Bektashi Order

| |

| Abbreviation | Bektashi Order/Bektashism |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1501 |

| Type | Dervish Order |

| Headquarters | Tirana |

Dedebaba | Edmond Brahimaj |

Key people |

Haji Bektash Veli – Patron Saint Balım Sultan - Founder |

| Website | bektashiorder.com |

The Bektashi Order, or the Bektashi Tariqah (Albanian: Tarikati Bektashi; Turkish: Bektaşi Tarîkatı), is a dervish order (tariqat) named after the 13th century Alevi Wali (saint) Haji Bektash Veli from Khorasan, but founded by Balım Sultan.[1] The order, whose headquarters is in Tirana, Albania, is mainly found throughout Anatolia and the Balkans, and was particularly strong in Albania, Bulgaria, and among Ottoman era Greek Muslims from the regions of Epirus, Crete and Macedonia. However, the Bektashi order does not seem to have attracted quite as many adherents from among Bosnian Muslims, who tended to favor more mainstream Sunni orders such as the Naqshbandiyya and Qadiriyya. The order represents the official ideology of Bektashism (Turkish: Bektaşilik).

In addition to the spiritual teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, the Bektashi order was later significantly influenced during its formative period by the Hurufis (in the early 15th century), the Qalandariyya stream of Sufism, and to varying degrees the Shia beliefs circulating in Anatolia during the 14th to 16th centuries. The mystical practices and rituals of the Bektashi order were systematized and structured by Balım Sultan in the 16th century after which many of the order's distinct practices and beliefs took shape.

A large number of academics consider Bektashism to have fused a number of Shia and Sufi concepts, although the order contains rituals and doctrines that are distinct. Throughout its history Bektashis have always had wide appeal and influence among both the Ottoman intellectual elite as well as the peasantry.

Beliefs

| |

|---|

|

|

|

The Bektashi Order is a Sufi order and shares much in common with other Islamic mystical movements, such as the need for an experienced spiritual guide—called a baba in Bektashi parlance — as well as the doctrine of "the four gates that must be traversed": the "Sharia" (religious law), "Tariqah" (the spiritual path), "Marifa" (true knowledge), "Haqiqah" (truth).

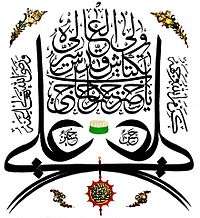

Bektashism places much emphasis on the concept of Wahdat-ul-Wujood وحدة الوجود, the "Unity of Being" that was formulated by Ibn Arabi. This has often been labeled as pantheism, although it is a concept closer to panentheism. Bektashism is also heavily permeated with Shiite concepts, such as the marked reverence of Ali, The Twelve Imams, and the ritual commemoration of Ashurah marking the Battle of Karbala. The old Persian holiday of Nowruz is celebrated by Bektashis as Imam Ali's birthday.

In keeping with the central belief of Wahdat-ul-Wujood the Bektashi see reality contained in Haqq-Muhammad-Ali, a single unified entity. Bektashi do not consider this a form of trinity. There are many other practices and ceremonies that share similarity with other faiths, such as a ritual meal (muhabbet) and yearly confession of sins to a baba (magfirat-i zunub مغفرة الذنوب). Bektashis base their practices and rituals on their non-orthodox and mystical interpretation and understanding of the Quran and the prophetic practice (Sunnah). They have no written doctrine specific to them, thus rules and rituals may differ depending on under whose influence one has been taught. Bektashis generally revere Sufi mystics outside of their own order, such as Ibn Arabi, Al-Ghazali and Jelalludin Rumi who are close in spirit to them.

Bektashis hold that the Quran has two levels of meaning: an outer (zahir ظاهر) and an inner (batin باطن). They hold the latter to be superior and eternal and this is reflected in their understanding of both the universe and humanity (This view can also be found in Ismailism—see Batiniyya).

Bektashism is also initiatic and members must traverse various levels or ranks as they progress along the spiritual path to the Reality. First level members are called aşıks عاشق. They are those who, while not having taken initiation into the order, are nevertheless drawn to it. Following initiation (called nasip) one becomes a mühip محب. After some time as a mühip, one can take further vows and become a dervish. The next level above dervish is that of baba. The baba (lit. father) is considered to be the head of a tekke and qualified to give spiritual guidance (irshad إرشاد). Above the baba is the rank of halife-baba (or dede, grandfather). Traditionally there were twelve of these, the most senior being the dedebaba (great-grandfather). The dedebaba was considered to be the highest ranking authority in the Bektashi Order. Traditionally the residence of the dedebaba was the Pir Evi (The Saint's Home) which was located in the shrine of Hajji Bektash Wali in the central Anatolian town of Hacıbektaş (aka Solucakarahüyük), known as Hajibektash complex.

