Beyond Capricorn

| |

| Author | Peter Trickett |

|---|---|

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Australian History |

| Publisher | East Street Publications |

Publication date | 2007 |

| ISBN | 978-0-9751145-9-9 |

| OCLC | 182058416 |

| 919.4041 22 | |

| LC Class | DU98.1 .T75 2007 |

Beyond Capricorn: How Portuguese adventurers secretly discovered and mapped Australia and New Zealand 250 years before Captain Cook is a 2007 book by journalist Peter Trickett on the theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia. Although its thesis is similar to that advanced by Kenneth McIntyre in 1977,[1] Lawrence Fitzgerald in 1984[2] and others, the publisher and some news reports[3] presented it as being a new theory on the discovery of Australia.[4]

Historical scholars, including Flinders University Associate Professor Bill Richardson,[5] generally reject the premise on which the book is based, pointing out that only circumstantial evidence has been presented which supports the theory.[6][7][8][9]

The book has been translated into Portuguese.[10] On 8 May 2008 the colloquium of specialists in Portuguese maritime history, "Os Portugueses na Austrália", was held at the Science Museum of the University of Coimbra in Portugal, to discuss Beyond Capricorn. The consensus of the experts was expressed by the chair of the colloquium, Francisco Domingues, who said: "the Portuguese went to Australia but Australia did not at all interest them", and "the Portuguese went to Australia; the English discovered it (in the sense of having given to it a place in the community of nations)".[11] In 2013 the essays, opinions and discussions presented on the colloquium were collected in a book entitled "Portugueses na Austrália", published by Coimbra University Press.[12]

Synopsis

The title of the book refers to the sixteenth century Dieppe maps of France which in part show land in a continent extending south of the Tropic of Capricorn that is in the area of Australia. Trickett claims that the Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover Australia, between 1519–23, well before the first recognised landfall of Europeans in Australia in 1606 by Willem Janszoon. According to Trickett, a 1520 expedition searching for gold and led by Diogo Pacheco (a relative of Duarte Pacheco), may have been the first Europeans to sight Australia, in the present-day Kimberley region of Western Australia. Using an account from João de Barros's Décadas da Ásia, a 1786 history of the Portuguese empire in Asia, Trickett argues Pacheco was killed at Napier Broome Bay, in a battle with Aborigines.[13] Trickett claims the Carronade Island cannons originate from this voyage.[14]

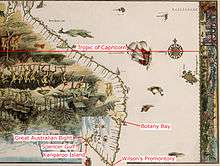

Most of the book, however, focuses on the claimed voyage of a fleet of four ships commanded by Cristóvão de Mendonça, along the eastern and southern coasts of Australia then to New Zealand shortly afterwards, and another Portuguese voyage along the west coast. Trickett uses one of the Dieppe maps in the highly decorated "Vallard" atlas of 1547 to demonstrate this. Trickett claims that Mendonça travelled down the east coast of Australia, sailing into Botany Bay and then around Wilsons Promontory to Kangaroo Island, before returning to Portuguese-controlled Malacca via the North Island of New Zealand. He also claims the Portuguese charted the Western Australian coast, as far south as the southwest tip of Australia. Trickett claims that the French Vallard maps[15] were composed of several portolan charts that were incorrectly assembled from now lost Portuguese charts. Trickett adjusts parts of the Vallard maps by rotating them 90 degrees, giving what he claims is a remarkably accurate depiction of Australia's eastern, southern, and western coasts.

