First Battle of Lexington

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The First Battle of Lexington, also known as the Battle of the Hemp Bales or the Siege of Lexington, was an engagement of the American Civil War, occurring from September 12 to September 20, 1861,[3] between the Union Army and the pro-Confederate Missouri State Guard, in Lexington, the county seat of Lafayette County, Missouri. The State Guard's victory in this battle bolstered the already-considerable Southern sentiment in the area, and briefly consolidated Missouri State Guard control of the Missouri River Valley in western Missouri.

This engagement should not be confused with the Second Battle of Lexington, which was fought on October 19, 1864, and also resulted in a Southern victory.

Prelude

Prior to the Civil War, Lexington was an agricultural town of over 4,000 residents[4] and county seat of Lafayette County, occupying a position of considerable local importance on the Missouri River in west-central Missouri. Hemp (used for rope production), tobacco, coal and cattle all contributed to the town's wealth, as did the river trade. Many residents were slaveowners, like those of adjacent counties; slaves comprised 31.7% of the Lafayette County population.[5]

Following the battle at Boonville in June 1861, Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon ordered the 5th Regiment of the United States Reserve Corps to occupy Lexington. The regiment was composed primarily of Germans from St. Louis and it had participated in the Camp Jackson Affair. Arriving on the steamer White Cloud on July 9, they were commanded by Colonel Charles G. Stifel. Stifel's second in command was Lt. Col. Robert White, who was often the primary point of contact with the local civilians. Stifel selected the defunct Masonic College as his headquarters and the soldiers began entrenching and fortifying the position.[6]

Stifel's command began scouting, and securing or destroying boats that could be used to cross the river. They also collected about 200 kegs of gunpowder, 33 muskets, and two 6-pounder cannons from the area. The cannons were placed under the charge of Charles M. Pirner. Several local home guard companies were raised and placed under the command of Major Frederick W. Becker.[7]

In mid-August the 90-day enlistments of Stifel's regiment were expiring and they were to return to St. Louis. Lt. Col. Robert White had been organizing a new regiment locally, but left for several weeks. During this time Major Becker had command of the post. Meanwhile, on the Southern side, self-styled Colonel Henry L. Routt of Clay County was attempting to raise a regiment in the area and had collected around a thousand men. Routt had led the force that seized the Liberty Arsenal in April.[8]

Col. Routt arrested several prominent Union men, including former Missouri governor Austin A. King and surrounded the post. He demanded Becker's surrender but this was refused. One night, two of Becker's men, Charles and Gustave Pirner tested some rounds they had fabricated for two mortars that had come into their possession. With one of the mortars they lobbed three shells into Routt's encampment, causing a panic but no real damage. Later, learning of the approach of Col. Thomas A. Marshall's 1st Illinois cavalry, Routt withdrew from the area. Lt. Col. Robert White returned at the end of August and briefly assumed command of the post from Becker until the Illinois cavalry arrived a few days later. White resumed organization of the 14th Home Guard Regiment.[9]

Following their victory at Wilson's Creek on August 10, the main body of the pro-Confederate Missouri State Guard under Maj. Gen. Sterling Price marched toward the Missouri-Kansas border with around 7,000 men to repel incursions by Lane's Kansas Brigade. On September 2, the Guard drove away Lane's Kansans in the Battle of Dry Wood Creek, sending them back beyond Fort Scott. Price then turned north along the border and toward Lexington to break Federal control of the Missouri River and to gather recruits from both sides of the river. As Price proceeded he collected recruits, including Col. Routt and several hundred of his men then at Index in Cass County.[10]

Federal reinforcements arrived in Lexington on September 4--the 13th Missouri Infantry commanded by Col. Everett Peabody and a battalion of the United States Reserve Corps under Maj. Robert T. Van Horn. To prevent rebel Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson from obtaining any funds from local banks, Gen. John C. Frémont gave orders to impound their funds. On September 7, Col. Marshall removed approximately $1,000,000 from the Farmers' Bank in Lexington while Col. Peabody was dispatched to Warrensburg to do the same there. On arriving in Warrensburg, Peabody's detachment found itself in Price's path and made a hasty retreat back to Lexington.[11]

