Battle of Hattin

| Battle of Hattin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Wars of the Crusader States | |||||||

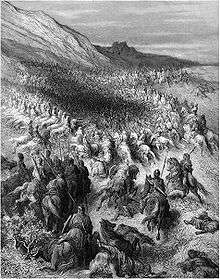

The Battle of Hattin, from a 15th-century manuscript | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| All (fighters) | believed light | ||||||

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Salah ad-Din, known in the West as Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, from a nearby extinct volcano.

The Muslim armies under Saladin captured or killed the vast majority of the Crusader forces, removing their capability to wage war.[9] As a direct result of the battle, Muslims once again became the eminent military power in the Holy Land, re-conquering Jerusalem and several other Crusader-held cities.[9] These Christian defeats prompted the Third Crusade, which began two years after the Battle of Hattin.

Location

The battle took place near Tiberias in present-day Israel. The battlefield, near the town of Hittin, had as its chief geographic feature a double hill (the "Horns of Hattin") beside a pass through the northern mountains between Tiberias and the road from Acre to the east. The Darb al-Hawarnah road, built by the Romans, served as the main east-west passage between the Jordan fords, the Sea of Galilee and the Mediterranean coast.

Background

Guy of Lusignan became king of Jerusalem in 1186, in right of his wife Sibylla, after the death of Sibylla's son Baldwin V. The Kingdom of Jerusalem was at this time divided between the "court faction" of Guy, Sibylla, and relative newcomers to the kingdom such as Raynald of Châtillon, Gerard of Ridefort and the Knights Templar; and the "nobles’ faction", led by Raymond III of Tripoli, who had been regent for the child-king Baldwin V and had opposed the succession of Guy. Raymond III of Tripoli had supported the claim of Isabella of Jerusalem and her husband Humphrey IV of Toron, and he led the rival faction to the court party. Open warfare was only prevented when Humphrey of Toron swore allegiance to Guy, ending the succession dispute. The Muslim chronicler Ali ibn al-Athir claimed that Raymond was in a "state of open rebellion" against Guy.[10]

In the background of these divisions Saladin had become vizier of Egypt in 1169, and had taken Damascus in 1174 and Aleppo in 1183. He controlled the entire Southern and Eastern flanks of the Crusader states. Through the use of propaganda he united his subjects under Sunni Islam, and convinced them that he would wage Holy War to push the Christian Franks from Jerusalem. However, Saladin often made strategic truces with the Franks when there was a need to deal with political problems in the Muslim World, and one such truce was made in 1185. It was rumoured amongst the Franks that Raymond III of Tripoli had made a deal with Saladin under which Saladin would make him King of Jerusalem in return for peace. This rumour was echoed by Ibn al Athir, but it is unclear whether it was true. Raymond III was certainly reluctant to engage in battle with Saladin.

In 1187 Reynald of Châtillon raided a Muslim caravan when the truce with Saladin was still in place, and some accounts claim that Saladin's sister was raped during the attack. Saladin swore that he would kill Reynald, and sent his son Al-Afdal ibn Salah ad-Din and the emir Gökböri to raid Frankish lands surrounding Acre. Gerard de Ridefort and the Templars engaged Gökböri in the Battle of Cresson in May, where they were heavily defeated.[11] The Templars lost around 150 knights and 300 footsoldiers, who had made up a great part of the military of Jerusalem. Phillips states that "the damage to Frankish morale and the scale of the losses should not be underestimated in contributing towards the defeat at Hattin".[12]

In July Saladin laid siege to Tiberias, where Raymond III's wife Eschiva was trapped. In spite of this Raymond argued that Guy should not engage Saladin in battle, and that Saladin could not hold Tiberias because his troops would not stand to be away from their families for so long. The Knights Hospitaller also advised Guy not to provoke Saladin. However, Gerard de Ridefort advised Guy to advance against Saladin, and Guy took his advice. Norman Housley suggests that this was because "the minds of both men had been so poisoned by the political conflict 1180-87 that they could only see Raymond's advice as designed to bring them personal ruin", and also because he had spent Henry II of England's donations in calling the army, and was reluctant to disband it without a battle.[13] This was a gamble on Guy's part, as he left only a few knights to defend the city of Jerusalem.

Siege of Tiberias

In late May Saladin assembled the largest army he had ever commanded, around 30,000 men including about 12,000 regular cavalry. He inspected his forces at Tell-Ashtara before crossing the River Jordan on June 30. The opposing Crusader army amassed at La Saphorie; it consisted of around 20,000 men, including 1,200 knights from Jerusalem and Tripoli and 50 from Antioch. Though the army was smaller than Saladin's it was still larger than those usually mustered by the Crusaders.[4] After reconciling, Raymond and Guy met at Acre with the bulk of the crusader army. According to the claims of some European sources, aside from the knights there was a greater number of lighter cavalry, and perhaps 10,000 foot soldiers, supplemented by crossbowmen from the Italian merchant fleet, and a large number of mercenaries (including Turcopoles) hired with money donated to the kingdom by Henry II, King of England.[14] Also the army's standard was the relic of the True Cross,[4] carried by the Bishop of Acre, who was there in place of the ailing Patriarch Heraclius.

