Bilbao (Mesoamerican site)

Bilbao is a Mesoamerican archaeological site about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the modern town of Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa in the Escuintla department of Guatemala.[2] The site lies among sugar plantations on the Pacific coastal plain and its principal phase of occupation is dated to the Classic Period.[3] Bilbao was a major centre belonging to the Cotzumalhuapa culture with its main occupation dating to the Late Classic (c. AD 600–800).[4] Bilbao is the former name of the plantation on which the site lies and from which it has derived its name.[5]

Location

Bilbao lies of the outskirts of Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa, situated approximately 370 metres (1,210 ft) above mean sea level.[6] The archaeological sites of Bilbao, El Baúl and El Castillo were all parts of the same urban centre that extended over about 10 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi). This extended urban area is known as the Cotzumalhuapa Nuclear Zone by archaeologists and Bilbao lies in the southernmost part of this area. The urban growth of modern Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa has expanded to the edge of the monumental architecture of the site.[7]

The dominant geographical feature close to the Cotzumalhaupa Nuclear Zone is the Volcán de Fuego, one of the most active volcanoes in the world, its crater rising to an altitude of 3,835 metres (12,582 ft) above mean sea level at only a distance of about 21 kilometres (13 mi) from Bilbao itself. The activity of the volcano must have impacted upon the population of the site, which must regularly have suffered from falls of volcanic ash, affecting agriculture, transport routes and perishable dwellings.[8]

History

Preclassic Period

Bilbao was occupied since the Preclassic and was the most important site dating to the Preclassic within what became in later periods the Cotzumalhuapa Nuclear Zone.[7]

Classic Period

A substantial quantity of Middle Classic and Late Classic ceramics were found in mixed deposits at Bilbao.[7]

Postclassic Period

Although Postclassic remains are found close to the surface in various parts of the Cotzumalhuapa Nuclear Zone, Bilbao has a residential compound that is the only major structure dating to this period within the Zone.[7]

Modern history

The land containing the archaeological remains was cleared in 1860 by Pedro de Anda, a local civic official, to establish a coffee plantation by the name of Finca Peor es Nada. In 1890 Finca Bilbao was formed from the merging of Finca Peor es Nada with another plot of land. The plantation was renamed to Finca Las Ilusiones in 1957.[9]

Austrian physician Simeon Habel drew some of the sculptures at Bilbao in 1863, his drawings were published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1878. Adolph Bastian of the Royal Museum in Berlin visited the site in 1876 and entered into a contract with Pedro de Anda to explore the remains. At this time Carl H. Berendt was hired to move the finest monuments to the Royal Museum in 1877. The monuments were shipped from Puerto San José on the Pacific coast, where one of the monuments was lost overboard. The rest arrived in Berlin in 1883 and totalled 31 in all, including some well-preserved stelae depicting ballplayers.[10] In 1884 engineer Albert Napp mapped the site, his original map being lost for more than a century before being found in 1994 in Berlin.[11]

The site

The architectural remains consist of earth mounds covered by sugarcane plantations.[5] The sculptural style of the site differs from that of the Classic Maya and may represent the vanguard of the Nahua-speaking Pipil who migrated from central Mexico and settled the Pacific coastal plain of Guatemala and El Salvador in the Postclassic Period.[12] The Mexican influence evident at Bilbao may not have arrived directly but could instead have been transmitted via a neighbouring polity such as groups from the Tiquisate or La Gomera areas of the Guatemalan Pacific coastal region.[13]

When first discovered the site was covered in forest, this was cleared for coffee plantations that have since been replaced with sugarcane.[14]

Archaeological investigations were carried out by Lee A. Parsons and S. F. de Borhegyi. Parsons has suggested that Bilbao was a colony founded during the Middle Classic (c. 400–550) by the distant metropolis of Teotihuacan in the Valley of Mexico, with El Tajín as an intermediary, and that it became independent between AD 550 and 700.[15] However, archaeologist Marion Popenoe de Hatch has since redated the site to the Late Classic period.[16] Bilbao's architecture is buried under a thick layer of volcanic soil to an extent that only the largest structures can be distinguished as mounds.[17]