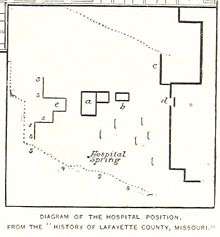

Finally, on September 10, Col. James A. Mulligan arrived to take command with his 23rd Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment known as the "Irish Brigade" and a detachment of the 27th Missouri Mounted Infantry under Lt. Col. Benjamin W. Grover.[12] On September 11, the 13th Missouri Infantry and Van Horn's battalion arrived back in Lexington.[4] Mulligan now commanded 3,500 men, and quickly proceeded to construct extensive fortifications around the town's Masonic College, cutting down trees to make lines of fire and erecting earthworks around the dormitory and classroom buildings. His superiors dispatched further reinforcements under Samuel D. Sturgis, with which Mulligan hoped to hold his enlarged position, but they were ambushed by pro-Confederate forces (alerted by a secessionist telegraph tapper) and compelled to retreat.[13]

Battle

Opening round

Price and his army arrived before Lexington on September 11, 1861. Skirmishing began the morning of September 12 when two Federal companies posted behind hemp shocks along a hill opposed Price's cavalry advance. Price pulled back several miles to Garrison creek to await his artillery and infantry. With their arrival in the afternoon, he resumed the advance along a more westerly course, eventually intercepting the Independence Road.[14] Mulligan dispatched four companies of the 13th Missouri Infantry (USA), and the two companies of Van Horn's United States Reserve Battalion to oppose this movement. They battled Price's advance elements among the tombstones in Machpelah Cemetery south of town, hoping to buy time for the rest of Mulligan's men to complete their defensive preparations.[15] Price's artillery deployed and, along with the growing numbers of attackers, dislodged the defenders and forced them back to the safety of their fortifications.[16]

Price pursued the fleeing defenders and deployed Guibor and Bledsoe's batteries to shell the Federal fortifications at the college. Three Federal artillery pieces replied, destroying one of Guibor's caissons near the end of the exchange. The two and a half hour artillery duel diminished the State Guard's ammunition. Much of the ordnance supply train had been left at Osceola.[17] This development combined with the redoubtable nature of the Union fortifications to render any further assault impractical.[15]

Having bottled the Union forces up in Lexington, Price decided to await his ammunition wagons, other supplies and reinforcements before assaulting his opponent. "It is unnecessary to kill off the boys here," said he; "patience will give us what we want."[18] Accordingly, he ordered his infantry to fall back to the county fairgrounds.

By September 18, Price had determined to order a new assault. The State Guard advanced under heavy Union artillery fire, pushing the enemy back into their inner works. Price's cannon responded to Mulligan's with nine hours of bombardment, utilizing heated shot in their endeavor to set fire to the Masonic College and other Federal positions.[18] Mulligan stationed a youth in the attic of the college's main building, who was able to remove all incoming rounds before they could set the building ablaze.[15]

The Anderson house

|

Anderson House and Lexington Battlefield | |

Anderson House, a Union hospital, was attacked by Confederates during the battle | |

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by 10th, 15th, Utah and Wood Sts., and Missouri Pacific RR, Lexington, Missouri |

|---|---|

| Area | 0 acres (0 ha) |

| Built | 1853 |

| Architectural style | Federal |

| NRHP Reference # | 69000110[19] |

| Added to NRHP | June 4, 1969 |

Once described by a local newspaper as "...the largest and best arranged dwelling house west of St. Louis,"[20] the Anderson House was a three-story, Greek Revival style house constructed by Oliver Anderson, a prominent Lexington manufacturer. Sometime around July 1861, the Anderson family was evicted from their home, which lay adjacent to Col. Mulligan's fortifications, and the Union garrison established a hospital there.[21]

At the start of the Battle of Lexington, over a hundred sick or wounded Union soldiers occupied the Anderson House hospital. Medical care was entrusted to a surgeon named Dr. Cooley, while Father Butler, Chaplain of the 23rd Illinois, provided for the spiritual needs of the soldiers.[15]

Because of its strategic significance, General Thomas Harris of Price's command ordered soldiers from his 2nd Division (MSG) to capture the house on September 18. Shocked at what he considered a violation of the Laws of War, Col. Mulligan ordered the structure to be retaken. Company B, 23rd Illinois, Company B, 13th Missouri, and volunteers from the 1st Illinois Cavalry charged from the Union lines and recaptured the house, suffering heavy casualties in the process. Harris’s troops recaptured the hospital later that day, and it remained in State Guard hands thereafter.[15]

The most controversial incident of the battle would occur during the Federal assault on the Anderson house, when Union troops summarily executed three State Guard soldiers at the base of the grand staircase in the main hall. The Southerners claimed the men had already surrendered, and should have been treated as prisoners of war. The Federal troops, who had sustained numerous casualties in retaking the residence, considered the prisoners to have been in violation of the Laws of War for having attacked a hospital in the first place.