On July 2, Saladin, who wanted to lure Guy into moving his field army away from their encampment by the springs at La Saphorie, personally led a siege of Raymond's fortress of Tiberias while the main Muslim army remained at Kafr Sabt. The garrison at Tiberias tried to pay Saladin off, but he refused, later stating that "when the people realized they had an opponent who could not be tricked and would not be contented with tribute, they were afraid lest war might eat them up and they asked for quarter...but the servant gave the sword dominion over them." The fortress fell the same day. A tower was mined and, when it fell, Saladin's troops stormed the breach killing the opposing forces and taking prisoners.

Holding out, Raymond's wife Eschiva was besieged in the citadel. As the mining was begun on that structure, news was received by Saladin that Guy was moving the Frank army east. The Crusaders had taken the bait.

Guy's decision to leave the secure base provided by his well-watered assembly point at La Saphorie, was the result of a Crusader war council held the night of July 2. Though reports of what happened at this meeting are biased due to personal feuds among the Franks, it seems Raymond argued that a march from Acre to Tiberias was exactly what Saladin wanted while La Saphorie was a strong position for the Crusaders to defend. Furthermore, Guy shouldn't worry about Tiberias, which Raymond held personally and was willing to give up for the safety of the kingdom. In response to this argument, and despite their reconciliation (internal court politics remaining strong), Raymond was accused of cowardice by Gerard and Raynald. The latter influenced Guy to attack immediately.

Guy thus ordered the army to march against Saladin at Tiberias, which is indeed just what Saladin had planned, for he had calculated that he could defeat the crusaders only in a field battle rather than by besieging their fortifications.

Saladin had also unexpectedly gained the alliance of the Druze community based in Sarahmul led by Jamal ad-Din Hajji, whose father Karama was an age-old ally of Nur ad-Din Zangi.[15] The city of Sarahmul had been sacked by the crusaders on various occasions and according to Jamal ad-Din Hajji the crusaders even manipulated the Assassins to kill his three elder brothers.

The battle

On July 3 the Frankish army started out towards Tiberias, harassed constantly by Muslim archers. They passed the Springs of Turan, which were entirely insufficient to provide the army with water. At midday Raymond of Tripoli decided that the army would not reach Tiberias by nightfall, and he and Guy agreed to change the course of the march and here to the left in the direction of the Springs of Kafr Hattin, only 6 miles (9.7 km away). From there they could march down to Tiberias the following day. The Muslims however positioned themselves between the Frankish army and the water so that the Franks were forced to pitch camp overnight on the arid plateau near the village of Meskenah. The Muslims surrounded the camp so closely that "a cat could not have escaped". According to Ibn al Athir the Franks were "despondent, tormented by thirst" whilst Saladin's men were jubilant in anticipation of their victory.[16]

Throughout the night the Muslims further demoralized the crusaders by praying, singing, beating drums, showing symbols, and chanting. They set fire to the dry grass, making the crusaders' throats even drier.[17] The Crusaders were now thirsty, demoralized and exhausted. The Muslim army by contrast had a caravan of camels bring goatskins of water up from Lake Tiberias (now known as the Sea of Galilee).[18]

On the morning of July 4, the crusaders were blinded by smoke from the fires set by Saladin's forces. The Ayyubid army was arrayed in three divisions: the centre under Saladin, the right under his nephew Al-Muzaffar Umar (Taki ad-Din) and the left, commanded by Gökböri.[19] The Franks came under fire from Muslim mounted archers from the division commanded by Gökböri, who had been resupplied with 400 loads of arrows that had been brought up during the night. Gerard and Raynald advised Guy to form battle lines and attack, which was done by Guy's brother Amalric. Raymond led the first division with Raymond of Antioch, the son of Bohemund III of Antioch, while Balian and Joscelin III of Edessa formed the rearguard.

Thirsty and demoralized, the crusaders broke camp and changed direction for the springs of Hattin, but their ragged approach was attacked by Saladin's army which blocked the route forward and any possible retreat. Count Raymond launched two charges in an attempt to break through to the water supply at the Lake Tiberias. The second of these enabled him to reach the lake and make his way to Tyre.[20]

After Raymond escaped, Guy's position was now even more desperate. Most of the Christian infantry had effectively deserted by fleeing in a mass onto the Horns of Hattin where they played no further part in the battle. Overwhelmed by thirst and wounds, many were killed on the spot without resistance while the remainder were taken prisoner. Their plight was such that five of Raymond's knights went over to the Muslim leaders to beg that they be mercifully put to death.[17] Guy attempted to pitch the tents again to block the Muslim cavalry. The Christian knights and mounted serjeants were disorganized, but still fought on.

