Baul

| Baul songs | |

|---|---|

| Country | Bangladesh |

| Domains | Social practices, rituals and festive events |

| Reference | 00107 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2008 (3rd session) |

| List | Representative |

| |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bengal |

|---|

|

|

History

Genres Institutions

Awards

|

|

Music and performing arts |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

|

Mother tongue |

|

Regions |

|

Faith groups |

|

Visual arts |

|

Martial arts |

|

Other |

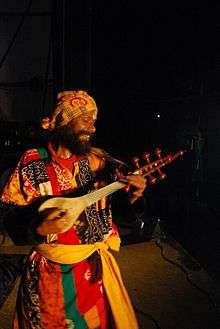

The Baul (Bengali: বাউল) are a group of mystic minstrels from Bengal, which includes the Indian State of West Bengal and the country of Bangladesh. Bauls constitute both a syncretic religious sect and a musical tradition. Bauls are a very heterogeneous group, with many sects, but their membership mainly consists of Vaishnava Hindus and Sufi Muslims.[1][2] They can often be identified by their distinctive clothes and musical instruments. Not much is known of their origin. Lalon Fokir is regarded as the most important poet-practitioner of the Baul tradition.[3][4][5] Baul music had a great influence on Rabindranath Tagore's poetry and on his music (Rabindra Sangeet).[6]

Although Bauls comprise only a small fraction of the Bengali population, their influence on the culture of Bengal is considerable. In 2005, the Baul tradition was included in the list of "Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity" by UNESCO.[7]

Etymology

The word Baul has its etymological origin in the Sanskrit word Vātūla ("mad", from vāyu - "air" or "wind") and is used for someone who is possessed or crazy. Bauls are an extension of the Sahajiya philosophy, which in turn derives from the Nath tradition. They believe in living the world as a half-sanyasi.[8]

The origin of the word Baul is debated. Some modern scholars, like Shashibhusan Das Gupta have suggested that it may be derived either from Sanskrit word vatula, which means "enlightened, lashed by the wind to the point of losing one's sanity, god's madcap, detached from the world, and seeker of truth", or from vyakula, which means "restless, agitated" and both of these derivations are consistent with the modern sense of the word, which denotes the inspired people with an ecstatic eagerness for a spiritual life, where a person can realise his union with the eternal beloved – the Moner Manush (the person of the heart).[9]

History

The origin of Bauls is not known exactly, but the word "Baul" has appeared in Bengali texts as old as the 15th century. The word is found in the Chaitanya Bhagavata of Vrindavana Dasa Thakura as well as in the Chaitanya Charitamrita of Krishnadasa Kaviraja.[10] Some scholars maintain that it is not clear when the word took its sectarian significance, as opposed to being a synonym for the word madcap, agitated. The beginning of the Baul movement was attributed to Birbhadra, the son of the Vaishnavite saint Nityananda, or to the 8th century Persian minstrels called Ba'al. Bauls are a part of the culture of rural Bengal. Whatever their origin, Baul thought has mixed elements of Tantra, Sufi Islam, Vaishnavism and Buddhism. They are thought to have been influenced by the Hindu tantric sect of the Kartabhajas, as well as Tantric Vaishnava schools like the Vaishnava-Sahajiya. Some scholars find traces of these thoughts in the ancient practices of Yoga as well as the Charyapadas, which are Buddhist hymns that are the first known example of written Bengali. The Bauls themselves attribute their lack of historical records to their reluctance to leave traces behind. Dr. Jeanne Openshaw writes that the music of the Bauls appears to have been passed down entirely in oral form until the end of the 19th century, when it was first transcribed by outside observers.[11]

The Bauls were recorded as a major sect as early as mid 18th century.

Regarding the origins of the sect, one recent theory suggests that Bauls are descendants of a branch of Sufism called ba'al. Votaries of this sect of Sufism in Iran, dating back to the 8th-9th centuries, were fond of music and participated in secret devotional practices. They used to roam about the desert singing. Like other Sufis, they also entered the South Asian subcontinent and spread out in various directions. It is also suggested that the term derives from the Sanskrit words vatul (mad, devoid of senses) and vyakul (wild, bewildered) which Bauls are often considered.

