Battle of Taejon

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Taejon (14–21 July 1950) was an early battle of the Korean War, between American and North Korean forces. Forces of the United States Army attempted to defend the headquarters of the 24th Infantry Division. The 24th Infantry Division was overwhelmed by numerically superior forces of the Korean People's Army (KPA) at the major city and transportation hub of Taejon. The 24th Infantry Division's regiments were already exhausted from the previous two weeks of delaying actions to stem the advance of the KPA.

The entire 24th Division gathered to make a final stand around Taejon, holding a line along the Kum River to the east of the city. Hampered by a lack of communication and equipment, and a shortage of heavy weapons to match the KPA's firepower, the outnumbered, ill-equipped and untrained American forces were pushed back from the riverbank after several days before fighting an intense urban battle to defend the city. After a fierce three-day struggle, the Americans withdrew.

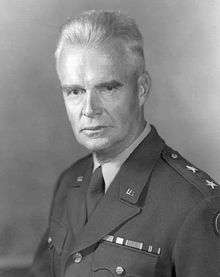

Although they could not hold the city, the 24th Infantry Division achieved a strategic victory by delaying the North Koreans, providing time for other American divisions to establish a defensive perimeter around Pusan further south. The delay imposed at Taejon probably prevented an American rout during the subsequent Battle of Pusan Perimeter. During the action, the KPA captured Major General William F. Dean, the commander of the 24th Infantry Division, and highest ranking American prisoner during the Korean War.

Background

Outbreak of war

Following the invasion of the Republic of Korea (South Korea) by its northern neighbor, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), the United Nations committed forces on behalf of South Korea. The United States subsequently sent ground forces to the Korean peninsula to contain the North Korean invasion and to prevent the collapse of the South Korean state. American forces in the Far East had steadily decreased since the end of World War II, five years earlier. When forces were initially committed, the 24th Infantry Division of the Eighth United States Army, headquartered in Japan, was the closest US division.[3] The division was under-strength, and most of its equipment dated from 1945 and earlier due to defense cutbacks enacted in the first Truman administration. Nevertheless, the division was ordered into South Korea.[4][5]

The 24th Infantry Division was the first US unit sent into Korea to absorb the initial North Korean advances, and disrupt the more numerous North Korean units.[6] The 24th Division effectively delayed the North Korean advance to allow the 7th Infantry Division, 25th Infantry Division, 1st Cavalry Division, and other Eighth Army supporting units to establish a defensive line around Pusan.[6]

Immediately preceding the Battle of Taejon, some of the Bodo League massacres took place around Taejon, where between 3,000 and 7,000 South Korean leftist political prisoners were shot and dumped into mass graves by South Korean troops,[7] partially recorded by a US Army photographer.[8]

Delaying action

Task Force Smith, an advance element of the 24th Infantry Division was badly defeated in the Battle of Osan on 5 July, during the first encounter between American and North Korean forces.[9] Task Force Smith retreated from Osan to Pyongtaek, where US forces were again defeated in the Battle of Pyongtaek.[10] The 24th Infantry Division was repeatedly forced south by the North Korean force's superior numbers and equipment [11]in engagements at Chochiwon, Chonan, Hadong, and Yechon.[10][11] American soldiers were untrained and unprepared at the outbreak of the war, and this lack of training showed in engagements with North Korean units which were much more disciplined. Most of the Americans were out of shape, untrained, undisciplined and had no combat experience.[12] [13]

