Battle of Wuhan

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

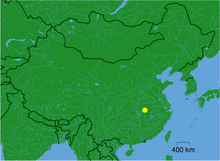

The Battle of Wuhan, popularly known to the Chinese as the Defense of Wuhan, and to the Japanese as the Capture of Wuhan, was a large-scale battle of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Engagements took place across vast areas of Anhui, Henan, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, and Hubei provinces over a period of four and a half months. This battle was the longest, largest and arguably the most significant battle in the early stages of the Second Sino-Japanese War. More than one million National Revolutionary Army troops of the 5th and 9th Military Regions were gathered under the personal leadership of Chiang Kai-shek himself, defending Wuhan from the Central China Area Army of the Imperial Japanese Army led by IJA General Shunroku Hata. Chinese forces were also supported by the Soviet Volunteer Group, a group of volunteer pilots from the Soviet Air Forces.

Although the battle ended with the eventual capture of Wuhan by Japanese forces, it resulted in heavy casualties for both sides, as high as 540,000 by some estimates.[2]

Background

On 7 July 1937, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) launched a full-scale invasion of China. With the onset of the war, Beijing and Tianjin fell to the Japanese in less than one month, which exposed the entire North China Plain to the Japanese Army. On 12 November, the Japanese Army captured Shanghai, threatening Nanjing. The Chinese government was thus forced to transfer its capital to Chongqing.

However, with the fall of three major Chinese cities (Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai), there was a large number of refugees fleeing the fighting in addition to the governmental facilities and war supplies that needed to be transferred to Chongqing. Due to inadequacies in the transport systems, the government was unable to complete the transfer. Wuhan thus became the de facto capital of the Republic of China, due to its strong industrial, economic and cultural foundations. Assistance from the USSR provided additional military and technical resources, including the Soviet Volunteer Group.

On the Japanese side, the IJA forces were drained due to the large number and extent of military operations and campaigns since the beginning of the invasion. Reinforcements were thus dispatched to boost forces in the area, but this placed a considerable strain on the Japanese peacetime economy. This caused then-Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe to reassemble his Cabinet in 1938 as well as to introduce the National Mobilization Law on 5 May that year, moving Japan into a wartime economic state.

Although the realisation of the wartime economy slowed the speed at which Japan's treasury was going bankrupt, it was not possible to continue as such for an extended period of time, especially taking into account concerns regarding the military power of the Soviet Union. The Japanese government thus wished to force the Chinese side into submission quickly in order to gather resources so as to put into place its plan of expansion towards the north and south. As the Japanese Emperor Hirohito said at a meeting before the Battle of Wuhan began, it was necessary to deliver a final, fatal blow to the Nationalist government and force China into surrender. He was unwilling to see "the legions of the Empire tied down in China". Thus, Japan threw in everything it had going into the Battle of Wuhan. According to Japanese documents discovered after the war, "the Army put in its maximum effort for the battle at Hankou (a part of Wuhan) and there is no room for flexibility". Even the single division left in Japan itself was put on standby to assist the forces at Wuhan if necessary.

Importance of Wuhan

Wuhan, located halfway up the Yangtze River, was the second largest city at the time with a population of two million.[3] The city was divided by the Yangtze River and Hanshui into three regions: Wuchang, Hankou and Hanyang. Wuchang was the political center, Hankou was a commercial district while Hanyang was the industrial estate. After the completion of the Yuehan Railway, the importance of Wuhan as a major transportation hub in inland China was further established. It also served as an important transit point for external aid moving inland from the ports in the south.

After the Japanese capture of Nanjing, although the Nationalist government officially moved to Chongqing, the bulk of government agencies and military command headquarters were located in Wuhan. Wuhan thus became the de facto wartime capital at the onset of the engagements in Wuhan. The Chinese war effort was thus focused on protecting Wuhan from being occupied by the Japanese. The Japanese government and the headquarters of the China Expeditionary Force therefore predicted that the fall of Wuhan would lead to the end of Chinese resistance.[4]

As a result of the Second United Front, the first People's Political Council was opened in Hankou on 6 July 1938, and the New Fourth Army was established on 25 December 1937 in Hankou with a strength of around 10 thousand.

