Symmetry in biology

Symmetry in biology is the balanced distribution of duplicate body parts or shapes within the body of an organism. In nature and biology, symmetry is always approximate: for example plant leaves, while considered symmetrical, rarely match up exactly when folded in half. Symmetry creates a class of patterns in nature, where the near-repetition of the pattern element is by reflection or rotation. The body plans of most multicellular organisms exhibit some form of symmetry, whether radial, bilateral, or spherical. A small minority, notably among the sponges, exhibit no symmetry (i.e., are asymmetric).

Radial symmetry

Radially symmetric organisms resemble a pie where several cutting planes produce roughly identical pieces. Such an organism exhibits no left or right sides. They have a top and a bottom surface, or a front and a back.

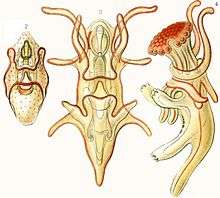

Symmetry has been important historically in the taxonomy of animals; animals with radial symmetry were classified in the taxon Radiata, which is now generally accepted to be a polyphyletic assemblage of different phyla of the Animal kingdom. Most radially symmetric animals are symmetrical about an axis extending from the center of the oral surface, which contains the mouth, to the center of the opposite, or aboral, end. Radial symmetry is especially suitable for sessile animals such as the sea anemone, floating animals such as jellyfish, and slow moving organisms such as starfish. Animals in the phyla cnidaria and echinodermata are radially symmetric,[1] although many sea anemones and some corals have bilateral symmetry defined by a single structure, the siphonoglyph.[2]

Many flowers are radially symmetric or actinomorphic. Roughly identical flower parts – petals, sepals, and stamens occur at regular intervals around the axis of the flower, which is often the female part, with the carpel, style and stigma.[3]

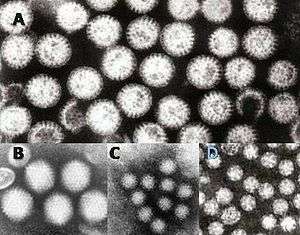

Many viruses have radial symmetries, their coats being composed of a relatively small number of protein molecules arranged in a regular pattern to form polyhedrons, spheres, or ovoids. Most are icosahedrons.[4]

Special forms of radial symmetry

Tetramerism is a variant of radial symmetry found in jellyfish, which have four canals in an otherwise radial body plan.

Pentamerism, another variant of radial symmetry (also called pentaradial and pentagonal symmetry), means the organism is in five parts around a central axis, 72° apart. Among animals, only the echinoderms such as sea stars, sea urchins, and sea lilies are pentamerous as adults, with five arms arranged around the mouth. Being bilaterian animals, however, they initially develop with mirror symmetry as larvae, then gain pentaradial symmetry later.[5]

Flowering plants show fivefold symmetry in many flowers and in various fruits. This is well seen in the arrangement of the five carpels (the botanical fruits containing the seeds) in an apple cut transversely.

Hexamerism is found in the corals and sea anemones (class Anthozoa) which are divided into two groups based on their symmetry. The most common corals in the subclass Hexacorallia have a hexameric body plan; their polyps have sixfold internal symmetry and the number of their tentacles is a multiple of six.

Octamerism is found in corals of the subclass Octocorallia. These have polyps with eight tentacles and octameric radial symmetry. The octopus, however, has bilateral symmetry, despite its eight arms.

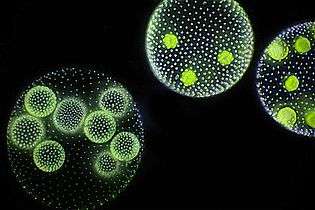

Spherical symmetry

Spherical symmetry occurs in an organism if it is able to be cut into two identical halves through any cut that runs through the organism's center. Organisms which show approximate spherical symmetry include the freshwater green alga Volvox.[1]

Bilateral symmetry

In bilateral symmetry (also called plane symmetry), only one plane, called the sagittal plane, divides an organism into roughly mirror image halves. Thus there is approximate reflection symmetry. Internal organs are however not necessarily symmetric.

Animals that are bilaterally symmetric have mirror symmetry in the sagittal plane, which divides the body vertically into left and right halves, with one of each sense organ and limb pair on either side. The great majority (at least 99%) of animals are bilaterally symmetric, including humans (see also facial symmetry).[6][7][8] Humans find bilaterally symmetrical faces more attractive than those which are not; this may be a cue that such people are healthier and genetically fitter when selecting a mate.[9]

When an organism normally moves in one direction, it inevitably has a front or head end. This end encounters the environment before the rest of the body as the organism moves along, so sensory organs such as eyes tend to be clustered there, and similarly it is the likely site for a mouth as food is encountered.[8] A distinct head, with sense organs connected to a central nervous system, therefore (on this view) tends to develop (cephalization). Given a direction of travel which creates a front/back difference, and gravity which creates a dorsal/ventral difference, left and right are unavoidably distinguished, so a bilaterally symmetric body plan is widespread and found in most animal phyla.[8][10] Bilateral symmetry also permits streamlining to reduce drag, and on a traditional view in zoology facilitates locomotion.[8] However, in the Cnidaria, different symmetries exist, and bilateral symmetry is not necessarily aligned with the direction of locomotion, so another mechanism such as internal transport may be needed to explain the origin of bilateral symmetry in animals.[8][11]