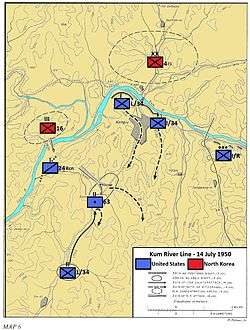

On 12 July, the division's commander, Major General William F. Dean, ordered the division's three regiments, the 19th Infantry Regiment, 21st Infantry Regiment, and the 34th Infantry Regiment, to cross the Kum River, destroying all bridges behind them, and to establish defensive positions around Taejon. Taejon was a major South Korean city 100 miles (160 km) south of Seoul and 130 miles (210 km) northwest of Pusan, and was the site of the 24th Infantry Division's headquarters.[14] Dean formed a line with the 34th Infantry and 19th Infantry facing east, and held the heavily battered 21st Infantry in reserve to the southeast.[15] The Kum River wrapped north and west around the city, providing a defensive line 10 to 15 miles from the outskirts of Taejon, which was surrounded to the south by the Sobaek Mountains. With major railroad junctions and numerous roads leading into the countryside in all directions, Taejon was a major transportation hub between Seoul and Taegu, giving it great strategic value for both the American and North Korean forces.[16] The division was attempting to make a last stand at Taejon, the last place it could conduct a delaying action before the North Korean forces would converge on the unfinished Pusan Perimeter.[17]

Prelude

US 24th Infantry Division

The 24th Infantry Division's three infantry regiments, which had a wartime strength of 3,000 each, were already below strength on their deployment, and heavy losses in the preceding two weeks had reduced their numbers further. The 21st Infantry had 1,100 men left, having suffered 1,433 casualties.[15] The 34th Infantry had only 2,020 men and the 19th had 2,276 men. Another 2,007 men stood in the 24th Infantry Division artillery formations.[18] These counts placed the division's total strength at 11,400.[11] This was severely reduced from the 15,965 men and 4,773 vehicles that had arrived in Korea at the beginning of the month.[3] Each of the regiments had only two battalions of infantry as opposed to the normal three.[11] Large numbers of men had to be pulled from the lines from combat fatigue.[19] Morale was extremely low for the soldiers, who were exhausted from days without sleep.[20] Casualties among the division's commissioned officers were extremely high, forcing younger officers and non-commissioned officers to take leadership positions normally occupied by more experienced ones.[21]

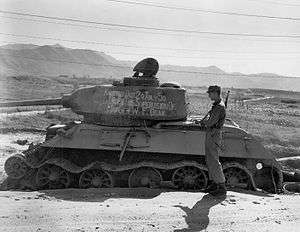

In addition to casualties, shortages of equipment hampered the 24th Infantry Division's efforts. Losses from earlier fighting reduced artillery support to two battalions.[17] Communications equipment, weapons, and ammunition was limited and large amounts of equipment had been lost or destroyed in previous engagements. Most of the radios available to the division did not work, and batteries, communication wire, and telephones to communicate among units were in short supply, with some company formations having only one radio for one squad.[22] The division had no tanks: its new M26 Pershing and older M4A3 Sherman tanks were still en route. One of the few weapons that could penetrate the North Korean T-34 tanks, the 3.5 inch M20 "Super Bazookas" firing M28A2 HEAT rocket ammunition, were in short supply.[23] The paucity of radios and wire hampered communication between and among the American units.[24]

North Korean units

North Korean planners intended for three divisions to attack Taejon from three directions, supported by tanks. The North Korean 3rd Division was ordered to attack from the north, against the flank. The North Korean 4th Division would attack across the Kum River from the east and south, in order to envelop Taejon and the US 24th Infantry Division with it.[25] Eventually they would also be supported by elements of the North Korean 105th Armored Division.[26] Although the North Korean 2nd Infantry Division was ordered to attack from Chongju against the American right flank, it was slow to move and arrived too late to participate in the battle.[27]

The North Koreans advanced on the town with the 3rd and 4th divisions supported by over 50 T-34 tanks. Each North Korean division, normally operating with 11,000 men, was at 60 to 80 percent strength, giving them nearly a two to one numerical superiority over the American forces.[15] The morale of the two divisions was low, owing to repeated air attacks on equipment and overall exhaustion from continuous combat. Political officers promised the divisions they would be able to rest in Taejon after they took the city.[28]

Battle

First North Korean attack

On the morning of 14 July, American soldiers from 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry on the heights 2 miles (3.2 km) above the Kum River spotted T-34s across the river. The T-34s fired on the 3rd Battalion's position from across the river, to no effect.[24] By mid-morning, North Korean infantry were spotted crossing the river by boat and mortar and artillery fire began hitting the 34th Infantry's lines.[29] In the confusion and resulting poor communication, the North Korean infantry managed to move around the American lines.[24] The 1st Battalion, further north, also came under heavy attack by advancing North Korean forces, and though it repulsed the attack with the help of artillery, it was forced to withdraw to safer positions.[30]