The core of Bilbao is formed by a series of platforms that descend gradually to the south. These platforms do not have any surviving evidence of boundary walls and appear to have been open and accessible. The monumental architecture of Bilbao may have served as an elite residential compound and a place of worship.[18]

The Monument Plaza contained the majority of the site's sculpture, including Monuments 1 through to 8, a group of stelae now in Berlin.[19] The Plaza was externally accessible via ramps and stairways.[20]

Group A lies immediately to the west of the Monument Plaza and contains 6 structures.[21]

Group B is immediately to the north of Group A and contains 4 structures.[21]

Group C is immediately north of Group B and possesses 3 structures.[21]

Group D is immediately north of Group C and contains 4 structures.[21]

Groups A to D are all bordered on the east side by the Canilla River.[21]

Causeways

Bilbao is connected to other sites in the Cotzumalhuapa Nuclear Zone by a system of stone-paved avenues, reinforcing the interpretation of the Zone as an articulated urban centre. There are three major causeways:[7]

The Gavarrete Causeway is 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) long and links Bilbao with El Baúl.[7] It was the main avenue of the city and varied between 11 and 14 metres (36 and 46 ft) wide. The causeway is named after Guatemalan historian Juan Gavarrete.[22]

The Berendt Causeway is an extension of the Gavarrete Causeway that links Bilbao with El Castillo, it is 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) long.[7]

The Habel Causeway is 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) long and links El Castillo with Golón, only 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from Bilbao itself.[7]

Sculpture

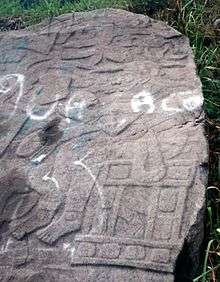

58 monuments were listed by Parsons at Bilbao,[1] but only 3 remain in situ in Bilbao's Monument Plaza.[14] Even before the extraction of the majority of the sculptures in the 19th century, many had already been damaged by locals who quarried them as a source of construction material.[24] The remaining boulder sculptures of Bilbao lie among the earth mounds of the site's ceremonial centre; they include two sculptures of the central Mexican deity Tlaloc carved into a boulder by a stream.[16] A significant amount of the architecture and relief sculpture at the site features ballgame imagery.[25] Ballgame reliefs at Bilbao feature blossoming and fruiting plants symbolic of agricultural fertility.[26] Stelae at Bilbao depict ballplayers with disembodied heads and various sculptures depict dismembered body parts.[27] Sculptures of dismembered limbs are carved in the round and show the bones protruding.[28]

Well-preserved examples of Late Preclassic potbelly sculptures have been found at Bilbao. These are boulders carved to represent obese human figures and are found at many sites along the Pacific coast.[29]

Monument 1 dates to the Classic Period. It depicts a ballplayer wielding a knife in one hand and a severed head in the other. This figure stands on a dismembered human torso lacking limbs and head. Around the main figure are four smaller figures, also carrying severed heads.[30] It was originally found in the Monument Plaza but was removed to the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.[31]

Monument 2 was located in the Monument Plaza and was removed to the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.[31]

Monument 3 depicts a larger ballplayer figure and a smaller death god, both of whom are wearing ballgame yokes, standing in front of a temple. The ballplayer is offering a human heart to the sun.[32] The monument was found in the Monument Plaza but was removed to the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.[31]

Monument 4 depicts a shaman whose tongue is in the form of a knife.[33] It was located in the Monument Plaza and was removed to the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.[31]

Monument 5, Monument 6, Monument 7 and Monument 8 were all from the Monument Plaza and were removed to the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.[31]

Monument 16 is one of the few sculptures to remain at the site, being located in a sugarcan field.[7]

