Azekah

| עזקה | |

|

Tel Azekah | |

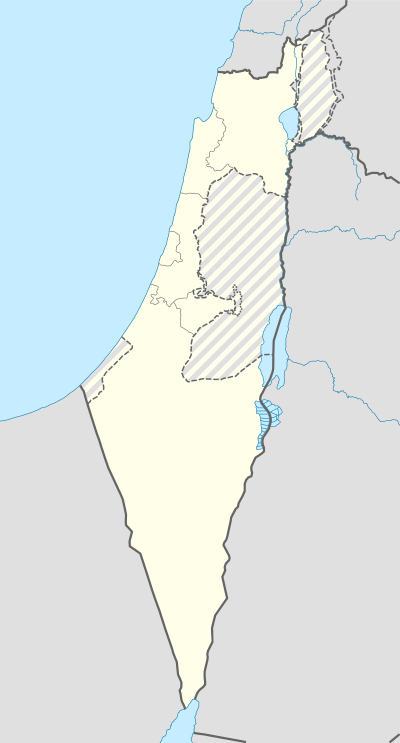

Shown within Israel | |

| Alternate name | Tel Azeka |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 31°42′01″N 34°56′08″E / 31.700348°N 34.9356651°E |

Azekah (Hebrew: עזקה, ʿazeqah) was a town in the Shephelah guarding the upper reaches of the Valley of Elah, about 26 km (16 mi) northwest of Hebron. The current tell (ruin) by that name has been identified with the biblical Azekah, dating back to the Canaanite period. Today, the site lies on the purlieu of Britannia Park.[1] According to Epiphanius of Salamis, the name meant "white" in the Canaanite tongue.[2] The tell is pear shaped with the tip pointing northward. Due to its location in the Elah Valley it functioned as one of the main Judahite border cities, sitting on the boundary between the lower and higher Shephelah.[3] Although listed in Joshua 15:35 as being a city in the plain, it is actually partly in the hill country, partly in the plain.

Biblical history

In the Bible, it is said to be the place where the Amorite kings were defeated by Joshua, and their army destroyed by a hailstorm (Joshua 10:10-11). It was given to the tribe of Judah (Joshua 15:20). In the time of Saul, the Philistines massed their forces between Sokho and Azekah, putting forth Goliath as their champion (1 Samuel 17). Rehoboam fortified the town in his reign, along with Lachish and other strategic sites (2 Chronicles 11:5-10). Lachish and Azekah were the last two towns to fall to the Babylonians before the overthrow of Jerusalem itself (Jeremiah 34:6-7). It was one of the places re-occupied by the people on the return from the Captivity (Nehemiah 11:30).

Identification

Although the hill is now widely known as the Tel (ruin) of Azekah, in the early 19th-century the hilltop ruin was known locally by the name of Tell Zakariyeh.[4][5] In 1838, British-American explorer Edward Robinson passed by the site of Tell Zakariyeh, which stood to the left of the modern village bearing the same name.[6] French explorer Victor Guérin thought Tell Zakariyeh to be the village mentioned in the Book of I Maccabees (6:32), known then as Beit Zakariah.[7][8] "As for Azekah," Guérin writes, "it has not yet been found with certainty, this name appearing to have disappeared."[9] Scholars believe that the town's old namesake was changed at some early time in Jewish history.

In the mosaic layout of the Madaba Map of the 5th century CE, the site is mentioned in conjoined Greek uncials: Το[ποθεσία] του Αγίου Ζαχαρίου, Βεθζαχαρ[ίου] (= [The] site of St. Zacharias, Beth Zachar[ias]). Epiphanius of Salamis writes that, in his day, Azekah was already called by the Syriac name Ḥǝwarta.[10]

Non-Biblical mention

Azekah is mentioned in two sources outside of the Bible. A text from the Assyrian king Sennacherib describes Azekah and its destruction during his military campaign.

