Belgorod-Kharkov Offensive Operation

| Belgorod-Kharkov Offensive Operation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200,000 men; 237 tanks and assault guns at the outset |

1,144,000 men[1] 2,418 tanks[2] 13,633 guns and rocket launchers[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

10,000 men killed or missing in action, 20,000 WIA[3] 240 tanks lost[3] unknown guns |

71,611 killed 183,955 wounded[4] 1864 tanks lost[5] 423 artillery guns[5] 153 aircraft[5] | ||||||

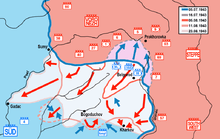

The Belgorod-Kharkov Strategic Offensive Operation, or simply Belgorod-Kharkov Offensive Operation, and also known as the Fourth Battle of Kharkov, was a Soviet strategic summer offensive that aimed to recapture Belgorod and Kharkov (now Kharkiv)a , and destroy the German forces of the 4th Panzer Army and Army Detachment Kempf. The operation was codenamed Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev (Russian: Полководец Румянцев), after the 18th-century Field Marshal Peter Rumyantsev and was conducted by the Voronezh and Steppe Fronts in the southern sector of the Kursk Bulge.

The operation began in the early hours of 3 August 1943, with the objective of following up the successful Soviet defensive effort against the German Operation Citadel. The offensive was directed against the German Army Group South's northern flank. By 23 August, the troops of the Voronezh and Steppe Fronts had successfully seized Kharkov from German forces. It was the last time that Kharkov changed hands during the Soviet-German War. The operation led to the retreat of the German forces in Ukraine[6] behind the Dnepr River, and it set the stage for the Battle of Kiev in autumn 1943.

Background

Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev had been planned by Stavka to be the major Soviet summer offensive in 1943. However, due to heavy losses sustained during the Battle of Kursk in July, time was needed for the Soviet formations to recover and regroup. Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev commenced on 3 August, with the aim of the defeating the 4th Panzer Army, Army Group Kempf, and the southern wing of Army Group South. It was also hoped that the German 1st Panzer Army and the newly reformed 6th Army would be trapped by an advance of the Red Army forces to the Black Sea.[7]

The Soviet forces included the Voronezh Front and the Steppe Front, which deployed about 1,144,000 men[1] with 2,418 tanks[2] and 13,633 guns and rocket launchers[2] for the attack. Against this the German army could field 200 000 men and 237 tanks and assault guns.

German Army Group South commander General Erich von Manstein had anticipated that the Soviets would launch an attack across the Dnieper and Mius Rivers in an attempt to reach the Black Sea, cutting off the German forces extended in the southern portion of Army Group South in a repeat of the Stalingrad disaster.[8] When the Soviet Southern Front and the Southwestern Front launched just such an attack on 17 July the Germans responded by moving the II SS Panzer Corps, XXIV Corps and XLVIII Panzer Corps southward to blunt the Soviet offensive. In fact these Soviet operations were intended to draw off German forces from the main thrust of the Soviet offensive, to dissipate the German reserve in anticipation for their main drive.[9]

The Soviet plan called for the 5th and 6th Guards Armies, and the 53rd Army, to attack on a 30-kilometer wide sector, supported by a heavy artillery concentration, and break through the five successive German defensive lines between Kursk and Kharkov. The former two armies had borne the brunt of the German attack in Operation Citadel. Supported by two additional mobile corps, the 1st Tank Army and the 5th Guards Tank Army, both mostly reequipped after the end of Operation Citadel, would act as the front's mobile groups and develop the breakthrough by encircling Kharkov from the north and west. Mikhail Katukov's 1st Tank Army was to form the westward-facing outer encirclement line, while Pavel Rotmistrov's 5th Guards Tank Army would form the inner line, facing the city. A secondary attack to the west of the main breakthrough was to be conducted by the 27th and 40th Armies with the support of four separate tank corps. Meanwhile, to the east and southeast, the 69th and 7th Guards Armies, followed later by the Southwestern Front's 57th Army, were to join the attack.[10]

Offensive Operation

On 3 August the offensive was begun with a heavy artillery barrage directed against the German defensive positions. Though the German defenders fought tenaciously, the two tank armies committed to the battle could not be held back. By 5 August the Soviets had broken through the German defensive lines, moving into the rear areas and capturing Belgorod while advancing some 60 km. Delivering powerful sledgehammer blows from the north and east, the attackers overwhelmed the German defenders.[11]

