Battle of Tsushima

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Tsushima (Russian: Цусимское сражение, Tsusimskoye srazheniye), also known as the Battle of Tsushima Strait and the Naval Battle of the Sea of Japan (Japanese: 日本海海戦, Nihonkai-Kaisen) in Japan, was a major naval battle fought between Russia and Japan during the Russo-Japanese War. It was naval history's only decisive sea battle fought by modern steel battleship fleets,[2][3] and the first naval battle in which wireless telegraphy (radio) played a critically important role. It has been characterized as the "dying echo of the old era – for the last time in the history of naval warfare, ships of the line of a beaten fleet surrendered on the high seas."[4]

It was fought on 27–28 May 1905 (14–15 May in the Julian calendar then in use in Russia) in the Tsushima Strait between Korea and southern Japan. In this battle the Japanese fleet under Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō destroyed two-thirds of the Russian fleet, under Admiral Zinovy Rozhestvensky, which had traveled over 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 km) to reach the Far East. In London in 1906, Sir George Sydenham Clarke wrote, "The battle of Tsu-shima is by far the greatest and the most important naval event since Trafalgar";[5] decades later, historian Edmund Morris agreed with this judgment.[6] The destruction of the Russian navy caused a bitter reaction from the Russian public, which induced a peace treaty in September 1905 without any further battles.

Prior to the Russo-Japanese War, countries constructed their battleships with mixed batteries of mainly 152 mm (6-inch), 203 mm (8-inch), 254 mm (10-inch) and 305 mm (12-inch) guns, with the intent that these battleships fight on the battle line in a close-quarter, decisive fleet action. The Battle of Tsushima conclusively demonstrated that battleship speed and big guns[7] with longer ranges were more advantageous in naval battles than mixed batteries of different sizes.[8]

The wireless telegraph had been invented during the last half of the 1890s, and by the turn of the century nearly all major navies were adopting this improved communications technology. Nonetheless Tsushima would be "the first major sea battle in which wireless played any role whatsoever."[9] Alexander Stepanovich Popov of the Naval Warfare Institute had built and demonstrated a wireless telegraphy set in 1900, and equipment from the firm Telefunken in Germany was adopted by the Imperial Russian Navy. In Japan, Professor Shunkichi Kimura was commissioned into the Imperial Navy to develop their own wireless system, and this was in place in many Japanese warships before 1904. Although both sides had early wireless telegraphy, the Russians were using German sets and had difficulties in their use and maintenance, while the Japanese had the advantage of using their own equipment.

Background

Conflict in the Far East

On 8 February 1904 destroyers of the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on the Russian Far East Fleet anchored in Port Arthur; three ships – two battleships and a cruiser – were damaged in the attack. The Russo-Japanese war had thus begun. Japan's first objective was to secure its lines of communication and supply to the Asian mainland, enabling it to conduct a ground war in Manchuria. To achieve this, it was necessary to neutralize Russian naval power in the Far East. At first, the Russian naval forces remained inactive and did not engage the Japanese, who staged unopposed landings in Korea. The Russians were revitalised by the arrival of Admiral Stepan Makarov and were able to achieve some degree of success against the Japanese, but on 13 April Makarov's flagship, the battleship Petropavlovsk struck a mine; Makarov was among the dead.[10] His successors failed to challenge the Japanese Navy, and the Russians were effectively bottled up in their base at Port Arthur.

By May, the Japanese had landed forces on the Liaodong Peninsula and in August began the siege of the naval station. On 9 August, Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft, commander of the 1st Pacific Squadron, was ordered to sortie his fleet to Vladivostok,[11] link up with the Squadron stationed there, and then engage the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in a decisive battle.[12] Both squadrons of the Russian Pacific Fleet would ultimately become dispersed during the battles of the Yellow Sea on 10 August and the Ulsan on 14 August 1904. What remained of Russian naval power would eventually be sunk in Port Arthur.[13]

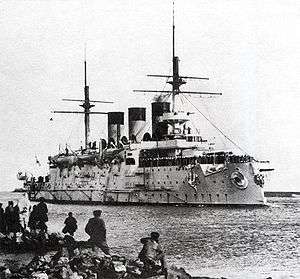

The Second Pacific Squadron

With the inactivity of the First Pacific Squadron after the death of Admiral Makarov and the tightening of the Japanese noose around Port Arthur, the Russians considered sending part of their Baltic Fleet to the Far East. The plan was to relieve Port Arthur by sea, link up with the First Pacific Squadron, overwhelm the Imperial Japanese Navy, and then delay the Japanese advance into Manchuria until Russian reinforcements could arrive via the Trans-Siberian railroad and overwhelm the Japanese land forces in Manchuria. As the situation in the Far East deteriorated, the Tsar (encouraged by his cousin Kaiser Wilhelm II),[14] agreed to the formation of the Second Pacific Squadron.[15] This would consist of five divisions of the Baltic Fleet, including 11 of its 13 battleships. The squadron departed on 15 October 1904 under the command of Admiral Zinovy Rozhestvensky.