Now the crusaders were surrounded and, despite three desperate charges on Saladin's position, were broken up and defeated. An eyewitness account of this is given by Saladin's 17-year-old son, al-Afdal. It is quoted by Muslim chronicler Ibn al-Athir:[21]

When the king of the Franks [Guy] was on the hill with that band, they made a formidable charge against the Muslims facing them, so that they drove them back to my father [Saladin]. I looked towards him and he was overcome by grief and his complexion pale. He took hold of his beard and advanced, crying out "Give the lie to the Devil!" The Muslims rallied, returned to the fight and climbed the hill. When I saw that the Franks withdrew, pursued by the Muslims, I shouted for joy, "We have beaten them!" But the Franks rallied and charged again like the first time and drove the Muslims back to my father. He acted as he had done on the first occasion and the Muslims turned upon the Franks and drove them back to the hill. I again shouted, "We have beaten them!" but my father rounded on me and said, "Be quiet! We have not beaten them until that tent [Guy's] falls." As he was speaking to me, the tent fell. The sultan dismounted, prostrated himself in thanks to God Almighty and wept for joy.

Surrender of crusaders

Prisoners after the battle included Guy, his brother Amalric II, Raynald de Chatillon, William V of Montferrat, Gerard de Ridefort, Humphrey IV of Toron, Hugh of Jabala, Plivain of Botron, Hugh of Gibelet, and other barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Perhaps only as few as 3,000 Christians escaped the defeat.

Guy of Lusignan and Reynald of Chatillon were brought to Saladin's tent. Saladin offered Guy a drink, which was a sign in Muslim culture that the prisoner would be spared, although Guy was unaware of this. Guy passed the goblet to Reynald, but Saladin struck it from his hands, saying "I did not ask this evil man to drink, and he would not save his life by doing so". He then charged Reynald with breaking the truce. Some reports, such as that of Baha al' Din, claim that Saladin then executed Reynald himself with a single stroke of his sword. However, others record that Saladin struck Reynald as a sign to his bodyguards to behead him. Guy assumed that he would also be beheaded, but Saladin assured him that "kings do not kill kings."[22][23]

Saladin commanded that the other captive barons were to be spared and treated humanely. All 200[24] of the Templar and Hospitaller Knights taken prisoner were executed on Saladin's orders, with the exception of the Grand Master of the Temple.[25][26] The executions were by decapitation. Saint Nicasius, a Knight Hospitaller venerated as a Christian martyr, is said to have been one of the victims.[27]

Imad ed-Din, Saladin's secretary, wrote:

"Saladin ordered that they should be beheaded, choosing to have them dead rather than in prison. With him was a whole band of scholars and sufis and a certain number of devout men and ascetics, each begged to be allowed to kill one of them, and drew his sword and rolled back his sleeve. Saladin, his face joyful, was sitting on his dais, the unbelievers showed black despair."[28]

Captured turcopoles (locally recruited mounted archers employed by the crusader states) were also executed on Saladin's orders. While nominally Christian, these auxiliaries were regarded as renegades who had betrayed Islam.[29]

The rest of the captured knights and soldiers were sold into slavery, and one was reportedly bought in Damascus in exchange for some sandals.[30] The high ranking Frankish barons captured were held for ransom.

Aftermath

The True Cross was supposedly fixed upside down on a lance and sent to Damascus. Some of Saladin's men now left the army, taking lower ranking Frankish prisoners with them as slaves.[31] On Sunday, July 5, Saladin traveled the six miles (10 km) to Tiberias and, there, Countess Eschiva surrendered the citadel of the fortress. She was allowed to leave for Tripoli with all her family, followers, and possessions.[32] Raymond of Tripoli, having escaped the battle, died of pleurisy later in 1187.[33] Guy was taken to Damascus as a prisoner and the other noble captives were eventually ransomed.[34]

In fielding an army of 20,000 men, the Crusaders states had reduced the garrisons of their castles and fortified settlements. The heavy defeat at Hattin meant there was little reserve with which to defend against Saladin's forces.[35] The importance of the defeat is demonstrated by the fact that in its aftermath fifty-two[36] towns and fortifications were captured by Saladin's forces.[37] By mid-September, Saladin had taken Acre, Nablus, Jaffa, Toron, Sidon, Beirut, and Ascalon. Tyre was saved by the arrival of Conrad of Montferrat, resulting in Saladin's assault being repulsed with heavy losses. Jerusalem was defended by Queen Sibylla, Patriarch Heraclius, and Balian, who subsequently negotiated its surrender to Saladin on October 2 (see Siege of Jerusalem).

