Campanology

Campanology (from Late Latin campana, "bell"; and Greek -λογία, -logia) is the study of bells. It encompasses the technology of bells – how they are cast, tuned, rung, and sounded – as well as the history, methods, and traditions of bell-ringing as an art.[1]

It is common to collect together a set of tuned bells and treat the whole as one musical instrument. Such collections – such as a Flemish carillon, a Russian zvon, or an English "ring of bells" used for change ringing – have their own practices and challenges; and campanology is likewise the study of perfecting such instruments and composing and performing music for them.

In this sense, however, the word campanology is most often used in reference to relatively large bells, often hung in a tower. It is not usually applied to assemblages of smaller bells, such as a glockenspiel, a collection of tubular bells, or an Indonesian gamelan.

A campanologist is one who studies campanology, though it is popularly mis-used to refer to a bell ringer.[2]

Carillons

The carillon is a collection of tuned bells for playing conventional melodic music. The bells are stationary and struck by hammers linked to a clavier keyboard.

The instrument is played sitting on a bench by hitting the top keyboard that allows expression through variation of touch, with the underside of the half-clenched fists, and the bottom keyboard with the feet, since the lower notes in particular require more physical strength than an organ, the latter not attaining the tonal range of the better carillons: for some of these, their bell producing the lowest tone, the 'bourdon', may weigh well over 8 tonnes; other fine bells settle for 5 to 6 tonnes. A carillon renders at least two octaves for which it needs 23 bells, though the finest have 47 to 56 bells or extravagantly even more, arranged in chromatic sequence, so tuned as to produce concordant harmony when many bells are sounded together.

Professional Carillonneurs like Belgian Jef Denyn have widespread fame[3]

The oldest are found in church towers in continental northern Europe, especially in cathedral towers in Belgium and present-day northern France, where some (like the St. Rumbolds Cathedral in Mechelen, the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp) became UNESCO World Heritage Sites – classified with the Belfry of Bruges and its municipal Carillon under 'Belfries of Belgium and France'.

The carillon of Kirk in the Hills, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, United States, along with the one at Hyechon College in Daejoen, South Korea, have the highest number of bells in the world: 77.

Modern large carillon edifices have been erected as stand-alone instruments across the world, for instance the Netherlands Carillon at Arlington National Cemetery.

The carillon in the Church of St Peter, Aberdyfi, Gwynedd, Wales is often used to play the famous 'Bells of Aberdovey' tune.

Chimes

A carillon-like instrument with fewer than 23 bells is called a chime. American chimes usually have one to one and a half diatonic octaves. Many chimes play an automated piece of music, such as clock chimes. Chime bells generally used to lack dynamic variation and inner tuning, or the mathematical balance of a bell's complex sound, to permit use of harmony. Since the 20th century, in Belgium and The Netherlands, clock chime bells have inner tuning and produce complex fully harmonized music.[4]

These chimes should not be confused with another musical instrument also called chimes (or tubular bells) nor with a wind chime.

Russian Orthodox bells

The bells in Russian tradition are sounded by their clappers, attached to ropes; a special system of ropes is developed individually for every belltower. All the ropes are gathered in one place, where the bell-ringer stands. The ropes (usually all ropes) are not pulled, but rather pressed with hands or legs. Since one end of every rope is fixed, and the ropes are kept in tension, a press or even a punch on a rope makes a clapper move.

The Russian Tsar Bell is the largest extant bell in the world.

Full circle change ringing

In English style (see below) full circle ringing the bells in a church tower are hung so that on each stroke the bell swings through a complete circle; actually a little more than 360 degrees. Between strokes, it briefly sits poised 'upside-down', with the mouth pointed upwards; pulling on a rope connected to a large diameter wheel attached to the bell swings it down and the assembly's own momentum propels the bell back up again on the other side of the swing. Each alternate pull or stroke is identified as either handstroke or backstroke - handstroke where the "sally" (the fluffy area covered with wool) is pulled followed by a pull on the plain "tail". At East Bergholt in the English county of Suffolk, there is a unique set of bells that are not in a tower and are rung full circle by hand.[5] They are the heaviest ring of five bells listed in Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers[6] at 4.25 tons (4,318 kg) in total.