Monument 17 was lost overboard when it was being loaded onto a ship for transport to Berlin. The sculpture was one of a pair and depicted a vulture devouring a human torso. Only the tip of one wing survived and is stored in the museum warehouse.[11]

Monument 18 is a large sculptured stela that is roughly rectangular in shape and has a raised border. It depicts three standing figures. The left-most figure faces the other two on its right. Between the left figure and the central figure is a rectangular object sprouting crab claws at the bottom. There is a circle containing the head of a monkey at the top of the sculpture. Monument 18 has been dated to the Classic period.[5] Monument 18 was located on the west side of Mound 4 of Group B.[34]

Monument 19 depicts three figures, the principal individual wears an elaborate headdress with a Xiuhcoatl ("turquoise/fire serpent") plume. He appears to be offering aid to a less fortunate person.[35]

Monument 21 is a basalt boulder in a sugarcane field. The boulder has an artificially flattened upper surface bearing a bas-relief sculpture. The carved face has a 35° slope and measures 11 by 13 feet (3.4 by 4.0 m). The sculpture depicts three main figures. The central figure is the largest and faces towards a second figure seated on a throne. The third figure is behind the central figure, it is smaller and holds a hand puppet. The scene is filled out with twisting vines that sprout cocoa pods bearing human faces. Other details of the monument include birds, snakes and a butterfly with a human head. Monument 21 has been dated to the Classic period.[5] Monument 21 is located east of Mound 2, in the centre of Group B.[36] The decoration on the skirt of one of the figures may be the face of the central Mexican deity Xipe Totec.[13]

Monument 24 was moved to the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City.[14]

Monument 46 is a potbelly sculpture.[37]

Monument 47 is a potbelly sculpture.[37]

Monument 58 is a potbelly sculpture. When it was excavated by Parsons it was found lying on its side with its head resting upon the lowest step of a stairway with Monument 59 (a throne or altar) upside down on top of it. The potbelly sculpture may originally have sat upon the throne. Alternatively, it may have been set at the base of the stairway with the throne at the top.[38]

Monument 59 is a stone altar or throne with four legs. It was found resting inverted on top of Monument 58, a potbelly sculpture, at the bottom of a stairway. It may originally have supported this potbelly monument.[39]

Golón

Golón is an important area within the Cotzumalhuapa Nuclear Zone, located 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from Bilbao and connected to the same system of paved causeways. Golón is an area that contains further monumental sculpture.[7]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Kelly 1996, p.220.

- ↑ Adams 1996, p.227. Kelly 1996, p.219.

- ↑ Sharer 2000, pp.482-3. Adams 1996, p.228.

- ↑ Sharer 2000, pp.482-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Kelly 1996, p.217.

- ↑ Benítez et al 1993, p.208.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Chinchilla 2001.

- ↑ Chinchilla Mazariegos 2006, p.119-120.

- ↑ Kelly 1996, pp.220-221.

- ↑ Kelly 1996, p.221.

- 1 2 Chinchilla Mazariegos 1997, p.216.

- ↑ Sharer 2000, pp.483-4.

- 1 2 Rubio 1994, p.91.

- 1 2 3 Chinchilla Mazariegos 1997, p.214.

- ↑ Adams 1996, p.227.

- 1 2 Adams 1996, p.228.

- ↑ Chinchilla 2002, p.430.

- ↑ Chinchilla Mazariegos 1998, p.514. Chinchilla Mazariegos 2003.

- ↑ Chinchilla Mazariegos 1997, pp.214-215.

- ↑ Chinchilla Mazariegos 1998, p.514.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chinchilla Mazariegos 1997, p.222.

- ↑ Chinchilla 2003.

- ↑ Rubio 1994, p.89.

- ↑ Chinchilla Mazariegos 1997, p.215.

- ↑ Cohodas 1991, p.282.

- ↑ Gillespie 1991, p.319.

- ↑ Gillespie 1991, pp.322, 334.

