Beta-glucan

β-Glucans (beta-glucans) comprise a group of β-D-glucose polysaccharides naturally occurring in the cell walls of cereals, bacteria, and fungi, with significantly differing physicochemical properties dependent on source. Typically, β-glucans form a linear backbone with 1-3 β-glycosidic bonds but vary with respect to molecular mass, solubility, viscosity, branching structure, and gelation properties, causing diverse physiological effects in animals.

Various studies have examined the potential health effects of β-glucan. Oat fiber β-glucan at intake levels of at least 3 g per day can decrease the levels of saturated fats in the blood and may reduce the risk of heart disease. Some studies have suggested that cereal-derived β-glucan may also have immunomodulatory properties. Yeast- and medicinal mushroom-derived β-glucans have been investigated for their ability to modulate the immune system. β-glucans are further used in various nutraceutical and cosmetic products, as texturing agents, and as soluble fiber supplements, but can be problematic in the process of brewing.

History

Cereal and fungal products have been used for centuries for medicinal and cosmetic purposes; however, the specific role of β-glucan was not explored until the 20th century. β-glucans were first discovered in lichens, and shortly thereafter in barley. A particular interest in oat β-glucan arose after their cholesterol lowering effect was reported in 1984.[1][2]

In 1997, the FDA approved of a claim that intake of at least 3 g of β-glucan from oats per day decreased saturated fats and reduced the risk of heart disease.

Structure

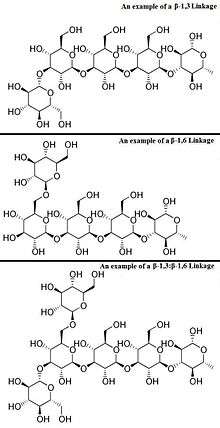

Glucans are arranged in six-sided D-glucose rings connected linearly at varying carbon positions depending on the source, although most commonly β-glucans include a 1-3 glycosidic link in their backbone. Although technically β-glucans are chains of D-glucose polysaccharides linked by β-type glycosidic bonds, by convention not all β-D-glucose polysaccharides are categorized as β-glucans.[3] Cellulose is not typically considered a β-glucan, as it is insoluble and does not exhibit the same physicochemical properties as other cereal or yeast β-glucans.[4]

Some β-glucan molecules have branching glucose side-chains attached to other positions on the main D-glucose chain, which branch off the β-glucan backbone. In addition, these side-chains can be attached to other types of molecules, like proteins, as in polysaccharide-K.

The most common forms of β-glucans are those comprising D-glucose units with β-1,3 links. Yeast and fungal β-glucans contain 1-6 side branches, while cereal β-glucans contain both β-1,3 and β-1,4 backbone bonds. The frequency, location, and length of the side-chains may play a role in immunomodulation. Differences in molecular weight, shape, and structure of β-glucans dictate the differences in biological activity.[2][5]

| Source | Backbone | Branching | Solubility in Water |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria |  |

None | Insoluble[6] |

| Fungus |  |

Short β-1,6 branching | Insoluble[7] |

| Yeast |  |

Long β-1,6 branching | Insoluble[5] |

| Cereal |  |

None | Soluble[2] |

β-glucan types

β-glucans form a natural component of the cell walls of bacteria, fungi, yeast, and cereals such as oat and barley. Each type of beta-glucan comprises a different molecular backbone, level of branching, and molecular weight which effects its solubility and physiological impact. One of the most common sources of β(1,3)D-glucan for supplement use is derived from the cell wall of baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). The β(1,3)D-glucans from yeast are often insoluble. However, β(1,3)(1,4)-glucans are also extracted from the bran of some grains, such as oats and barley, and to a much lesser degree in rye and wheat. Other sources include some types of seaweed,[8] and various species of mushrooms, such as reishi, Ganoderma applanatum,[9] shiitake, Chaga and maitake.[10]

