Eschatology

| Part of a series on |

| Eschatology |

|---|

|

|

Eschatology /ˌɛskəˈtɒlədʒi/ is a part of theology concerned with the final events of history, or the ultimate destiny of humanity. This concept is commonly referred to as the "end of the world" or "end time."

The word arises from the Greek ἔσχατος eschatos meaning "last" and -logy meaning "the study of", first used in English around 1844.[1] The Oxford English Dictionary defines eschatology as "The part of theology concerned with death, judgment, and the final destiny of the soul and of humankind."[2]

In the context of mysticism, the phrase refers metaphorically to the end of ordinary reality and reunion with the Divine. In many religions it is taught as an existing future event prophesied in sacred texts or folklore. More broadly, eschatology may encompass related concepts such as the Messiah or Messianic Age, the end time, and the end of days.

History is often divided into "ages" (aeons), which are time periods each with certain commonalities. One age comes to an end and a new age or world to come, where different realities are present, begins. When such transitions from one age to another are the subject of eschatological discussion, the phrase, "end of the world", is replaced by "end of the age", "end of an era", or "end of life as we know it". Much apocalyptic fiction does not deal with the "end of time" but rather with the end of a certain period of time, the end of life as it is now, and the beginning of a new period of time. It is usually a crisis that brings an end to current reality and ushers in a new way of living, thinking, or being. This crisis may take the form of the intervention of a deity in history, a war, a change in the environment, or the reaching of a new level of consciousness.

Most modern eschatology and apocalypticism, both religious and secular, involve the violent disruption or destruction of the world; whereas Christian and Jewish eschatologies view the end times as the consummation or perfection of God's creation of the world. For example, according to some ancient Hebrew worldviews, reality unfolds along a linear path (or rather, a spiral path, with cyclical components that nonetheless have a linear trajectory); the world began with God and is ultimately headed toward God’s final goal for creation, the world to come.

Eschatologies vary as to their degree of optimism or pessimism about the future. In some eschatologies, conditions are better for some and worse for others, e.g. "heaven and hell".

Eschatology in religions

Bahá'í

In Bahá'í belief, creation has neither a beginning nor an end.[3] Instead, the eschatology of other religions is viewed as symbolic. In Bahá'í belief, human time is marked by a series of progressive revelations in which successive messengers or prophets come from God.[4] The coming of each of these messengers is seen as the day of judgment to the adherents of the previous religion, who may choose to accept the new messenger and enter the "heaven" of belief, or denounce the new messenger and enter the "hell" of denial. In this view, the terms "heaven" and "hell" are seen as symbolic terms for the person's spiritual progress and their nearness to or distance from God.[4] In Bahá'í belief, the coming of Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, signals the fulfilment of previous eschatological expectations of Islam, Christianity and other major religions.[5]

Buddhism

Christianity

| Christian eschatology |

|---|

| Eschatology views |

|

Contrasting beliefs |

|

Biblical texts

|

|

Key terms

|

| Christianity portal |

Christian eschatology is concerned with death, an intermediate state, Heaven, hell, the return of Jesus, and the resurrection of the dead. Several evangelical denominations include a rapture, a great tribulation, the Millennium, end of the world, the last judgment, a new heaven and a new earth (the World to Come), and the ultimate consummation of all of God's purposes. Eschatological passages are found in many places, esp. Isaiah, Daniel, Ezekiel, Matthew 24, Mark 13, The Sheep and the Goats, and the Book of Revelation, but Revelation often occupies a central place in Christian eschatology.

The Second Coming of Christ is the central event in Christian eschatology. Most Christians believe that death and suffering will continue to exist until Christ's return. There are, however, various views concerning the order and significance of other eschatological events.

The Book of Revelation is at the core of Christian eschatology. The study of Revelation is usually divided into four interpretative methodologies or hermeneutics. In the Futurist approach, Revelation is treated mostly as unfulfilled prophecy taking place in some yet undetermined future. This is the approach which most applies to eschatological studies. In the Preterist approach, Revelation is chiefly interpreted as having prophetic fulfillment in the past, principally, the events of the first century CE, such as the struggle of Christianity to survive the persecutions of the Roman Empire, the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, and the desecration of the Temple in the same year. In the Historicist approach, Revelation provides a broad view of history, and passages in Revelation are identified with major historical people and events. In the Idealist (or Spiritualist or Symbolic) approach, the events of Revelation are neither past nor future, but are purely symbolic, dealing with the ongoing struggle and ultimate triumph of good over evil.