These rings of bells have relatively few bells, compared with a carillon; six or eight-bell towers are common, with the largest rings in numbering up to sixteen bells. The bells are usually tuned to fall in a diatonic scale without chromatic notes; they are traditionally numbered from the top downwards so that the highest bell (called the treble) is numbered 1 and the lowest bell (the tenor) has the highest number; it is usually the tonic note of the bells' scale.

To swing the heavy bells requires a ringer for each bell. Furthermore, the great inertias involved mean that a ringer has only a limited ability to retard or accelerate his/her bell's cycle. Along with the relatively limited palette of notes available, the upshot is that such rings of bells do not easily lend themselves to ringing melodies.

Instead, a system of change ringing evolved, probably early in the seventeenth century, which centres on mathematical permutations. The ringers begin with rounds, which is simply ringing down the scale in numerical order. (On six bells this would be 123456.) The ringing then proceeds in a series of rows or changes, each of which is some permutation of rounds (for example 214365) where no bell changes by more than one position from the preceding row (this is also known as the Steinhaus–Johnson–Trotter algorithm).

In call change ringing, one of the ringers (known as the Conductor) calls out to tell the other ringers how to vary their order. The timing of the calls and changes of pattern accompanying them are made at the discretion of the Conductor and so do not necessarily involve a change of ringing sequence at each successive stroke as is characteristic of method ringing. Some ringers, notably in the West of England where there is a strong call-change tradition, ring call changes exclusively but for others, the essence of change ringing is the substantially different method ringing. As of 2015 there are 7,140 English style rings. The Netherlands, Pakistan, India, and Spain have one each. The Windward Isles and the Isle of Man have 2 each. Canada and New Zealand 8 each. The Channel Isles 10. Africa as a continent has 13. Scotland 24, Ireland 37, USA 48, Australia 59 and Wales 227. The remaining 6,798 (95.2%) are in England (including three mobile rings).[7]

Method ringing

In method or scientific ringing each ringer has memorized a pattern describing his or her bell's course from row to row; taken together, these patterns (along with only occasional calls made by a conductor) form an algorithm which cycles through the various available permutations dictated by the number of bells available. There are hundreds of these methods which have been composed over the centuries and all have names, some being very fanciful. Better-known examples such as Plain Bob, Reverse Canterbury, Grandsire and Double Oxford are familiar to most ringers.

Serious ringing always starts and ends with rounds; and it must always be true — each row must be unique, never repeated. A performance of a few hundred rows or so is called a touch. A performance of all the possible permutations possible on a set of bells is called an extent, with bells there are ! possible permutations. With five bells 5! = 120 which takes about 5 minutes. With seven bells 7! = 5,040 which takes about three hours to ring. This is the definition of a full peal on 7 (5,000 or more for other numbers of bells.) Less demanding is the quarter peal of 1,260 changes. When ringing peals and quarter peals on fewer bells several complete extents are rung consecutively. When ringing on higher numbers of bells less than a complete extent is rung. On eight bells the extent is 8!=40,320 which has only been accomplished once, taking nearly nineteen hours.

Ringing in English belltowers became a popular hobby in the late 17th century, in the Restoration era; the scientific approach which led to modern method ringing can be traced to two books of that era, Tintinnalogia or the Art of Ringing (published in 1668 by Richard Duckworth and Fabian Stedman) and Campanalogia (also by Stedman; first released 1677; see Bibliography). Today change ringing remains most popular in England but is practiced worldwide; over four thousand peals are rung each year.

Dorothy Sayers's mystery story, "The Nine Tailors" (1934) centers around change ringing of bells in a Fenland church.

Ellacombe apparatus

The Ellacombe apparatus is an English mechanism devised for chiming by striking stationary bells with external hammers. However it does not have the same sound as full circle ringing due to the absence of the doppler effect derived from bell rotation and the lack of a damping effect of the clapper after each strike.

It requires only one person to operate. Each hammer is connected by a rope to a fixed frame in the bell-ringing room. When in use the ropes are taut, and pulling one of the ropes towards the player will strike the hammer against the bell. To enable normal full circle ringing on the same bells, the ropes are slackened to allow the hammers to drop away from the moving bells.