Like the ba'al who rejects family life and all ties and roams the desert, singing in search of his beloved, the Baul too wanders about searching for his maner manus (the ideal being). The madness of the Baul may be compared to the frenzy or intoxication of the Sufi diwana. Like the Sufi, the Baul searches for the divine beloved and finds him housed in the human body. Bauls call the beloved sain (lord), murshid (guide), or guru (preceptor), and it is in his search that they go 'mad'.

There are two classes of Bauls: ascetic Bauls who reject family life and Bauls who live with their families. Ascetic Bauls renounce family life and society and survive on alms. They have no fixed dwelling place, but move from one akhda to another. Men wear white lungis and long, white tunics; women wear white saris. They carry a jhola or shoulder bag for alms. They do not beget or rear children. They are treated as jyante mara or outcastes. Women, dedicated to the service of ascetics, are known as sevadasis (seva, service+dasi, maidservant). A male Baul can have one or more sevadasis, who are associated with him in the act of devotion. Until 1976 the district of Kushtia had 252 ascetic Bauls. In 1982-83 the number rose to 905; in 2000, they numbered about 5,000.

Those who choose family life live with their wives, children and relations in a secluded part of a village. They do not mix freely with other members of the community. Unlike ascetic Bauls, their rituals are less strict. In order to become Bauls, they recite some mystic verses and observe certain rituals.[12]

Concepts and practices

Baul music celebrates celestial love, but does this in very earthy terms, as in declarations of love by the Baul for his bosh-tomi or lifemate. With such a liberal interpretation of love, it is only natural that Baul devotional music transcends religion and some of the most famous baul composers, such as Lalon Fokir, criticised the superficiality of religious divisions:

Everyone asks: "Lalan, what's your religion in this world?"

Lalan answers: "How does religion look?"

I've never laid eyes on it.

Some wear malas [Hindu rosaries] around their necks,

some tasbis [Muslim rosaries], and so people say

they've got different religions.

But do you bear the sign of your religion

when you come or when you go?[13]

The famous Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore was greatly influenced and inspired by Bauls. Here is a famous Rabindrasangeet (Tagore song), heavily influenced by Baul theme:

amar praner manush achhe prane

tai here taye shokol khane

Achhe she noyōn-taray, alōk-dharay, tai na haraye--

ogo tai dekhi taye Jethay shethay

taka-i ami je dik-paneThe man of my heart dwells inside me.

Everywhere I look, it is he.

In my every sight, in the sparkle of light

Oh, I can never lose him--

Here, there and everywhere,

Wherever I turn, he is right there!

Their religion is based on an expression of the body (Deho Sadhana), and an expression of the mind (Mana Sadhana). Some of their rituals are kept hidden from outsiders, as they might be thought to be repulsive or hedonistic. Bauls concentrate much of their mystic energies on the four body fluids, on the nine-doors (openings of the body), on prakriti as "nature" or "primal motive force", and on breath Sadhana.

Music

The music of the Bauls, Baul Sangeet, is a particular type of folk song. Its lyrics carry influences of the Hindu bhakti movements and the suphi, a form of Sufi song exemplified by the songs of Kabir. Their music represents a long heritage of preaching mysticism through songs in Bengal, as in the Shahebdhoni or Bolahadi sects.

Bauls pour out their feelings in their songs but never bother to write them down. Theirs is essentially an oral tradition. It is said that Lalon Fokir (1774 -1890), the greatest of all Bauls, continued to compose and sing songs for decades without ever stopping to correct them or put them on paper. It was only after his death that people thought of collecting and compiling his repertoire.