- ↑ Parsons 1991, p.204.

- ↑ Sharer & Traxler 2006, p.245.

- ↑ Gillespie 1991, pp.334-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chinchilla Mazariegos 1997, pp.214-216.

- ↑ Rubio 1994, p.93. Miller 2001, p.101.

- ↑ Rubio 1994, p.95.

- ↑ Chinchilla Mazariegos 1997, pp.222, 224.

- ↑ Rubio 1994, pp.88-89.

- ↑ Rubio 1994, p.88.

- 1 2 McInnis Thompson & Valdez 2008, p.25.

- ↑ McInnis Thompson & Valdez 2008, pp.13, 24.

- ↑ p.24.

References

- Adams, Richard E.W. (1996). Prehistoric Mesoamerica (Revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2834-8. OCLC 22593466.

- Benítez, José; Teresita Chinchilla; Eugenia J. Robinson (1993). "La Estela 1 de Santa Rosa, departamento de Sacatepéquez" (versión digital). III Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1989 (edited by J.P. Laporte, H. Escobedo and S. Villagrán) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 206–213. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo (1997). "Las esculturas de Cotzumalguapa en el Museo Etnográfico de Berlin" (versión digital). X Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1996 (edited by J.P. Laporte and H. Escobedo) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 214–226. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo (1998). "El Baúl: Un sitio defensivo en la zona nuclear de Cotzumalguapa" (versión digital). XI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1997 (edited by J.P. Laporte and H. Escobedo) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 512–522. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Chinchilla, Oswaldo (2001). "Archaeological Research at Cotzumalhuapa, Guatemala" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI). Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Chinchilla, Oswaldo (2002). "Investigaciones por medio de radar de penetración al suelo (GPR) en la zona nuclear de Cotzumalguapa, Escuintla" (versión digital). XV Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2001 (edited by J.P. Laporte, H. Escobedo y B. Arroyo) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 430–445. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo (2003). "Analysis of Archaeological Artifacts from Cotzumalhuapa, Guatemala". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI). Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo; Elisa Mencos; Jorge Cárcamo; José Vicente Genovez (2006). "Paisaje y asentamientos en Cotzumalguapa" (versión digital). XIX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2005 (edited by J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo and H. Mejía) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 116–130. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Cohodas, Marvin (1991). "Ballgame Imagery of the Maya Lowlands: History and Iconography". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox. The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 251–288. ISBN 0-8165-1360-0. OCLC 51873028.

- Gillespie, Susan D. (1991). "Ballgames and Boundaries". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox. The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 317–345. ISBN 0-8165-1360-0. OCLC 51873028.

- Kelly, Joyce (1996). An Archaeological Guide to Northern Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2858-5. OCLC 34658843.

- McInnis Thopmson, Lauri; Fred Valdez Jr. (2008). "Potbelly Sculpture: An Inventory and Analysis". Ancient Mesoamerica. USA: Cambridge University Press. 19 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1017/S0956536108000278.

- Miller, Mary Ellen (2001). The Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec. World of Art series (3rd ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20345-8. OCLC 59530512.

- Parsons, Lee A. (1991). "The Ballgame in the Southern Pacific Coast Cotzumalhuapa Region and Its Impact on Kaminaljuyu During the Middle Classic". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox. The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 195–212. ISBN 0-8165-1360-0. OCLC 51873028.

- Rubio, Rolando Roberto (1994). "Evidencia cerámica y su relación con los gobernantes de Cotzumalguapa durante el periodo Clásico Tardío" (versión digital). I Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1987 (edited by J.P. Laporte, H. Escobedo y S. Villagrán) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 85–97. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Sharer, Robert J. (2000). "The Maya Highlands and the Adjacent Pacific Coast". In Richard E.W. Adams; Murdo J. Macleod. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 449–499. ISBN 0-521-35165-0. OCLC 33359444.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

Coordinates: 14°20′59″N 91°01′40″W / 14.3497°N 91.0278°W