central Desert province

- 6.10.7 Southern Mulga/Saltbush province

- 6.11.10 Northern Savanna province

- 6.12.10 Northern Grasslands province

- 6.13.11 Eastern Grasslands and Savannas province

- 7.1.2 Neozealandia province

- 7.2.9 Maudlandia province

- 7.3.9 Marielandia province

- 7.4.9 Insulantarctica province

- 8.1.1 Campechean province (= Campeche)

- 8.2.1 Panamanian province

- 8.3.1 Colombian Coastal province

- 8.4.1. Guyanan province

- 8.5.1 Amazonian province

- 8.6.1. Madeiran province

- 8.7.1 Serra do mar province (= Bahian coast)

- 8.8.2 Brazilian Rain Forest province (= Brazilian Deciduous Forest)

- 8.9.2 Brazilian Planalto province (= Brazilian Araucaria Forest)

- 8.10.2 Valdivian Forest province (= Chilean Temperate Rain Forest, in part)

- 8.11.2 Chilean Nothofagus province (= Chilean Temperate Rain Forest, in part)

- 8.12.4 Everglades province

- 8.13.4 Sinaloan province

- 8.14.4 Guerreran province

- 8.15.4 Yucatecan province (= Yucatan)

- 8.16.4 Central American province (= Carib-Pacific)

- 8.17.4 Venezuelan Dry Forest province

- 8.18.4 Venezuelan Deciduous Forest province

- 8.19.4 Equadorian Dry Forest province

- 8.20.4 Caatinga province

- 8.21.4 Gran Chaco province

- 8.22.5 Chilean Araucaria Forest province

- 8.23.6 Chilean Sclerophyll province

- 8.24.7 Pacific Desert province (= Peruvian + Atacama Desert)

- 8.25.7 Monte (= Argentinian Thorn-scrub) province

- 8.26.8 Patagonian province

- 8.27.10 Llanos province

- 8.28.10 Campos Limpos province (= Guyana highlands)

- 8.29.10 Babacu province

- 8.30.10 Campos Cerrados province (= Campos)

- 8.31.11 Argentinian Pampas province (= Pampas)

- 8.32.11 Uruguayan Pampas province

- 8.33.12 Northern Andean province (= Northern Andes)

- 8.34.12 Colombian Montane province

- 8.35.12 Yungas province (= Andean cloud forest)

- 8.36.12 Puna province

- 8.37.12 Southern Andean province (= Southern Andes)

- 8.38.13 Bahamas-Bermudan province (= Bahamas + Bermuda)

- 8.39.13 Cuban province

- 8.40.13 Greater Aritillean province (= Jamaica + Hispaniola + Puerto Rico)

- 8.41.13 Lesser Antillean province (= Lesser Antilles)

- 8.42.13 Revilla Gigedo Island province

- 8.43.13 Cocos Island province

- 8.44.13 Galapagos Islands province

- 8.45.13 Fernando de Noronja Island province

- 8.46.13 South Trinidade Island province

- 8.47.14 Lake Titicaca province

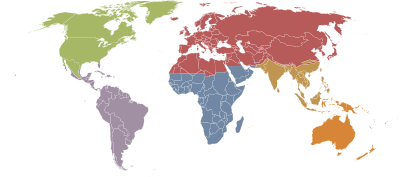

WWF / Global 200 biogeographic realms (BBC "ecozones")

The World Wildlife Fund scheme (Olson & Dinerstein, 1998, Olson et al., 2001)[7][8] is broadly similar to Miklos Udvardy's system,[1] the chief difference being the delineation of the Australasian realm relative to the Antarctic, Oceanic, and Indomalayan realms. In the WWF system, The Australasia realm includes Australia, Tasmania, the islands of Wallacea, New Guinea, the East Melanesian islands, New Caledonia, and New Zealand. Udvardy's Australian realm includes only Australia and Tasmania; he places Wallacea in the Indomalayan Realm, New Guinea, New Caledonia, and East Melanesia in the Oceanian Realm, and New Zealand in the Antarctic Realm.

| Biogeographic realm |

Area | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| million square kilometres | million square miles | ||

| Palearctic | 54.1 | 20.9 | including the bulk of Eurasia and North Africa |

| Nearctic | 22.9 | 8.8 | including most of North America |

| Afrotropic | 22.1 | 8.5 | including Trans-Saharan Africa and Arabia |

| Neotropic | 19.0 | 7.3 | including South America, Central America, and the Caribbean |

| Australasia | 7.6 | 2.9 | including Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, and neighbouring islands. The northern boundary of this zone is known as the Wallace line. |

| Indo-Malaya | 7.5 | 2.9 | including the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and southern China |

| Oceania | 1.0 | 0.39 | including Polynesia (except New Zealand), Micronesia, and the Fijian Islands |

| Antarctic | 0.3 | 0.12 | including Antarctica. |

The Palearctic and Nearctic are sometimes grouped into the Holarctic realm.