History

The Bektashi order was widespread in the Ottoman Empire, their lodges being scattered throughout Anatolia as well as many parts of particularly the southern Balkans (especially Albania, Bulgaria, Epirus, and both Vardar Macedonia and Greek Macedonia) and also in the imperial city of Constantinople. The order had close ties with the Janissary corps, the elite infantry corp of the Ottoman Army, and therefore also became mainly associated with Anatolian and Balkan Muslims of Christian Orthodox convert origin, mainly Albanians and northern Greeks (although most leading Bektashi babas were of southern Albanian origin).[2] With the abolition of Janissaries, the Bektashi order was banned throughout the Ottoman Empire by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826. This decision was supported by the Sunni religious elite as well as the leaders of other, more orthodox, Sufi orders. Bektashi tekkes were closed and their dervishes were exiled. Bektashis slowly regained freedom with the coming of the Tanzimat era. After the foundation of republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk banned all Sufi orders and shut down the lodges in 1925. Consequently, the Bektashi leadership moved to Albania and established their headquarters in the city of Tirana. Among the most famous followers of Bektashi Sufism in the 19th century Balkans were Ali Pasha[3][4][5][6][7][8] and Naim Frashëri.

Despite the negative effect of this ban on Bektashi culture, most Bektashis in Turkey have been generally supportive of secularism to this day, since these reforms have relatively relaxed the religious intolerance that had historically been shown against them by the official Sunni establishment.

In the Balkans the Bektashi order had a considerable impact on the Islamization of many areas, primarily Albania and Bulgaria, as well as parts of Macedonia, particularly among Ottoman-era Greek Muslims from western Greek Macedonia such as the Vallahades. By the 18th century Bektashism began to gain a considerable hold over the population of southern Albania and northwestern Greece (Epirus and western Greek Macedonia). Following the ban on Sufi orders in the Republic of Turkey, the Bektashi community's headquarters was moved from Hacıbektaş in central Anatolia, to Tirana, Albania. In Albania the Bektashi community declared its separation from the Sunni community and they were perceived ever after as a distinct Islamic sect rather than a branch of Sunni Islam. Bektashism continued to flourish until the Second World War. After the communists took power in 1945, several babas and dervishes were executed and a gradual constriction of Bektashi influence began. Ultimately, in 1967 all tekkes were shut down when Enver Hoxha banned all religious practice. When this ban was rescinded in 1990 the Bektashism reestablished itself, although there were few left with any real knowledge of the spiritual path. Nevertheless, many "tekkes" (lodges) operate today in Albania. The most recent head of the order in Albania was Hajji Reshat Bardhi Dedebaba (1935–2011) and the main tekke has been reopened in Tirana. In June 2011 Baba Edmond Brahimaj was chosen as the head of the Bektashi order by a council of Albanian babas. Today sympathy for the order is generally widespread in Albania where approximately 20% of Muslims identify themselves as having some connection to Bektashism.

There are also important Bektashi communities among the Albanian communities of Macedonia and Kosovo, the most important being the Harabati Baba Tekke in the city of Tetovo, which was until recently under the guidance of Baba Tahir Emini (1941–2006). Following the death of Baba Tahir Emini, the dedelik of Tirana appointed Baba Edmond Brahimaj (Baba Mondi), formerly head of the Turan Tekke of Korçë, to oversee the Harabati baba tekke. A splinter branch of the order has recently sprung up in the town of Kičevo which has ties to the Turkish Bektashi community under Haydar Ercan Dede rather than Tirana. A smaller Bektashi tekke, the Dikmen Baba Tekkesi, is in operation in the Turkish-speaking town of Kanatlarci, Macedonia that also has stronger ties with Turkey's Bektashis. In Kosovo the relatively small Bektashi community has a tekke in the town of Đakovica (Gjakovë) and is under the leadership of Baba Mumin Lama and it recognizes the leadership of Tirana.

In Bulgaria, the türbes of Kıdlemi Baba, Ak Yazılı Baba, Demir Baba and Otman Baba function as heterodox Islamic pilgrimage sites and before 1842 were the centers of Bektashi tekkes.[9]

Bektashis continue to be active in Turkey and their semi-clandestine organizations can be found in Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir. There are currently two rival claimants to the dedebaba in Turkey: Mustafa Eke and Haydar Ercan.