In the early afternoon, another attacking force, an estimated 1,000 North Korean troops, crossed the river.[29] The North Koreans captured an outpost of the 63rd Field Artillery Battalion, supporting the 34th Infantry with 105-mm howitzers. They turned a captured machine gun on the battalion's HQ battery and began to fire, taking it by surprise. Artillery fire aimed at the battery destroyed communications and vehicles, and inflicted heavy casualties.[31] Its survivors retreated on foot to the south. Meanwhile, only 250 yards (230 m) away, a battery of the battalion also came under attack by 100 North Korean infantrymen, resulting in similar casualties and retreat. B Battery was attacked by 400 North Koreans, but an advance of South Korean horse cavalry spared the battery from heavy losses, allowing it to make an organized retreat.[32] The 63rd Field Artillery lost all of its guns and 80 of its vehicles, many still intact for North Korean forces to use.[29][33]

Later in the evening, 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry counterattacked the positions but was unable to take them back, in the face of machine gun and small arms fire, and was forced to withdraw by nightfall.[29][34] After this failed attempt to retake the equipment, Dean ordered the positions where the captured equipment was located to be destroyed by an airstrike.[35] With the 1st Battalion having taken heavy casualties and the 3rd Battalion forced to move to counter North Korean attacks, the northwest flank of the American line had been beaten back.[36] The North Korean 4th Division began crossing the river, only slightly impeded by US aircraft attacking its boats.[29][37]

Second North Korean attack

Following the initial penetration, the 34th Infantry line moved south to Nonsan.[38] The 19th Infantry moved its 2nd Battalion to fill some of the gaps left by the 34th,[39] reinforced by Republic of Korea Army troops.[38][39] The combined forces observed a large build-up of North Korean troops on the other side of the river. At 03:00 on 16 July, the North Koreans launched a massive barrage of tank, artillery and mortar fire on the 19th Infantry's positions and North Korean troops began to cross the river in boats.[38] The North Korean forces gathered on the west bank and assaulted the positions of 1st Battalion's C and E companies, followed by a second landing against B Company.[40] North Korean forces pushed against the entire battalion, threatening to overwhelm it. The regimental commander ordered all support troops and officers to the line and they were able to repulse the assault. However, in the melee, North Korean forces infiltrated their rear elements, attacking the reserve forces and blocking supply lines. Stretched thin, the 19th Infantry was unable to hold the line at the Kum River and simultaneously repel the North Korean forces.[41]

That evening, 2nd Battalion was moved to attempt to deal with the North Koreans in the rear but suffered casualties as well, and was unable to break the roadblocks. By 17 July, the 19th Infantry withdrew, and was ordered 25 miles (40 km) southwest to regroup and re-equip. Less than half of 1st Battalion returned, and only two of 2nd Battalion's companies remained intact. All three regiments of the 24th Infantry Division, having each been defeated and overwhelmed, were down to battalion-strength formations.[29][42] The division's 19th and 34th regiments had engaged the North Korean 3rd Infantry Division and the North Korean 4th Infantry Division[43] between 13 and 16 July and suffered 650 casualties among the 3,401 men committed there.[11][29] On 18 July, the Eighth Army commander, Lieutenant General Walton Walker, ordered General Dean to hold Taejon until the 20th so that the 1st Cavalry Division and 25th Infantry Division could establish defensive lines along the Naktong River, forming the Pusan Perimeter.[26][44] As the North Korean push against the US units forced them back, 31 US troops were killed in the Chaplain-Medic Massacre.[45]