The Second Pacific Squadron sailed through the Baltic into the North Sea. The Russians had heard (false) rumours of Japanese torpedo boats operating in the area and were on high alert. In the Dogger Bank incident, the jumpy Russian fleet mistook a group of British fishing boats operating on the Dogger Bank at night for hostile Japanese vessels. The fleet fired upon the small civilian trawlers, killing several British fishermen. In the confusion the Russians even fired upon two of their own vessels, killing some of their own men. The firing continued for twenty minutes before Rozhestvensky ordered firing to cease; greater loss of life was only avoided because the Russian gunnery was highly inaccurate.

The British were outraged by the incident and incredulous that the Russians could mistake a group of fishing trawlers for Japanese warships, thousands of miles from the nearest Japanese port. Britain almost entered the war in support of Japan, with whom it had a mutual defence agreement (but was neutral in the war, as their treaty contained a specific exemption for Japanese action in China and Korea). The Royal Navy sortied and shadowed the Russian fleet while a diplomatic agreement was reached.[15] The Russians were forced to accept responsibility for the incident, compensate the fishermen, disembark officers who were suspected of misconduct to give evidence to an enquiry, and banned from using the Suez Canal. Forced to take a much longer route to the Far East, the Russians sailed around Africa, and by April and May 1905 had anchored at Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina (now Vietnam).

The voyage took several months in rough seas, with difficulty obtaining coal for refuelling – as the warships could not legally enter the ports of neutral nations – and the morale of the crews plummeted. The Russians had been ordered to break the blockade of Port Arthur, but the city had already fallen (on 2 January) by the time they arrived in the Far East. The objective was therefore shifted to linking up with the remaining Russian ships stationed in the port of Vladivostok, before bringing the Japanese fleet to battle.

Tsushima Strait

The Russians could have sailed through any one of three possible straits to enter the Sea of Japan and reach Vladivostok: La Pérouse, Tsugaru, and Tsushima. Admiral Rozhestvensky chose Tsushima in an effort to simplify his route. Admiral Tōgō, based at Busan, also believed Tsushima would be the preferred Russian course. The Tsushima Strait is the body of water eastward of the Tsushima Island group, located midway between the Japanese island of Kyushu and the Korean Peninsula, the shortest and most direct route from Indochina. The other routes would have required the fleet to sail east around Japan. The Japanese Combined Fleet and the Russian Second and Third Pacific Squadrons, sent from the Baltic Sea, would fight in the straits between Korea and Japan near the Tsushima Islands.

Prelude

Because of the 18,000-mile journey, the Russian fleet was in relatively poor condition for battle. Apart from the four newest Borodino-class battleships, Admiral Nebogatov's 3rd Division[16] consisted of older and poorly maintained warships. Overall neither side had a significant maneuverability advantage.[17] The long voyage, combined with a lack of opportunity for maintenance, meant the Russian ships were heavily fouled, significantly reducing their speed.[18] The Japanese ships could sustain 15 knots (28 km/h), but the Russian fleet could reach just 14 knots (26 km/h), and then only in short bursts.[17]

Tōgō achieved "crossing the T" twice. Additionally, there were significant deficiencies in the Russian naval fleet's equipment and training. Russian naval tests with their torpedoes exposed major technological failings.[19] Tōgō's greatest advantage was that of experience, being the only active admiral in any navy with combat experience aboard battleships.[20] (The others were Russian Admirals Oskar Viktorovich Stark, who had been relieved of his command following his humiliating defeat in the Battle of Port Arthur, Admiral Stepan Makarov, killed by a mine off Port Arthur, and Wilgelm Vitgeft, who had been killed in the Battle of the Yellow Sea.)

Battle

Naval tactics

Battleships, cruisers, and other vessels were arranged into divisions, each division being commanded by a Flag Officer (Admiral). At the battle of Tsushima, Admiral Tōgō was the officer commanding in the battleship Mikasa (the other divisions being commanded by Vice Admirals, Rear Admirals, Commodores, Captains and Commanders for the destroyer divisions). Next in line after Mikasa came the battleships Shikishima, Fuji and Asahi. Following them were two armoured cruisers.