Preparations for the battle

On 13 December 1937, the Military Affairs Commission (MAC) set the battle plan for the defense of Wuhan. After the loss of Xuzhou, approximately 130 divisions of 50 armies were redeployed as well as around 200 planes and 40 ships and boats of different kinds, totalling more than 1 million men. The MAC made use of the favourable terrain of the Dabie Mountains, Poyang Lake, and the Yangtze River to organise its defense around the city. The commander of the 5th Military Region, Li Zongren (Bai Chongxi acting from mid-July to mid-September) was put in charge of 23 armies for defenses north of the Yangtze, while the commander of the 9th Military Region, Chen Cheng, was in charge of 27 armies for defenses south of the Yangtze. Meanwhile, the 1st Military Region west of the Zhengzhou-Xinyang section of the Pinghan Railway was tasked with protecting the flank should Japanese units in northern China from moving down south to aid the Japanese offensive. The 3rd Military Region at the southern bank of the Yangtze between Wuhu and Anqing in Anhui province and east of Nanchang in Jiangxi province was to hold off Japanese units if they were to circle back towards the Yuehan Railway by way of the Zhegan Railway.

After the Japanese occupied Xuzhou in May 1938, they sought to actively expand the scale of the invasion. The IJA decided to send a vanguard to first occupy Anqing for use as a forward base for an attack on Wuhan, then for its main force to attack the area north of the Dabie Mountains moving along the Huai River, eventually occupying Wuhan by way of the Wusheng Pass. After that, another detachment would move west along the Yangtze. However, due to the Yellow River flood, the IJA was forced to abandon the plan of attacking along the Huai, and decided to attack along both banks of the Yangtze instead. On 4 May, the commander of the IJA forces, Shunroku Hata, organised approximately 350,000 men of the Second and Eleventh Armies for the fighting in and around Wuhan. Under him, Yasuji Okamura commanded 5 and a half divisions of the Eleventh Army along both banks of the Yangtze in the main assault on Wuhan while Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni commanded 4 and a half divisions of the Second Army along the northern foot of the Dabie Mountains to assist the assault. These forces were augmented by 120 ships of the Third Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy under Koshirō Oikawa, more than 500 planes of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service as well as five divisions of Japanese forces from the Central China Area Army to guard the areas in and around Shanghai, Beijing, Hangzhou, and other important cities, thus protecting the back of the Japanese forces and completing the preparation for the battle.

Prelude

The Battle of Wuhan was preceded by a Japanese air strike on 18 February 1938.[5][6] It was known as the "2.18 Air Battle" and ended with Chinese forces repelling the attack.

On 24 March, the Diet of Japan passed the National Mobilization Law that authorized unlimited funding of war. As part of the law, the National Service Draft Ordinance also allowed the conscription of civilians.

On 29 April, the Japanese air force launched major air strikes on Wuhan to celebrate Emperor Hirohito's birthday.[7][8] The Chinese, with prior intelligence, were well prepared. This battle was known as the "4.29 Air Battle" and was one of the most intense air battles of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Chinese air force shot down 21 Japanese planes at a loss of 12 of their own.[9]

After the fall of Xuzhou in May 1938, the Japanese planned an extensive invasion of Hankou and the takeover of Wuhan, intending to destroy the main force of the National Revolutionary Army. The Chinese, on the other hand, were building up defenses around Wuhan. They managed to gather more than one million troops, around 200 planes, and 30 naval ships.[10] They also set up an advance defense line in Henan to delay the Japanese offensive at Xuzhou. However, due to the disparity in Chinese and Japanese troop strength, this line of defense collapsed quickly.

In an attempt to win more time for the preparation of the defense of Wuhan, the Chinese opened up the dikes of the Yellow River in Huayuankou, Zhengzhou on 9 June. The flood, now known as the 1938 Yellow River flood, forced the Japanese to delay their attack on Wuhan. However, it also caused around 500,000 to 900,000 civilian deaths, flooding many cities in the north of China.[11]

Major engagements

South of the Yangtze River

On 13 June, the Japanese made a naval landing and captured Anqing[12], signalling the onset of the Battle of Wuhan. On the southern bank of the Yangtze River, the Chinese 9th Military Region stationed one regiment west of Poyang Lake, and another regiment around Jiujiang. On 29 June, the Japanese naval fleet passed through the Madang sluice. The main force of the Japanese 11th Army attacked along the southern shore of the river. The Japanese Namita detachment landed east of Jiujiang on 23 July.