- (3) […Ashur, my lord, encourage]ed me and against the land of Ju[dah I marched. In] the course of my campaign, the tribute of the kings of Philistia? I received…

- (4) […with the mig]ht of Ashur, my lord, the province of [Hezek]iah of Judah like […

- (5) […] the city of Azekah, his stronghold, which is between my [bo]rder and the land of Judah […

- (6) [like the nest of the eagle? ] located on a mountain ridge, like pointed iron daggers without number reaching high to heaven […

- (7) [Its walls] were strong and rivaled the highest mountains, to the (mere) sight, as if from the sky [appears its head? …

- (8) [by means of beaten (earth) ra]mps, mighty? battering rams brought near, the work of […], with the attack by foot soldiers, [my] wa[rriors…

- (9) […] they had seen [the approach of my cav]alry and they had heard the roar of the mighty troops of the god Ashur and [their] he[arts] became afraid […

- (10) [The city Azekah I besieged,] I captured, I carried off its spoil, I destroyed, I devastated, [I burned with fire…[11]

Azekah is also mentioned in one of the Lachish letters. Lachish Letter 4 suggests that Azekah was destroyed, as they were no longer visible to the exporter of the letter. Part of the otracon reads:

- "And inasmuch as my lord sent to me concerning the matter of Bet Harapid, there is no one there. And as for Semakyahu, Semayahu took him and brought him up to the city. And your servant is not sending him there any[more -], but when morning comes round [-]. And may (my lord) be apprised that we are watching for the fire signals of Lachish according to all the signs which my lord has given, because we cannot see Azeqah."[12]

Archaeological findings

Excavations by the English archeologists Frederick J. Bliss and R. A. Stewart Macalister in the period 1898-1900 at Tel Azekah revealed a fortress, water systems, hideout caves used during Bar Kokhba revolt and other antiquities, such as LMLK seals. Azekah was one of the first sites excavated in the Holy Land and was excavated under the Palestine Exploration Fund for a period of 17 weeks over the course of three seasons.[13] At the close of their excavation Bliss and Macalister refilled all of their excavation trenches in order to preserve the site.[14] The site is located on the grounds of a Jewish National Fund park, Britannia Park.[15]

The Lautenschläger Azekah Expedition, part of the regional Elah Valley Project, commenced in the summer of 2012. It is directed by Prof. Oded Lipschits of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, together with Dr Yuval Gadot of TAU and with Prof. Manfred Oeming of Heidelberg University. and is a consortium of over a dozen universities from Europe, North America, and Australia. In its first season 300 volunteers worked for six weeks and uncovered walls, installations, and many hundreds of artifacts. As part of the Jewish National Fund park, whenever possible structures will be conserved and displayed to the public.

External links

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tel Azeka. |

- ↑ Tel Azeka and Google Map

- ↑ Epiphanius' Treatise on Weights and Measures (Syriac version), ed. James Elmer Dean, Chicago University Press: Chicago 1935, Concerning Names of Places, section no. 64.

- ↑ http://www.academia.edu/2400278/TEL_AZEKAH_113_YEARS_AFTER_Preliminary_Evaluation_of_the_Renewed_Excavations_at_the_Site

- ↑ Preliminary Evaluation of the Renewed Excavations at the Site

- ↑ Erich Zenger, Einleitung in das Alte Testament, p. 721

- ↑ Edward Robinson, Biblical Researches in Palestine, vol. II, section XI, London 1856, pp. 16, 21

- ↑ Victor Guérin, Description de la Palestine, Judée, Description de la Judée, Paris 1869, pp. 316–319; See: Guérin, Victor (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities (Book xii, chapter ix, verse 4)

- ↑ Victor Guérin, Description de la Palestine, Judée, Description de la Judée, Paris 1869, p. 333. Original French: "Quant à Azéca, en hébreu A’zekah, elle n’a pas encore été retrouvée d’une manière certaine, ce nom paraissant avoir disparu."

- ↑ Epiphanius' Treatise on Weights and Measures (Syriac version), ed. James Elmer Dean, Chicago University Press: Chicago 1935, p. 72 (§ 64)

- ↑ Na’aman, N. Sennacherib’s "Letter to God" on His Campaign to Judah. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 214:25-39. 1974 from Lipschitz, Tel Azekah 113

- ↑ Aḥituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past. Jerusalem: CARTA Jerusalem, 2008, pg. 70. From Lachish letters

- ↑ http://www.academia.edu/2400278/TEL_AZEKAH_113_YEARS_AFTER_Preliminary_Evaluation_of_the_Renewed_Excavations_at_the_Site

- ↑

- ↑ Archaeological mounds