Battle of Tabu-dong

| Battle of Tabu-dong | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter | |||||||

US 1st Cavalry Division troops look down on Hill 518 from an observation post north of Waegwan, September 1950. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 14,703 | 7,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

600 killed 2,000 wounded | 5,000 killed, captured and deserted | ||||||

The Battle of Tabu-dong was an engagement between United Nations (UN) and North Korean (NK) forces early in the Korean War from September 1 to September 18, 1950, in the vicinity of Tabu-dong, north of Taegu in South Korea. It was a part of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter, and was one of several large engagements fought simultaneously. The battle ended in a victory for the United Nations after large numbers of United States (US) and Republic of Korea (ROK) troops repelled a strong North Korean attack.

Holding positions north of the crucial city of Taegu, the US Army's 1st Cavalry Division stood at the center of the Pusan Perimeter defensive line, tasked with keeping the United Nations Command headquarters secured from attacks from the North Korean People's Army. On September 1, the NK 3rd Division attacked as part of the Great Naktong Offensive.

What followed was a two-week battle around Tabu-dong and Waegwan in which the North Koreans were able to gradually push the 1st Cavalry Division back from its lines. However, the North Koreans were not able to force the US troops to withdraw completely or push the UN out of Taegu. When the UN counterattacked at Inchon, the North Koreans were forced to abandon their attack on Tabu-dong.

Background

Pusan Perimeter

From the outbreak of the Korean War and the invasion of South Korea by the North, the North Korean People's Army had enjoyed superiority in both manpower and equipment over both the Republic of Korea Army and the United Nations forces dispatched to South Korea to prevent it from collapsing.[1] The North Korean strategy was to aggressively pursue UN and ROK forces on all avenues of approach south and to engage them aggressively, attacking from the front and initiating a double envelopment of both flanks of the unit, which allowed the North Koreans to surround and cut off the opposing force, which would then be forced to retreat in disarray, often leaving behind much of its equipment.[2] From their initial June 25 offensive to fights in July and early August, the North Koreans used this strategy to effectively defeat any UN force and push it south.[3] However, when the UN forces, under the Eighth United States Army, established the Pusan Perimeter in August, the UN troops held a continuous line along the peninsula which North Korean troops could not flank, and their advantages in numbers decreased daily as the superior UN logistical system brought in more troops and supplies to the UN army.[4]

When the North Koreans approached the Pusan Perimeter on August 5, they attempted the same frontal assault technique on the four main avenues of approach into the perimeter. Throughout August, the NK 6th Division, and later the NK 7th Division engaged the US 25th Infantry Division at the Battle of Masan, initially repelling a UN counteroffensive before countering with battles at Komam-ni[5] and Battle Mountain.[6] These attacks stalled as UN forces, well equipped and with plenty of reserves, repeatedly repelled North Korean attacks.[7] North of Masan, the NK 4th Division and the US 24th Infantry Division sparred in the Naktong Bulge area. In the First Battle of Naktong Bulge, the North Korean division was unable to hold its bridgehead across the river as large numbers of US reserve forces were brought in to repel it, and on August 19, the NK 4th Division was forced back across the river with 50 percent casualties.[8][9] In the Taegu region, five North Korean divisions were repulsed by three UN divisions in several attempts to attack the city during the Battle of Taegu.[10][11] Particularly heavy fighting took place at the Battle of the Bowling Alley where the NK 13th Division was almost completely destroyed in the attack.[12] On the east coast, three more North Korean divisions were repulsed by the South Koreans at P'ohang-dong during the Battle of P'ohang-dong.[13] All along the front, the North Korean troops were reeling from these defeats, the first time in the war their strategies were not working.[14]

September push

In planning its new offensive, the North Korean command decided any attempt to flank the UN force was impossible due to the support of the UN navy.[12] Instead, they opted to use frontal attack to breach the perimeter and collapse it as the only hope of achieving success in the battle.[4] Fed by intelligence from the Soviet Union the North Koreans were aware the UN forces were building up along the Pusan Perimeter and that it must conduct an offensive soon or it could not win the battle.[15] A secondary objective was to surround Taegu and destroy the UN and ROK units in that city. As part of this mission, the North Korean units would first cut the supply lines to Taegu.[16][17]