Their lyrics intertwine a deep sense of mysticism, a longing for oneness with the divine. An important part of their philosophy is "Deha tatta", a spirituality related to the body rather than the mind. They seek the divinity in human beings. Metaphysical topics are dwelt upon humbly and in simple words. They stress remaining unattached and unconsumed by the pleasures of life even while enjoying them. To them we are all a gift of divine power and the body is a temple, music being the path to connect to that power.[8][14]

Bauls use a number of musical instruments: the most common is the ektara, a one-stringed "plucked drum" drone instrument, carved from the epicarp of a gourd, and made of bamboo and goatskin. Others include the dotara, a long-necked fretless lute (while the name literally means "two stringed" it usually has four metal strings) made of the wood of a jackfruit or neem tree; besides khamak, one-headed drum with a string attached to it which is plucked. The only difference from ektara is that no bamboo is used to stretch the string, which is held by one hand, while being plucked by another.[15] Drums like the duggi, a small hand-held earthen drum, and dhol and khol; small cymbals called khartal and manjira, and the bamboo flute are also used. Ghungur and nupur are anklets with bells that ring while the person wearing them dances.

A Baul family played on stage in London for The Rolling Stones' Hyde Park concerts in 1971, '72 and '78 in front of thousands.[14]

Rabindranath Tagore

The songs of the Bauls and their lifestyle influenced a large swath of Bengali culture, but nowhere did it leave its imprint more powerfully than on the work of Rabindranath Tagore, who talked of Bauls in a number of speeches in Europe in the 1930s. An essay based on these was compiled into his English book The Religion of Man:

The Bauls are an ancient group of wandering minstrels from Bengal, who believe in simplicity in life and love. They are similar to the Buddhists in their belief in a fulfillment which is reached by love's emancipating us from the dominance of self.

Where shall I meet him, the Man of my Heart?

He is lost to me and I seek him wandering from land to land.

- I am listless for that moonrise of beauty,

- which is to light my life,

- which I long to see in the fullness of vision

- in gladness of heart. [p.524]

The above is a translation of the famous Baul song by Gagan Harkara: Ami kothai pabo tare, amar moner manush je re. The following extract is a translation of another song:

My longing is to meet you in play of love, my Lover;

But this longing is not only mine, but also yours.

For your lips can have their smile, and your flute

- its music, only in your delight in my love;

- and therefore you importunate, even as I am.

The poet proudly says: 'Your flute could not have its music of beauty if your delight were not in my love. Your power is great—and there I am not equal to you—but it lies even in me to make you smile and if you and I never meet, then this play of love remains incomplete.'

The great distinguished people of the world do not know that these beggars—deprived of education, honour and wealth—can, in the pride of their souls, look down upon them as the unfortunate ones who are left on the shore for their worldly uses but whose life ever misses the touch of the Lover's arms.

This feeling that man is not a mere casual visitor at the palace-gate of the world, but the invited guest whose presence is needed to give the royal banquet its sole meaning, is not confined to any particular sect in India.

A large tradition in medieval devotional poetry from Rajasthan and other parts of India also bear the same message of unity in celestial and romantic love and that divine love can be fulfilled only through its human beloved.

Tagore's own compositions were powerfully influenced by Baul ideology. His music also bears the stamp of many Baul tunes. Other Bengali poets, such as Kazi Nazrul Islam, have also been influenced by Baul music and its message of non-sectarian devotion through love.

Rabindranath Tagore was greatly influenced and inspired by Bauls. Here is a famous Rabindrasangeet (Tagore song), heavily influenced by Baul theme:

Amar praner manush achhé prané

Tai heri taye sakol khane

Achhe shé nayōntaray, alōk-dharay, tai na haraye--

- Ogo tai dekhi taye jethay sethay

- Taka-i ami jé dik-pané

The man of my heart dwells inside me.

Everywhere I behold, it's Him!