Hinduism

Contemporary Hindu eschatology is linked in the Vaishnavite tradition to the figure of Kalki, the tenth and last avatar of Vishnu before the age draws to a close who will reincarnate as Shiva simultaneously dissolves and regenerates the universe.

Most Hindus believe that the current period is the Kali Yuga, the last of four Yuga that make up the current age. Each period has seen successive degeneration in the moral order, to the point that in the Kali Yuga quarrel and hypocrisy are the norm. In Hinduism, time is cyclic, consisting of cycles or "kalpas". Each kalpa lasts 4.1 – 8.2 billion years, which is a period of one full day and night for Brahma, who in turn will live for 311 trillion, 40 billion years. The cycle of birth, growth, decay, and renewal at the individual level finds its echo in the cosmic order, yet is affected by vagaries of divine intervention in Vaishnavite belief. Some Shaivites hold the view that Shiva is incessantly destroying and creating the world.

After this larger cycle, all of creation will contract to a singularity and then again will expand from that single point, as the ages continue in a religious fractal pattern.[6]

Islam

Islamic eschatology is documented in the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, regarding the Signs of the Day of Judgement. The Prophet's sayings on the subject have been traditionally divided into Major and Minor Signs. He spoke about several Minor Signs of the approach of the Day of Judgment, including:

- Abu Hurairah reported that Muhammad said: "If you survive for a time you would certainly see people who would have whips in their hands like the tail of an ox. They would get up in the morning under the wrath of God and they would go into the evening with the anger of God."

- Abu Hurairah narrated that Muhammad said, "When honesty is lost, then wait for the Day of Judgment." It was asked, "How will honesty be lost, O Messenger of God?" He said, "When authority is given to those who do not deserve it, then wait for the Day of Judgment."

- 'Umar ibn al-Khattāb, in a long narration, relating to the questions of the angel Gabriel, reported: "Inform me when the Day of Judgment will be." He [the Prophet Muhammad] remarked: "The one who is being asked knows no more than the inquirer." He [the inquirer] said: "Tell me about its indications." He [the Prophet Muhammad] said: "That the slave-girl gives birth to her mistress and master, and that you would find barefooted, destitute shepherds of goats vying with one another in the construction of magnificent buildings."

- "Before the Day of Judgment there will be great liars, so beware of them."

- "When the most wicked member of a tribe becomes its ruler, and the most worthless member of a community becomes its leader, and a man is respected through fear of the evil he may do, and leadership is given to people who are unworthy of it, expect the Day of Judgment."

Regarding the Major Signs, a Companion of the Prophet narrated: "Once we were sitting together and talking amongst ourselves when the Prophet appeared. He asked us what it was we were discussing. We said it was the Day of Judgment. He said: 'It will not be called until ten signs have appeared: Smoke, Dajjal (the Antichrist), the creature (that will wound the people), the rising of the sun in the West, the Second Coming of Jesus, the emergence of Gog and Magog, and three sinkings (or cavings in of the earth): one in the East, another in the West and a third in the Arabian Peninsula.'" (note: the previous events were not listed in the chronological order of appearance)

Judaism

Jewish eschatology is concerned with events that will happen in the end of days, according to the Hebrew Bible and Jewish thought. This includes the ingathering of the exiled diaspora, the coming of Jewish Messiah, afterlife, and the revival of the dead Tsadikim.

In Judaism, end times are usually called the "end of days" (aḥarit ha-yamim, אחרית הימים), a phrase that appears several times in the Tanakh. The idea of a messianic age has a prominent place in Jewish thought, and is incorporated as part of the end of days.

Judaism addresses the end times in the Book of Daniel and numerous other prophetic passages in the Hebrew scriptures, and also in the Talmud, particularly Tractate Avodah Zarah.