Cereal β-Glucans

Cereal β-glucans from oat, barley, wheat, and rye induce a variety of physiological effects that positively impact health. Barley and oat β-glucans have been studied for their effects on blood glucose regulation in test subjects with hypercholesterolemia.[11]

Oats and barley differ in the ratio of trimer and tetramer 1-4 linkages. Barley has more 1-4 linkages with a degree of polymerization higher than 4. However, the majority of barley blocks remain trimers and tetramers. In oats, β-glucan is found mainly in the endosperm of the oat kernel, especially in the outer layers of that endosperm.[2]

Mushroom β-glucans

β-D-glucans form part of the cell wall of certain fungi, especially Aspergillus and Agaricus species. Mushroom beta-glucans are linked by 1,3 glycosidic bonds with 1,6 branches.

Yeast β-Glucans

β-Glucans found in the cell walls of yeast contain a 1,3 carbon backbone with elongated 1,6 carbon branches[12] A series of human clinical trials in the 1990s evaluated the impact of PGG-glucan on infections in high-risk surgical patients. In these studies, PGG-glucan significantly reduced complications.[13][14][15][16] Orally administered yeast-glucan was reported to decrease the levels of IL-4 and IL-5 cytokines responsible for the clinical manifestation of allergic rhinitis, while increasing the levels of IL-12.[17]

β-Glucan absorption

Enterocytes facilitate the transportation of β(1,3)-glucans and similar compounds across the intestinal cell wall into the lymph, where they begin to interact with macrophages to activate immune function.[18] Radiolabeled studies have verified that both small and large fragments of β-glucans are found in the serum, which indicates that they are absorbed from the intestinal tract.[19] M cells within the Peyer’s patches physically transport the insoluble whole glucan particles into the gut-associated lymphoid tissue.[20]

(1,3)-β-D-glucan medical application

An assay to detect the presence of (1,3)-β-D-glucan in blood is marketed as a means of identifying invasive or disseminated fungal infections.[21][22][23] This test should be interpreted within the broader clinical context, however, as a positive test does not render a diagnosis, and a negative test does not rule out infection. False positives may occur because of fungal contaminants in the antibiotics amoxicillin-clavulanate,[24] and piperacillin/tazobactam. False positives can also occur with contamination of clinical specimens with the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Alcaligenes faecalis, which also produce (1→3)β-D-glucan.[25] This test can aid in the detection of Aspergillus, Candida, and Pneumocystis jirovecii.[26][27][28] This test cannot be used to detect Mucor or Rhizopus, the fungi responsible for mucormycosis, as they do not produce (1,3)-beta-D-glucan.[29]

See also

References

- ↑ Anderson, James D (1984). "Hypocholesterolemic effects of oat-bran or bean intake for hypercholesterolemic men". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

- 1 2 3 4 Chu, YiFang (2014). Oats Nutrition and Technology. Barrington, Illinois: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-35411-7.

- ↑ Zeković, Djordje B. (10 October 2008). "Natural and Modified (1→3)-β-D-Glucans in Health Promotion and Disease Alleviation". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology.

- ↑ Sikora, Per (14 June 2012). "Identification of high b-glucan oat lines and localization and chemical characterization of their seed kernel b-glucans". Food Chemistry.

- 1 2 Volman, Julia J (20 November 2007). "Dietary modulation of immune function by β-glucans". Physiology & Behaviour.

- ↑ Mcintosh, M (19 October 2004). "Curdlan and other bacterial (1→3)-β-D-glucans". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology.

- ↑ Han, Man Deuk (March 2008). "Solubilization of water-insoluble β-glucan isolated from Ganoderma lucidum". Journal of Environmental Biology.

- ↑ Teas, J (1983). "The dietary intake of Laminarin, a brown seaweed, and breast cancer prevention". Nutrition and Cancer. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 4 (3): 217–222. ISSN 0163-5581. PMID 6302638. doi:10.1080/01635588209513760.

