Battle of Perast

| Battle of Perast | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Cretan War (1645–69) | |||||||

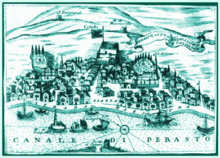

Venetian engraving of Perast | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Krsto Vicković | Mehmed-aga Rizvanagić † | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| more than 5,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

Location within Montenegro | |||||||

The Battle of Perast (Serbian: Перашка битка) was a battle for control over Venetian held Perast (modern day Montenegro) fought in 1654 between defending forces of Venetian Republic from Perast accompanied by hajduks[1] and attacking forces of Ottoman Empire from Sanjak of Herzegovina. Commander of defending Perast forces was Krsto Vicković while Ottoman forces were led by Mehmed-aga Rizvanagić.

Venetian forces from Perast were victorious and successfully repelled Ottoman attack in the battle which is in some sources referred to as most glorious victory in their history.[2]

Background

In 1654, Ottoman forces controlled almost whole north-western part of the Kotor Bay, so they perceived Perast as some kind of thorn in their side.[3] On the other hand, Perast had important strategic importance for the Venetian Republic because it protected important Venetian-held city of Kotor.[4]

Battle of Perast followed an unsuccessful attempt of Venetian forces to capture Knin in early 1654. Victorious Ottoman forces of Sanjak of Herzegovina were ordered to attack Perast per request of Ottomans expelled from Risan in 1648-49 by Perast forces. Additional motif was successful attack of Perast forces on Popovo in 1654.[1]

The Ottomans were embittered because of the constant attacks of hajduks from Perast.[5] Around 1,500 refugees fled eastern Herzegovina in early 1654 and settled Venetian-held territories in Kotor Bay, near Perast. There were at least 500 hajduks among them.[6] Although they were of Orthodox faith, hajduks were treated well by Venetian authorities in Perast who granted them some land,[7] creating some kind of Military Frontier between Venetian and Ottoman territories in Kotor Bay.[8] Since 1654 Perast became known as hajduks' nest.[9]

Forces

The Ottoman forces that attacked Perast were from Sanjak of Herzegovina governed by Čengić, a secret Venetian agent.[10] Čengić was afraid that his betrayal would be discovered if he refuse to attack Perast, so he reluctantly decided to organize an attack.[10] The Ottoman forces were under direct command of expelled dizdar of Risan, Mehmed-aga Rizvanagić.[1] According to Vuk Karadžić, it was said that Rizvanagić was originally from Kovačević family of Grahovo (near Nikšić, modern-day Montenegro).[11] The Ottoman infantry from Sanjak of Hercegovina was supported by fustas from Ottoman-held Ulcinj and Herceg Novi.[8]

Venetian forces of 43 men[12] from Perast were under command of Krsto Vickov Visković.[2] Substantial number of hajduks, who migrated from eastern Herzegovina[13] to Perast in the first half of May 1654, participated in defence of Perast.[14][8]

About 30 Venetian warships from Perast were unable to participate in defence of Perast because they were far away, on the open sea, together with their crews.[1] The small fortress above the town (The Fortress of the Holy Cross) together with the chain of towers spread across the town had an important role in the defence of Perast, completely surrounded by Ottoman territories.

Battle

Perast authorities were informed about the planned Ottoman attack by Orthodox priest Radul of Riđani.[1] Before the battle the civilian population took shelters.[14]

According to some sources, the attack was intentionally poorly organized by Čengić and as consequence it lasted only for three hours.[10] Other sources emphasize that the attack was well organized and supported by simultaneous attack of fustas of Ottoman navy and Ulcinj pirates who attacked other Venetian held towns in Kotor Bay.[8]

Defenders brought the icon of Madonna and Child from Our Lady of the Rocks islet off the coast of Perast and placed it to the walls of their town. According to the legend Madonna threw ashes into the eyes of attackers and defended the town.[15]

Perast forces prepared their tactic in advance. During the battle they saved their ammunition and together with hajduks organized brave charges into Ottoman forces, causing their panic.[1]

During the Battle of Perast Ottoman forces burned nearby Banja Monastery.[16] The sources differ regarding the Ottoman casualties. According to some sources Ottoman commander Rizvanbegović and 62 Ottoman soldiers were killed during this battle, while most of 200 wounded Ottomans soon died.[17] Some sources present figure of more than 70 killed and 300 wounded Ottomans.[1] Many sources emphasize role of hajduks in this battle.[18] According to some of them, hajduks ambushed Ottoman forces, killed 80 and wounded 800 Ottomans and captured Rizvanagić.[14] Most sources agree that Rizvanagić was killed during this battle, probably during Ottoman attack on one of town's towers (the tower of Mara Krilova).[19] According to epic poetry, Rizvanbegović was killed from rifle by his blood brother Tripo Burović.[8] During this battle mother of Perast captain Vicko Mažarević was kidnapped by the Ottomans and taken to Trebinje where she soon died.[20]

Aftermath

Eight days after the battle Petar Zrinski, thrilled with the victory, visited Perast for three days and presented a sword of Vukša Stepanović to the town. The sword had inscriptions on Cyrillic and Latin scripts, with the presentation of double-headed eagle and short text.[21] This sword is still preserved in Perast.