In my every sight, in the sparkle of light

- Oh I can never lose Him --

- Here, there and everywhere,

- Wherever I turn, right in front is He![16]

All bāulas shared only one belief in common—that God is hidden within the heart of man and neither priest, prophet, nor the ritual of any organized religion will help one to find Him there. They felt that both temple and mosque block the path to truth; the search for God must be carried out individually and independently.[17]

As described by Ramakrishna

From page 513 of the Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita:

According to the Sakti cult the siddha is called a koul, and according to the Vedanta, a paramahamsa. The Bauls call him a sai. They say, "No one is greater than a sai." The sai is a man of supreme perfection. He doesn't see any differentiation in the world. He wears a necklace, one half made of cow bones and the other of the sacred tulsi-plant. He calls the Ultimate Truth "Alekh", the "Incomprehensible One". The Vedas call it "Brahman". About the jivas the Bauls say, "They come from Alekh and they go unto Alekh." That is to say, the individual soul has come from the Unmanifest and goes back to the Unmanifest. The Bauls will ask you, "Do you know about the wind?" The "wind" means the great current that one feels in the subtle nerves, Ida, Pingala, and Sushumna, when the Kundalini is awakened. They will ask you further, "In which station are you dwelling?" According to them there are six "stations", corresponding to the six psychic centers of Yoga. If they say that a man dwells in the "fifth station", it means that his mind has climbed to the fifth centre, known as the Visuddha chakra. (To Mahendranath Gupta) At that time he sees the Formless.

Impact of Kalachand Vidyalankar upon Sahajia Bauls

To the Spiritual Monk, Kalachand Vidyalankar, Hinduism is not a religion; it is a social guideline – how to lead an ideal and spiritual life. It's a culture which inspired the mankind for ages. He believed, it is knowledge (Vedas), not religion which can uplift mankind from narrowness of mind. To cross the domestic boundaries and superstitious bondages, he ordained the basic education is a must for all irrespective of caste, creed, sex and nationality.

There remains a primordial integrity between the gospel of Kalachand and the Spiritual ideology of Bauls and Fokirs. The comparison between the two form of spirituality and their humanistic aspects can be an elaborate exercise. In fact plenty of material and avenues does not exist to deliberate on the issue. However, it can certainly be an intriguing and long research topic for the keen scholars of social anthropology.

But, for the sake of simplifications, we would like to shorten the issue by just comparing the essence of the Baul songs inspired by Kalachand with another which later Rabindranath Tagore described as Religion of Man. Of course this will leave open a wide area of hitherto unexplored treasure trove. But these two lyrics by two spiritual institutions of Bengal will nevertheless shed ample light on difference of perceptions. In fact, the difference can be quite poignant with a vast shift of the basics on which the concept of spiritualism is built on. To many, Kalachand Vidyalankar is known as Kalachand Fokir and his Baul followers are known as 'Kalachandi Mat'(Kalachand's cult) or 'Kalachandi Akhra'.

The metaphysical Baul lyrics raise a basic question- that if there is a single creator then why so many religions exist? This is a pertinent problem in today’s world; we all know that the different ‘Gods’ have created acrimony between races and sects and as of today this concept of different ‘Gods’ remains the most decisive divisive force on planet Earth. In this context it would perhaps be appropriate to note that the Bauls in essence do not believe in the diktat of denizens of the Heaven; there is no world for the Bauls beyond which can be perceived by the direct human senses.

They just do not believe in the pious ‘other world’ and most of the times deny the presence of super powers. Looking from a different angle it can be said that according to the Bauls and Fokirs, ‘God’ resides in each human being and it is for the human being to realise this truth. This is the primary search the Bauls and Fokirs undertake, and according to them human beings are the best exponents of spirituality ever to tread on this Earth.

Present status

Bauls are found in the Indian state of West Bengal and the eastern parts of Bihar and Jharkhand and the country of Bangladesh. The Baul movement was at its peak in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but even today one comes across the occasional Baul with his Ektara (one-stringed musical instrument) and begging bowl, singing across the farflung villages of rural Bengal. Travelling in local trains and attending village fairs are good ways to encounter Bauls.

