Battle of Vitoria

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

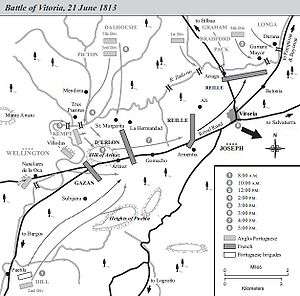

At the Battle of Vitoria (21 June 1813) a British, Portuguese and Spanish army under General the Marquess of Wellington broke the French army under Joseph Bonaparte and Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan near Vitoria in Spain, eventually leading to victory in the Peninsular War.

Background

In July 1812, after the Battle of Salamanca, the French had evacuated Madrid, which Wellington's army entered on 12 August 1812. Deploying three divisions to guard its southern approaches, Wellington marched north with the rest of his army to lay siege to the fortress of Burgos, 140 miles (230 km) away, but he had underestimated the enemy's strength and on 21 October he had to abandon the Siege of Burgos and retreat. By 31 October he had abandoned Madrid too, and retreated first to Salamanca then to Ciudad Rodrigo, near the Portuguese frontier, to avoid encirclement by French armies from the north-east and south-east.

Wellington spent the winter reorganising and strengthening his forces. By contrast, Napoleon withdrew many soldiers to rebuild his main army after his disastrous invasion of Russia. By 20 May 1813 Wellington marched 121,000 troops (53,749 British, 39,608 Spanish and 27,569 Portuguese[3]) from northern Portugal across the mountains of northern Spain and the Esla River to outflank Marshal Jourdan's army of 68,000, strung out between the Douro and the Tagus. The French retreated to Burgos, with Wellington's forces marching hard to cut them off from the road to France. Wellington himself commanded the small central force in a strategic feint, while Sir Thomas Graham conducted the bulk of the army around the French right flank over landscape considered impassable.

Wellington launched his attack with 57,000 British, 16,000 Portuguese and 8,000 Spanish at Vitoria on 21 June, from four directions.[4]

Terrain

The battlefield centres on the Zadorra River, which runs from east to west. As the Zadorra runs west, it loops into a hairpin bend, finally swinging generally to the southwest. On the south of the battlefield are the Heights of La Puebla. To the northwest is the mass of Monte Arrato. Vitoria stands to the east, two miles (3 km) south of the Zadorra. Five roads radiate from Vitoria, north to Bilbao, northeast to Salinas and Bayonne, east to Salvatierra, south to Logroño and west to Burgos on the south side of the Zadorra.

Plans

Jourdan was ill with a fever all day on 20 June. Because of this, few orders were issued and the French forces stood idle. An enormous wagon train of booty clogged the streets of Vitoria. A convoy left during the night, but it had to leave siege artillery behind because there were not enough draft animals to pull the cannons.

Gazan's divisions guarded the narrow western end of the Zadorra valley, deployed south of the river. Maransin's brigade was posted in advance, at the village of Subijana. The divisions were disposed with Leval on the right, Daricau in the centre, Conroux on the left and Villate in reserve. Only a picket guarded the western extremity of the Heights of La Puebla.

Further back, d'Erlon's force stood in a second line, also south of the river. D'Armagnac's division deployed on the right and Cassagne's on the left. D'Erlon failed to destroy three bridges near the river's hairpin bend and posted Avy's weak cavalry division to guard them. Reille's men originally formed a third line, but Sarrut's division was sent north of the river to guard the Bilbao road while Lamartinière's division and the Spanish Royal Guard units held the river bank.

Wellington directed Hill's 20,000-man Right Column to drive the French from the Zadorra defile on the south side of the river. While the French were preoccupied with Hill, Wellington's Right Centre column moved along the north bank of the river and crossed it near the hairpin bend behind the French right flank.

Graham's 20,000-man Left Column was sent around the north side of Monte Arrato. It drove down the Bilbao road, cutting off the bulk of the French army. Dalhousie's Left Centre column cut across Monte Arrato and struck the river east of the hairpin, providing a link between Graham and Wellington.

Battle

Wellingtons plan split his army into four attacking "columns", attacking the French defensive position from south, west and north while the last column cut down across the French rear. Coming up the Burgos road, Hill sent Morillo's Division to the right on a climb up the Heights of La Puebla. Stewart's 2nd Division began deploying to the left in the narrow plain just south of the river. Seeing these moves, Gazan sent Maransin forward to drive Morillo off the heights. Hill moved Col. Henry Cadogan's brigade of the 2nd Division to assist Morillo. Gazan responded by committing Villatte's reserve division to the battle on the heights.

About this time, Gazan first spotted Wellington's column moving north of the Zadorra to turn his right flank. He asked Jourdan, now recovered from his fever, for reinforcements. Having become obsessed with the safety of his left flank, the marshal refused to help Gazan, instead ordering some of D'Erlon's troops to guard the Logroño road.

Wellington thrust James Kempt's brigade of the Light Division across the Zadorra at the hairpin. At the same time, Stewart took Subijana and was counterattacked by two of Gazan's divisions. On the heights, Cadogan was killed, but the Anglo-Spanish force managed to hang on to its foothold. Wellington suspended his attacks to allow Graham's column time to make an impression and a lull descended on the battlefield.