Morrone (2015) biogeographic kingdoms

Following the nomenclatural conventions set out in the International Code of Area Nomenclature, Morrone (2015) defined the next biogeographic kingdoms (or realms) and regions:[9]

- Holarctic kingdom Heilprin (1887)

- Nearctic region Sclater (1858)

- Palearctic region Sclater (1858)

- Holotropical kingdom Rapoport (1968)

- Neotropical region Sclater (1858)

- Ethiopian region Sclater (1858)

- Oriental region Wallace (1876)

- Austral kingdom Engler (1899)

- Cape region Grisebach (1872)

- Andean region Engler (1882)

- Australian region Sclater (1858)

- Antarctic region Grisebach (1872)

- Transition zones:

- Mexican transition zone (Nearctic–Neotropical transition)

- Saharo-Arabian transition zone (Palearctic–Ethiopian transition)

- Chinese transition zone (Palearctic–Oriental transition zone transition)

- Indo-Malayan, Indonesian or Wallace’s transition zone (Oriental–Australian transition)

- South American transition zone (Neotropical–Andean transition)

Freshwater biogeographic realms

The applicability of Udvardy (1975) scheme to most freshwater taxa is unresolved.[10]

The drainage basins of the principal oceans and seas of the world are marked by continental divides. The grey areas are endorheic basins that do not drain to the ocean.

Marine biogeographic realms

According to Briggs (1995):[11][12]

- Indo-West Pacific region

- Eastern Pacific region

- Western Atlantic region

- Eastern Atlantic region

- Southern Australian region

- Northern New Zealand region

- Western South America region

- Eastern South America region

- Southern Africa region

- Mediterranean–Atlantic region

- Carolina region

- California region

- Japan region

- Tasmanian region

- Southern New Zealand region

- Antipodean region

- Subantarctic region

- Magellan region

- Eastern Pacific Boreal region

- Western Atlantic Boreal region

- Eastern Atlantic Boreal region

- Antarctic region

- Arctic region

According to the WWF scheme (Spalding, 2007):[13]

- Arctic realm

- Temperate Northern Atlantic realm

- Temperate Northern Pacific realm

- Tropical Atlantic realm

- Western Indo-Pacific realm

- Central Indo-Pacific realm

- Eastern Indo-Pacific realm

- Tropical Eastern Pacific realm

- Temperate South America realm

- Temperate Southern Africa realm

- Temperate Australasia realm

- Southern Ocean realm

See also: Longhurst provinces

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Udvardy, M. D. F. (1975). A classification of the biogeographical provinces of the world. IUCN Occasional Paper no. 18. Morges, Switzerland: IUCN, .

- ↑ Wicken, E. B. 1986. Terrestrial ecozones of Canada / Écozones terrestres du Canada. Environment Canada. Ecological Land Classification Series No. 19. Lands Directorate, Ottawa. 26 pp., .

- ↑ Scott, G. 1995. Canada's vegetation: a world perspective, p., .

- ↑ Schültz, J. Die Ökozonen der Erde, 1st ed., Ulmer, Stuttgart, Germany, 1988, 488 pp.; 2nd ed., 1995, 535 pp.; 3rd ed., 2002. Transl.: The Ecozones of the World: The Ecological Divisions of the Geosphere. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1995; 2nd ed., 2005, .

- ↑ Olson, D. M. & E. Dinerstein (1998). The Global 200: A representation approach to conserving the Earth’s most biologically valuable ecoregions. Conservation Biol. 12:502–515, .

- ↑ BBC Nature - Ecozones.

- ↑ Olson, D. M. & E. Dinerstein (1998). The Global 200: A representation approach to conserving the Earth’s most biologically valuable ecoregions. Conservation Biol. 12:502–515, .

- ↑ Olson, D. M., Dinerstein, E., Wikramanayake, E. D., Burgess, N. D., Powell, G. V. N., Underwood, E. C., D'Amico, J. A., Itoua, I., Strand, H. E., Morrison, J. C., Loucks, C. J., Allnutt, T. F., Ricketts, T. H., Kura, Y., Lamoreux, J. F., Wettengel, W. W., Hedao, P., Kassem, K. R. (2001). Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. Bioscience 51(11):933-938, .

- ↑ Morrone, J. J. (2015). Biogeographical regionalisation of the world: a reappraisal. Australian Systematic Botany 28: 81-90, .

- ↑ Abell, R., M. Thieme, C. Revenga, M. Bryer, M. Kottelat, N. Bogutskaya, B. Coad, N. Mandrak, S. Contreras-Balderas, W. Bussing, M. L. J. Stiassny, P. Skelton, G. R. Allen, P. Unmack, A. Naseka, R. Ng, N. Sindorf, J. Robertson, E. Armijo, J. Higgins, T. J. Heibel, E. Wikramanayake, D. Olson, H. L. Lopez, R. E. d. Reis, J. G. Lundberg, M. H. Sabaj Perez, and P. Petry. (2008). Freshwater ecoregions of the world: A new map of biogeographic units for freshwater biodiversity conservation. BioScience 58:403-414, .

- ↑ Briggs, J.C. (1995). Global Biogeography. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- ↑ Morrone, J. J. (2009). Evolutionary biogeography, an integrative approach with case studies. Columbia University Press, New York, .

- ↑ Spalding, M. D. et al. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the world: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. BioScience 57: 573-583, .

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ecozones. |