Every year, in the month of Falgun (February to March), "Lalon Smaran Utshab" (Lalon memorial festival) is held in the shrine of Lalon in Kushtia, Bangladesh, where bauls and devotees of Lalon from Bangladesh and overseas come to perform and highlight the mystics of Lalon.[18]

Palli Baul Samaj Unnayan Sangstha (PBSUS), a Bangladeshi organisation, has been working to uphold and preserve the ‘baul’ traditions and philosophy for the last nine years. The organisation often arranges programmes featuring folk songs for urban audiences.[19]

Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy often organises national and international festivals and seminars, featuring the Baul music and the importance of preservation of Baul tradition.

In the village of Jaydev Kenduli, a Mela (fair) is organised in memory of the poet Jayadeva on the occasion of Makar Sankranti in the month of Poush. So many Bauls assemble for the mela that it is also referred to as "Baul Fair".

In the village of Shantiniketan during Poush Mela, numerous Bauls also come together to enthrall people with their music.

For the last five years a unique show has been organised in Kolkata, called "Baul Fakir Utsav". Bauls from several districts of Bengal as well as Bangladesh come to perform. The 6th Baul fakir Utsav will be held on 8 and 9 January 2011. The Utsav is a continuous 48-hour musical experience.

There are also the Western Bauls in America and Europe under the spiritual direction of Lee Lozowick, a student of Yogi Ramsuratkumar. Their music is quite different (rock /gospel/ blues) but the essence of the spiritual practices of the East is well maintained.[20]

In Bangalore near Electronic City Dr. Shivshankar Bhattacharjee has started Boul Sammelon (Gathering of Baulls) on 7-9th April-2017 on the occasion of the inauguration of Sri Sri Kali Bari (Goodness Kali's Temple). First time it held in Bangalore to embrace the Boul culture. More that 50 Bouls participated and sang soulful songs.

Currently another version of Baul called the folk fusion also called baul rock is also greatly accepted by the audience, especially in West Bengal. Kartik das baul being a traditional folk singer, who has taken baul to different heights is being associated with folk fusion. This type of baul was brought into the world of music by Bolepur bluez, which was world's first folk fusion band.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Baul (Indian music)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 18 June 2015.

- ↑ "Bauled over". The Times of India. 6 Feb 2010.

- ↑ Multiple editors (2007). World and its People: Eastern and Southern Asia. New York: Marshal Cavendish Corporation. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3.

- ↑ Khan, Shamsuzzaman (editor) (1987). Folklore of Bangladesh V-1. Dhaka: Bangla Academy. p. 257.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Kabir (1985). Folk Poems From Bangladesh. Dhaka: Bangla Academy. pp. ii.

- ↑ Hoiberg, Dale; Ramchandani, Indu (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. p. 172. ISBN 0-85229-760-2.

- ↑ Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. UNESCO. 25 September 2005.

- 1 2 "Bauls of Bengal". Hinduism.about.com. 10 April 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ↑ Das Gupta, Shashibhusan (1946, reprint 1995). Obscure Religious Cults, Calcutta: Firma KLM, ISBN 81-7102-020-8, pp.160-1

- ↑ Das Gupta, Shashibhusan (1946, reprint 1995). Obscure Religious Cults, Calcutta: Firma KLM, ISBN 81-7102-020-8, p.160ff

- ↑ Openshaw, Jeanne. Seeking Bāuls of Bengal p.56

- ↑ Karim, Anwarul (2012). "Baul". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Lopez, Donald (1995). Religions in India in Practice - "Baul Songs". Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 187–208. ISBN 0-691-04324-8.

- 1 2 Music (26 July 2011). "Bauls of Bengal – The Liberation Seekers". Emaho Magazine. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ↑ Dilip Ranjan Barthakur (2003). The Music And Musical Instruments Of North Eastern India. Mittal Publications. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-81-7099-881-5. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ↑ "Bauls of Bangladesh". www.scribd.com

- ↑ Edward C. Dimock, Jr., "Rabindranath Tagore—’The Greatest of the Bāuls of Bengal,’" The Journal of Asian Studies (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Association for Asian Studies), vol. 19, no. 1 (Nov. 1959), 36–37.