Admiral Tōgō, by using reconnaissance and choosing his position well, "secured beyond reasonable hazard his strategic objective of bringing the Russian fleet to battle, irrespective of speeds."[21] When Tōgō decided to execute a turn to port in sequence, he did so to preserve the sequence of his battleline, with the flagship Mikasa still in the lead (which could indicate that Admiral Tōgō wanted his more powerful units to enter action first).

Turning in sequence meant that each ship would turn one after the other whilst still following the ship in front. Effectively each vessel would turn over the same piece of sea (this being the danger in the maneuver as it gives the enemy fleet the opportunity to target that area). Tōgō could have ordered his ships to turn "together", that is, each ship would have made the turn at the same time and reversed course. This maneuver, the same one effected by the French-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar, would be quicker but would have disrupted the sequence of the battleline and caused confusion by altering the battle plans and placing the cruisers in the lead. This was something Tōgō wished to avoid.

First contact

Because the Russians desired to slip undetected into Vladivostok, as they approached Japanese waters they steered outside regular shipping channels to reduce the chance of detection. On the night of 26/27 May 1905 the Russian fleet approached the Tsushima Strait.

In the night, thick fog blanketed the straits, giving the Russians an advantage. At 02:45 Japan Standard Time (JST), the Japanese auxiliary cruiser Shinano Maru observed three lights on what appeared to be a vessel on the distant horizon and closed to investigate. These lights were from the Russian hospital ship Orel, which, in compliance with the rules of war, had continued to burn them.[22] At 04:30, Shinano Maru approached the vessel, noting that she carried no guns and appeared to be an auxiliary. The Orel mistook the Shinano Maru for another Russian vessel and did not attempt to notify the fleet. Instead, she signaled to inform the Japanese ship that there were other Russian vessels nearby. The Shinano Maru then sighted the shapes of ten other Russian ships in the mist. The Russian fleet had been discovered, and any chance of reaching Vladivostok undetected had disappeared.

Wireless telegraphy played an important role from the start. At 04:55, Captain Narukawa of the Shinano Maru sent a message to Admiral Tōgō in Masampo that the "Enemy is in square 203". By 05:00, intercepted wireless signals informed the Russians that they had been discovered and that Japanese scouting cruisers were shadowing them. Admiral Tōgō received his message at 05:05, and immediately began to prepare his battle fleet for a sortie.

Beginning of the battle

At 06:34, before departing with the Combined Fleet, Admiral Tōgō wired a confident message to the navy minister in Tokyo:

In response to the warning that enemy ships have been sighted, the Combined Fleet will immediately commence action and attempt to attack and destroy them. Weather today fine but high waves.[23]

The final sentence of this telegram has become famous in Japanese military history, and has been quoted by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe.[24]

At the same time the entire Japanese fleet put to sea, with Tōgō in his flagship Mikasa leading over 40 vessels to meet the Russians. Meanwhile, the shadowing Japanese scouting vessels sent wireless reports every few minutes as to the formation and course of the Russian fleet. There was mist which reduced visibility and the weather was poor. Wireless gave the Japanese an advantage; in his report on the battle, Admiral Tōgō noted the following:

Though a heavy fog covered the sea, making it impossible to observe anything at a distance of over five miles, [through wireless messaging] all the conditions of the enemy were as clear to us, who were 30 or 40 miles distant, as though they had been under our very eyes.[25]

At 13:40, both fleets sighted each other and prepared to engage. At around 13:55, Tōgō ordered the hoisting of the Z flag, issuing a predetermined announcement to the entire fleet:

The Empire's fate depends on the result of this battle, let every man do his utmost duty.[26]

By 14:45, Tōgō had 'crossed the Russian T'[27] enabling him to fire broadsides, while the Russians could only reply with their forward turrets.[28][29][30]

Daylight action

The Russians sailed from south southwest to north northeast; "continuing to a point of intersection which allowed only their bow guns to bear; enabling him [Tōgō] to throw most of the Russian batteries successively out of bearing." [31] The Japanese fleet steamed from northeast to west, Tōgō ordered the fleet to turn in sequence, which enabled his ships to take the same course as the Russians, although risking each battleship consecutively. Although Tōgō's U-turn was successful, Russian gunnery had proven surprisingly good and the flagship Mikasa was hit 15 times in five minutes. Before the end of the engagement she was struck 15 more times by large caliber shells.[32] Rozhestvensky had only two alternatives, "a charge direct, in line abreast", or to commence "a formal pitched battle." [31] He chose the latter, and at 14:08, the Japanese flagship Mikasa was hit at about 7,000 metres, with the Japanese replying at 6,400 meters. Superior Japanese gunnery then took its toll,[33] with most of the Russian battleships being crippled.