On August 20, the North Korean commands distributed operations orders to their subordinate units.[15] The North Koreans called for a simultaneous five-prong attack against the UN lines. These attacks would overwhelm the UN defenders and allow the North Koreans to break through the lines in at least one place to force the UN forces back. Five battle groupings were ordered.[18] The center attack called for the NK 3rd Division, NK 13th Division, and NK 1st Division break through the US 1st Cavalry Division and ROK 1st Division to Taegu.[19]

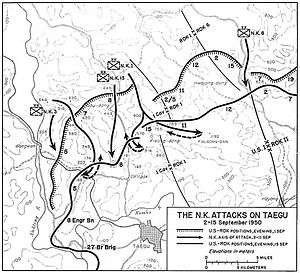

Battle

While four divisions of the NK II Corps attacked south in the P'ohang-dong, Kyongju, and Yongch'on area, the remaining three divisions of the corps-the 3rd, 13th, and 1st conducted their converging attack on Taegu from the north and northwest.[20] The NK 3rd Division was to attack in the Waegwan area northwest of Taegu, the NK 13th Division down the mountain ridges north of Taegu along and west of the Sangju-Taegu road, and the NK 1st Division along the high mountain ridges just east of the road.[21]

Defending Taegu, the US 1st Cavalry Division had a front of about 35 miles (56 km). Division Commander Major General Hobart R. Gay outposted the main avenues of entry into his zone and kept his three regiments concentrated behind the outposts.[20] At the southwestern end of his line Gay initially controlled the US 3rd Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, which had been attached to the 1st Cavalry Division. On September 5 the British 27th Commonwealth Brigade, in its first commitment in the Korean War, replaced that battalion. Next in line northward, the US 5th Cavalry Regiment defended the sector along the Naktong around Waegwan and the main Seoul highway southeast from there to Taegu. Eastward, the US 7th Cavalry Regiment was responsible for the mountainous area between that highway and the hills bordering the Sangju road. The US 8th Cavalry Regiment, responsible for the latter road, was astride it and on the bordering hills.[21]

Hill 518

Eighth United States Army commander Lieutenant General Walton Walker ordered the 1st Cavalry Division to attack north on September 1 in an effort to divert some of the North Korean strength from the US 2nd and 25th Infantry Divisions in the south.[22] Gay's initial decision upon receipt of this order was to attack north up the Sangju road, but his staff and regimental commanders all joined in urging that the attack instead be against Hill 518 in the US 7th Cavalry zone. Only two days before, Hill 518 had been in the ROK 1st Division zone and had been considered a North Korean assembly point. The US 1st Cavalry Division, accordingly, prepared for an attack in the 7th Cavalry sector and for diversionary attacks by two companies of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, on the 7th Cavalry's right flank. This left the 8th Cavalry only one infantry company in reserve. The regiment's 1st Battalion was on the hill mass to the west of the Bowling Alley and north of Tabu-dong; its 2nd Battalion was astride the road.[21]

This planned attack against Hill 518 coincided with the defection of NK Major Kim Song Jun of the NK 19th Regiment, NK 13th Division. He reported that a full-scale North Korean attack was to begin at dusk that day. The NK 13th Division, he said, had just taken in 4,000 replacements, 2,000 of them without weapons, and was now back to a strength of approximately 9,000 men. Upon receiving this intelligence, Gay alerted all front-line units to be prepared for the attack.[21]

Complying with Eighth Army's order for a spoiling attack against the North Koreans northwest of Taegu, Gay ordered the 7th Cavalry to attack on September 2 and seize Hill 518. Hill 518, also called Suam-san, is a large mountain mass 5 miles (8.0 km) northeast of Waegwan and 2 miles (3.2 km) east of the Naktong River. It curves westward from its peak to its westernmost height, Hill 346, from which the ground drops abruptly to the Naktong River.[23] Situated north of the lateral Waegwan-Tabu–dong road, and about midway between the two towns, it was a critical terrain feature dominating the road between the two places. After securing Hill 518, the 7th Cavalry attack was to continue on to Hill 314. Air strikes and artillery preparations were to precede the infantry attack.[24]