- ↑ Aman, Amanur (13 March 2012). "Lalon Smaran Utshab ends". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ↑ info@banglamusic.com (20 January 2012). "Baul Mela 2009 Bangla Music – Bangla Song Bangla Video Bengali Music Mp3 News". Banglamusic.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ↑ Helen Crovetto, "Embodied Knowledge and Divinity: The Hohm Community as Western-style Bāuls," Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 10, no. 1 (August 2006): pp. 69-95.

Bibliography

- Enamul Haq, Muhammad (1975), A history of Sufism in Bengal, Asiatic Society, Dhaka.

- Qureshi, Mahmud Shah (1977), Poems Mystiques Bengalis. Chants Bauls Unesco. Paris.

- Siddiqi, Ashraf (1977), Our Folklore Our Heritage, Dhaka.

- Karim, Anwarul (1980), The Bauls of Bangladesh. Lalon Academy, Kushtia.

- Mukherjee, Prithwindra (1981), Chants Caryâ du bengali ancien (édition bilingue), Le Calligraphe, Paris.

- Mukherjee, Prithwindra (1985), Bâul, les Fous de l'Absolu (édition trilingue), Ministère de la Culture/ Findakly, Paris

- Capwell, Charles (1986), The Music of the Bauls of Bengal. Kent State University Press, USA 1986. ISBN 0-87338-317-6.

- Dimock, Edward C. (1989), The Place of the Hidden Moon: Erotic Mysticism in the Vaisnava-Sahajiya Cult of Bengal, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. ISBN 0-226-15237-5, ISBN 978-0-226-15237-0

- Bandyopadhyay, Pranab (1989), Bauls of Bengal. Firma KLM Pvt, Ltd., Calcutta.

- Mcdaniel, June (1989), The Madness of the Saints. Chicago.

- Sarkar, R. M. (1990), Bauls of Bengal. New Delhi.

- Brahma, Tripti (1990), Lalon : His Melodies. Calcutta.

- Gupta, Samir Das (2000), Songs of Lalon. Sahitya Prakash, Dhaka.

- Karim, Anwarul (2001), Rabindranath O Banglar Baul (in Bengali), Dhaka.

- Openshaw, Jeanne (2002). Seeking Bauls of Bengal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81125-5.

- Baul, Parvathy (2005). Song of the Great Soul: An Introduction to the Baul Path. Ekatara Baul Sangeetha Kalari.

- Capwell, Charles (2011), Sailing on the Sea of Love THE MUSIC OF THE BAULS OF BENGAL, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. ISBN 978-0-85742-004-6

- Sen, Mimlu (2009), Baulsphere, Random House, ISBN 81-8400-055-3

- Sen, Mimlu (2010), The Honey Gatherers, Rider Books, ISBN 978-1-84604-189-1

- Knight, Lisa I. (2011). Contradictory Lives: Baul Women in India and Bangladesh. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977354-1.

- Mukherjee, Prithwindra (2014), Le Spontané: chants Caryâ et Bâul, Editions Almora, Paris.

References

|

|

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baul. |

- Baul Archive Baularchive is dedicated to the memory of Professor Edward C. Dimock, Jr. who inspired generations of American and Bengali scholars with the poetry and philosophy of Baul songs. It is the culmination of Sally Grossman’s forty-plus year long interest in the Bauls and has been conceived, inspired, and generously supported by her with the advice and cooperation of Charles Capwell.

- Sadhu Guru Boishnob Recordings - A record label dedicated to producing high quality field recordings of Baul-Fakir songs and music from Bengal.

- Lalon Song's Archive Lalon Song's Archive

- Parvathy Baul is a singer, painter and storyteller from West Bengal. Visit : www.parvathybaul.srijan.asia.

- For The Sake Of The Song Reportage by Deborah Baker

- PUNKCAST#522 Video of Babukishan Das and Dharma Bums performing in NYC, 16 Aug 2004. (RealPlayer)

- Baul- The Folk Music of Bengal - Arghya Chatterjee: (Internet Archive)

- Satyananda Das Baul