Commander Vladimir Semenoff, a Russian staff officer aboard the flagship Knyaz Suvorov, said "It seemed impossible even to count the number of projectiles striking us. Shells seemed to be pouring upon us incessantly one after another.[34] The steel plates and superstructure on the upper decks were torn to pieces, and the splinters caused many casualties. Iron ladders were crumpled up into rings, guns were literally hurled from their mountings. In addition to this, there was the unusually high temperature and liquid flame of the explosion, which seemed to spread over everything. I actually watched a steel plate catch fire from a burst." [30]

Ninety minutes into the battle, the first warship to be sunk was the Russian battleship Oslyabya from Rozhestvensky's 2nd Battleship division. This was the first time a modern armoured warship had been sunk by gunfire alone.[35]

A direct hit on the Russian battleship Borodino's magazines by the Japanese battleship Fuji caused her to explode, which sent smoke thousands of metres (yards) into the air and trapped all of her crew on board as she sank.[30] Rozhestvensky was knocked out of action by a shell fragment that struck his skull. In the evening, Rear Admiral Nebogatov took over command of the Russian fleet. The Russians lost the battleships Knyaz Suvorov, Oslyabya, Imperator Aleksandr III and Borodino. The Japanese ships suffered only light damage.

Night attacks

At night, around 20:00, 21 destroyers and 37 Japanese torpedo boats were thrown against the Russians. The destroyers attacked from the vanguard while the torpedo boats attacked from the east and south of the Russian fleet. The Japanese were aggressive, continuing their attacks for three hours without a break, as a result during the night, there were a number of collisions between the small craft and Russian warships. The Russians were now dispersed in small groups trying to break northwards. By 23:00, it appeared that the Russians had vanished, but they revealed their positions to their pursuers by switching on their searchlights – ironically, the searchlights had been turned on to spot the attackers. The old battleship Navarin struck a mine and was compelled to stop; she was consequently torpedoed four times and sunk. Out of a crew of 622, only three survived, one to be rescued by the Japanese and the other two by a British merchant ship.

The battleship Sissoi Veliky was badly damaged by a torpedo in the stern, and was scuttled the next day. Two old armoured cruisers – Admiral Nakhimov and Vladimir Monomakh – were badly damaged, the former by a torpedo hit to the bow, the latter by colliding with a Japanese destroyer. They were both scuttled by their crews the next morning, the Admiral Nakhimov off Tsushima Island, where she headed while taking on water. The night attacks had put a great strain on the Russians, as they had lost two battleships and two armoured cruisers, while the Japanese had only lost three torpedo boats.

XGE signal and Russian surrender

During the night action, Tōgō had deployed his torpedo boat destroyers to destroy any remaining enemy vessels, chase down any fleeing warships, and then consolidate his heavy units. At 09:30 on 28 May, what remained of the Russian fleet was sighted heading northwards. Tōgō's battleships proceeded to surround Nebogatov's remaining squadron south of the island of Takeshima and commenced main battery fire at 12,000 meters.[36] Realising that his guns were out ranged by at least one thousand metres (yards) and that he could be destroyed at Tōgō's leisure, Nebogatov ordered the six ships remaining under his command to surrender. XGE, an international signal of surrender, was hoisted; however, the Japanese navy continued to fire as they did not have "surrender" in their code books and had to hastily find one that did. Still under heavy fire, Nebogatov then ordered white table cloths sent up the mastheads, but Tōgō having had a Chinese warship escape him while flying that flag during the 1894 war did not trust them, and continued to fire his main batteries. The Russian cruiser Izumrud then lowered her XGE surrender flag and attempted to flee.[37] Running out of options, Nebogatov ordered the Imperial Japanese Navy flag up the mastheads and all engines stopped.[38] When Japanese flags began showing up in 12-inch gun range finders, Tōgō gave the cease fire and accepted Nebogatov's surrender. Nebogatov surrendered knowing that he could be shot for doing so.[nb 1][30] He said to his men:

You are young, and it is you who will one day retrieve the honour and glory of the Russian Navy. The lives of the two thousand four hundred men in these ships are more important than mine.[30]

Neither Nebogatov nor Rozhestvensky were shot when they returned home to Russia. However, both were placed on trial. Rozhestvensky claimed full responsibility for the fiasco; but as he had been wounded and unconscious during the last part of the battle, the Tsar commuted his death sentence. Nebogatov, having surrendered the fleet at the end of the naval engagement, was imprisoned for several years and eventually pardoned by the Tsar. Both men's reputations were ruined.