- ↑ "Isolation and characterization of antitumor active β-d-glucans from the fruit bodies of Ganoderma applanatum". Carbohydrate Research. 115, 16 April 1983: 273–280. doi:10.1016/0008-6215(83)88159-2.

- ↑ Wasser, SP; Weis AL (1999). "Therapeutic effects of substances occurring in higher Basidiomycetes mushrooms: a modern perspective". Critical Reviews in Immunology. United States: Begell House. 19 (1): 65–96. ISSN 1040-8401. PMID 9987601. doi:10.1615/critrevimmunol.v19.i1.30.

- ↑ Keogh, GF; Cooper GJ; Mulvey TB; McArdle BH; Coles GD; Monro JA; Poppitt SD (October 2003). "Randomized controlled crossover study of the effect of a highly beta-glucan-enriched barley on cardiovascular disease risk factors in mildly hypercholesterolemic men". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. United States: American Society of Clinical Nutrition. 78 (4): 711–718. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 14522728.

- ↑ Manners, David J. (2 February 1973). "The Structure of a β-(1->3)-D-Glucan from Yeast Cell Walls". Biochemical Journal. PMC 1165784

. doi:10.1042/bj1350019.

. doi:10.1042/bj1350019. - ↑ Babineau, TJ; Marcello P; Swails W; Kenler A; Bistrian B; Forse RA (November 1994). "Randomized phase I/II trial of a macrophage-specific immunomodulator (PGG-glucan) in high-risk surgical patients". Annals of Surgery. United States: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 220 (5): 601–609. PMC 1234447

. PMID 7979607. doi:10.1097/00000658-199411000-00002.

. PMID 7979607. doi:10.1097/00000658-199411000-00002. - ↑ Babineau, TJ; Hackford A; Kenler A; Bistrian B; Forse RA; Fairchild PG; Heard S; Keroack M; Caushaj P; Benotti P (November 1994). "A phase II multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of three dosages of an immunomodulator (PGG-glucan) in high-risk surgical patients". Archives of Surgery. United States: American Medical Association. 129 (11): 1204–1210. ISSN 0004-0010. PMID 7979954. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420350102014.

- ↑ Dellinger EP, Babineau TJ, Bleicher P, Kaiser AB, Seibert GB, Postier RG, Vogel SB, Norman J, Kaufman D, Galandiuk S, Condon RE (September 1999). "Effect of PGG-glucan on the rate of serious postoperative infection or death observed after high-risk gastrointestinal operations. Betafectin Gastrointestinal Study Group". Archives of Surgery. United States: American Medical Association. 134 (9): 977–983. PMID 10487593. doi:10.1001/archsurg.134.9.977.

- ↑ Browder, W; Williams D; Pretus H; Olivero G; Enrichens F; Mao P; Franchello A (May 1990). "Beneficial effect of enhanced macrophage function in the trauma patient". Annals of Surgery. United States: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 211 (5): 605–612; discussion 612–613. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1358234

. PMID 2111126.

. PMID 2111126. - ↑ Kirmaz, C; Bayrak P; Yilmaz O; Yuksel H. (June 2005). "Effects of glucan treatment on the Th1/Th2 balance in patients with allergic rhinitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled study". European Cytokine Network. France: John Libbey Eurotext. 16 (2): 128–134. ISSN 1148-5493. PMID 15941684.

- ↑ Frey A, Giannasca KT, Weltzin R, Giannasca PJ, Reggio H, Lencer WI, Neutra MR (1996-09-01). "Role of the glycocalyx in regulating access of microparticles to apical plasma membranes of intestinal epithelial cells: implications for microbial attachment and oral vaccine targeting". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. United States: Rockefeller University Press. 184 (3): 1045–1059. PMC 2192803

. PMID 9064322. doi:10.1084/jem.184.3.1045.

