Bevin Boys

Bevin Boys were young British men conscripted to work in the coal mines of the United Kingdom, between December 1943 and March 1948.[1] Chosen by lot as ten percent of all male conscripts aged 18–25, plus some volunteering as an alternative to military conscription, nearly 48,000 Bevin Boys performed vital and dangerous, but largely unrecognised service in coal mines. Many of them were not released from service until well over two years after the Second World War ended.

Creation of programme

The programme was named after Ernest Bevin, a former trade union official and then British Labour Party politician who was Minister of Labour and National Service in the wartime coalition government. At the beginning of the war the Government, underestimating the value of strong younger coal miners, conscripted them into the armed forces. By mid-1943 the coal mines had lost 36,000 workers, and they were generally not replaced, because other likely young men were also being conscripted to the armed forces. The government made a plea to men liable to conscription, asking them to volunteer to work in the mines, instead, but few responded, and the manpower shortage continued.

By October 1943 Britain was becoming desperate for a continued supply of coal, both for the industrial war effort and for keeping homes warm throughout the winter. On 12 October Gwilym Lloyd-George, Minister of Fuel and Power, announced in the House of Commons that some conscripts would be directed to the mines. On 2 December Ernest Bevin explained the scheme in more detail. The colloquial name "Bevin Boys" came from a further speech Bevin made:

We need 720,000 men continuously employed in this industry. This is where you boys come in. Our fighting men will not be able to achieve their purpose unless we get an adequate supply of coal.

From 1943 to 1945 one in ten of young men called up was sent to work in the mines. This caused a deal of upset, as many young men wanted to join the fighting forces and felt that as miners they would not be valued. Many Bevin Boys suffered taunts as they wore no uniform, and were wrongly assumed by some thoughtless people to be deliberately avoiding military conscription.

Programme

Selection of conscripts

To make the process random, one of Bevin's secretaries each week, from 14 December 1943, pulled a digit from a hat containing all ten digits, 0–9, and all men liable for call-up that week whose National Service registration number ended in that digit were directed to work in the mines, with the exception of any selected for highly skilled war work such as flying planes and in submarines, and men found physically unfit for mining. Conscripted miners came from many different trades and professions, from desk work to heavy manual labour, and included some who might otherwise have become commissioned officers.

Working conditions

The Bevin Boys were first given six weeks' training (four off-site, two on). The work was typical coal mining, largely a mile or more down dark, dank tunnels, and conscripts were supplied with helmets and steel-capped safety boots. Bevin Boys did not wear uniforms or badges, but the oldest clothes they could find. Being of military age and without uniform caused many to be stopped by police and questioned about avoiding call-up.[2]

Since a number of conscientious objectors were sent to work down the mines as an alternative to military service (under a system wholly separate from the Bevin Boy programme), there was sometimes an assumption that Bevin Boys were "Conchies". The right to conscientiously object to military service for philosophical or religious reasons was recognised in conscription legislation, as it had been in the First World War. However, old attitudes still prevailed amongst some members of the general public, with resentment by association towards Bevin Boys. In 1943 Ernest Bevin said in Parliament: "There are thousands of cases in which conscientious objectors, although they may have refused to take up arms, have shown as much courage as anyone else in Civil Defence."[3]

End of programme

The Bevin Boy programme was wound up in 1948. At that time the Bevin Boys received neither medals nor the right to return to the jobs they had held previously, unlike armed forces personnel. Bevin Boys were not fully recognised as contributors to the war effort until 1995, 50 years after VE Day, in a speech by Queen Elizabeth II.

On 20 June 2007, Tony Blair informed the House of Commons during Prime Minister's Questions that thousands of conscripts who worked down mines during the Second World War would receive an honour. The prime minister told the Commons the Bevin Boys would be rewarded with a Veterans Badge similar to the HM Armed Forces Badge awarded by the Ministry of Defence.[4]

The first badges were awarded on 25 March 2008 by the then Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, at a reception in 10 Downing Street, marking the 60th anniversary of discharge of the last Bevin Boys.

Historic responsibility within government for the Bevin Boys lies with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

The Bevin Boys Association is trying to trace all 48,000 Bevin Boy conscripts, optants or volunteers who served in Britain's coal mines during and after the war, from 1943 to 1948.[5]

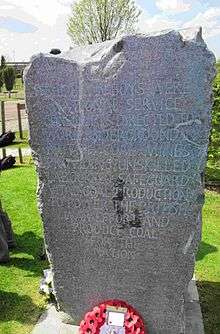

On Tuesday 7 May 2013, a memorial to the Bevin Boys, based on the Bevin Boys Badge, was unveiled by the Countess of Wessex at the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, Staffordshire. The memorial was designed by former Bevin Boy Harry Parkes; it is made of four stone plinths carved from grey Kilkenny stone from the Republic of Ireland. The stone should turn black like the coal that the miners extracted.[6]

Notable Bevin Boys

- Peter Archer, lawyer and Labour Party politician

- Stanley Bailey, constable

- John Comer, actor[7]

- Roy Grantham, trade union leader

- (Lord) Paul Hamlyn,[8] founder of the Hamlyn group of publishers and Music for Pleasure record label

- Nat Lofthouse, footballer[9]

- Dickson Mabon, politician

- Eric Morecambe,[10] comedian

- Alun Owen, screenwriter

- Jimmy Savile,[10][11] disgraced DJ & TV personality

- Kenneth Partridge, interior designer[12]

- Jock Purdon,[13] folk singer/poet

- Peter Alan Rayner, numismatic author

- Brian Rix,[10] actor/manager, and president of Mencap

- Peter Shaffer,[14] dramatist

- Alf Sherwood, footballer

- Gerald Smithson, cricketer

In popular culture

Douglas Livingstone's radio play, Road to Durham, is a fictional account of two former Bevin Boys, now in their eighties, as they visit the Durham Miners' Gala.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ Bevin Boys – BERR Archived 14 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Called Up Sent Down : The Bevin Boys' War – Tom Hickman Pub. The History Press 2008 ISBN 0-7509-4547-8

- ↑ 1940–1949 Candles in the Dark , Peace Pledge Union

- ↑ The debate can be found here.

- ↑ "Bevin Boys Association entry on Culture24". Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ↑ "Bevin Boys memorial unveiled by Countess of Wessex". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ↑ http://afternoontea.mpt.org/tea-time-tidbits/060914/

- ↑ Mosse, Werner Eugen; Carlebach, Julius. Second chance: two centuries of German-speaking Jews in the United Kingdom. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 376–. ISBN 9783161457418. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Bolton Council-Bolton's Bevin Boys remembered". Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Cooke, Ken (2007). History of the Percy Jackson Grammar School: Adwick-le-street, Doncaster, Yorkshire, 1939–1968 : Recollections of Schooldays of the 1940s, 1950s & 1960s. Troubador Publishing Ltd. pp. 6–. ISBN 9781905886784. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Fox, Margalit (2 November 2011). "Jimmy Savile, TV Personality, Dies at 84". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ "Kenneth Partridge, interior designer – obituary". Telegraph.co.uk. 21 December 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ English Dance & Song. 41–44. English Folk Dance and Song Society. 1979. p. 18.

- ↑ Morton, Ray (2011-02-01). Amadeus: Music on Film Series. Hal Leonard. pp. 21–. ISBN 9780879104177. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Giddings, Robert (30 April 2009). "RADIO: Seamless drama goes underground to dig deep for victory". Tribune. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bevin Boys. |

- Wartime Memories – Bevin Boys and their recognition

- The Bevin Boys in Bures. Suffolk

- A short film about the Bevin Boys