Until the evening of 28 May, isolated Russian ships were pursued by the Japanese until almost all were destroyed or captured. Three Russian warships reached Vladivostok. The cruiser Izumrud, which escaped from the Japanese despite being present at Nebogatov's surrender, was scuttled by her crew after running aground near the Siberian coast.

Contributing factors

The Japanese fleets had practised gunnery regularly since the beginning of the war, using sub-calibre adapters in their guns and gaining more experience than the Russians. The Japanese also used mostly high-explosive shells with shimose (melinite), which was designed to explode on contact and wreck the upper structures of ships.[39] The Russians used armour-piercing rounds with small guncotton bursting charges and unreliable fuses.[40] Japanese hits caused more damage to Russian ships relative to Russian hits on Japanese ships, setting the superstructures, the paintwork and the large quantities of coal stored on the decks on fire. (The Russian fleet often bought low-quality coal at sea from merchant vessels on most of their long voyage due to the lack of friendly fuelling ports).

Japanese fire was also more accurate because they were using the latest issued (1903) Barr and Stroud FA3 coincidence rangefinder, which had a range of 6,000 yards (5,500 m), while the Russian battleships were equipped with Liuzhol rangefinders from the 1880s, which only had a range of about 4,000 yards (3,700 m).[41] And finally, by 27 May 1905, Admiral Tōgō and his men had two battleship fleet actions under their belts, which amounted to over four hours of combat experience in battleship-to-battleship combat at Port Arthur and the Yellow Sea[42]

Aftermath

Russian losses

The battle was humiliating for Russia, which lost all its battleships and most of its cruisers and destroyers. The battle effectively ended the Russo-Japanese War in Japan's favour. The Russians lost 4,380 killed and 5,917 captured, including two admirals, with a further 1,862 interned.[43]

Battleships

The Russians lost eleven battleships, including three smaller coastal vessels, either sunk or captured by the Japanese, or scuttled by their crews to prevent capture. Four ships were lost to enemy action during the daylight battle on 27 May: Knyaz Suvorov, Imperator Aleksandr III, Borodino and Oslyabya. Navarin was lost during the night action, on 27–28 May, while the Sissoi Veliky, Admiral Nakhimov and Admiral Ushakov were either scuttled or sunk the next day. Four other battleships, under Rear Admiral Nebogatov, were forced to surrender and would end up as prizes of war. This group consisted of only one modern battleship, Oryol, along with the old battleship Imperator Nikolai I and the two small coastal battleships General Admiral Graf Apraksin and Admiral Seniavin.[44] The small coastal battleship Admiral Ushakov refused to surrender and was scuttled by her crew.[44]

Cruisers

The Russian Navy lost four of its eight cruisers during the battle, three were interned by the Americans, with just one reaching Vladivostok. Vladimir Monomakh and Svetlana were sunk the next day, after the daylight battle. The cruiser Dmitrii Donskoi fought against six Japanese cruisers and survived; however, due to heavy damage she was scuttled. Izumrud ran aground near the Siberian coast.[44] Three Russian protected cruisers, Aurora, Zhemchug, and Oleg escaped to the U.S. naval base at Manila[44] in the then-American-controlled Philippines where they were interned, as the United States was neutral. The armed yacht (classified as a cruiser), Almaz, alone was able to reach Vladivostok.[45]

Destroyers and auxiliaries

Imperial Russia also lost six of its nine destroyers in the battle, had one interned by the Chinese, and the other two escaped to Vladivostok. They were – Buyniy ("Буйный"), Bistriy ("Быстрый"), Bezuprechniy ("Безупречный"), Gromkiy ("Громкий") and Blestyashchiy ("Блестящий") – sunk on 28 May, Byedoviy ("Бедовый") surrendered that day. Bodriy ("Бодрый") was interned in Shanghai; Grosniy ("Грозный") and Braviy ("Бравый") reached Vladivostok.

Of the auxiliaries, Kamchatka, Ural and Rus were sunk on 27 May, Irtuish ran aground on 28 May, Koreya and Svir were interned in Shanghai; Anadyr escaped to Madagascar. The hospital ships Orel and Kostroma were captured; Kostroma was released afterwards.