The system was devised by Reverend Henry Thomas Ellacombe of Gloucestershire, who first had such a system installed in Bitton in 1821. He created the system to make conventional bell-ringers redundant, so churches did not have to tolerate the behaviour of what he thought were unruly bell-ringers.

However, in reality, it required very rare expertise for one person to ring changes. The sound of a chime was a poor substitute for the rich sound of swinging bells, and the apparatus fell out of fashion. Consequently, the Ellacombe apparatus has been disconnected or removed from many towers in the UK. In towers where the apparatus remains intact, it is generally used like a Carillon, but to play simple tunes, or if expertise exists, to play changes.

Gamelan

Perhaps the best-known example from outside Europe of an organized system of bells is the gamelan, an Indonesian orchestra-like ensemble in which a prominent part is played by a variety of tuned bells, gongs, and metallophones.

Bell shape and tuning

The tuning of a bell is completely dependent on its shape. When first cast it is approximately correct, but it is then machined on a tuning lathe to remove metal until it is in tune. This is a very complex exercise which took centuries of empirical practice, and latterly modern acoustic science, to understand.

If a bell is part of a set to be rung or played together, then the initial dominant perceived sound, called the strike note, must be tuned to a designated note of a common scale. In addition each bell will emit harmonics, or partials, which must also be tuned so that these are not discordant with the bell's strike note. This is what Fuller-Maitland writing in Grove's dictionary of music and musicians meant when he said : "Good tone means that a bell must be in tune with itself."[9]

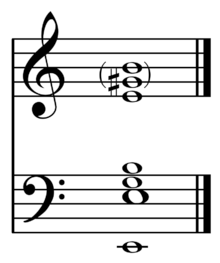

The principal partials are;

- hum note -an octave below the strike note,

- strike note

- tierce - minor third above the strike note

- quint - perfect fifth above the strike note

- nominal - octave above the strike note

Further, less dominant, partials include the major, third and perfect fifth in the octave above these.

"Whether a founder tunes the nominal or the strike note makes little difference, however, because the nominal is one of the main partials that determines the tuning of the strike note."[12] A heavy clapper brings out lower partials (clappers often being about 3% of a bell's mass), while a higher clapper velocity strengthens higher partials (0.4 m/s being moderate). The relative depth of the "bowl" or "cup" part of the bell also determines the number and strength of the partials in order to achieve a desired timbre.

Bells are generally around 80% copper and 20% tin (bell metal), with the tone varying according to material.

Tone and pitch is also affected by the method in which a bell is struck. Asian large bells are often bowl shaped but lack the lip and are often not free-swinging. Also note the special shape of Bianzhong bells, allowing two tones. The scaling or size of most bells to each other may be approximated by the equation for circular cylinders:

f=Ch/D2,

where h is thickness, D is diameter, and C is a constant determined by the material and the profile.[13]

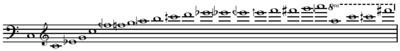

The major third bell

On the theory that pieces in major keys may better be accommodated, after many unsatisfactory attempts, in the 1980s, using computer modeling for assistance in design by scientists at the Technical University in Eindhoven, bells with a major-third profile were created by the Eijsbouts Bellfoundry in the Netherlands,[12] being described as resembling old Coke bottles[14] in that they have a bulge around the middle;[15] and in 1999 a design without the bulge was announced.[13]

See also

- Animation of English Full-circle ringing

- The ancient ringing system from Bologna, Italy.

- Handbell ringing - You can play methods or melodies on handbells

- Braid theory - the maths of Change ringing

- Video of tuning a bell

- Video explaining bell Tuning

- Veronese bellringing art from Verona, Italy.

Bell Organizations

The following organizations promote the study, music, collection and/or preservation and restoration of bells.[16] Nation(s) covered are given in parenthesis.