German reserves were shifted from the Orel sector and north from the Donbas regions in an attempt to stem the tide and slow down the Soviet attacks. Success was limited to the "Grossdeutschland" division delaying the 40th Army by a day. Seven panzer and motorized divisions making up the III Panzer Corps, along with four infantry divisions were assembled to counterattack into the flank of the advancing Soviet forces, but were checked. After nine days the 2nd SS "Das Reich" and 3rd SS "Totenkopf" divisions arrived and initiated a counterattack against the two Soviet Armies near Bogodukhov, 30 km northwest of Kharkov. In the following armoured battles of firepower and maneuver the SS divisions destroyed a great many Soviet tanks. To assist the 6th Guards Army and the 1st Tank Army, the 5th Guards Tank Army joined the battles. All three Soviet armies suffered heavily, and the tank armies lost more than 800 of their initial 1,112 tanks.[12][13] These Soviet reinforcements stopped the German counterattack, but their further offensive plans were blunted.[13]

With the Soviet advance around Bogodukhov stopped, the Germans now began to attempt to close the gap between Akhtyrka and Krasnokutsk. The counterattack started on 18 August, and on 20 August "Totenkopf" and "Großdeutschland" met behind the Soviet units.[12] Parts of two Soviet armies and two tank corps were trapped, but the trapped units heavily outnumbered the German units. Many Soviet units were able to break out, while suffering heavy casualties.[12][14] After this setback the Soviet troops focused on Kharkov and captured it after heavy fighting on 23 August.

The battle is usually referred to as the Fourth Battle of Kharkov by the Germans and the Belgorod–Kharkov Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviets.[15][16] The Soviet operation was executed in two primary axis, one in the Belgorod-Kharkov axis and another in the Belgorod-Bogodukhov axis.[16]

On the first day, the units of the Voronezh Front quickly penetrated the German front-line defences on the boundary of the 4th Panzer Army and Army Group "Kempf", between Tomarovka and Belgorod and gained 100 kilometres in a sector along the Akhtyrka-Bogodukhov-Olshany-Zolochev line along the banks of the Merla river. They were finally halted on 12 August by armoured units of the III Panzer Corps. On 5 August 1943 XI Corps evacuated the city of Belgorod. (see Belgorod-Bogodukhov Offensive Operation) [17]

Following its withdrawal from Belgorod on the night of 5/6 August 1943 the XI Army Corps under the command of (Raus) now held defensive positions south of the city between the Donets & Lopan Rivers north of Kharkov. The XI Army Corps consisted of a Kampfgruppe from the 167th Infantry Division, the 168th, 106th, 198th, 320th Infantry Divisions, and the 6th Panzer Division which acted as was the corps reserve.[18]b This constituted a deep salient east into Soviet lines and was subject to outflanking attempts on the corps left flank, indeed Soviet armoured units had already appeared 20 miles behind the corps front line. XI Army Corps now made a series of phased withdrawals toward Kharkov to prevent encirclement.

Only reaching the final defenses north of the city on 12 August 1943, following breakthroughs by the 57th & 69th Armies in several sectors of the front-line, the disintegration of the 168th Infantry Division and after an intervention by the corps reserve.[17] When its attempts to force a breakthrough in the Bogodukhov-Olshany-Zolochev met with frustration along the Merla River, the Steppe Front directed its assaults towards Korotich, a sector held by 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich to cut the Poltava-Kharkov rail link. Fierce fighting ensued, in which Korotich was captured by the 5th Guards Mechanised Corps and subsequently recaptured by grenadiers from 2nd SS then to remain under German control, but the 5th Guards Tank Army (Pavel Rotmistrov) did cut the rail link finally on 22 August 1943.[19]

The loss of this vital line of communication; while not fatal in itself, was a serious blow to the ability of Army Group Kempf, to defend the city from the constant Red Army attacks. This meant critical delays of supplies and reinforcements, and the unit's position was becoming increasingly untenable. The way to Poltava now remained open, but Vatutin hesitated to push through while the Germans flanking the gap held firm. Instead, he turned his left flank armies; the 5th Guards Tank Army and the 5th Guards Army, against the western front of Army Group Kempf where the 2nd and 3rd SS Panzer Divisions fought to keep the front angled south westward away from Kharkov.