Japanese losses

The Japanese lost three torpedo boats (Nos. 34, 35 and 69), with 117 men killed and 500 wounded.[43]

Political consequences

Imperial Russia's prestige was badly damaged and the defeat was a blow to the Romanov dynasty. Most of the Russian fleet was lost; the fast armed yacht Almaz (classified as a cruiser of the 2nd rank) and the destroyers Grozny and Bravy were the only Russian ships to reach Vladivostok.[45] In The Guns of August, the American historian and author Barbara Tuchman argued that because Russia's loss destabilized the balance of power in Europe, it emboldened the Central Powers and contributed to their decision to go to war in 1914.

The battle had a profound cultural and political impact upon Japan. It was the first defeat of a European power by an Asian nation in the modern era.[46][47] It also weakened the notion of white superiority that was prevalent in some Western countries.[48] The victory established Japan as the sixth greatest naval power[49] while the Russian navy declined to one barely stronger than that of Austria-Hungary.[49]

In The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles, the British historian Geoffrey Regan argues that the victory bolstered Japan's increasingly aggressive political and military establishment. According to Regan, the lopsided Japanese victory at Tsushima:

...created a legend that was to haunt Japan's leaders for forty years. A British admiral once said, 'It takes three years to build a ship, but 300 years to build a tradition.' Japan thought that the victory had completed this task in a matter of a few years ... It had all been too easy. Looking at Tōgō's victory over one of the world's great powers convinced some Japanese military men that with more ships, and bigger and better ones, similar victories could be won throughout the Pacific. Perhaps no power could resist the Japanese navy, not even Britain and the United States.[43]

Regan also believes the victory contributed to the Japanese road to later disaster, "because the result was so misleading. Certainly the Japanese navy had performed well, but its opponents had been weak, and it was not invincible... Tōgō's victory [helped] set Japan on a path that would eventually lead her" to the Second World War.[43]

Isoroku Yamamoto, the future Japanese admiral who would go on to plan the attack on Pearl Harbor and command the Imperial Japanese Navy through much of the Second World War, served as a junior officer (aboard Nisshin) during the battle and was wounded by Russian gunfire.

Dreadnought arms race

Britain's First Sea Lord, Admiral Fisher, reasoned that the Japanese victory at Tsushima confirmed the importance of large guns and speed for modern battleships;[50][51] in October 1905 the British started the construction of HMS Dreadnought, which upon her launching in 1906 began a naval arms race between Britain and Germany in the years before 1914.[52] The British and Germans were both aware of the potentially devastating consequences of a naval defeat on the scale of Tsushima. Britain needed its battle fleet to protect its empire, and the trade routes vital to its war effort. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, described British Admiral John Jellicoe as "the only man who could lose the war in an afternoon". German naval commanders, for their part, understood the importance Kaiser Wilhelm II attached to his navy and the diplomatic prestige it carried. As a result of caution, the British and German fleets met in only one major action in World War I, the indecisive Battle of Jutland.

Timeline

27 May 1905 (JST)

- 04:45 The Shinano Maru (Japan) locates the Russian Baltic Fleet and sends a wireless signal.

- 05:05 The Japanese Combined Fleet leaves port and sends a wireless signal to Imperial Headquarters: "Today's weather is fine but waves are high. (Japanese: 本日天気晴朗なれども波高し)".

- 13:39 The Japanese Combined Fleet gains visual contact with the Russian Baltic Fleet, and sends up the battle flag.

- 13:55 Distance (Range): 12,000 meters. The Mikasa sends up 'Z' flag. (Z flag's meaning: The Empire's fate depends on the result of this battle, let every man do his utmost duty.).

- 14:05 Distance (Range): 8,000 meters. The Japanese Combined Fleet turns their helm aport (i.e. starts a U-turn).

- 14:07 Distance (Range): 7,000 meters. The Mikasa completes her turn. The Russian Baltic Fleet opens fire with their main batteries.

- 14:10 Distance (Range): 6,400 meters. All Japanese warships complete their turns.

- 14:12 Distance (Range): 5,500 meters. The Mikasa receives her first hit from the Russian guns.

- 14:16 Distance (Range): 4,600 meters. The Japanese Combined Fleet begins concentrating their return fire on the Russian flagship, the Knyaz Suvorov.

- 14:43 The Oslyabya and Knyaz Suvorov are set on fire and fall away from the battle line.

- 14:50 The Imperator Aleksandr III starts turning to the north and attempts to leave the battle line.

- 15:10 The Oslyabya sinks, and the Knyaz Suvorov attempts to withdraw.

- 18:00 The two fleets counterattack each other (distance (range): 6,300 m), and begin exchanging main battery fire again.

- 19:03 The Imperator Aleksandr III sinks.

- 19:20 The Knyaz Suvorov and Borodino sink.