- The American Bell Association International (United States with foreign chapters)

- Association Campanaire Wallonne asbl (Belgium)

- Associazione Suonatori di Campane a Sistema Veronese (Italy)

- The Australian and New Zealand Association of Bellringers (Australia, New Zealand)

- Beratungsausschuss für das Deutsche Glockenwesen (Germany)

- British Carillon Society (United Kingdom)

- The Central Council of Church Bell Ringers (UK)

- Handbell Musicians of America (United States, chapter of English Handbell Ringers Association)

- Handbell Ringers of Great Britain (United Kingdom)

- Société Française de Campanologie (France)

- Verband Deutscher Glockengießereien e.V. (Germany)

- World Carillon Federation (multinational)

References

- ↑ From Glossary of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers 2016; "Campanology - Study of the history, art and science of making and ringing bells.

- ↑ From Glossary of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers 2016; " Campanologist - One who studies campanology, (popularly mis-used to refer to a ringer).

- ↑ "Jef Denyn Discography at Discogs". Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ↑ Bell Facts – Bell Chimes Archived 2006-08-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ East Bergholt and Constable Country: The Bell Cage, retrieved 27 September 2016

- ↑ Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers, Central Council of Church Bell Ringers, retrieved 27 September 2016

- ↑ County Lists from Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers, Central Council of Church Bell Ringers, retrieved 12 October 2015

- ↑ Musical Association (1902). Proceedings of the Musical Association, Volume 28, p.32. Whitehead & Miller, ltd.

- 1 2 John Alexander Fuller-Maitland (1910). Grove's dictionary of music and musicians, p.615. The Macmillan company. Strike note shown on C. Hemony appears to be the first to propose this tuning.

- ↑ Roads, Curtis, ed. (1992). Harvey Jonathan. "Moruos Plango, Vivos Voco: A Realization at IRCAM", The Music Machine, p.92. ISBN 978-0-262-68078-3. Harvey added, "a clearly audible, slow-decaying partial at 347 Hz with a beating component in it. It is a resultant of the various F harmonic series partials that can be clearly seen in the spectrum (5, [6], 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, etc.) beside the C-related partials."

- ↑ Downes, Michael (2009). Jonathan Harvey: Song offerings and White as jasmine, p.22. ISBN 978-0-7546-6022-4.

- 1 2 Neville Horner Fletcher, Thomas D. Rossing (1998). The Physics of Musical Instruments, p.685. ISBN 978-0-387-98374-5. Cites Schoofs et al., 1987 for major-third bell.

- 1 2 Rossing, Thomas D. (2000). Science of Percussion Instruments, p.139. ISBN 978-981-02-4158-2.

- ↑ http://www.cs.yale.edu/~douglas-craig/bells/Basic/what-is-a-carillon.pdf%5B%5D

- ↑ "Major third bell Archived 2007-10-18 at the Wayback Machine.", Andrelehr.nl.

- ↑ Rama, Jean-Pierre (1993). Cloches de France et d’ailleurs, Le Temps Apprivoisé, pp.229-230. Paris, France. ISBN 2283581583.

Bibliography

- The Ringing World

- Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers (Dove's guide for church bell ringers to the ringing bells of Britain and of the world (2000))

- Duckworth, Richard and Stedman, Fabian (1970) [1668] Tintinnalogia; or, The art of ringing, 1st ed. reprinted, Bath : Kingsmead Reprints, ISBN 0-901571-41-5

- Ingram, Tom (1954) Bells of England. London: F. Muller

- Stedman, F. (1990) [1677] Campanalogia : or The art of ringing improved ..., facsimile of 1st ed., Kettering : C. Groome, ISBN 1-85580-001-2

- Walters, H. B. (1908) Church Bells. London: Mowbray

- Wilson, Wilfrid G. (1965) Change Ringing: The Art and Science of Change Ringing on Church and Hand Bells. London: Faber

External links

- General

- Carillons

- The Carillon as a Musical Instrument, on the Web site of The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America (GCNA)

- Chimes

- Russian Orthodox bells

- British bells

- Discover Bell Ringing - an introduction for non-ringers

- Dove's Guide online

- Tintinnalogia, or, the Art of Ringing by Richard Duckworth, Fabian Stedman (1671), from Project Gutenberg

- Change Ringing Resources by Roger Bailey

- Central Council of Church Bell Ringers

- The Ringing World magazine

- Indian Bells

- Campanology in India: Bell Ringing, An Aid to Worship (in Hinduism) by S. Srikanta Sastri (1935)