Bell Witch

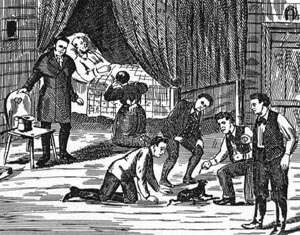

William Porter Attempts to Burn the Witch (Illus. 1894) | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Spirit |

| Similar creatures | Poltergeist, Jinn, Demon, Goblin |

| Mythology | American folklore |

| Other name(s) | Kate |

| Country | United States |

| Region | Middle Tennessee, Pennyroyal Plateau, Panola County, Mississippi |

| Habitat | Unknown, Cave |

The Bell Witch or Bell Witch Haunting is a legend from Southern folklore, centered on the 19th-century Bell family of Adams, Tennessee. John Bell Sr., who made his living as a farmer, resided with his family along the Red River in northwest Robertson County in an area currently within the town of Adams. According to legend, from 1817-1821, his family and the local area came under attack by an invisible entity subsequently described as a witch. The entity was able to speak, affect the physical environment and change forms. Some accounts record the spirit with the capability to be in more than one place at a time, cross distances with rapid speed and the power of prophecy.

In 1894, newspaper editor, Martin V. Ingram, published his Authenticated History of the Bell Witch. The book is widely regarded as the first full-length record of the legend and a primary source for subsequent treatments. The individuals recorded in the work were known historical personalities. In modern times, some skeptics have regarded Ingram's efforts as a work of historical fiction or even fraud, rather than a nascent folklore study or accurate reflection of belief in the region during the 19th century.

While not a fundamental element of the original recorded legend, the Bell Witch Cave in the 20th century became a source of continuing interest, belief, and generation of lore. Contemporary artistic interpretations such as in film and music have expanded the reach of the legend well beyond the regional confines of the Southern United States.

Synopsis

In his book An Authenticated History of the Bell Witch, author Martin Van Buren Ingram published that the poltergeist's name was Kate, after the entity claimed at one point to be "Old Kate Batts’ witch," and continued to respond favorably to the name.[1] The physical activity centered on the Bells' youngest daughter, Betsy, and her father, and 'Kate' expressed particular displeasure when Betsy became engaged to a local named Joshua Gardner.[2]

The haunting begins in late summer of 1817 with John Bell witnessing the apparition of a dog with the head of a rabbit. Bell fires at the animal but it disappears. Activity moved into the home with sounds of scratching, knocking and smacking lips with sheets being pulled from beds. The phenomenon grew in intensity as the entity pulled hair, slapped, pinched and stuck pins in the family with particular emphasis on Betsy.[3]

The Bells turned to a family friend James Johnston for help. After retiring for the evening at the Bell home, Johnston was awakened that night by the same phenomenon. That morning he told John Bell it was a "spirit, just like in the Bible." Soon word of the haunting spread with some traveling great distances to see the witch. The apparition began to speak out loud and have full conversations and even at one point repeating word for word two sermons given 13 miles apart at the same time.[4]

John Johnston, a son of James, devised a test for the witch, something no one outside his family would know, asking the entity what his Dutch step-grandmother in North Carolina would say to the slaves if she thought they did something wrong. The witch replied with his grandmother's accent, "Hut tut, what has happened now?" On another occasion, an Englishman stopped to visit and offered to investigate. On remarking on his family overseas, the witch suddenly began to mimic his English parents. Again at early morning, the witch woke him to voices of his parents worried as they had heard his voice as well. The Englishman quickly left that morning and later wrote to the Bell family the entity had visited his family in England and apologized for his skepticism.[5]

At times, the spirit displayed a form of kindness, especially towards Lucy, John Bell's wife, "the most perfect woman to walk to earth." The witch would give Lucy fresh fruit and sing hymns to her, and showed John Bell Jr. a measure of respect.[6]

Referring to John Bell Sr. as "Old Jack," the witch claimed she intended to kill him and signaled this intention through curses, threats and afflictions. The story climaxes with the Bell patriarch being poisoned by the witch. Afterward the entity interrupted the mourners by singing drinking songs.[7] In 1821, soon after Betsy called off her engagement, the entity told the family it was going to leave, but return in seven years in 1828. The witch returned on time to Lucy and her sons Richard and Joel with similar activities as before, but they chose not to encourage it, and the witch appeared to leave again.[8]

Several accounts say that during his military career, Andrew Jackson was intrigued with the story and his men were frightened away after traveling to investigate.[9] In an independent oral tradition recorded in the vicinity of Panola County, Mississippi, the witch was the ghost of an unpleasant overseer John Bell murdered in North Carolina. In this tradition, the spirit falls in love with the central character 'Mary' leading to her death, reminiscent of vampire lore.[10] The supernatural powers attributed to the Tennessee spirit have also been compared to that of jinn in mythology.[11]

In the manuscript attributed to Richard Williams Bell, he writes of the spirit:

Whether it was witchery, such as afflicted people in past centuries and the darker ages, whether some gifted fiend of hellish nature, practicing sorcery for selfish enjoyment, or some more modern science akin to that of mesmerism, or some hobgoblin native to the wilds of the country, or a disembodied soul shut out from heaven, or an evil spirit like those Paul drove out of the man into the swine, setting them mad; or a demon let loose from hell, I am unable to decide; nor has any one yet divined its nature or cause for appearing, and I trust this description of the monster in all forms and shapes, and of many tongues, will lead experts who may come with a wiser generation, to a correct conclusion and satisfactory explanation.[12]— Williams Bell, An Authenticated History of the Bell Witch: Chapter 8