Taejon surrounded

The North Koreans then moved against Taejon city.[46] On 19 July, North Korean forces entered Taejon, the site of the 24th Infantry Division's headquarters.[47] The North Korean 3rd Division formed a roadblock between Taejon and Okchon, cutting off the 21st Infantry in its reserve positions. The 21st Infantry was subsequently unable to join the fight.[48] However it attempted to hold the route of escape for the rest of the division during most of the fight at Taejon.[49] At the same time, tanks from the North Korean 105th Armored Division began to enter the city, followed by troops of the 3rd and 4th infantry divisions.[27] There, the North Korean forces deployed, occupying key buildings throughout the city to establish sniper positions. American attacks against these positions later set fire to many of Taejon's wooden buildings.[50] North Korean forces prioritised and attempted to eliminate American gun emplacements, food stores, and ammunition dumps, having received information on the location of these facilities through agents operating in the city.[51]

At Taejon, the battered 24th Infantry Division was ordered to make a stand.[52][53] The 34th Infantry also moved to the city to oppose the North Korean forces, which assaulted it head-on while attempting to flank and cut off retreat from the rear. Dean began ordering elements of the division, including much of his headquarters, to retreat via train to Taegu, although he remained behind.[44] By this time, several M24 Chaffee light tanks had been sent to reinforce the division from A Company of the 78th Tank Battalion.[48][54] Regardless of the additional tanks, on 20 July, North Korean armored units pushed American forces back from Taejon Airfield, several miles northwest of Taejon, overwhelming the last American units defending the Kum River and forcing the remnants of the division into Taejon itself.[55] At this point the city was surrounded and North Korean troops began setting roadblocks along the roads out of the city.[53]

For two days, the 34th Infantry fought the advancing North Koreans in bitter house-to-house fighting. North Korean soldiers continued to infiltrate the city, often disguised as farmers. The remaining elements of the 24th Infantry Division were pushed back block-by-block.[56] Without radios, and unable to communicate with the remaining elements of the division, Dean joined the men on the front lines. At one point, he personally attacked a tank with a hand grenade, destroying it.[57] Large columns of North Korean forces began marching on the city from the south roads, reinforcing those that had crossed the river. American forces pulled back after suffering heavy losses, allowing the North Korean 3rd and 4th divisions to move on the city freely from the north, south, and east roads.[56] The 24th Infantry Division repeatedly attempted to establish its defensive lines, and was repeatedly pushed back by the numerically superior North Koreans.[11][53]

Taejon falls

At the end of the day on 20 July, Dean ordered the headquarters of the 34th Infantry to withdraw. His command was reinforced by several more light tanks from the 1st Cavalry Division. As the tanks fought through a North Korean roadblock, Dean, with a small force of soldiers, followed them.[58] At the edge of the city, the final elements of the 34th Infantry, leaving the city in 50 vehicles, were ambushed and many of their vehicles were destroyed by machine guns and mortars, forcing the Americans to retreat on foot.[59] In the ensuing fight, Dean's jeep made a wrong turn and was separated from the rest of the American forces.[60] Unable to turn back, Dean and his party attempted to retreat to American lines on their own, but 35 days later, alone and lost in the hills, Dean was captured by North Korean forces.[53][61] For most of his incarceration, the North Koreans were not aware of his rank. Dean repeatedly attempted to make the North Koreans kill him for fear of divulging information under torture. North Korean leaders had threatened to harm Dean if he did not cooperate but he was never actually tortured.[62] Eventually his rank was uncovered, but they were unable to gather any intelligence from him.[63]

When the last of the 34th Infantry's defenders left the city, the 21st Infantry, which had been protecting the road to Taegu, also withdrew, leaving Taejon in the hands of the North Korean forces.[64]

Aftermath

By the end of the battle, the Americans counted 922 men killed and 228 wounded with almost 2,400 missing, most of these men from the 34th Infantry.[65] Evidence suggests that the North Koreans executed some of the missing and captured prisoners immediately after the battle.[66] Although badly mauled, the 24th Infantry Division accomplished its mission of delaying North Korean forces from advancing until 20 July.[67][68][69] By that time, American forces had set up the Pusan Perimeter to the southeast. On 22 July, the 24th Infantry Division was relieved by the 1st Cavalry Division. It was put under the command of Major General John H. Church, in the absence of Dean, whose whereabouts were unknown. After three weeks of fighting, the division had suffered almost 30 percent casualties.[70] Historians attribute the substantial tactical losses of the 24th Infantry division to a lack of training, equipment, and readiness, owing to extended time spent on occupation duty in Japan and without training.[71]