On the morning of September 2 the US Air Force delivered a 37-minute strike against Hills 518 and 346. The artillery then laid down its concentrations on the hills, and after that the planes came over again with napalm, leaving the heights on fire. Just after 10:00, and immediately after the final napalm strike, the 1st Battalion, US 7th Cavalry, attacked up Hill 518.[24] The heavy air strikes and the artillery preparations had failed to dislodge the North Koreans.[25] From their positions they delivered mortar and machine gun fire on the climbing infantry, stopping the weak, advanced US force short of the crest. In the afternoon the US battalion withdrew from Hill 518 and attacked northeast against Hill 490, from which other North Korean troops had fired in support of the North Koreans on Hill 518.[26]

The next day at 12:00, the newly arrived 3rd Battalion resumed the attack against Hill 518 from the south, as did the 1st Battalion the day before, in a column of companies that resolved itself in the end into a column of squads. Again the attack failed. Other attacks failed on September 4. A North Korean forward observer captured on Hill 518 said that 1,200 North Koreans were dug in on the hill and that they had large numbers of mortars and ammunition to hold out.[26]

North Korean flanking moves

While these attacks were in progress on its right, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment, on September 4 attacked and captured Hill 303. The next day it had difficulty in holding the hill against counterattacks.[26] By September 4 it had become clear that the NK 3rd Division in front of the 5th and 7th Cavalry Regiments was also attacking, and despite continued air strikes, artillery preparations, and infantry efforts on Hill 518, it was infiltrating large numbers of its troops to the rear of the attacking United States forces.[22] That night large North Korean forces came through the gap between the 3rd Battalion on the southern slope of Hill 518 and the 2nd Battalion westward. The North Koreans turned west and occupied Hill 464 in force. By September 5, Hill 464 to the rear of the US 7th Cavalry had more North Koreans on it than Hill 518 to its front.[26] North Koreans cut the Waegwan to Tabu-dong road east of the regiment so that its communications with other US units now were only to the west.[25] During the day the 7th Cavalry made a limited withdrawal on Hill 518, giving up on capturing the hill.[26]

On the division right, Tabu-dong was in North Korean hands, on the left Waegwan was a no-man's land, and in the center strong North Korean forces were infiltrating southward from Hill 518.[27] The 7th Cavalry Regiment in the center could no longer use the Waegwan-Tabu-dong lateral supply road behind it, and was in danger of being surrounded.[28] After discussing a withdrawal plan with Walker, Gay on September 5 issued an order for a general withdrawal of the 1st Cavalry Division during the night to shorten the lines and to occupy a better defensive position.[22] The movement was to progress from right to left beginning with the 8th Cavalry Regiment, then the 7th Cavalry in the Hill 518 area, and finally the 5th Cavalry in the Waegwan area. This withdrawal caused the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, to give up a hill it had just attacked and captured near the Tabu-dong road on the approaches of the Walled City of Ka-san. In the 7th Cavalry sector the 1st, 3rd, and 2nd Battalions were to withdraw in that order, after the withdrawal of the 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry, on their right. The 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, on Hill 303 north of Waegwan was to cover the withdrawal of the 7th Cavalry and hold open the escape road.[28]

Further US withdrawal

In his withdrawal instructions for the 7th Cavalry, Colonel Cecil Nist, the regimental commander, ordered the 2nd Battalion to disengage from the North Koreans to its front and attack to its rear to gain possession of Hills 464 and 380 on the new main line of resistance to be occupied by the regiment.[27] Efforts to gain possession of Hill 464 by other elements had failed in the past several days.[29]

Heavy rains fell during the night of September 5-6 and mud slowed all wheeled and tracked vehicles in the withdrawal. The 1st Battalion completed its withdrawal without opposition. During its night march west, the 3rd Battalion column was joined several times by groups of North Korean soldiers who apparently thought it was one of their own columns moving south. They were made prisoners and taken along in the withdrawal. Nearing Waegwan at dawn, the battalion column was taken under North Korean mortar and T-34 tank fire after daybreak and sustained 18 casualties.[29]