Early written sources

The Saturday Evening Post

The newspaper Green Mountain Freeman of Vermont on Feb 7, 1856 republished a story regarding the Bell Witch legend and ascribed the story to the Saturday Evening Post. The Freeman was affiliated with the abolitionist Liberty Party.[13] The unidentified author described the apparition as the 'Tennessee Ghost' or 'Bell Ghost,' and stated the event occurred 30 years or more from the time the article was written. There are three human characters in the account, Mr. Bell, his daughter Betsey Bell, and Joshua Gardner. The author stated that the voice, which spoke freely about the house from all directions, would not manifest itself until the lights were extinguished at night. The phenomenon attracted wide interest. The author claimed to have become well acquainted with Mr. Gardner. When the ghost was asked how long it would remain, it replied, "until Joshua Gardner and Betsey Bell get married." The author goes on to state that Betsey Bell had fallen in love with Joshua Gardner and had discovered the skill of 'ventriloquism'. The author states that Ms. Bell then used her skill to attempt to convince Joshua Gardner to marry her. When they did not marry, the apparition disappeared.[14]

M. V. Ingram, in his An Authenticated History Of The Bell Witch, wrote that a Saturday Evening Post article regarding the Bell Witch had been retracted:

About 1849 the Saturday Evening Post, published either at Philadelphia or New York, printed a long sketch of the Bell Witch phenomenon, written by a reporter who made a strenuous effort in the details to connect her with the authorship of the demonstrations. Mrs. Powell was so outraged by the publication that she engaged a lawyer to institute suit for libel. The matter, however, was settled without litigation, the paper retracting the charges, explaining how this version of the story had gained credence, and the fact that at the time the demonstrations commenced Betsy Bell had scarcely advanced from the stage of childhood and was too young to have been capable of originating and practicing so great a deception. The fact also that after this report had gained circulation, she had submitted to any and every test that the wits of detectives could invent to prove the theory, and all the stratagems employed, served only to demonstrate her innocence and utter ignorance of the agency of the so-called witchery, and was herself the greatest sufferer from the affliction.[15]— Martin V. Ingram, An Authenticated History of the Bell Witch: Chapter 9

Murder of James Smith, 1868

In September 1868, an article was published entitled "Witchcraft and Murder: Hobgoblins and Old Gray Horses the Incentive to Crime." Tom Clinard and Dick Burgess were arrested for the murder of James Smith. It was reported that Smith claimed the powers of witchcraft while working near Adam's Station chopping wood on a farm with the defendants. The article stated Smith claimed to use these occult powers on Clinard and Burgess leading to the conflict.[16][17]

Ingram published an interview with Lucinda E. Rawls, of Clarksville, Tennessee, daughter of Alexander Gooch and Theny Thorn, both reported as close friends of Betsy Bell. Rawls testified that the Bell Witch was a frequent topic of conversation during her lifetime and pointed to a murder of a man for witchcraft as evidence for this claim.

The Bell Witch was, and is still, a great scapegoat. Every circumstance out of the regular order of things is attributed to the witch. It has not been long since a man claiming to be the witch was waylaid and murdered by two men who were cleared, on the plea that the murdered man had bewitched them.[18]— Lucinda Rawls, An Authenticated History of the Bell Witch: Chapter 12

Ingram appended a date of 1875 or 1876 to the bloodshed, but connected the Rawls recollection with the death of James Smith:

Smith came into the community a stranger, and was employed by Mr. Fletcher, where Clinard and Burgess were also engaged on the farm. Smith professed to be something of a wizard, or rather boasted of his power to hypnotize and lay spells on people, subjecting any one who came under his influence to his will, and it was reported that he claimed to have derived this power from the mantle of the Bell Witch. However, the writer interviewed Hon. John F. House, who was council for the defense, on the subject, who says that no such evidence was produced in the trial, but that the lawyers handled the Bell Witch affair for all that it was worth in the defense of their clients, presenting the analogy or similarity of circumstances with good effect on the jury.[18]— Martin V. Ingram, An Authenticated History of the Bell Witch: Chapter 12

Haunted House, 1880

On April 28, 1880 an article was published regarding a 'haunted house' in Springfield, Tennessee where knocking on the floor was heard. The author reported that several hundred people visited the home attempting to witness the phenomenon with many camped out over night despite the home owners asking them to leave. The author of the article took the opportunity to mention the Bell Witch legend:

It is an actual fact that several hundred intelligent people of Springfield and vicinity have been so excited over the noise as to go night after night to listen to it.... About thirty years ago Robertson county had a sensation similar to this known as the "Bell Witch," and people came from all parts of the country, even as far as New York, to hear or see her.[19]

The journal Studies in Philology, in 1919, published a study of witchcraft in North Carolina by folklorist Tom Peete Cross. Cross cites a column from the Nashville Banner where it mentions the paper had sent a reporter to Robertson County in the 1880s, John C. Cooke, to investigate reports of the possible reemergence of Bell Witch phenomenon.[20]

Nashville Centennial Exposition

Another account of the Bell Witch legend was reportedly published in 1880 as a part of a sketch of Robertson County written for Nashville's Centennial Exposition. The author of the article is unknown and the article is undated. Dates in the sketch end at 1880. In this account, the Bell entity did not explicitly poison John Bell.