Trickett goes through almost every written location on the Vallard maps, giving an English translation and explaining where he believes the place is located. He also mentions the mythical Mahogany Ship, the ruins at Bittangabee Bay on the south coast of New South Wales, various Aboriginal legends and alleged linguistic similarities, and various artefacts found in Queensland and New Zealand which he claims pre-date known European exploration, as further evidence of a Portuguese discovery of Australia and New Zealand.[16]

An example: Botany Bay

In the publicity campaign surrounding the release of the book, several media reports mentioned Trickett’s claim that the Vallard map accurately showed Botany Bay to the point where Sydney Airport runways could be drawn on it.[17] Trickett’s Botany Bay is "Baia Neve" on the Vallard Map, and on p. 155 Trickett provides a sketch map of the bay with Sydney Airport runways drawn on it to the same scale. He acknowledges the bay is "too large to be Botany Bay in relation to the scale of the Vallard map as a whole".[18] He explains that sixteenth century map-makers "enlarge(d) … important sections of their charts," [19] such as this bay, hence its exaggerated size. The Vallard map original also shows two large islands in the bay and seven islands just outside the mouth of the bay. Trickett identified the islands inside the bay as Bare Island and a large mudflat, drying out at low tide, which he believed appeared as a large island to the Portuguese explorers. The seven islands outside the bay he identifies as a misplacing of the Five Islands Group (50 km away near Wollongong); a representation of the North Head of Sydney Harbour and a representation of Cape Three Points (now Boudi, 70 km away near Broken Bay).

Criticism of Trickett's theories

Following its initial reception online and in the popular press, a number of criticisms of the book have appeared, by scholars including Associate Professor (Spanish and Portuguese) W.A.R. "Bill" Richardson.[5] Trickett repeatedly criticises "orthodox academics" for ignoring or denigrating the theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia,[20] while acknowledging that the book is "not written as an academic treatise—it is aimed at a wider audience".[21]

Trickett’s approach of using only one Dieppe map as the basis for his book, without significant reference to any of the other existing Dieppe maps, has been questioned.[9] The Vallard map of 1547 is not the first of the Dieppe maps, and Richardson argues Trickett incorrectly "assumes the unknown Vallard cartographer had access to much more information" because it contains more place names.[5] Richardson adds that "the hybrid inscriptions [of the Vallard] are in an astonishing jumble of languages", many of which Trickett misreads or misinterprets; suggesting, for example, that the island Illa do Aljofar may have Polynesian origins.[22][23]

Trickett also reproduces a number of sketch maps, comparing Terra Java/Jave La Grande of the A3-sized pages of the Vallard atlas with modern detailed knowledge of the Australian coast, but without showing any scale. Richardson argues this practice misleads the reader, and he previously argued Kenneth McIntyre’s comparative sketches also misled in the same way.[24] The issues in providing such sketch maps for comparison purposes are highlighted in Trickett’s sketch map copy of Illa Do Magna, which he compares to a rough sketch map of New Zealand’s North Island.[25] Richardson adds that the lack of scale used in Beyond Capricorn’s sketch maps causes the reader "to fail to realise that [Trickett’s adjusted] 'Wilsons Promontory' is some 17 degrees, nearly 2,000 kilometres, south of the real Wilsons Promontory."[5]

Commenting in 1985 on other writers who compared Australia’s coast with the Dieppe Maps, Richardson wrote, "it is difficult not to express admiration for the extreme ingenuity exercised in their endeavours to 'correct' the Jave La Grande outline in order to compel it to conform more closely to the known outline of Australia."[26] Writing in 2007 for an Australian mapmaking journal, he suggested Trickett has also taken an approach of "if evidence does not suit a theory, one solution is to alter it."[5]

In an article in The Globe in 2009, Robert J. King refers to Beyond Capricorn, arguing that Jave la Grande is a theoretical construction, an artifact of 16th century cosmography. He points out that the geographers and map makers of the Renaissance struggled to bridge the gap from the world view inherited from Graeco-Roman antiquity, as set out in Claudius Ptolemy's Geography, and a map of the world that would take account of the new geographical information obtained during the Age of Discoveries. The Dieppe world maps reflected the state of geographical knowledge of their time, both actual and theoretical. Accordingly, Java Major, or Jave la Grande, was shown as a promontory of the undiscovered Antarctic continent of Terra Australis. King argues that Jave la Grande on the Dieppe maps represents one of Marco Polo's pair of Javas (Major or Minor), misplaced far to the south of its actual location and attached to a greatly enlarged Terra Australis; it does not represent Australia, discovered by unknown Portuguese voyagers.[27]