The 2nd Battalion disengaged from the North Korean and began its withdrawal at 03:00, September 6. The battalion abandoned two of its own tanks, one because of mechanical failure and the other because it was stuck in the mud. The battalion moved to the rear in two main groups: G Company to attack Hill 464 and the rest of the battalion to seize Hill 380, farther south. The North Koreans quickly discovered that the 2nd Battalion was withdrawing and attacked it. The battalion commander, Major Omar T. Hitchner, and his operations officer, Captain James T. Milam, were killed. In the vicinity of Hills 464 and 380 the battalion discovered at daybreak that it was virtually surrounded by North Koreans. Nist thought that the entire battalion was lost.[30]

Moving by itself and completely cut off from all other units, G Company, numbering only about 80 men, was hardest hit. At 08:00, nearing the top of Hill 464, it surprised and killed three North Korean soldiers. Soon after, North Korean automatic weapons and small arms fire struck the company. All day G Company maneuvered around the hill but never gained its crest. At mid-afternoon it received radio orders to withdraw that night. The company left six dead on the hill and, carrying its wounded on improvised litters of ponchos and tree branches, it started down the shale slopes of the mountain in rain and darkness. Halfway down, friendly fire injured Captain Herman L. West, the G Company commander. The company scattered but West reassembled it. Cautioning his men to move quietly and not to fire their weapons, West led his men to the eastern base of Hill 464 where he went into a defensive position for the rest of the night.[30]

South flank

On the division left, meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry, on Hill 303 came under heavy attack and the battalion commander wanted to withdraw. The regimental commander, told him he could not do so until the 7th Cavalry had cleared on its withdrawal road. This battalion suffered heavy casualties before it abandoned Hill 303 on the September 6 to the North Koreans.[30]

While G Company was trying to escape from Hill 464, the rest of the 2nd Battalion was cut off at the eastern base of Hill 380, to the south. Nist organized all the South Korean carriers he could find before dark and loaded them with water, food, and ammunition for the 2nd Battalion, but the carrier party was unable to find the battalion. At dawn on September 7 the men in G Company was discovered and attacked by North Korean troops in nearby positions. At this time, West heard what he recognized as fire from American weapons on a knob to his west. There, G Company was reunited with its Weapons Platoon which had become separated from him during the night.[30]

The Weapons Platoon, after becoming separated from the rest of the company, encountered North Koreans on the trail it was following three times in the night, but in each instance neither side fired, each going on its way. At dawn, the platoon ambushed a group of North Koreans, killing 13 and capturing three North Koreans. From the body of a North Korean officer the men took a briefcase containing important documents and maps. These showed that Hill 464 was an assembly point for part of the NK 3rd Division in its advance from Hill 518 toward Taegu.[31]

Later in the day on September 7, Captain Melbourne C. Chandler, acting commander of the 2nd Battalion, received word of G Company's location on Hill 464 from an aerial observer and sent a patrol which guided the company safely to the battalion at the eastern base of Hill 380. The battalion, meanwhile, had received radio orders to withdraw by any route as soon as possible. It moved southwest into the 5th Cavalry sector.[31]

North Korean advance

East of the 2nd Battalion, the North Koreans attacked the 1st Battalion in its new position on September 7 and overran the battalion aid station, killing four and wounding seven men. That night the 1st Battalion on division orders was attached to the 5th Cavalry Regiment. The rest of the 7th Cavalry Regiment moved to a point near Taegu in division reserve. During the night of September 7-8 the 5th Cavalry Regiment on division orders withdrew still farther below Waegwan to new defensive positions astride the main Seoul-Taegu highway.[31] The North Korean 3rd Division was still moving reinforcements across the Naktong.[27] Observers sighted barges loaded with troops and artillery pieces crossing the river 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Waegwan on the evening of the 7th. On the 8th the North Korean communiqué claimed the capture of Waegwan.[31]

The next day the situation grew worse for the 1st Cavalry Division. On its left flank, the NK 3rd Division forced the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, to withdraw from Hill 345, 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Waegwan. The North Korean pressed forward and the 5th Cavalry was immediately locked in hard, seesaw fighting on Hills 203 and 174. The 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, before it left that sector to rejoin its regiment, finally captured the latter hill after four attacks.[31]