On the weaker east front of Army Group Kempf, the Soviet 57th Army cleared the right bank of the Donets between Chuguyev & Zmiyev, but the army command somehow could not quite bring itself to try for a full scale breakthrough.[20]

These threats had led to a request by General Werner Kempf to abandon the city on 12 August 1943. Erich von Manstein did not object, but Adolf Hitler countered with an order that the city had to be held "under all circumstances".c After a prediction that the order to hold Kharkov would produce "another Stalingrad", on 14 August 1943 Manstein relieved Kempf and appointed General Otto Wöhler in his place. A few days later, Army Group Kempf was renamed the 8th Army.[21] Kharkov now constituted a deep German salient to the east, which prevented the red army from making use of this vital traffic and supply centre. Following boastful reports made by Soviet radio that Soviet troops had entered the city, when in fact it was still held by XI Army Corps, Joseph Stalin personally ordered its immediate capture.[22] General Raus the officer commanding the city takes up the story:

"It was clear that the Russians would not make a frontal assault on the projecting Kharkov salient but would attempt to breakthrough the narrowest part of XI Armeecorps defensive arc west of the city in order to encircle the town. We deployed all available anti-tank guns on the northern edge of the bottleneck, which rose like a bastion, and emplaced numerous 88mm flak guns in depth on the high ground. This antitank defence alone would not have been sufficient to repulse the expected Soviet mass tank attack, but at the last moment reinforcements in the form of the "Das Reich" Panzer Regiment arrived with a strong Panzer component; I immediately dispatched it to the most endangered sector. The ninety-six Panther tanks, thirty-five Tiger tanks, d and twenty-five Sturmgeschütz III self propelled assault guns had hardly taken their positions on 20 August 1943 when the first large scale attack got underway. However the Russian tanks had been recognized while they were still assembling in the villages and flood plains of a brook valley. Within a few minutes heavily laden Stukas came on in wedge formation and unloaded their cargoes of destruction in well timed dives on the enemy tanks caught in this congested area. Dark fountains of earth erupted skyward and were followed by heavy thunderclaps and shocks that resembled an earthquake. These were the heaviest, two-ton bombs, designed for use against battleships, which were all that Luftflotte 4 had left to counter the Russian attack. Soon all the villages occupied by Soviet tanks lay in flames. A sea of dust and smoke clouds illuminated by the setting sun hung over the brook valley, while dark mushrooms of smoke from burning tanks stood out in stark contrast. This gruesome picture bore witness to an undertaking that left death & destruction in its wake, hitting the Russians so hard that they could no longer launch their projected attack that day, regardless of Joseph Stalin's order. Such a severe blow inflicted on the Soviets had purchased badly needed time for XI Armeecorps to reorganize."[23]

The supply situation in Kharkov was now catastrophic; artillerymen after firing their last rounds, were abandoning their guns to fight as infantrymen. The army's supply depot had five trainloads of spare tank tracks leftover from "Zitadelle" but very little else. The high consumption of ammunition in the last month and a half had cut into supplies put aside for the last two weeks of August and the first two weeks of September; until the turn of the month the army would have to get along with fifty percent of its daily average requirements in artillery & tank ammunition. XI Army Corps now had a combat strength of only 4,000 infantrymen, one man for every ten yards of front.[24] General Erhard Raus explains the intensity of the constant Russian attacks:

"On 20 August the Russians avoided mass groupings of tanks, crossed the brook valley simultaneously in a number of places, and disappeared into the broad cornfields that were located ahead of our lines, ending at the east-west rollbahn several hundred metres in front of our main battle line. Throughout the morning Soviet tanks worked their way forward in the hollows up to the southern edges of the cornfields, then made a mass dash across the road in full sight. "Das Reich"'s Panthers caught the leading waves of T-34's with fierce defensive fire before they could reach our main battle line. Yet wave after wave followed, until Russian tanks flowed across in the protecting hollows and pushed forward into our battle positions. Here a net of anti-tank and flak guns, Hornet 88mm tank destroyers, and Wasp self-propelled 105mm field howitzers trapped the T-34's, split them into small groups, and put large numbers out of action. The final waves were still attempting to force a breakthrough in concentrated masses when the Tigers and StuG III self-propelled assault guns, which represented our mobile reserve s behind the front, attacked the Russian armour and repulsed it with heavy losses. The price paid by the 5th Guards Tank Army for this mass assault amounted to 184 knocked out T-34's.[25]

Wöhler, recognizing the hopelessness of the situation, did not prove anymore resolute, in view of the harsh realities facing the defenders of Kharkov, he knew that the depleted Infantry regiments could not hold their positions without copious artillery support. Two days after taking command of 8th Army, Wöhler also asked Manstein for permission to abandon the city. Regardless of Hitler's demand that the city be held, Wöhler and Manstein agreed that the city could not be defended for long, given the diminishing German strength and the overwhelming size of Soviet reserves.