A large functioning Bektashi tekke was also established in the United States in 1954 by Baba Rexheb. This tekke is found in the Detroit suburb of Taylor and the tomb (türbe) of Baba Rexheb continues to draw pilgrims of all faiths.

Arabati Baba Teḱe controversy

In 2002 a group of armed members of the Islamic Community of Macedonia (ICM), the legally recognized organization which claims to represent all Muslims in the Republic of Macedonia, invaded the Arabati Baba Teḱe in an attempt to reclaim the tekke as a mosque, although the facility has never functioned as such. Subsequently, the Bektashi community of the Republic of Macedonia has sued the Macedonian government for failing to restore the tekke to the Bektashi community, pursuant to a law passed in the early 1990s returning properties previously nationalized under the Yugoslav government. The law, however, deals with restitution to private citizens, rather than religious communities.[10] The ICM claim to the tekke is based upon their contention to represent all Muslims in the Republic of Macedonia; and indeed, they are one of two Muslim organizations recognized by the government, both Sunni. The Bektashi community filed for recognition as a separate religious community with the Macedonian government in 1993, but the Macedonian government has refused to recognize them.[10]

Poetry and literature

Poetry plays an important role in the transmission of Bektashi spirituality. Several important Ottoman-era poets were Bektashis, and Yunus Emre, the most acclaimed poet of the Turkish language, is generally recognized as a subscriber to the Bektashi order.

A poem from Bektashi poet Balım Sultan (died 922 AH/1516 ):

- İstivayı özler gözüm, (My eye seeks out repose,)

- Seb'al-mesânîdir yüzüm, (my face is the 'oft repeated seven (i.e. the Sura Al-Fatiha),)

- Ene'l-Hakk'ı söyler sözüm, (My words proclaim "I am the Truth",)

- Miracımız dardır bizim, (Our ascension is (by means of) the scaffold,)

- Haber aldık muhkemattan, (We have become aware through the "firm letters",)

- Geçmeyiz zâttan sıfattan, (We will not abandon essence or attributes,)

- Balım nihan söyler Hakk'tan, (Balım speaks arcanely of God)

- İrşâdımız sırdır bizim. (Our teaching is a mystery.[11])

Humour

The telling of jokes and humorous tales is an important part of Bektashi culture and teaching. Frequently these poke fun at conventional religious views by counterpoising the Bektashi dervish as an iconoclastic figure. For example:

A Bektashi was praying in the mosque. While those around him were praying "May God grant me faith," he muttered "May God grant me plenty of wine." The imam heard him and asked angrily why instead of asking for faith like everyone else, he was asking God for something sinful. The Bektashi replied, "Well, everyone asks for what they don't have."

A Bektashi was a passenger in a rowing boat travelling from Eminönü to Üsküdar in Istanbul. When a storm blew up, the boatman tried to reassure him by saying "Fear not—God is great!" the Bektashi replied, "Yes, God is great, but the boat is small."

An imam was preaching about the evils of alcohol and asked "If you put a pail of water and a pail of rakı in front of a donkey, which one will he drink from?" A Bektashi in the congregation immediately answered. "The water!" "Indeed," said the imam, "and why is that?" "Because he's an ass."[12]

Historical evolutionary development of Bektashi faith throughout Anatolia and the Balkans

Gallery

Arabati Baba Tekke, in Tetovo

Arabati Baba Tekke, in Tetovo Bektashi Tekke

Bektashi Tekke Kutuklu Baba Tekke in Greece.

Kutuklu Baba Tekke in Greece.

See also

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| The Fourteen Infallibles | |||

|

|||

| Principles | |||

| Other beliefs | |||

| Practices | |||

| Holy cities | |||

| Groups | |||

|

|

|||

| Scholarship | |||

| Hadith collections | |||

| Related topics | |||

| Related portals | |||

|

|||

- Ashurkhana

- Bayramiyya

- Cem Evi

- Imambargah

- Jem (Alevism)

- Khalwatiyya

- Khalwatkhana

- Kızılbaş

- Mejlis

- Musallah

- Mawlawiyyah

- Naqshbandiyyah

- Qadiriyya

- Qizilbash-Alevi

- Sema

- Tekkes

- Zahediyya

- Zawiyya

Notes

- ↑ "Bektāšīya". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 1989-12-15. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ Nicolle, David; pg 29

- ↑ Miranda Vickers (1999), The Albanians: A Modern History, London: I.B. Tauris, p. 22, ISBN 9781441645005,

Around that time, Ali was converted to Bektashism by Baba Shemin of Kruja...