North Korean casualties could not be estimated because of lack of communications between units during the battle, which limited the value of American signals intelligence.[4][64] North Korean armor suffered heavy losses. A total of 15–20 North Korean tanks were destroyed by anti-tank weapons and US aircraft, and North Korean prisoners estimated that 15 76-mm guns, six 122-mm mortars, and 200 artillerymen were lost. Losses among North Korean infantry were heavy, especially in the NK 3rd Division.[72] The NK 3rd division was reported between 60 and 80 percent of its strength at the beginning of the battle and was reduced to 50 percent by its end, with total casualties ranging from 1,250 to 3,300.[73]

By the time the battle ended, the United States had moved enough forces onto the Korean Peninsula to roughly equal the number of attacking North Korean forces.[67] For its delaying actions in and around Taejon, the 24th Infantry Division was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation and the Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation.[27] The division went into reserve status while it rested and rebuilt, and the first unit of the division back into action, the 19th Infantry Regiment, moved to the front lines of the Pusan Perimeter on 1 August.[11]

The first two Medals of Honor for the Korean War were awarded for the Battle of Taejon.[74] For his actions on the front lines, Dean was awarded the first Medal of Honor, although he remained a prisoner of the North Koreans until the end of the war (released in September 1953).[63] A second soldier, Sergeant George D. Libby, received the Medal of Honor posthumously, for tending to wounded soldiers during the evacuation: he repeatedly passed over shelled roads to help evacuate them. He was killed while trying to evacuate more soldiers.[68] Additionally, a chaplain, Herman G. Felhoelter, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for an incident later known as the Chaplain-Medic Massacre which took place during the battle near the Kum River.[45]

References

Citations

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 134.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 350.

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 59.

- 1 2 Varhola 2000, p. 3.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 60.

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 52.

- ↑ Hanley & Jae-soon 2008.

- ↑ Hanley & Hyung-jin 2010.

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 15.

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Varhola 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 60.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 63.

- ↑ Summers 2001, p. 266.

- 1 2 3 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 88.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 121.

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 92.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 122.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 125.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 147.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 123.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 89.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 96.

- 1 2 Millett 2010, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 Summers 2001, p. 269.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Millett 2010, p. 191.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 97.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 127.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 128.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 90.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 129.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 91.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 98.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 135.

- 1 2 Millett 2010, p. 187.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 93.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 94.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 96.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 79.

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 97.

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 143.

- ↑ Millett 2010, p. 192.

- ↑ Malkasian 2001, p. 23.

- 1 2 Summers 2001, p. 268.

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 20.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 99.

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 21.

- ↑ Malkasian 2001, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 Millett 2010, p. 193.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 103.

- ↑ Summers 2001, p. 267.

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 102.

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 7

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 99.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 104.

- ↑ Varhola 2000, p. 84.

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ Inc, Time (September 14, 1953), "Heroism of General Dean is revealed when a North Korean relates details", Life Magazine Vol. 35 No. 11, ISSN 0024-3019

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 100.

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 107.

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 22.

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 103.

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ Millett 2010, p. 190.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 101.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 180.

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 179.

- ↑ Millett 2010, p. 194.

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 8.

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War we Lost, Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0781810197

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War, Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004), Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-1980-7

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001), This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History – Fiftieth Anniversary Edition, Potomac Books, ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3

- Malkasian, Carter (2001), The Korean War, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-282-1

- Millett, Allan R. (2010), The War for Korea, 1950–1951: They Came from the North, University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8

- Summers, Harry G. (2001), Korean War Almanac, Replica Books, ISBN 978-0-7351-0209-5

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4

Online sources

- Hanley, Charles J.; Jae-soon, Chang (6 December 2008), Children 'executed' in 1950 South Korean killings, Associated Press

- Hanley, Charles J.; Hyung-jin, Kim (10 July 2010), Korea bloodbath probe ends; US escapes much blame, Google, Associated Press, retrieved 2 August 2010