The phylum Echinodermata, which includes starfish, sea urchins and sand dollars, is unique among animals in having bilateral symmetry at the larval stage, but fivefold symmetry (pentamerism, a special type of radial symmetry) as adults.[12]

Bilateral symmetry is not easily broken. In experiments using the fruit fly, Drosophila, in contrast to other traits (where laboratory selection experiments always yield a change), right or left-sidedness in eye size, or eye facet number, wing-folding behavior (left over right) show a lack of response.[13]

Females of some species select for symmetry, presumed by biologists to be a mark (technically a "cue") of fitness. Female barn swallows, a species where adults have long tail streamers, prefer to mate with males that have the most symmetrical tails.[14]

.jpg)

Flowers in some families of flowering plants, such as the orchid and pea families, and also most of the figwort family,[15] are bilaterally symmetric (zygomorphic).[16]

Biradial symmetry

Biradial symmetry is a combination of radial and bilateral symmetry, as in the Ctenophores. Here, the body components are arranged with similar parts on either side of a central axis, and each of the four sides of the body is identical to the opposite side but different from the adjacent side. This may represent a stage in the evolution of bilateral symmetry "from a presumably radially symmetrical ancestor."[11]

Asymmetry

Not all animals are symmetric. Many members of the phylum Porifera (sponges) have no symmetry (while others are radially symmetric).[17]

It is normal for essentially symmetric animals to show some measure of asymmetry. Usually in humans the left brain is structured differently to the right, the heart is positioned towards the left, and the right hand functions better than the left hand.[18] The scale-eating cichlid Perissodus microlepis develops left or right asymmetries in their mouths and jaws that allow them to be more effective when removing scales from the left or right flank of their prey.[19] The approximately 400 species of flatfish also lack symmetry as adults, though the larvae are bilaterally symmetrical. Adult flatfish rest on one side, and the eye that was on that side has migrated round to the other (top) side of the body.[20]

References

- 1 2 Chandra, Girish. "Symmetry". IAS. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ Finnerty JR (2003). "The origins of axial patterning in the metazoa: How old is bilateral symmetry?". The International journal of developmental biology. 47 (7–8): 523–9. PMID 14756328. 14756328 16341006.

- ↑ Endress, P.K. (February 2001). "Evolution of Floral Symmetry". Current Opinion Plant Biology. 4 (1): 86–91. PMID 11163173. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00140-0.

- ↑ Horne, R. W.; Wildy, P. (1961). "Symmetry in virus architecture". Virology. 15 (3): 348–373. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(61)90366-X.

- ↑ Stewart, 2001. pp 64-65.

- ↑ Valentine, James W. "Bilateria". AccessScience. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Bilateral symmetry". Natural History Museum. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Finnerty, John R. (2005). "Did internal transport, rather than directed locomotion, favor the evolution of bilateral symmetry in animals?" (PDF). BioEssays. 27: 1174–1180. PMID 16237677. doi:10.1002/bies.20299.

- ↑ "Bilateral Symmetry". biologydictionary.net. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "Bilateral (left/right) symmetry". Berkeley. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- 1 2 Martindale, Mark Q.; Henry, Jonathan Q. (1998). "The Development of Radial and Biradial Symmetry: The Evolution of Bilaterality1" (PDF). American Zoology. 38 (4): 672–684. doi:10.1093/icb/38.4.672.

- ↑ Fox, Richard. "Asterias forbesi". Invertebrate Anatomy OnLine. Lander University. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ Symmetry breaking in fruit flies

- ↑ Maynard Smith, John; Harper, David (2003). Animal Signals. Oxford University Press. pp. 63-65.

- ↑ "SCROPHULARIACEAE - Figwort or Snapdragon Family". Texas A&M University Bioinformatics Working Group. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ Symmetry, biological, from The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (2007).

- ↑ Myers, Phil (2001). "Porifera Sponges". University of Michigan (Animal Diversity Web). Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ Lopsided fish show that symmetry is only skin deep BioMed Central, 22 January 2010.

- ↑ Lee HJ, Kusche H, Meyer A (2012). "Handed Foraging Behavior in Scale-Eating Cichlid Fish: Its Potential Role in Shaping Morphological Asymmetry". PLoS ONE. 7 (9): e44670. PMC 3435272

. PMID 22970282. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044670.

. PMID 22970282. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044670. - ↑ Friedman, Matt (2008). "The evolutionary origin of flatfish asymmetry". Nature. 454 (7201): 209–212. PMID 18615083. doi:10.1038/nature07108.

Sources

- Ball, Philip (2009). Shapes. Oxford University Press.

- Stewart, Ian (2007). What Shape is a Snowflake? Magical Numbers in Nature. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Thompson, D'Arcy (1942). On Growth and Form. Cambridge University Press.

.jpg)