On 21 August 1943, Manstein gave his consent to withdraw from Kharkov. The largely destroyed Soviet city, which changed hands several times during the war, was about to be recaptured by the Soviets for the last time. During the day of 22 August 1943, the Germans began their exodus from the city under great pressure from the Soviets. The 57th & 69th Armies pushed in from three sides with the coming of daylight. The Soviets sensed that the Germans were evacuating Kharkov, due to the lessening of artillery fire and diminishing resistance in the front lines. Later in the day, thunderous explosions were heard as ammo dumps were blown. Large German columns were then observed leaving the city and the Soviet troops pushed into the town itself. Moving out of Kharkov to the south, the Germans desperately fought to hold open a corridor through which a withdrawal could be made.

All along the corridor through which the 8th Army evacuated Kharkov, Soviet artillery and mortars pounded the withdrawal. Their planes gathered for the kill and attacked the German columns leaving the city, strafing & bombing the men & vehicles. After dark, the 89th Guards and 107th Rifle Divisions broke into the interior of the city, driving the last German rearguard detachments before them. Enormous fires were set by the Germans in hope of delaying the Soviet advance. The city became a hellish place of fire and smoke, artillery fire & desperate combat, punctuated by the explosions of supply dumps.

By 0200 on 23 August 1943, elements of the 183rd Rifle Division pushed into the city centre, reached the huge Dzerzhinsky Square and met men from the 89th Rifle Division. The Soviet troops hoisted a red banner over the city once again. By 1100, Kharkov and its outskirts had been liberated completely. The fourth and final battle for the city was over.[26]

Aftermath

By re-establishing a continuous front on Army Group South's left flank, the 4th Panzer Army and the 8th Army had for the moment, blunted a deadly thrust, but to the north and southeast fresh blows had already been dealt or were in the making. Employing the peculiar rippling effect that marked their offensives, the Red Army, thwarted in one place, had shifted to others. For the first time in the war they had the full strategic initiative, and they used it well.[27] The failure of Operation Citadel meant the Germans permanently lost the strategic initiative on the Eastern Front without any hope of regaining it, although Hitler refused to acknowledge it. The large manpower losses of the Wehrmacht in July and August 1943 severely restricted both Army Groups South & Centre to react to future thrusts during the winter and 1944. Operations Polkovodets Rumyantsev, along with the concurrent Operation Kutuzov marked the first time in the war that the Germans were not able to defeat a major Soviet offensive during the summer and regain their lost ground and the strategic initiative.[28]

Losses for the operation are difficult to establish due to large numbers of transfers and missing in action. Soviet casualties in the Belgorod–Kharkov sector during this operation are estimated to be 71,611 killed and 110,955 wounded; 1,864 tanks, 423 artillery guns, and 153 aircraft were lost.[4][5] German losses were at least 20,000 killed, 40,000 wounded, and ten thousand captured. German tank losses are estimated as several factors lower than Soviet tank losses.[29]

.jpg)

Footnotes

- a Kharkov is the Russian language name of the city (Kharkiv the Ukrainian one); both Russian and Ukrainian were official languages in the Soviet Union.[30]

- b The 905th Assault Gun Battalion, & the 7th & 48th flak regiments armed with the legendary '88' guns were also part of the Reserve.

- c Hitler claimed the loss of Kharkov would damage German prestige, particularly in Turkey. In the spring the Turkish Commander in Chief had inspected the defences as a guest of Armeeabteilung Kempf & pronounced them "Impregnable".

- d 1st Battalion, the 2 SS Das Reich Panzer Regiment left for France in May 1943, before the Battle of Kursk to receive its 'Panther' Tanks only returning in late August 1943.

Citations and notes

- 1 2 Krivosheev 1997, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 Koltunov p. 81.

- 1 2 Frieser 2007, p. 154.

- 1 2 Glantz & House 1995, p. 297.

- 1 2 3 4 Glantz & House 2015, p. 395.