Zoroastrianism

Frashokereti is the Zoroastrian doctrine of a final renovation of the universe, when evil will be destroyed, and everything else will be then in perfect unity with God (Ahura Mazda). The doctrinal premises are (1) good will eventually prevail over evil; (2) creation was initially perfectly good, but was subsequently corrupted by evil; (3) the world will ultimately be restored to the perfection it had at the time of creation; (4) the "salvation for the individual depended on the sum of [that person's] thoughts, words and deeds, and there could be no intervention, whether compassionate or capricious, by any divine being to alter this." Thus, each human bears the responsibility for the fate of his own soul, and simultaneously shares in the responsibility for the fate of the world.[7]

Eschatology equivalents in science and philosophy

Futures studies and transhumanism

Researchers in futures studies and transhumanists investigate how the accelerating rate of scientific progress may lead to a "technological singularity" in the future that would profoundly and unpredictably change the course of human history, and result in Homo sapiens no longer being the dominant life form on Earth.[8][9]

Astronomy

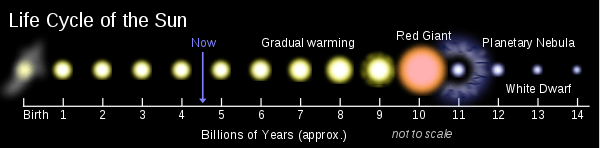

Occasionally the term "physical eschatology" is applied to the long-term predictions of astrophysics.[10][11] The Sun will turn into a red giant in approximately 6 billion years. Life on Earth will become impossible due to a rise in temperature long before the planet is actually swallowed up by the Sun.[12] Even later, the Sun will go white dwarf.

See also

References

- ↑ Dictionary – Definition of Eschatology Webster's Online Dictionary

- ↑ "Eschatology, n.", def. a, Oxford English Dictionary, accessed 2016-05-18.

- ↑ Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-521-86251-5.

- 1 2 Smith, Peter (2000). "Eschatology". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 133–134. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ↑ Buck, Christopher (2004). "The eschatology of Globalization: The multiple-messiahship of Bahā'u'llāh revisited". In Sharon, Moshe. Studies in Modern Religions, Religious Movements and the Bābī-Bahā'ī Faiths. Boston: Brill. pp. 143–178. ISBN 90-04-13904-4.

- ↑ Hooper, Rev. Richard (April 20, 2011). End of Days: Predictions of the End From Ancient Sources. Sedona, AZ. p. 156.

- ↑ Boyce, Mary (1979), Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 27–29, ISBN 978-0-415-23902-8.

- ↑ Sandberg, Anders. An overview of models of technological singularity

- ↑ "h+ Magazine | Covering technological, scientific, and cultural trends that are changing human beings in fundamental ways". Hplusmagazine.com. Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- ↑ Ćirković, Milan M. "Resource letter: PEs-1: physical eschatology." American Journal of Physics 71.2 (2003): 122-133.

- ↑ Baum, Seth D. "Is humanity doomed? Insights from astrobiology." Sustainability 2.2 (2010): 591-603.

- ↑ Zeilik, M.A.; Gregory, S.A. (1998). Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics (4th ed.). Saunders College Publishing. p. 322. ISBN 0-03-006228-4.

Further reading

- Craig C. Hill, In God's Time: The Bible and the Future, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 2002. ISBN 0-8028-6090-7

- Dave Hunt, A Cup of Trembling, Harvest House Publishers, Eugene, (Oregon) 1995 ISBN 1-56507-334-7.

- Jonathan Menn, Biblical Eschatology, Eugene, Oregon, Wipf & Stock 2013. ISBN 978-1-62032-579-7.

- Joseph Ratzinger., Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press 1985. ISBN 978-0-8132-1516-7.

- Robert Sungenis, Scott Temple, David Allen Lewis, Shock Wave 2000! subtitled The Harold Camping 1994 Debacle, New Leaf Press, Inc. 2004 ISBN 0-89221-269-1

- Stephen Travis, Christ Will Come Again: Hope for the Second Coming of Jesus,Toronto: Clements Publishing 2004. ISBN 1-894667-33-6

- Jerry L. Walls (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology, New York: Oxford University Press 2008. ISBN 978-0-19-973588-4

External links

-

The dictionary definition of eschatology at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of eschatology at Wiktionary -

Works related to Eschatology at Wikisource

Works related to Eschatology at Wikisource -

Media related to Eschatology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Eschatology at Wikimedia Commons