The Chinese tried to resist the attack, but they could not repel the landing force of the Japanese 106th Division from capturing Jiujiang on the 26th. The Namita detachment moved westward along the river, landing northeast of Ruichang on 10 August and mounting an assault on the city. The defending NRA 2nd Corps were reinforced by the 32nd Group Army and was initially able to halt the Japanese attack. However, when the Japanese 9th Division entered the frame, the Chinese defenders were exhausted and Ruichang was captured on the 24th.

The 9th Division and the Namita detachment continued to move along the river, while the 27th Division invaded Ruoxi at the same time. The Chinese 30th and 18th Corps resisted along the Ruichang-Ruoxi Road and the surrounding area, resulting in a stalemate for more than a month until the Japanese 27th Division captured Ruoxi on 5 October. The Japanese forces then turned to strike northeast, capturing Xintanpu in Hubei on the 18th and then moving towards Dazhi.

In the meantime, other Japanese forces and the supporting river fleet continued their advance westwards along the Yangtze, encountering resistance from the defending Chinese 31st Army and 32nd Group Army west of Ruichang. When the town of Madang and Fujin Mountain, both in Yangxin County, were captured, the Chinese 2nd Corps deployed the 6th, 56th, 75th and 98th Armies along with the 30th Group Army to strengthen the defense of the Jiangxi region. The battle continued until 22 October when the Chinese lost other towns in Yangxin county, Dazhi and Hubei province. The Japanese 9th Division and Namita detachment were now approaching Wuchang.

Wanjialing

While the Japanese Army attacked Ruichang, the 106th Division moved along the Nanxun Railway (now known as Nanchang-Jiujiang) on the south side. The defending Chinese 4th Army, 8th Group Army and 29th Group Army relied on the advantageous terrain of Lushan and north of Nanxun Railway to resist. As a result, the Japanese offensive suffered a setback. On 20 August, the Japanese 101st Division crossed the Poyang Lake from Hukou County to reinforce the 106th Division, breaching the Chinese 25th Army's defensive line and capturing Xinzhi. They then attempted to occupy De'an County and Nanchang together with the 106th Division to protect the southern flank of the Japanese Army which was advancing westward. Xue Yue, the commander-in-chief of the Chinese 1st Corps, used the 4th, 29th, 66th, and 74th Armies to link with the 25th Army and engage the Japanese in a fierce battle at Madang and north of De'an, throwing the battle into a stalemate.

Towards the end of September, 4 regiments of the Japanese 106th Division circled into the Wanjialing region, west of De'an. Xue Yue commanded the 4th, 66th, and 77th Armies to flank the Japanese. The 27th Division of the Japanese Army attempted to reinforce the position but were ambushed and repulsed by the Chinese 32nd Army led by Shang Zhen in Baisui Street, west of Wanjialing. On 7 October, the Chinese Army mounted a final large-scale assault to encircle the Japanese troops. The fierce battle continued for three days, and all Japanese counter-attacks were repelled by the Chinese.

By 10 October, the 106th Division as well as the 9th, 27th, and 101st Divisions which had gone to reinforce the 106th had all suffered heavy casualties. The Aoki, Ikeda, Kijima, and Tsuda brigades were also annihilated in the encirclement. With Japanese forces in the area losing combat command capabilities, hundreds of officers were airdropped into the area. Of the four Japanese divisions which had gone into the battle, only around 1,500 men made it out of the encirclement. This great victory was later named the Victory of Wanjialing.

After the war, in the year 2000, Japanese military historians admitted the heavy damages that the 9th, 27th, 101st and 106th Divisions and their subordinate units had suffered during the Battle of Wanjialing, multiplying the number of war dead honoured in Japanese shrines. It was also said that the damages were not admitted during the war in order to maintain public morale and confidence in the war effort.

North of the Yangtze River

In Shandong, 1,000 soldiers under Shi Yousan, who had defected multiple times and was currently independent, occupied Jinan and held it for a few days. Guerrillas also held Yantai for a short period of time. The area east of Changzhou all the way to Shanghai was controlled by another non-government Chinese force led by Dai Li, employing guerrilla tactics in the suburbs of Shanghai and across the Huangpu River. This force was made up of secret society members of the Green Gang and the Tiandihui, killing spies and traitors. They lost more than 100 men during their operations. On 13 August, members of this force snuck into the Japanese air base at Hongqiao, raising a Chinese flag.