At one time a vial of poison was found in the flue of the chimney, and being taken down, Dr. George B. Hopson gave one drop to a cat, causing its death in seven seconds. The witch claimed to have put the poison there for the purpose of killing Mr. Bell. Being asked how it was going to administer the poison, it said by pouring it into the dinner pot. It is remarkable that, although he enjoyed good health up to the time of this event, Mr. Bell died within [ ] days after the vial was found, being in a stupor at the time of his death. From this time the people visited the house less frequently, although the witch would now and then be heard.[21]

This is in contrast to the Ingram account, attributed to Richard Williams Bell, where John Bell was already suffering from an unknown affliction and bedridden for sometime. John Bell's son, John Bell Jr., found the vial in the cupboard after his father did not wake. The family called for Dr. Hopson, while the Bell Witch exclaimed she had fed the poison to John Bell. Alex Gunn and John Bell Jr. tested the poison on the cat with a straw, which "died very quick." John Bell died the next day on December 20, 1820.[12]

In the Centennial sketch, the entity described itself as one of seven spirits with three names given by the author: Three Waters, Tynaperty, and Black Dog.[21] The Ingram account also described a family of spirits. In addition to Kate, the other members of the 'family' had the names of Blackdog, Mathematics, Cypocryphy, and Jerusalem. Blackdog was described as the apparent leader of the group.[1]

Goodspeed's History of Tennessee

Goodspeed Brothers' 1886 History of Tennessee, published roughly 65 years after the initial purported events, recorded a short account of the legend. The paragraph does not mention Andrew Jackson or the elder Bell's death.

A remarkable occurrence, which attracted wide-spread interest, was connected with the family of John Bell, who settled near what is now Adams Station about 1804. So great was the excitement that people came from hundreds of miles around to witness the manifestations of what was popularly known as the "Bell Witch." This witch was supposed to be some spiritual being having the voice and attributes of a woman. It was invisible to the eye, yet it would hold conversation and even shake hands with certain individuals. The freaks it performed were wonderful, and seemingly designed to annoy the family. It would take the sugar from the bowls, spill the milk, take the quilts from the beds, slap and pinch the children, and then laugh at the discomfiture of its victims. At first it was supposed to be a good spirit, but its subsequent acts, together with the curses with which it supplemented its remarks, proved the contrary. A volume might be written concerning the performances of this wonderful being, as they are now described by contemporaries and their descendants. That all this actually occurred will not be disputed, nor will a rational explanation be attempted. It is merely introduced as an example of superstition, strong in the minds of all but a few in those times, and not yet wholly extinct.[22]

Accounts from 1890

An article was published February 3, 1890 describing a series of events from Adam's Station, Tennessee. At dusk, January 27, 1890, Mr. Hollaway reported watching two unknown women arrive at his home and dismount from their horses as he was feeding cattle. When he arrived at the house, the horses and women were gone. Mr. Hollaway's wife reported seeing the women in the yard as well. That week, Mr. Rowland attempted to place a sack of corn on his horse's back and it fell off. He again attempted to place the sack of corn on the horse's back several more times, but each time the sack fell off. Joe Johnson arrived and held on to the sack as Mr. Hollaway mounted his horse. They witnessed the sack floating away for 20 yards where it settled down at the fence. When the men went to retrieve the sack, a voice was heard, "You won't touch this sack anymore."[23]

A follow up report was published on February 18, 1890 with the title, "A Weird Witch: More Tales of a Mulhattanish Flavor from Adams Station." In the late 19th century, Joseph Mulhattan was a known hoaxer of newspaper articles.[24] The article was republished a few days later with the subtitle "More Tales of a Fishy Flavor." In the account, the entity was referred to only as the witch. The article reports that a Mr. Johnson was visiting Buck Smith and were discussing a recent visitation of the ghost at his home. They heard a knocking at the door, and when they opened the door, the knocking began at another door. They sat down and the dog began to fight with something invisible. Two minutes later, the door flew open and fire spread across the room blown by a cyclonic wind with the coals disappearing as they tried to put it out. That evening Mr. Johnson started home on his horse and something jumped on the back grabbing his shoulder as he tried to restrain the horse. He felt it jump off as he neared his home and move in the leaves into the woods.[25][26]

A Mr. Winters reported taking a peculiar bird while hunting with great difficulty. After he returned home, he opened the game-bag to discover the bird had disappeared and in place was a rabbit which then also disappeared. While burning vegetation outdoors, Mr. Rowland described a visit at 9 p.m. of a half clothed black man with one eye in his forehead that directed Mr. Rowland to follow him and dig at a large rock. The figure then disappeared. Mr. Rowland dug that night until exhaustion. He received help the next morning from Bill Burgess and Mr. Johnson and discovered something described as a "kettle turned bottom upward." They were unable to remove it as the soil began moving back into the hole. The report concludes saying that many people were visiting to see the witch.[25][26]

Martin Van Buren Ingram

Biography

Born near Guthrie, Kentucky, June 20, 1832, Martin Van Buren Ingram took over responsibility of the family farm at the age of 17. A member of Hawkins' Nashville Battalion during the Civil War, he was discharged for disability after the Battle of Shiloh.[27] Ingram began his editing and publishing career in April 1866 with the Robertson Register with no previous experience. October 1868, Ingram moved the paper to Clarksville and began issuing the Clarksville Tobacco Leaf in February 1869.[28] Ingram continued an association with the Leaf until about 1881. The consequences of poor health, family tragedy and fire limited his continuing interest in the newspaper industry.[29]