At noon, Graham's column appeared on the Bilbao road. Jourdan immediately realised he was in danger of envelopment and ordered Gazan to pull back toward Vitoria. Graham drove Sarrut's division back across the river, but could not force his way across the Zadorra despite bitter fighting. Further east, Longa's Spanish troops defeated the Spanish Royal Guards and cut the road to Bayonne.

With some help from Kempt's brigade, Picton's 3rd Division from Dalhousie's column crossed to the south side of the river. According to Picton, the enemy responded by pummelling the 3rd with 40 to 50 cannon and a counter-attack on their right flank, still open because they had captured the bridge so quickly, causing the 3rd to lose 1,800 men (over one third of all Allied losses at the battle) as they held their ground.[5] Cole's 4th Division crossed further west. With Gazan on the left and d'Erlon on the right, the French attempted a stand at the village of Arinez. Formed in a menacing line, the 4th, Light, 3rd and 7th Divisions soon captured this position. The French fell back to the Zuazo ridge, covered by their well-handled and numerous field artillery. This position fell to Wellington's attack when Gazan refused to cooperate with his colleague d'Erlon.

French morale collapsed and the soldiers of Gazan and d'Erlon fled from the field. Artillerists left their guns behind as they fled on the trace horses. Soon the road was jammed with a mass of wagons and carriages. The efforts of Reille's two divisions, holding off Graham, allowed tens of thousands of French troops to escape by the Salvatierra road.

Aftermath

The Allied army lost about 5,000 men, with 3,675 British, 921 Portuguese and 562 Spanish casualties.[2] French losses totalled at least 5,200 killed and wounded, plus 2,800 men and 151 cannon captured. By army, the losses were South 4,300, Centre 2,100 and Portugal 1,600. There were no casualty returns from the Royal Guard or the artillery.[6]

French losses were not higher for several reasons. First, the Allied army had already marched 20 miles (32 km) that morning and was in no condition to pursue. Second, Reille's men valiantly held off Graham's column. Third, the valley by which the French retreated was narrow and well-covered by the 3rd Hussar and the 15th Dragoon Regiments acting as rearguard. Last, the French left their booty behind.[2]

Many British soldiers turned aside to plunder the abandoned French wagons, containing "the loot of a kingdom". It is estimated that more than £1 million of booty (perhaps £100 million in modern equivalent) was seized, but the gross abandonment of discipline caused an enraged Wellington to write in a dispatch to Earl Bathurst, "We have in the service the scum of the earth as common soldiers".[7] The British general also vented his fury on a new cavalry regiment, writing, "The 18th Hussars are a disgrace to the name of soldier, in action as well as elsewhere; and I propose to draft their horses from them and send the men to England if I cannot get the better of them in any other manner."[2] (On 8 April 1814, the 18th redeemed their reputation in a gallant charge led by Lieutenant-colonel Sir Henry Murray at Croix d'Orade, shortly before the Battle of Toulouse.)

Order was soon restored, and by December, after detachments had seized San Sebastián and Pamplona, Wellington's army was encamped in France.

The battle was the inspiration for Beethoven's Opus 91, often called the "Battle Symphony" or "Wellington's Victory", which portrays the battle as musical drama. The climax of the movie The Firefly, starring Jeanette MacDonald, occurs with Wellington's attack on the French centre. (The film used music from an opera of the same name by Rudolf Friml, but with a totally different plot.) The battle and French rout also forms the climax to Bernard Cornwell's book Sharpe's Honour.

22 June 2013, Bicentenary of the Battle

British line infantry and highlanders

British line infantry and highlanders Cavalry charge

Cavalry charge Hand-to-hand combat between British and Imperial marksmen

Hand-to-hand combat between British and Imperial marksmen Spanish soldiers

Spanish soldiers French soldiers

French soldiers British column

British column Spanish infantrymen

Spanish infantrymen British highland grenadiers

British highland grenadiers Portuguese infantrymen

Portuguese infantrymen Imperial grenadiers

Imperial grenadiers Anglo-Portuguese advance

Anglo-Portuguese advance Mounted Chasseurs a cheval and horse grenadiers

Mounted Chasseurs a cheval and horse grenadiers

Notes

- ↑ Gates (2002), p. 390.

- 1 2 3 4 Glover (2001), p. 243.

- ↑ Gates (2002), p. 521.

- ↑ Gates (2002), p. 386.

- ↑ Historical Record of the Seventy-fourth Regiment (Highlanders), Richard Cannon, Published by Parker, Furnivall & Parker, 1847

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 427.

- ↑ Wellington to Bathurst, dispatches, p. 496.

References

- Gates, David (2002). The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-9730-6.

- Glover, Michael (2001). The Peninsular War 1807–1814. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-141-39041-7.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, Duke of (1838), The dispatches of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington: during his various campaigns in India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, the Low Countries, and France, from 1799 to 1818, X, John Murray, retrieved 14 November 2007

- Lipscombe, Nick (2010). The Peninsular War Atlas. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84908-364-9.

Further reading

- Fletcher, Ian (2005). Vittoria 1813: Wellington Sweeps the French from Spain. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-98616-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Vitoria. |

Coordinates: 42°51′N 2°41′W / 42.850°N 2.683°W