- ↑ H.T.Norris (2006), Popular Sufism in Eastern Europe: Sufi Brotherhoods and the Dialogue with Christianity and 'Heterodoxy' (Routledge Sufi), Routledge Sufi series (20), Routledge, p. 79, ISBN 9780203961223, OCLC 85481562,

...and the tomb of Ali himself. Its headstone was capped by the crown (taj) of the Bektashi order.

- ↑ Robert Elsie (2004), Historical Dictionary of Albania, European historical dictionaries (42), Scarecrow Press, p. 40, ISBN 9780810848726, OCLC 52347600,

Most of the Southern Albania and Epirus converted to Bektashism, initially under the influence of Ali Pasha Tepelena, "the Lion of Janina", who was himself a follower of the order.

- ↑ Vassilis Nitsiakos, On the Border: Transborder Mobility, Ethnic Groups and Boundaries along the Albanian-Greek Frontier (Balkan Border Crossings- Contributions to Balkan Ethnography), Balkan border crossings (1), Berlin: Lit, p. 216, ISBN 9783643107930, OCLC 705271971,

Bektashism was widespread during the reign of Ali Pasha, a Bektashi himself,...

- ↑ Gerlachlus Duijzings (2010), Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 82, ISBN 9780231120982, OCLC 43513230,

The most illustrious among them was Ali Pasha (1740-1822), who exploited the organisation and religious doctrine...

- ↑ Stavro Skendi (1980), Balkan Cultural Studies, East European monographs (72), Boulder, p. 161, ISBN 9780914710660, OCLC 7058414,

The great expandion of Bektashism in southern Albania took place during the time of Ali Pasha Tepelena, who is believed to have been a Bektashi himself

- ↑ Lewis, Stephen (2001). "The Ottoman Architectural Patrimony in Bulgaria". EJOS. Utrecht. 30 (IV). ISSN 0928-6802.

- 1 2 Muslims of Macedonia

- ↑ Algar, Hamid. The Hurufi Influence on Bektashism: Bektachiyya, Estudés sur l'ordre mystique des Bektachis et les groupes relevant de Hadji Bektach. Istambul: Les Éditions Isis. pp. 39–53.

- ↑ Hacıbektaş Web

- ↑ Balcıoğlu, Tahir Harimî, Türk Tarihinde Mezhep Cereyanları - The course of madhhab events in Turkish history, (Preface and notes by Hilmi Ziya Ülken), Ahmet Sait Press, 271 pages, Kanaat Publications, Istanbul, 1940. (in Turkish)

- 1 2 Ocak, Ahmet Yaşar XII yüzyılda Anadolu'da Babâîler İsyânı - Babai Revolt in Anatolia in the Twelfth Century, pages 83-89, Istanbul, 1980. (in Turkish)

- ↑ "Encyclopaedia of Islam of the Foundation of the Presidency of Religious Affairs," Volume 4, pages 373-374, Istanbul, 1991.

- ↑ Balcıoğlu, Tahir Harimî, Türk Tarihinde Mezhep Cereyanları - The course of madhhab events in Turkish history – Two crucial front in Anatolian Shiism: The fundamental Islamic theology of the Hurufiyya madhhab, (Preface and notes by Hilmi Ziya Ülken), Ahmet Sait Press, page 198, Kanaat Publications, Istanbul, 1940. (in Turkish)

- ↑ According to Turkish scholar, researcher, author and tariqa expert Abdülbaki Gölpınarlı, "Qizilbashs" ("Red-Heads") of the 16th century - a religious and political movement in Azerbaijan that helped to establish the Safavid dynasty - were nothing but "spiritual descendants of the Khurramites". Source: Roger M. Savory (ref. Abdülbaki Gölpinarli), Encyclopaedia of Islam, "Kizil-Bash", Online Edition 2005.

- ↑ According to the famous Alevism expert Ahmet Yaşar Ocak, "Bektashiyyah" was nothing but the reemergence of Shamanism in Turkish societies under the polishment of Islam. (Source: Ocak, Ahmet Yaşar XII yüzyılda Anadolu'da Babâîler İsyânı - Babai Revolt in Anatolia in the Twelfth Century, pages 83-89, Istanbul, 1980. (in Turkish))

References

- Nicolle, David; UK (1995). The Janissaries (5th). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-413-X.

- Muhammed Seyfeddin Ibn Zulfikari Derviş Ali; Bektaşi İkrar Ayini, Kalan Publishing, Translated from Ottoman Turkish by Mahir Ünsal Eriş, Ankara, 2007 Turkish