While these factions were active, the Japanese 6th Division breached the defensive lines of Chinese 31st and 68th Army on 24 July and captured Taihu, Susong, and Huangmei counties on 3 August. As the Japanese continued to move westward, the Chinese 4th Corps of the 5th Military Region deployed their main force in Guangji, Hubei and Tianjia Town to intercept the Japanese offensive. The 11th Group Army and the 68th Army were ordered to form a line of defense in Huangmei county, while the 21st and 29th Group Army, as well as the 26th Army, moved south to flank the Japanese.

The Chinese recaptured Taihu on 27 August and Susong on 28 August. However, with Japanese reinforcements arriving on 30 August, the 11th Group Army and the 68th Army were unsuccessful in their counteroffensives. They retreated to the Guangji region to continue to resist the Japanese forces along with the 26th, 55th, and 86th Armies. The 4th Army Group ordered the 21st and 29th Group Armies to flank the Japanese from northeast of Huangmei, but they were unable to stop the Japanese advance. Guangji was then captured on 6 September. On 8 September, Guangji was recovered by the 4th Corps but Wuxue was lost on that same day.

The Japanese Army then lay siege to Tianjia Town Fort. The 4th Corps sent the 2nd Army to reinforce the 87th Army, and the 26th, 48th, and 86th Armies to flank the Japanese. However, they were beaten back by the battle-hardened Japanese who had greater firepower and suffered many casualties. The Tianjia Town Fort was captured on the 29th, and the Japanese continued to attack westwards. They captured Huangpo on 24 October and were now approaching Hankou.

Dabie Mountains

In the north of the Dabie Mountains, the 3rd Army Group of the 5th Military Region stationed the 19th and 51st Group Armies and the 77th Army in the Liuan and Huoshan regions in Anqing. The 71st Army was tasked with the defense of Fujin Mountain and Gushi County in Henan. The 2nd Group Army was stationed in Shangcheng, Henan and Macheng, Hubei. The 27th Group Army and the 59th Army was stationed in the Yellow River region, and the 17th Army was deployed in theXinyang region to organise the defensive works.

The Japanese attacked in late August with the 2nd Group Army marching from Hefei on two different routes. The 13th Division, on the southern route, breached the Chinese 77th Army's defensive line and captured Huoshan, then turned towards Yejiaji. The nearby 71st Army and the 2nd Group Army made use of their existing positions to resist the Japanese onslaught, halting the Japanese 13th Division. The 16th Division was thus called in to reinforce the attack. On 16 September, the Japanese captured Shangcheng. The defenders retreated southwards out of the city, using their strategic strongholds in the Dabie Mountains to continue the resistance. On 24 October, the Japanese occupied Macheng.

The 10th Division was the main force in the northern route. They breached the Chinese 51st Army's defensive line and captured Liuan on 28 August. On 6 September, they captured Gushi and continued their advance westwards. The Chinese 27th Group Army and the 59th Army gathered in the Yellow River region to resist. After ten days of fierce fighting, the Japanese crossed the Yellow River on 19 September. On the 21st, the Japanese 10th Division defeated the Chinese 17th Group Army and 45th Army, capturing Lushan.

The 10th Division then continued to move westward, but met a Chinese counterattack east of Xinyang and was forced to withdraw back to Lushan. The Japanese 2nd Army Group ordered the 3rd Division to assist the 10th Division in taking Xinyang. On 6 October, the 3rd Division circled back to Xintang and captured the Liulin station of Pinghan Railway. On the 12th, the Japanese 2nd Army captured Xinyang and moved south of the Pinghan Railway to attack Wuhan together with the 11th Army.

Fighting in Guangzhou

Due to the continuing stalemate around Wuhan and the continued influx of foreign aid to Chinese forces from ports in the south, the IJA decided to deploy 3 reserve divisions to pressure the naval shipping lines. It was thus decided to occupy the Guangdong port by way of an amphibious landing. Because of the fighting in Wuhan, the bulk of Chinese forces in Guangzhou had been transferred away. As such, the pace of the occupation was much smoother than expected and the Guangzhou area fell within half a month.

The successive victories attained by the Japanese forces completed the encirclement of Wuhan. Since the loss of the Guangzhou area meant that no more foreign aid would be flowing in, the strategic value of Wuhan was lost. The Chinese Army, hoping to save their remaining forces, thus abandoned the city. The Japanese Army captured Wuchang and Hankou on 26 October and captured Hanyang on the 27th, completing the capture of Wuhan and ending the battle.