On the occasion of Ingram's death in October 1909, editor of the Clarksville Leaf Chronicle, W. W. Barksdale, wrote of his friend and colleague:

We doubt exceedingly if there ever lived a man who performed as much self-sacrificing labor to further the interests of the community in which he lived. He became a citizen of Clarksville forty years ago and from that time practically until the day of his death his greatest concern was the advancement and welfare of his adopted town and county.... A man of true mold, he despised all deceit, trickery, and littleness, and with a courage which nothing could daunt, he laid on the journalistic lash unsparingly whenever he thought the occasion required. Naturally, his was not a pathway strewn with roses – his was an aggressive nature, a fact which often brought him into serious collision with those with whom he took issue. Time, however, usually justified him in the positions which he assumed.[28]— W. W. Barksdale, Clarksville Leaf Chronicle

An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch

Ingram was reported, February 19, 1890, to have retired as editor from the Clarksville Chronicle.[30] Ingram subsequently traveled to Chicago in October 1893, while editor of the Progress-Democrat, to attempt to publish his An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch. The Wonder of the 19th Century, and Unexplained Phenomenon of the Christian Era. The Mysterious Talking Goblin that Terrorized the West End of Robertson County, Tennessee, Tormenting John Bell to His Death. The Story of Betsy Bell, Her Lover and the Haunting Sphinx.[31] In late March 1894, it was announced a publisher, W. P. Titus, in Clarksville would print the work and it was released a few months later.[32][33] In the introduction to the book, Ingram published a letter dated July 1, 1891 from former TN State Representative James Allen Bell of Adairville, Kentucky.

J. A. Bell, a son of Richard Williams Bell and a grandson of John Bell, Sr., explained that his father had met with his brother John Bell Jr. before his death and they agreed no material he had collected should be released until the last immediate family member of John Bell Sr. had died. The last immediate member of the family and youngest child of John Bell Sr., Joel Egbert Bell died in 1890 at the age of 77.[34]

Now, nearly seventy-five years having elapsed, the old members of the family who suffered the torments having all passed away, and the witch story still continues to be discussed as widely as the family name is known, under misconception of the facts, I have concluded that in justice to the memory of an honored ancestry, and to the public also whose minds have been abused in regard to the matter, it would be well to give the whole story to the World.[35]— J. A. Bell, 1891 Letter, An Authenticated History of the Bell Witch

J. A. Bell expressed the belief that his father's manuscript was written when he was 35 years old in 1846. He claimed his father gave him the manuscript and family notes shortly before his death in 1857. Richard Williams Bell was roughly 6 to 10 years of age during the initial manifestations of the Bell Witch phenomenon and 17 at the occurrence of the spirit's return in 1828. The reported contributions of Richard Williams Bell, approximately 90 pages in length, are recorded in Chapter 8 of Ingram's work, entitled Our Family Trouble.[36]

According to Brian Dunning no one has ever seen this diary, and there is no evidence that it ever existed: "Conveniently, every person with firsthand knowledge of the Bell Witch hauntings was already dead when Ingram started his book; in fact, every person with secondhand knowledge was even dead." Dunning also concluded that Ingram was guilty of falsifying another statement, that the Saturday Evening Post had published a story in 1849 accusing the Bells' daughter Elizabeth of creating the witch, an article which was not found at the time.[37] Joe Nickell argues the chapter includes the use of Masonic themes and anachronism which impacts credibility.[38] Jim Brooks, native of Adams, writes in his work Bell Witch Stories You Never Heard, that Bell family descendants report that Ingram did not return the manuscript to the family. Brooks explores the possibility that Ingram would have had an enhanced opportunity to modify the story by not returning the papers.[39]

The account of General Andrew Jackson's visit is confined to Chapter 11 of Ingram's work. The chapter is a letter from Col. Thomas L. Yancey, an attorney in Clarksville, dated January 1894. Yancey relates that his grandfather, Whitmel Fort, was a witness to phenomena at the Bell homestead and had related the story of Jackson's visit which was undated in the letter.[40]

Paranormal investigator Benjamin Radford, as well as Brian Dunning, conclude that there is no evidence that Andrew Jackson visited the Bell family home. During the years in question, Jackson's movements were well documented, and nowhere in history or his writings is there evidence of his knowledge of the Bell family. According to Dunning, "The 1824 Presidential election was notoriously malicious, and it seems hard to believe that his opponent would have overlooked the opportunity to drag him through the mud for having lost a fight to a witch."[37][41]

Keith Cartwright of the University of North Florida compares Ingram's work with Uncle Remus folklore as recorded by Joel Chandler Harris and also as an expression of the psychological shame of slavery and Native American removal. The slaves in the account are regarded as experts on the witch, with Uncle Zeke identifying the witch as, "dat Injun spirit...the Injuns was here fust, and we white fokes driv em out, all but dem whar wur dead and cudent go, an da's here yit, in der spirit." The figure of "progress" Gen. Andrew Jackson was brought nearly to heel and the master, John Bell, was dead. The role of the trickster not played by the Br'er Rabbit but the witch-rabbit, the spirit's common animal form. The displaced, blacks, widows and girls, act as witness to a force polite society cannot comprehend. The witch, "appears as a catch-all for every remainder of resistant agency."[42]