28 May 1905 (JST)

- 09:30 The Japanese Combined Fleet locates the Russian Baltic Fleet again.

- 10:34 Admiral Nebogatov signals "XGE", which is "I surrender" in the International Code of Signals used at the time.

- 10:53 Admiral Tōgō accepts the surrender.

- Crossing the T: Japanese are in white, the Russians in red

- The Knyaz Suvorov, Oslyabya, Imperator Aleksandr III, and Sissoi Veliky breaking off from the main battle

- The first and second Japanese fleets sandwiching the Russian fleet

- The Russian ships fleeing

On film

The 1969 film The Battle of the Japan Sea (日本海大海戦, Nihonkai-DaiKaisen) depicts the battle.

- Title: The Battle of the Japan Sea

- Release date: 1969

- Directed by Seiji Maruyama

- Starring: Toshiro Mifune as the Admiral Tōgō

- Music by Masaru Sato

- Special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya

See also

Notes

- ↑ During Nebogatov's court martial, his defense for surrendering his battle fleet was because his guns were out ranged by the Japanese guns

- ↑ 100 Battles, Decisive Battles that Shaped the World, Dougherty, Martin, J., Parragon, pp. 144–45

- ↑ Sterling, Christopher H. (2008). Military communications: from ancient times to the 21st century. ABC-CLIO. p. 459. ISBN 1-85109-732-5.

The naval battle of Tsushima, the ultimate contest of the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War, was one of the most decisive sea battles in history.

- ↑ Naval War College Press (U.S.), ed. (2009). Joint Operational Warfare Theory and Practice and V. 2, Historical Companion. Government Printing Office. p. V-76. ISBN 1-884733-62-X.

In retrospect, the battle of Tsushima in May 1905 was the last "decisive" naval battle in history.

- ↑ Brown p. 10

- ↑ Semenoff (1907) p. ix

- ↑ Morris, Edmund (2001). Theodore Rex. ISBN 0-394-55509-0.

- ↑ Massie pp. 470–80

- ↑ Semenoff (1907) pp. 124, 135

- ↑ Busch pp. 137–38

- ↑ Sondhaus 2001, p. 188.

- ↑ Forczyk p. 48

- ↑ Forczyk pp. 26, 54

- ↑ Sondhaus 2001, p. 189.

- ↑ Busch p. 214

- 1 2 Sondhaus 2001, p. 190.

- ↑ Forczyk p. 66

- 1 2 Forczyk p. 33

- ↑ Forczyk, p. 32

- ↑ In one such trial, of the seven torpedoes fired, one jammed in the tube, two veered ninety degrees to port, one went ninety degrees to starboard, two kept a steady course but went wide of the mark, and the last went round in circles 'popping up and down like a porpoise', causing panic throughout the fleet." Regan, Geoffrey; The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles, "The Battle of Tsushima 1905", p. 176

- ↑ Forczyk pp. 8, 43, 73 & back cover

- ↑ Mahan p. 456

- ↑ Watts p. 22

- ↑ Translated by Andrew Cobbing in Shiba Ryotaro, Clouds Above the Hill, volume 4, p. 212. Routledge, 2013.

- ↑ "After Terrible GDP Report, Japan Is Getting Ready To Calling A Snap Election". Business Insider. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ↑ Admiral Tōgō's report on the Battle of Tsushima, as published by the Japanese Imperial Naval Headquarters Staff, September 1905; http://www.russojapanesewar.com/togo-aar3.html

- ↑ Koenig, Epic Sea Battles, p. 141.

- ↑ Semenoff (1907) p. 70

- ↑ Mahan pp. 457–58

- ↑ Regan; The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles-The Battle of Tsushima 1905, pp. 176–77

- 1 2 3 4 5 Regan; The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles-The Battle of Tsushima 1905, p. 177

- 1 2 Mahan p. 458

- ↑ Busch pp. 150, 161, 163

- ↑ Sondhaus 2001, p. 191.

- ↑ Semenoff (1907) pp. 62–63

- ↑ Busch pp. 159–160

- ↑ Busch p. 179

- ↑ Busch p. 184

- ↑ Busch p. 186

- ↑ Semenoff (1907) p. 63

- ↑ Semenoff (1907) p. 56

- ↑ Forczyk pp. 56–57

- ↑ Forczyk pp. 43, 73

- 1 2 3 4 Regan; The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles – The Battle of Tsushima 1905, p. 178

- 1 2 3 4 Willmott 2009, p. 118.

- 1 2 Willmott 2009, p. 119.