Use of chemical weapons

According to Yoshiaki Yoshimi and Seiya Matsuno, Emperor Shōwa authorized, by specific orders (rinsanmei), the use of chemical weapons against the Chinese.[13] During the battle of Wuhan, Prince Kan'in relayed the emperor's orders to use toxic gas 375 times, from August to October 1938.[14] This was despite the express prohibition on the use of chemical weapons in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, the Treaty of Versailles and the Geneva Protocol. A resolution adopted by the League of Nations on 14 May condemned the use of toxic gas by the Imperial Japanese Army.[15]

Aftermath

| Battle of Wuhan | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢會戰 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉会战 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Defense of Wuhan | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢保衛戰 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉保卫战 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 武漢攻略戦 | ||||||

| |||||||

After four months of heavy fighting, the Chinese Air Force suffered extremely heavy losses, its Navy was decimated and the IJA had successfully captured Wuhan. However, the main Chinese land force was still intact and the IJA was heavily weakened. The initial Japanese aim of ending the war in China at Wuhan and destroying the NRA was not met[4], and the battle of Wuhan bought more time for Chinese forces and equipment in Central China to move further inland, laying the foundation for an extended war of resistance. After the capture of Wuhan, the IJA advance in central China was slowed down significantly by multiple battles around Changsha in 1939, 1941, and 1942. No more major offensives were launched until Operation Ichi-Go in 1944, with limited offensives mounted for the sole purpose of training recruits. The Chinese managed to preserve their strength to continue resisting the weakened IJA. At the conclusion of the battle, Japan had only one division remaining in its home islands and was unable to reinforce the 7 divisions of the Kwantung Army in Northeast China and Korea facing 20 Soviet Far East divisions stationed on the border.[16]

Despite the capture of Wuhan, the Japanese suffered over 140,000 casualties. Although Chinese casualties, at 400,000 total, were more than double this number, it was an improvement from the Battle of Shanghai, where Chinese casualties outnumbered Japanese casualties by more than three to one.

See also

References

- ↑ Soviet Fighters in the sky of China

- 1 2 3 Stephen MacKinnon, "The Tragedy of Wuhan, 1938," Modern Asian Studies 30.4 (October 1996): 931–943.

- ↑ CHINA: 1931–1945 ISBN 7-5633-5509-X Page 192

- 1 2 Japanese Imperial Conference, 15 June 1938

- ↑ "Sino-Japanese Air War 1937–45".

- ↑ "Wuhan Diary" 28 February 1938

- ↑ (in Japanese) Tenchosetsu Archived 27 May 2012 at Archive.is — Japanese national holiday (the birthday of the reigning emperor)

- ↑ School of Social Science Georgia Institute of Technology John W. Garver Assistant Professor (1988). Chinese-Soviet Relations, 1937-1945 : The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism: The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism. Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0195363744. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ↑ "Wuhan Daily" 30 April 1938.

- ↑ Hsu Long-hsuen and Chang Ming-kai, History of The Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)

- ↑ "Ten Worst Floods". Archived from the original on 21 June 2006.

- ↑ 伊斯雷爾·愛潑斯坦 (2016). 《人民之戰》. 香港: 和平圖書.

- ↑ Dokugasusen Kankei Shiryō II, Kaisetsu, Jūgonen sensō gokuhi shiryōshū, Funi Shuppankan, 1997, pp.25–29.

- ↑ Yoshimi and Matsuno, ibid. p.28, "Japan's poison gas used against China", The Free Lance-Star, 6 Octobre 1984

- ↑ Bix, Herbert P. (2001). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Perennial. p. 739.

- ↑ Journal of Wuhan University, Volume 60, Issues 1–6, page 364

Further reading

- Stephen R. MacKinnon, includes photographs by Robert Capa, Wuhan, 1938: War, Refugees, and the Making of Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

External links

- (in Chinese) [/big5.huaxia.com/js/zzhg/2005/00362849.html Battle of Wuhan: Shatter the Japanese ambitions!]

- (in Chinese) [/tw.knowledge.yahoo.com/question/%3fqid=1205082319881 Yachoo! Kimo Battle of Wuhan Knowledge]

- (in Chinese) NRA Museum

- Soviet Fighters in the Sky of China IV

- Axis History Forum, Japanese Landing Operations – Yangtze, summer of 1938

Coordinates: 30°34′00″N 114°16′01″E / 30.5667°N 114.2670°E