Events in the 20th Century

A prophecy was reported in 1903 that the witch could return on the centennial of the Bell family arrival in Tennessee.[43] By September, a local paper was incredulous as she was not reported to have returned in August.[44]

Charles Bailey Bell, a grandson of John Bell Jr., and neurologist in Nashville, published a book entitled The Bell Witch: A Mysterious Spirit in 1934. In the work, he recounted stories told to him by his great aunt Betsy later in her life. This included another account of Andrew Jackson's visit and of a boy trapped in the Bell Witch Cave and pulled out of the cave feet first by the witch. Bell also detailed a purported series of prophecies given to his ancestors in 1828 by the spirit, including the claim the witch was set to return in 1935, 107 years after her last visit to the Bell family.[45]

In 1937, there were reports of quirky events. Louis Garrison, owner of the farm that included the Bell Witch Cave, heard unexplained noises coming from inside. Bell descendants described the sound of something rubbing against a house, a paper like object that flew out the door and reentered through a side door, and faint music heard from a piano.[46] A group from the local Epworth League were reported to have attended a wiener roast in a rock quarry near the Bell Witch Cave on July 29, 1937. The group were joking about the legend when they saw a figure of a woman sitting on top of the cliff over the cave causing many to flee.[47] According to the newspaper, a minister in the group later claimed to have investigated and discovered it was moon light on a rock. The second report concluded with a weather report that the moon was barely noticeable that night.[48] Jim Brooks published in 2015 that his mother was in attendance at the roast, and relates that the minister caught up to the youth on the road to town after discovering no explanation for the figure. [49]

In November 1965, an article was published involving an antique oak rocking chair said to have been previously owned by attorney Charlie Willett, a Bell descendant. The rocking chair was recently sold in an estate sale to Mrs. J. C. Adams, owner of an antique store on U.S. 41. A customer sat down in the chair, after learning it was not for sale, and while rocking in the chair asked Mrs. Adams if she believed in the supernatural. Two weeks later, the customer's daughter visited the home of Mrs. Adams and said after her mother had left and visited the Bell cemetery a voice told her to "stand up and look around, you will find something of much value." After some car trouble, the woman walked out into a field and found a black iron kettle turned over. She turned the kettle over and found a pearl buckle in the grass. The woman's daughter reported a jeweler estimated the buckle to be 160 to 200 years old.[50]

Bonnie Haneline, in 1977, recounted a time during her childhood in 1944 when she was exploring the cave. She left English class, playing 'hooky,' and borrowed a lantern from Mrs. Garrison, the cave owner. She reported to have explored the cave with her friends for several years. While she was inside, her lantern blew out despite no breeze inside the cave. She managed to relight the lantern and it blew out again. Terrified, she crawled along the water path of the cave in the dark until she reached the entrance where she saw an opened can of pork and beans and marshmallows. Later that evening, she learned law enforcement discovered two escaped fugitives in the back of the cave. She credited the witch with helping her avoid them.[51]

A visit in 1977 was reported of a group five soldiers from nearby Fort Campbell to the Bell Witch Cave. One of the soldiers was sitting on a rock and expressed skepticism of the legend when something invisible grabbed him around the chest.[52]

In 1986, staff writer David Jarrard for The Tennessean and photographer Bill Wilson, the latter also a member of the National Speleological Society, were given permission to sleep in the cave over night. While in the first cave room they heard a noise from deeper in the cave Jarrard estimated at 30 yards. Subsequently, an "unwavering groan" repeated again with greater volume and accompanied by several loud thumps. When it began a third time, the men retreated to the gate entrance. They explored the wiring to the lights looking for a reason for the noises. They went back to the first cave room but heard a rumble near the entrance. Walking back to the entrance they discovered the rumble was noise from a jet. As they reached the gate, a loud, high pitched scream emanated from inside the cave. The journalists left and did not spend the night.[53]

In 1987, H. C. Sanders, owner of a nearby gas station, reported 20 years earlier he ran out of gas at night near the Red River across from the Bell Witch Cave. He began to walk towards town when a rabbit came out of the woods and began to follow him. Sanders walked faster, but the rabbit kept pace even as he broke out into a run. After a mile, Sanders sat down on a log to catch his breath. The rabbit hopped up on the other side of the log looked at him and said, "Hell of a race we had there, wasn't it?"[54]

Skeptical Evaluation

According to Radford, the Bell Witch story is an important one for all paranormal researchers: "It shows how easily legend and myth can be mistaken for fact and real events and how easily the lines are blurred" when sources are not checked.[41] Dunning wrote that there was no need to discuss the supposed paranormal activity until there was evidence that the story was true. "Vague stories indicate that there was a witch in the area. All the significant facts of the story have been falsified, and the others come from a source of dubious credibility. Since no reliable documentation of any actual events exists, there is nothing worth looking into."[37]

Dunning concludes, "I chalk up the Bell Witch as nothing more than one of many unsubstantiated folk legends, vastly embellished and popularized by an opportunistic author of historical fiction."[37] Radford reminds readers that "the burden of proof is not on skeptics to disprove anything but rather for the proponents to prove... claims".[41]

Joe Nickell has written that many of those who knew Betsy suspected her of fraud and the Bell Witch story "sounds suspiciously like an example of “the poltergeist-faking syndrome” in which someone, typically a child, causes the mischief."[38]

Bell Witch in culture

Film

There have been several movies based, at least in part, on the Bell Witch legend, including The Blair Witch Project in 1999, Bell Witch Haunting in 2004, An American Haunting in 2005, Bell Witch: The Movie in 2007, and The Bell Witch Haunting in 2013.