- ↑ Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union since 1920 till Ukraine declared its independence from the Soviet Union on 24 August 1991 (Source: A History of Ukraine • The Land and Its Peoples, by Paul Robert Magocsi, University of Toronto Press, 2010, ISBN 1442610212 (pages 563/564 & 722/723))

- ↑ Glantz & House p. 241.

- ↑ Manstein p. 445

- ↑ Glantz & House 1995, p. 168.

- ↑ Glantz & House 2015, p. 221.

- ↑ Glantz & House 1995, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Frieser 2007, p. 196.

- 1 2 Glantz & House 2004, p. 249.

- ↑ Glantz & House 2004, p. 251.

- ↑ Glantz & House 1995, p. 170.

- 1 2 Glantz 2001, p. 333.

- 1 2 Panzer Operations The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus 1941-1945 bt Steven H Newton 2003 pp213-215

- ↑ Panzer Operations The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus 1941-1945 by Steven H Newton Da Capo Press edition 2003 pp213-216

- ↑ Decision in the Ukraine Summer 1943 II SS & III Panzer Corps, George M Nipe Jr, JJ Fedorowicz Publishing Inc. 1996 Page 324

- ↑ Stalingrad to Berlin - The German Defeat in the East by Earl F Ziemke by Dorset Press 1968 page 154

- ↑ Stalingrad to Berlin - The German Defeat in the East by Earl F Ziemke by Dorset Press 1968 page 153

- ↑ Panzer Operations The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus 1941-1945 bt Steven H Newton 2003 Page 242

- ↑ Panzer Operations The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus 1941-1945 by Steven H Newton 2003 pp 242-243

- ↑ Stalingrad to Berlin - The German Defeat in the East by Earl F Ziemke by Dorset Press 1968 page 156

- ↑ Panzer Operations The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus 1941-1945 bt Steven H Newton 2003 Page 244

- ↑ The Road to Berlin John Erickson Westview Press 1983 Page 121

- ↑ Stalingrad to Berlin - The German Defeat in the East by Earl F Ziemke by Dorset Press 1968 page 158

- ↑ Decision in the Ukraine Summer 1943 II SS & III Panzer Corps, George M Nipe Jr, JJ Fedorowicz Publishing Inc. 1996 Page 330

- ↑ Frieser 2007, p. 199.

- ↑ Language Policy in the Soviet Union by L.A. Grenoble & Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States by Routledge)

References

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz; Schmider, Klaus; Schönherr, Klaus; Schreiber, Gerhard; Ungváry, Kristián; Wegner, Bernd (2007). Die Ostfront 1943/44 – Der Krieg im Osten und an den Nebenfronten [The Eastern Front 1943–1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts]. Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg [Germany and the Second World War] (in German). VIII. München: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2.

- Glantz, David (2001). The military strategy of the Soviet Union: A History. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 9780714682006.

- Glantz, David Colossus reborn : the Red Army at war : 1941-1943. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press 2005. ISBN

- Glantz, David Soviet military deception in the Second World War. London, England: Routledge (1989). ISBN

- Glantz, David; House, Jonathan (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 9780700608997.

- Glantz, David M.; House, Jonathan M. (2015). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700621217 – via Project MUSE. (Subscription required (help)).

- Keitel, Wilhelm and Walter Görlitz The memoirs of Field-Marshal Keitel. New York, NY: Stein and Day 1965. ISBN

- Krivosheev, Grigoriy (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-280-7.

- Lisitskiy, P.I. and S.A. Bogdanov. Military Thought: Upgrading military art during the second period of the Great Patriotic War Jan-March, East View Publications, Gale Group, 2005

- Manstein, Erich von Lost Victories. St. Paul, MN: Zenith Press, 1982. ISBN 0-760320-54-3

- Decision in the Ukraine Summer 1943 II SS & III Panzerkorps, George M Nipe Jr, JJ Fedorowicz Publishing Inc. 1996 ISBN 0-921991-35-5

- Panzer Operations The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus 1941-1945 by Steven H Newton Da Capo Press edition 2003 ISBN 0-306-81247-9

- Stalingrad to Berlin - The German Defeat in the East by Earl F Ziemke Dorset Press 1968

- The Road to Berlin by John Erickson Westview Press 1983

- Decision in the Ukraine Summer 1943 II SS & III Panzerkorps, George M Nipe Jr, JJ Fedorowicz Publishing Inc. 1996 ISBN 0-921991-35-5

- Panzer Operations The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus 1941-1945 by Steven H Newton Da Capo Press edition 2003 ISBN 0-306-81247-9