See also

References

- ↑ McIntyre, K.G (1977) The Secret Discovery of Australia, Portuguese ventures 200 years before Cook. Souvenir Press, Menindie ISBN 0-285-62303-6

- ↑ Fitzgerald, L (1984). Java La Grande. The Publishers, Hobart ISBN 0-949325-00-7

- ↑ "An Australian publishing house based in South Australia".

- ↑ See for example Guardian Unlimited, 22 March 2007 Several of these reports also claimed the theory "proved" Cook was not the first to discover Australia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richardson, W.A.R. Yet Another Version of the Portuguese 'Discovery' of Australia [online]. "The Globe",Issue 59; 2007; p 59-60. Availability: ISSN 0311-3930. [cited 9 Jan 09]

- ↑ Phillip Knightley's review in the Sydney Morning Herald

- ↑ "The Map Room - April Fool: Revelations Stun Map Historians (Again)".

- ↑ "A voyage of rediscovery about a voyage of rediscovery". 25 March 2007 – via The Guardian.

- 1 2 Agora, Vol 42, No. 2, 2007. Journal of the History Teacher's Association of Victoria. Book reviews, P.64. ISSN 0044-6726

- ↑ Para além de Capricórnio, Lisboa, Caderno, 2008.

- ↑ Ribeiro, Susana Almeida. "“Os portugueses estiveram na Austrália; os ingleses descobriram-na”".

- ↑ "Universidade de Coimbra - Imprensa da Universidade - Portugueses na Austrália: as primeiras viagens".

- ↑ Trickett, P. (2007) pps 37-70

- ↑ Trickett, P. (2007) pps 39-48. Trickett dismisses the 1980s research into the Carronade Island Cannons by Jeremy Green, see footnote on pps353-355. For Green's 2006 publication on the cannons, which Trickett apparently did not consult, see "An investigation of one of the two bronze guns from Carronade Island, Western Australia"

- ↑ "Digital Scriptorium".

- ↑ "Object: Iron helmet (known as the "Spanish" helmet) - Collections Online - Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa".

- ↑ Reuters report by Michael Perry. Widely copied by other sources on the web.

- ↑ Trickett, P. (2007) p.154-7

- ↑ Trickett. P. (2007) p. 154

- ↑ Trickett, P (2007) p.4-5

- ↑ Trickett, P. (2007) p.7

- ↑ Trickett, P. (2007) p.256

- ↑ Richardson points out the word is Portuguese, of Arabic origin, meaning ‘pearl’ and thus strongly connecting it to Hainan island.

- ↑ Richardson, W.A.R. (2006) Was Australia Charted before 1606? The Jave La Grande Inscriptions. National Library of Australia. p. 48-51 ISBN 0-642-27642-0

- ↑ Trickett, P. (2007) p.232. Compare the sketch of Illa Do Magna, its scale and orientation, and the treatment of the "Taranaki" section, with the Vallard original

- ↑ Richardson, W.A.R, (1985) Another Gospel on our discovery by the Portuguese. The Age, 5 January 1985.

- ↑ Robert J. King, "The Jagiellonian Globe, a Key to the Puzzle of Jave la Grande", The Globe: Journal of the Australian Map Circle, no.62, 2009, pp.1-50. http://search.informit.com.au/fullText;dn=991081461781028;res=IELHSS

External links

- Images of the Vallard atlas (1547) at the Huntington Library

- CNN News - Author: Map proves Portuguese discovered Australia

- News.com.au Map 'shows Cook wasn't first

- Reuters, Map proves Portuguese discovered Australia: new book