Television

The American television series Ghost Adventures filmed an episode at the Bell Witch Cave.[55]

An American television series – Cursed: The Bell Witch – based on the latest members of the Bell family trying to end the curse. It premiered October 2015 on the A&E Network.[56]

Music and Theater

Charles Faulkner Bryan, as apart of a Guggenheim Fellowship, composed The Bell Witch, a cantata which premiered in Carnegie Hall in 1947 with Robert Shaw conducting the Juilliard Chorus and Orchestra.[57]

Nashville music group The Shakers released Living In The Shadow Of A Spirit in 1988 on vinyl record EP.[58]

Ann Marie DeAngelo and Conni Ellisor choreographed and composed a ballet entitled The Bell Witch for the Nashville Ballet.[59]

Nashville Children's Theatre premiered Our Family Trouble: The Legend of the Bell Witch in 1976. The play was written by Audrey Campbell.[60]

A play by Ric White, The Bell Witch Story. First performed in 1998 by the Sumner County Players.[61] And performed again in 2008 by the Tennessee Theater Company.[62]

A play by David Alford, Spirit: The Authentic Story of the Bell Witch of Tennessee, performed in Adams, TN during the Bell Witch Fall Festival in late October.[63]

The Danish metal band Mercyful Fate released a song titled "The Bell Witch" on their 1993 album In the Shadows.[64]

Seattle-based doom metal band Bell Witch took their name from this legend.[65]

Merle Kilgore recorded a song titled "The Bell Witch" in 1964.[66]

Madeline recorded a song titled "The Legend of the Bell Witch" in 2014.[67]

Selected Bibliography

| Year | Title | Author | Publisher | ASIN/ISBN | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1894 | An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch | Ingram, Martin V. | W. P. Titus (1894); Rare Book Reprints (1961) | Variable by reprint | First known full length account. |

| 1930 | The Bell Witch of Tennessee | Miller, Harriet Parks | Leaf-Chronicle Publishing | Local historian from Port Royal, Tennessee.[68] | |

| 1934 | The Bell Witch: A Mysterious Spirit | Bell, Charles Bailey | Lark Bindery | B000887W6Y | Author a descendant of the Bell family.[69] |

| 1969 | The Bell Witch at Adams | Barr, Gladys | David Hutchinson Publishing | B003ZFNLS0 | Children's Literature.[70] |

| 1979 | Echoes of the Bell Witch in the Twentieth Century | Brehm, H. C. | Brehm, H. C. | B0006EKRKS | Eden family anecdotes (Bell Witch Cave).[71] |

| 1994 | Infamous Bell Witch of Tennessee | Price, Charles Edwin | Overmountain Press | 1570720088 | |

| 1997 | The Bell Witch: An American Haunting | Monahan, Brent | St. Martin's Press | 031215061X | Novel. Basis for the 2005 film, An American Haunting.[72] |

| 1999 | Season of the Witch | Taylor, Troy | Whitechapel Productions | 1892523051 | |

| 2000 | The Bell Witch: The Full Account | Fitzhugh, Pat | Armand Press | 097051560X | |

| 2002 | All That Lives: A Novel of the Bell Witch | Sanders-Self, Melissa | Warner Books | 0446526916 | Novel.[73] |

| 2008 | Bell Witch: The Truth Exposed | Headley, Camille Moffitt | Bell Witch Truth | 0615222617 | With Kirby family (Bell Witch Cave).[74] |

| 2008 | The Bell Witch Anthology | Moretti, Nick | BookSurge Publishing | 1419676636 | |

| 2008 | The Bell Witch Unveiled at Last!: The True Story of a Poltergeist | Lyons, D. J. | PublishAmerica | 1604744774 | |

| 2013 | The Bell Witch | Taff, John F. D. | Books of the Dead | 1927112192 | Novel. |

| 2014 | The Secrets of the Bell Witch | Hockenheimer, Jeff | Xlibris | 1493159518 | |

| 2015 | Bell Witch Stories You Never Heard | Brooks, Jim | McClanahan Publishing House | 1934898546 | Native of Adams, Tennessee. Descendant of John Johnston.[75] |

| 2015 | Little Sister Death | Gay, William | Dzanc Books | 1938103130 | Novel. Tennessee Author. Published posthumously.[76] |

| 2016 | Our Family Trouble: A Domestic Thriller | Winston, Don | Tigerfish | 0692838082 | Novel. Author Nashville native.[77] |

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Ingram, Martin (19 March 2003). "An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch: Chapter 8, Part 3". Bell Witch Folklore Center. Phil Norfleet. Archived from the original on 19 March 2003. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ Christopher R. Fee; Jeffrey B. Webb (31 August 2016). American Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales: An Encyclopedia of American Folklore (3 Volumes). ABC-CLIO. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-1-61069-568-8.

- ↑ Alan Brown (26 February 2009). Haunted Tennessee: Ghosts and Strange Phenomena of the Volunteer State. Stackpole Books. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-8117-4648-9.

- ↑ Mark Moran; Mark Sceurman (1 May 2009). Weird U.S.: Your Travel Guide to America's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 254–55. ISBN 978-1-4027-6688-6.

- ↑ Pat Fitzhugh (1 October 2000). The Bell Witch: The Full Account. The Armand Press. pp. 57, 65. ISBN 978-0-9705156-0-5.