The Anderson home was heavily damaged by cannon and rifle projectiles, with many of the holes still visible both inside and outside the house (which is now a museum) today.

The Anderson House and Lexington Battlefield was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.[19]

Preparing for the final assault

On September 19, the State Guard consolidated its positions, kept the Federals under heavy artillery fire, and prepared for their final attack. One problem faced by the defenders was a chronic lack of water; wells within the Union lines had gone dry, and State Guard sharpshooters were able to cover a nearby spring, picking off any man who endeavored to approach it. Surmising that a woman might succeed where his men had failed, Mulligan sent a female to the spring. Price's troops held their fire, and even permitted her to take a few canteens of water back to the beleaguered Federals.[23] This tiny gesture, however, could not solve the ever-increasing crisis of thirst among the Union garrison, which would contribute to their ultimate undoing.

General Price had established his headquarters in Lexington in a bank building at 926 Main Street on September 18, 1861, located across the street from the Lafayette County Courthouse. During the Battle of Lexington, Price directed State Guard operations from a room on the second floor. On the following day a cannonball, probably fired from Captain Hiram Bledsoe’s State Guard Battery, struck the courthouse only about one hundred yards from General Price’s headquarters.[15] According to accounts dating from 1920, the ball did not originally lodge in the column, but fell out and was recovered by a collector. Decades after the battle the then elderly gentleman signed an affidavit with his story, and gave the cannonball to County Commissioners who had the ball screwed onto a two-foot iron rod embedded in the column for the purpose.[24][25][26]

On the evening of September 19, soldiers of Brig. Gen. Thomas A. Harris's 2nd Division (State Guard) began using hemp bales seized from nearby warehouses to construct a moveable breastwork facing the Union entrenchment. These bales were all soaked in river water overnight, to render them impervious to any heated rounds fired from the Federal guns. Harris's plan was for his troops to roll the bales up the hill the following day, using them for cover as they advanced close enough to the Union garrison for a final charge. The hemp bale line started in the vicinity of the Anderson house, extending north along the hillside for about 200 yards. In many places the hemp bales were stacked two high to provide additional protection.[15]

Deployment of the hemp bales

Early on the morning of September 20, Harris's men advanced behind his mobile breastworks. As the fighting progressed, State Guardsmen from other divisions joined Harris's men behind the hemp bales, increasing the amount of fire directed toward the Union garrison. Although the Union defenders poured red-hot cannon shot into the advancing bales, their soaking in the Missouri River the previous night had given them the desired immunity to the Federal shells. By early afternoon, the rolling fortification had advanced close enough for the Southerners to take the Union works in a final rush. Mulligan requested surrender terms after noon, and by 2:00 p.m. his men had vacated their trenches and stacked their arms.

Many years later, in his book The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Southern president Jefferson Davis opined that "The expedient of the bales of hemp was a brilliant conception, not unlike that which made Tarik, the Saracen warrior, immortal, and gave his name to the northern pillar of Hercules."[27]

Aftermath

Casualties were relatively low because the battle was largely fought from protective positions. Price claimed a loss of only 25 men killed and 72 wounded in his official report. However, a study of his subordinates' after-action reports reveals a total of at least 30 killed and 120 wounded. This would not include any civilians or recruits who had not yet enrolled but joined the fighting.[2] The Federals lost 39 killed and 120 wounded.[18] The relatively light casualties may be attributed to Mulligan's excellent entrenchments and Harris's hemp-bale inspiration; however, the entire Union garrison was taken prisoner.

The surrendered Union soldiers were compelled to listen to a speech by deposed pro-Confederate Missouri governor Claiborne F. Jackson, who upbraided them for entering his state without invitation and waging war upon its citizens.[28] The Federals were then paroled by General Price, with the notable exception of Colonel Mulligan, who refused parole. Price was reportedly so impressed by the Federal commander's demeanor and conduct during and after the battle that he offered Mulligan his own horse and buggy, and ordered him safely escorted to Union lines. Mulligan was later mortally wounded at the Second Battle of Kernstown near Winchester, Virginia on July 24, 1864.