- ↑ Forczyk back cover

- ↑ Pleshakov p. xvi

- ↑ "the Impact of the Russo-Japanese War in Asia". The American Forum for Global Education. Archived from the original on 2003-01-06. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- 1 2 Sondhaus 2001, p. 192.

- ↑ Massie, pp. 471, 474, 480

- ↑ Busch p. 215

- ↑ The Rivalry of Germany and England, Edward Raymond Turner, The Sewanee Review, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Apr., 1913), pp. 129–17

References

- Brown, David (1990). Warship Losses of World War Two. Arms and Armor Press, Great Britain. ISBN 0-85368-802-8.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–1905. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Evans, David C; Peattie, Mark R (1997). Kaigun: strategy, tactics, and technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Koenig, William (1977). Epic Sea Battles (2004 revised ed.). London: Octopus Publishing Group Ltd. ISBN 0-7537-1062-5.

- Willmott, H. P. (2009). The Last Century of Sea Power: From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894–1922, Volume 1. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-41521-477-7.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1906). Reflections, Historic and Other, Suggested by the Battle of the Japan Sea. (Article) US Naval Proceedings magazine, June 1906, Volume XXXVI, No. 2; US Naval Institute, Heritage Collection.

- Massie, Robert K. (1991). Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War. Random House, NY. ISBN 0-394-52833-6.

- Pleshakov, Constantine (2002). The Tsar's Last Armada; The Epic Voyage to the Battle of Tsushima. ISBN 0-465-05792-6.

- Regan, Geoffrey (1992) 'The Battle of Tsushima 1905' in The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles, Guinness Publishing.

- Semenoff, Vladimir Captain (1907). The Battle of Tsushima. Translated by Captain A. B. Lindsay; Preface by Sir George Sydenham Clarke, G.C.M.G., F.R.S., John Murray, London, second edition 1907.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-41521-477-7.

- Stille, Mark (2016). The Imperial Japanese Navy of the Russo-Japanese War. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 1-47281-121-6.

- Willmott, H. P. (2009). The Last Century of Sea Power: From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894–1922, Volume 1. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-25300-356-3.

- Watts, Anthony J. The Imperial Russian Navy. Arms and Armour Press, Villiers House, 41–47 Strand, London, 1990. ISBN 0-85368-912-1.

Further reading

- Busch, Noel F. (1969). The Emperor's Sword: Japan vs. Russia in the Battle of Tsushima. New York: Funk & Wagnall’s.

- Connaughton, Richard M. (1991). The War of the Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear: A Military History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-5. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-07143-7.

- Corbett, Julian (1994). Maritime Operations In The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. ISBN 1-55750-129-7.

- Hailey, Foster; Milton Lancelot (1964). Clear for Action: The Photographic Story of Modern Naval Combat, 1898–1964. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce.

- Hough, Richard Alexander (1960). The Fleet That Had to Die. New York: Ballantine Paperbacks.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Dieter Jung; Peter Mickel (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Novikoff-Priboy, A (1937). Tsushima. A.A. Knopf.

- Olender, Piotr (2010). Russo-Japanese Naval War 1904–1905, Vol. 2, Battle of Tsushima. Sandomierz, Poland: Stratus s.c. ISBN 978-83-61421-02-3.

- Seager, Robert (1977). Alfred Thayer Mahan: The Man And His Letters. ISBN 0-87021-359-8.

- Semenoff, Vladimir (1910). Rasplata (The Reckoning). London: John Murray.

- Semenoff, Vladimir (1912). The Battle of Tsushima. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co.

- Thiess, Frank (1937). The Voyage of Forgotten Men. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merill Company.

- Tikowara, Hesibo; Grant, R. (1907). Before Port Arthur in a Destroyer, The Personal Diary of a Japanese Naval Officer. London: John Murray.

- Tomitch, V. M. (1968). Warships of the Imperial Russian Navy. BT Publishers.

- Warner, Denis and Peggy (1975). The Tide at Sunrise. A History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.

- Wilson, H. W. (1969). Battleships in Action (1999 revised ed.). Scholarly Press. ISBN 0-85177-642-6.

- Woodward, David (1966). The Russians at Sea: A History of the Russian Navy. New York: Praeger Publishers.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Tsushima. |

- History.com— This Day In History: The Battle of Tsushima Strait

- Battlefleet 1900—Free naval wargame rules covering the pre-dreadnought era, including the Russo-Japanese War.

- Russojapanesewar.com—Contains a complete order of battle of both fleets. It also contains Admiral Tōgō's post-battle report and the account of Russian ensign Sememov.