- ↑ Charles Edwin Price (January 1994). The Infamous Bell Witch of Tennessee. The Overmountain Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-1-57072-008-6.

- ↑ "TSLA::"Tennessee Myths and Legends"". share.tn.gov. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ McClure's Magazine. S.S. McClure, Limited. 1922. pp. 114–.

- ↑ McCormick, James; Macy Wyatt (2009). Ghosts of the Bluegrass. University Press of Kentucky. p. 94.

- ↑ Hudson, Arthur Palmer; Pete Kyle McCarter (January–March 1934). The Bell Witch of Tennessee and Mississippi: A folk legend. The Journal of American Forklore. pp. 45–63.

- ↑ Rosemary Ellen Guiley; Philip J. Imbrogno (8 July 2011). The Vengeful Djinn: Unveiling the Hidden Agenda of Genies. Llewellyn Worldwide. pp. 101–05. ISBN 978-0-7387-2881-0.

- 1 2 Ingram, Martin (17 January 2003). "An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch:Chapter 8, Part 6". Bell Witch Folklore Center. Phil Norfleet. Archived from the original on 17 January 2003. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ Abby Maria Hemenway (1882). The History of the Town of Montpelier, Including that of the Town of East Montpelier, for the First One Hundred and Two Years... Miss A. M. Hemenway. p. 312.

- ↑ "The Tennessee Ghost". Green Mountain Freeman (Volume 13, Number 7). February 7, 1856. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Ingram, Martin (10 March 2003). "An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch: Chapter 9". Bell Witch Folklore Center. Phil Norfleet. Archived from the original on 10 March 2003. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ "Witchcraft and Murder: Hobgoblins and Old Gray Horses the Incentive to Crime". The Courier-Journal. September 21, 1868. p. 1. Retrieved November 30, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Clinard-Burgess". Nashville Union and American. March 20, 1869. p. 4. Retrieved November 30, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Ingram, Martin (7 March 2003). "An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch: Chapter 12". Bell Witch Folklore Center. Phil Norfleet. Archived from the original on 7 March 2003. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ "Springfield's Ghost". The Daily American. April 28, 1880. p. 1. Retrieved November 28, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Tom Peete Cross (1919). Studies in Philology. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 240–.

- 1 2 Duggan, W. L. (1 January 1900). "Sketches of Sevier and Robertson Counties". The American Historical Magazine. 5 (4): 310–25. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ Goodspeed's History of Tennessee: The History of Robertson County. Nashville TN: The Goodspeed Publishing Co. 1886. p. 828. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ "A Rural Fake: A Mulhattanism from Adam's Station Creating Some Excitement". The Daily American. February 3, 1890. p. 2. Retrieved June 28, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hoaxes of Joseph Mulhattan". Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- 1 2 "A Weird Witch: More Tales of a Fishy Flavor from Adam's Station, TN". The Courier-Journal. February 21, 1890. p. 6. Retrieved November 28, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "A Weird Witch: More Tales of a Mulhattanish Flavor from Adams Station". The Daily American. February 18, 1890. p. 2. Retrieved November 28, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Drop Stitches". The Nashville Tennessean (Vol. 16, No. 41). July 20, 1924.

- 1 2 "Martin Van Buren Ingram". Bell Witch Folklore Center. Phil Norfleet. 29 October 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ "Veteran Journalist Dies in Clarksville". The Tennessean. October 6, 1909. p. 9. Retrieved December 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Clarksville Retirement". The Daily American. February 19, 1890. p. 4. Retrieved November 29, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "A Clarksville Author". The Daily American. October 29, 1893. p. 10. Retrieved November 29, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "A "Witch" Story". The Daily American. March 31, 1894. p. 5. Retrieved November 29, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "A Bell Witch". Hopkinsville Kentuckian. July 3, 1894. p. 2. Retrieved November 29, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Jeff Hockenheimer (3 February 2014). The Secrets of the Bell Witch. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-1-4931-5952-9.

- ↑ Ingram, Martin (3 March 2003). "An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch: Chapter 1". The Bell Witch Folklore Center. Phil Norfleet. Archived from the original on 3 March 2003. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Ingram, Martin (10 March 2003). "An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch: Chapter 8, Our Family Trouble". Bell Witch Folklore Center. Phil Norfleet. Archived from the original on 10 March 2003. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Dunning, Brian. "Skeptoid #118: Demystifying the Bell Witch". Skeptoid. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- 1 2 Nickell, Joe. "The ‘Bell Witch’ Poltergeist". Skeptical Inquirer. Center for Inquiry. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Brooks, Jim (2015). Bell Witch Stories You Never Heard. McClanahan Publishing House. p. 80. ISBN 1934898546.

- ↑ Ingram, Martin (3 October 2002). "An Authenticated History of the Famous Bell Witch: Chapter 11". Bell Witch Folklore Center. Phil Norfleet. Archived from the original on 3 October 2002. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Radford, Benjamin (January–February 2012). "The Bell Witch Mystery". Skeptical Inquirer Magazine. 36 (1): 32–33.

- ↑ Cartwright, Keith (5 January 2016). "Jackson's Villes, Squares, and Frontiers of Democracy". In Fred Hobson, Barbara Ladd. The Oxford Handbook of the Literature of the U.S. South. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-19-045511-8. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ↑ "Will Tennessee's Terrible "Bell Witch" Keep It's promise". The Cincinnati Enquirer (Volume 9, Number 130). May 10, 1903.