On 9 June 1654, Perast sent a delegation to Venice with the request to be abolished from paying taxes on their vine for next ten years. Venetian senate accepted their request.[17]

Andrija Zmajević wrote a poem Boj peraški (Battle of Perast) dedicated to celebrating this event. Another poem (Spjevanje događaja boja peraškoga) about this battle was written by Perast Catholic friar Ivan Krušala.[22]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kalezić 1970, p. 24.

- ↑ JAZU 1954, p. 197.

- ↑ Adriatic Sea 1962, p. 1806.

- ↑ Nezirović 2004, p. 257.

- ↑ Stanojević 1956, p. 8.

- ↑ Sbutega 2006, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 4 5 СКЗ 1993, p. 379.

- ↑ Svjetlost 1959, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Stanojević & Vasić 1975, p. 134.

- ↑ Aleksić 1958, p. 690.

- ↑ Popović 1896, p. 75.

- ↑ Samardžić 1990, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Jačov 1990, p. 41.

- ↑ Београдски универзитет 1967, p. 83.

- ↑ Đurović 1969, p. 26.

- 1 2 NK 1986, p. 65.

- ↑ JLZ 1980, p. 49.

- ↑ muzej 1969, p. 129.

- ↑ Adriatic Sea 1962, p. 1869.

- ↑ OMHD 2007, p. 354.

- ↑ Pavić 1970, p. 180.

Sources

- Kalezić, Danilo (1970). Kotor. Grafički zavod Hrvatske.

- Đurović, Ratko (1969). Crnom Gorom. "Binoza," Grafički zavod Hrvatske.

- NK (1986). Zbornik izveštaja o istraživanjima Boke Kotorske. Naučna knjiga.

- Adriatic Sea (1962). Pomorski zbornik.

- Naval art and science (2005). Godišnjak Pomorskog Muzeja u Kotoru. Naval art and science.

- Stanojević, Gligor; Vasić, Milan (1975). Istorija Crne Gore (3): od početka XVI do kraja XVIII vijeka. Titograd: Redakcija za istoriju Crne Gore. OCLC 799489791.

- Pavić, Milorad (1970). Istorija srpske knjiz̆evnosti baroknog doba: (XVII i XVIII vek). Nolit.

- JAZU (1954). Zbornik Historijskog instituta Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti. Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti.

- OMHD (2007). Dubrovnik. Ogranak Matice Hrvatske Dubrovnik.

- СКЗ (1993). Istorija srpskog naroda: knj. Od najstarijih vremena do Maričke bitke (1371). Srpska književna zadruga.

- Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović; Aleksić, R. (1958). Pjesme junačke srednijijeh vremena. Prosveta.

- Београдски универзитет (1967). Анали филолошког факултета. Београдски универзитет.

- muzej, Kotor (Montenegro) Pomorski (1969). Godišnjak Pomorskog Muzeja u Kotoru.

- Popović, Dr. Đorđe (1896). Istorija Crne Gore. Djurčić.

- Jačov, Marko (1990). Srbi u mletačko-turskim ratovima u XVII veku. Sveti arhijerejski sinod Srpske pravoslavne crkve.

- Sbutega, Antun (2006). Storia del Montenegro: dalle origini ai giorni nostri. Rubbettino. ISBN 978-88-498-1489-7.

- JLZ (1980). Enciklopedija Jugoslavije: Bje-Crn. Jugoslavenski Leksikografski Zavod.

- Samardžić, Radovan (1990). Seobe srpskog naroda od XIV do XX veka: zbornik radova posvećen tristagodišnjici velike seobe Srba. Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva.

- Svjetlost (1959). Iz naše narodne epike: dio Hajdučke borbe oko Dubrovnika i naša narodna pjesma. (Prilog proučavanju postanka i razvoja naše narodne epike). Svjetlost.

- Nezirović, Muhamed (2004). Krajišnička pisma. Preporod.

- Stanojević, Gligor (1956). Bajo Pivljanin. Prosveta.

Further reading

- Serović, P. D., O starinskom maču, koji se čuva u Perastu, u Boki Kotorskoj, Narodna starina, Zagreb