Only with difficulty did the 5th Cavalry Regiment hold Hill 203 on September 12. Between midnight and 04:00 on September 13, the North Koreans attacked again and took Hill 203 from E Company, Hill 174 from L Company, and Hill 188 from B and F Companies. In an afternoon counterattack the regiment regained Hill 188 on the south side of the highway, but failed against Hills 203 and 174 on the north side. On the 14th, I Company again attacked Hill 174, which had by now changed hands seven times.[31] In this action the company suffered 82 casualties. Even so, the company held only one side of the hill, the North Korean held the other, and grenade battles between the two continued for another week.[32] The battalions of the 5th Cavalry Regiment were so low in strength at this time that they were not considered combat effective.[33] This seesaw battle continued in full 8 miles (13 km) northwest of Taegu.[34][35]

North Korean withdrawal

The UN counterattack at Inchon collapsed the North Korean line and cut off all their main supply and reinforcement routes.[36] On September 19 the UN discovered the North Koreans had abandoned much of the Pusan Perimeter during the night, and the UN units began advancing out of their defensive positions and occupying them.[37] Most of the North Korean units began conducting delaying actions attempting to get as much of their army as possible into North Korea.[38] The North Koreans withdrew from the Masan area first, the night of September 18–19. After the forces there, the remainder of the North Korean armies withdrew rapidly to the North.[38] The US units rapidly pursued them north, passing over the Naktong River positions, which were no longer of strategic importance.[39]

Aftermath

The North Korean 3rd Division was almost completely destroyed in the battles. The division had numbered 7,000 men at the beginning of the offensive on September 1.[18] Only 1,000 to 1,800 men from the division were able to retreat back into North Korea by October. The majority of the division's troops had been killed, captured or deserted.[40] All of NK II Corps was in a similar state, and the North Korean army, exhausted at Pusan Perimeter and cut off after Inchon, was on the brink of defeat.[41]

By this time, the US 1st Cavalry Division suffered 770 killed, 2,613 wounded, 62 captured during its time at Pusan Perimeter.[42] This included about 600 casualties, with around 200 killed in action it had already suffered during the Battle of Taegu the previous month. American forces were continually repulsed but able to prevent the North Koreans from breaking the Pusan Perimeter.[43] The division had numbered 14,703 on September 1, but was in excellent position to attack despite its casualties.[44]

Sgt. John Raymond Rice, a Ho Chunk Indian awarded the Bronze Star in World War II, was killed at Tabu-dong on Sept. 6, 1950 leading a squad of Company A, 8th Cavalry Regiment. When his remains were returned for burial in Sioux City, Iowa the public cemetery denied him a burial because of his race. President Truman personally intervened, and arranged for his burial with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. A subsequent U.S. Supreme Court case determined in 1954 that racial segregation at public cemeteries was legal.[45][46][47]

References

Citations

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 392

- ↑ Varhola 2004, p. 6

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 138

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 393

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 367

- ↑ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 149

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 369

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 130

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 139

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 353

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 143

- 1 2 Catchpole 2001, p. 31

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 136

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 135

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 139

- ↑ Millett 2000, p. 508

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 181

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 395

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 396

- 1 2 Millett 2000, p. 507

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1998, p. 411

- 1 2 3 Catchpole 2001, p. 34

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 412

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 413

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 182

- 1 2 3 4 5 Appleman 1998, p. 414

- 1 2 3 Catchpole 2001, p. 35

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 415

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 418

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1998, p. 419

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 420

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 186

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 421

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 36

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 187

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 568

- ↑ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 179

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 570

- ↑ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 180

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 603

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 604

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 16

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 14

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 382

- ↑ Huston, Luther (May 10, 1955). "BURIAL BIAS PLEA REJECTED AGAIN". New York Times.

- ↑ "Truman Sets Arlington Interment For Indian Denied 'White' Burial". New York Times. August 30, 1951.

- ↑ "INDIAN HERO'S BURIAL SET FOR WEDNESDAY". New York Times. August 31, 1951.

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War We Lost, Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War, Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0

- Bowers, William T.; Hammong, William M.; MacGarrigle, George L. (2005), Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea, Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 978-1-4102-2467-5

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004), Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-1980-7

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001), This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History – Fiftieth Anniversary Edition, Potomac Books Inc., ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3

- Gugeler, Russell A. (2005), Combat Actions in Korea, University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 978-1-4102-2451-4

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4