- ↑ "Report from Springfield Herald". Hopkinsville Kentuckian (Volume 25, Number 73). September 15, 1903.

- ↑ Burns, Charles (September 29, 1935). "Famed 'Ghost' Due Back in '35 After 107 Year Absence". The Des Moines Register (Volume 87, Number 100).

- ↑ Tucker, Jack (August 1, 1937). "Something Goes on at Adams; It May Be Kate, the Bell Witch". The Tennessean (Volume 32, Number 154).

- ↑ Tucker, Jack (August 4, 1937). "Form Lately Appears on Cliff Overlooking Bell Witch Cave". The Tennessean (Volume 82, Number 159).

- ↑ "Minister's Probe Reveals Rock Leaguers Mistook for Old Kate". The Tennessean (Volume 32, Number 163). August 6, 1937.

- ↑ Brooks, Jim (2015). Bell Witch Stories You Never Heard. McClanahan Publishing House. p. 182. ISBN 1934898546.

- ↑ Preston, Bill (November 28, 1965). "Has Bell Witch Returned Home?". The Tennessean (Volume 60, Number 211).

- ↑ McCampbell, Candy (October 30, 1977). "Is the Bell Witch a Mean Spirit?". The Tennessean (Volume 72, Number 205).

- ↑ Wick, Don (October 26, 1986). "Witch bothers, bewilders". The Clarion-Ledger (Volume 33, Number 109).

- ↑ Jarrard, David (October 27, 1986). "Bell Witch Cave too much 'story' for brave staffers". The Tennessean (Volume 81, Number 222).

- ↑ Maines, John (October 27, 1987). "Thar's gold in them thar witch's chills". The Clarion-Ledger (Volume 151, Number 180).

- ↑ "Investigate Bell Witch Cave With Ghost Adventures". Travel Channel. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Young, Nicole (October 20, 2015). "A&E examines history behind Tennessee's Bell Witch". USA Today. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Livingston, Carolyn (1 January 1990). "Charles Faulkner Bryan and American Folk Music". The Bulletin of Historical Research in Music Education. 11 (2): 76–92. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Shakers – Living In The Shadow Of A Spirit". Discogs. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Staff. "Nashville Ballet presents ‘Bell Witch’ love story". The City Paper. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Hieronymous, Clara (October 31, 1976). "Bell Witch Legend: Spooky But True". The Tennessean (Volume 71, Number 206).

- ↑ Peebles, Jennifer (October 11, 1998). "Witch Story a Bell wringer". The Tennessean.

- ↑ "Halloween Happenings". The Tennessean. October 30, 2008.

- ↑ Herndon, Carleen (October 26, 2016). "Bell Witch back in town". The Tennessean. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ "Mercyful Fate – In the Shadows". Encyclopaedia Metallum.

- ↑ Davis, Cody (18 May 2016). "Former BELL WITCH Drummer/Vocalist, Adrian Guerra, Passes Away – Metal Injection". Metal Injection. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ "Merle Kilgore – The Bell Witch". 45cat. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ "Madeline Live at Caledonia Lounge on 2014-11-22". Internet Archive. Sloan Simpson. 22 November 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ "'Bell Witch' Author Dies at Port Royal". The Tennessean (Volume 29, Number 428). February 4, 1935.

- ↑ "Promised Return of Bell Witch Recalls Sensational Stories". The Tennessean (Volume 29, Number 532). April 1, 1935.

- ↑ "Christ the King Salutes Children's Book Week". The Tennessean (Volume 63, Number 208). November 21, 1968.

- ↑ Walker, Hugh (April 22, 1979). "The Bell Witch Strikes Again". The Tennessean (Volume 74, Number 14).

- ↑ Germain, David (May 4, 2006). "Haunting Creepy But Too Noisy". The Anniston Star.

- ↑ Watson, Chris (June 16, 2002). "Witch Legend Makes for Gripping Story". Santa Cruz Sentinel.

- ↑ "20th Annual Festival of Books". The Tennessean. October 9, 2008.

- ↑ "Dr. James Brooks to Reveal Never-Before-Told Bell Witch Stories". Westview (The Nashville Ledger) (Volume 31, Number 35). August 8, 2007.

- ↑ Akbar, Arifa (1 October 2015). "Little Sister Death by William Gay, book review: Writer's deal with the devil". The Independent. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Cartwright, Keith Ryan. "Bell Witch legend meets modern day Nashville in new thriller". The Tennessean. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bell Witch. |

- Tennessee Myths and Legends: Bell Witch Tennessee State Library and Archives Exhibition.

- The Bell Witch of Tennessee A MonsterTalk episode on The Bell Witch.

- The Bell Witch by researcher Pat Fitzhugh.

- The Historic Bell Witch Cave

- Prairie Ghosts – The Bell Witch Cave

- Episode Eighteen: The One about the Bell Witch Encounters podcast featuring Dr. Brandon Barker, Visiting Lecturer in Folkloristics at Indiana University Bloomington.

- "A Witch As Was A Witch" Article by Irvin S. Cobb for McClure's, published in 1922. Includes a family anecdote that his great grandfather witnessed the haunting and was convinced of the legitimacy.

- The Bell Witch, a WSM Tall Tales radio broadcast October 6, 1953.

- Bell Witch Fall Festival Destination site for the annual Robertson County theater events organized by the non-profit Community Spirit, Inc.