Among the casualties at the First Battle of Lexington was Lt. Col. Benjamin W. Grover, commanding the 27th Missouri Mounted Infantry, who was wounded by a musket ball in the thigh. He succumbed to his wound October 31, 1861.[29]

Following the surrender at Lexington, Fremont and Price negotiated an exchange cartel. The Camp Jackson parolees were exchanged for a portion of Mulligan's command. This worked smoothly for the officers who were specifically named, but not for all of the Federal enlisted men. Some enlisted men were ordered back into Federal service without proper exchange, and moved to different theaters. Several were captured at Shiloh and were recognized and executed for violating their parole.[30]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Battle of Lexington, Missouri. |

Notes

- 1 2 National Park Service battle description

- 1 2 3 Wood, p. 117

- ↑ Wood, p. 38. Skirmishing and first push were on Sept. 12, not Sept. 13. Discrepancy is due to a timeline error in Price's report.

- 1 2 Gifford, Douglas L., Lexington Battlefield Guide, Instantpublisher (self-published), 2004, page 8.

- ↑ 1860 United States Census

- ↑ Wood, p. 18-21.

- ↑ Wood, p. 21-22.

- ↑ Wood, p. 25-26.

- ↑ Wood, p. 26-27.

- ↑ Wood, pp 30-34

- ↑ Wood, pp. 27-28, 35-36

- ↑ MHR Vol. 8, Iss 1, p. 20

- ↑ http://cw-chronicles.com/anecdotes/?p=77. Retrieved on July 29, 2008.

- ↑ Wood, pp. 38-40

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VisitLexington.com Archived July 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., Retrieved on July 27, 2008.

- ↑ Wood, pp. 40-42

- ↑ Wood, pp. 43-45

- 1 2 3 Missouri State Parks. Retrieved on July 27, 2008.

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Lexington Weekly Express, September 14, 1853. Obtained from http://www.mostateparks.com/lexington/andhouse.htm. Retrieved on July 27, 2008.

- ↑ Martha L. Kusiak (April 1969). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Anderson House and Lexington Battlefield" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2017-01-01. (includes 16 photographs from 1991)

- ↑ Robert Underwood Johnson; Clarence Clough Buel (1888). Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: Being for the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers : Based Upon "The Century War Series". I. Century Company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Missouri in the Civil War, Vol. 9, Ch. 7. Retrieved on July 29, 2008.

- ↑ Slusher, p. 25

- ↑ "A Cannonball, a Calaboose, and Counte Basie", tour brochure, 2013

- ↑ Lexington Advertiser-News, June 3, 1970

- ↑ Davis, Jefferson, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Publication date unknown, pg. 432. Retrieved on July 27, 2008.

- ↑ Harpers Weekly, October 19, 1861, pg. 658. Taken from http://www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/civil-war/1861/october/colonel-mulligan.htm. Retrieved on July 27, 2008.

- ↑ Gifford, Douglas L., Lexington Battlefield Guide, Instantpublisher (self-published), 2004, pg. 46.

- ↑ Wood, p. 123.

References

- The Battle of Lexington, 1861 Firsthand accounts of the battle, including official reports from both commanders. (Archived from the original on May 2, 2007)

- Lexington Historical Society (1903). The Battle of Lexington, Fought in and About the City of Lexington, Missouri on September 18, 19 and 20th, 1861. The Intelligencer Printing Company.

- Wood, Larry (2014). The Siege of Lexington Missouri: The battle of the Hemp Bales. The History Press.

- Slusher, Roger E. & Lexington Historical Association (2013). Lexington (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing.

- Lexington Battlefield Guide (Archived from the original on July 26, 2008)

- National Park Service battle description

- CWSAC Report Update

Further reading

- Castel, Albert (1993) [1st pub. 1968]. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West (Louisiana pbk. ed.). Baton Rouge; London: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1854-0. LCCN 68-21804.

Contemporary sketches

From Harpers Weekly magazine:

- "The Battle of Lexington, Missouri, from sketches by a Western correspondent"

- "Charge of the Irish Regiment over the Breast-Works at Lexington, Missouri"

- "Portrait of Colonel Mulligan"

- "The Rebel Ex-Governor Jackson, of Missouri, addressing Colonel Mulligan's troops after the surrender at Lexington"

Coordinates: 39°11′29″N 93°52′43″W / 39.1915°N 93.878636°W