. PMID 9064322. doi:10.1084/jem.184.3.1045. - ↑ Tsukagoshi S, Hashimoto Y, Fujii G, Kobayashi H, Nomoto K, Orita K (June 1984). "Krestin (PSK)". Cancer Treatment Reviews. England: Saunders. 11 (2): 131–155. PMID 6238674. doi:10.1016/0305-7372(84)90005-7.

- ↑ Hong, F; Yan J; Baran JT; Allendorf DJ; Hansen RD; Ostroff GR; Xing PX; Cheung NK; Ross GD (2004-07-15). "Mechanism by which orally administered β-1,3-glucans enhance the tumoricidal activity of antitumor monoclonal antibodies in murine tumor models". Journal of Immunology. United States: American Association of Immunologists. 173 (2): 797–806. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 15240666. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.797.

- ↑ Obayashi T, Yoshida M, Mori T, et al. (1995). "Plasma (13)-beta-D-glucan measurement in diagnosis of invasive deep mycosis and fungal febrile episodes". Lancet. 345 (8941): 17–20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91152-9.

- ↑ Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Alexander BD, Kett DH, et al. (2005). "Multicenter clinical evaluation of the (1→3)β-D-glucan assay as an aid to diagnosis of fungal infections in humans". Clin Infect Dis. 41 (5): 654–659. PMID 16080087. doi:10.1086/432470.

- ↑ Odabasi Z, Mattiuzzi G, Estey E, et al. (2004). "Beta-D-glucan as a diagnostic adjunct for invasive fungal infections: validation, cutoff development, and performance in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome". Clin Infect Dis. 39 (2): 199–205. PMID 15307029. doi:10.1086/421944.

- ↑ Mennink-Kersten MA, Warris A, Verweij PE (2006). "1,3-β-D-Glucan in patients receiving intravenous amoxicillin–clavulanic acid". NEJM. 354 (26): 2834–2835. PMID 16807428. doi:10.1056/NEJMc053340.

- ↑ Mennink-Kersten MA, Ruegebrink D, Verweij PE (2008). "Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a cause of 1,3-β-D-glucan assay reactivity". Clin Infect Dis. 46 (12): 1930–1931. PMID 18540808. doi:10.1086/588563.

- ↑ Lahmer, Tobias; da Costa, Clarissa Prazeres; Held, Jürgen; Rasch, Sebastian; Ehmer, Ursula; Schmid, Roland M.; Huber, Wolfgang (2017-04-04). "Usefulness of 1,3 Beta-D-Glucan Detection in non-HIV Immunocompromised Mechanical Ventilated Critically Ill Patients with ARDS and Suspected Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia". Mycopathologia. ISSN 1573-0832. PMID 28378239. doi:10.1007/s11046-017-0132-x.

- ↑ He, Song; Hang, Ju-Ping; Zhang, Ling; Wang, Fang; Zhang, De-Chun; Gong, Fang-Hong (August 2015). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of serum 1,3-β-D-glucan for invasive fungal infection: Focus on cutoff levels". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection = Wei Mian Yu Gan Ran Za Zhi. 48 (4): 351–361. ISSN 1995-9133. PMID 25081986. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2014.06.009.

- ↑ Kullberg, Bart Jan; Arendrup, Maiken C. (2015-10-08). "Invasive Candidiasis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 373 (15): 1445–1456. ISSN 1533-4406. PMID 26444731. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1315399.

- ↑ Ostrosky-Zeichner, Luis; Alexander, Barbara D.; Kett, Daniel H.; Vazquez, Jose; Pappas, Peter G.; Saeki, Fumihiro; Ketchum, Paul A.; Wingard, John; Schiff, Robert (2005-09-01). "Multicenter clinical evaluation of the (1-->3) beta-D-glucan assay as an aid to diagnosis of fungal infections in humans". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (5): 654–659. ISSN 1537-6591. PMID 16080087. doi:10.1086/432470.

External links

- beta-Glucans at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)