According to the chronicler Ernoul, news of the defeat caused Pope Urban III to die of shock.

When Joscius, Archbishop of Tyre told Pope Gregory VIII of the disastrous defeat at Hattin, he issued the bull Audita tremendi calling for a new crusade. In England and France the Saladin tithe was enacted to raise funds for the new crusade.

The subsequent Third Crusade did not get underway until 1189. The three separate contingents of the Third Crusade were led by Philip II of France, Richard I of England, and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor.

In popular culture

- Kingdom of Heaven (film), movie

Panorama

For succession of related campaigns, see also

For a succession of related campaigns leading up to the Battle of Hattin on July 3–4, 1187, see:

- 1179: Battle of Montgisard

- 1179: Battle of Marj Ayyun

- 1179: Battle of Jacob's Ford

- 1182: Battle of Belvoir Castle

- 1183: Battle of Al-Fule

- 1187: Battle of Cresson

References

- Notes

- ↑ Nicolle, David (2011-12-20), Saladin, ISBN 9781780962368

- ↑ Nicolle, David (2011-12-20), Saladin, ISBN 9781780962368

- ↑ Konstam 2004, p. 133

- 1 2 3 4 Riley-Smith 2005, p. 110

- ↑ Nicolle, David (1993), Hattin 1187: Saladin's Greatest Victory. Campaign Series #19, Osprey Publishing, p. 59

- ↑ Nicolle, David (1993), Hattin 1187: Saladin's Greatest Victory. Campaign Series #19, Osprey Publishing, p. 61

- ↑ Madden 2005

- ↑ Konstam 2004, p. 119

- 1 2 Madden 2000

- ↑ Arab Historians of the Crusades, Francesco Gabrieli, Account of Ibn al'Athir of the Events leading up to Hattin

- ↑ Nicholson and Nicolle, p. 55

- ↑ The Crusades 1095-1197, Jonathan Phillips, 2002

- ↑ http://www.historytoday.com/norman-housley/saladins-triumph-battle-hattin-1187

- ↑ O'Shea 2006, p. 190

- ↑ Nicolle, David (2011-12-20), Saladin, ISBN 9781780962368

- ↑ Norman Housley, History Today Article, The Battle of Hattin

- 1 2 Steven Runciman. page 458, "A History of the Crusades. The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East", Cambridge University Press 1968, SBN 521 06162 8

- ↑ Nicolle, David (1993), Hattin 1187: Saladin's Greatest Victory. Campaign Series #19, Osprey Publishing, p. 64

- ↑ Runciman. p. 455

- ↑ Richard, Jean. The Crusades c1071-c1291. p. 207. ISBN 0-521-625661

- ↑ D. S. Richards, trans., The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athīr for the Crusading Period from al-Kāmil fi'l-ta'rīkh by ʻIzz al-Dīn Ibn al-Athīr, Part 2: The Years 541-589/1146-1193: The Age of Nur al-Din and Saladin (Ashgate, 2007) pg. 323.

- ↑ The Crescent and the Cross Documentary, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TchhrTzaP5A

- ↑ Saladin in his Time, P H Newby

- ↑ Payne, Robert. The Crusades. p. 208. ISBN 1-85326-689-2.

- ↑ Runciman, Stephen (1968), A History of the Crusades: Vol. 2 The Kingdom of Jerusalem, Cambridge University Press, p. 460

- ↑ Nicholson, Helen. The Knights Templar. p. 54. ISBN 0-7509-3839-0.

- ↑ http://www.netgalaxy.it/san-nicasio.htm

- ↑ Gabrieli, Francesco (1989), Arab Historians of the Crusades, Dorset Press, p. 138

- ↑ Richard, Jean. The Crusades c1071-c1291. p. 207. ISBN 0-521-625661.

- ↑ Newby

- ↑ Steven Runciman. page 460, "A History of the Crusades. The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East", Cambridge University Press 1968, SBN 521 06162 8

- ↑ Steven Runciman. page 461, "A History of the Crusades. The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East", Cambridge University Press 1968, SBN 521 06162 8

- ↑ Steven Runciman. page 469, "A History of the Crusades. The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East", Cambridge University Press 1968, SBN 521 06162 8

- ↑ Steven Runciman. page 462, "A History of the Crusades. The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East", Cambridge University Press 1968, SBN 521 06162 8

- ↑ Smail 1995, p. 33

- ↑ Mayer, Hans Eberhard. The Crusades. p. 135. ISBN 0-19-873097-7.

- ↑ Gibb 1969, p. 585

- Bibliography

- Gibb, Sir Hamilton A. R. (1969) [1955], "The Rise of Saladin, 1169–1189", A History of the Crusades: The First Hundred Years (2nd ed.), London: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 563–589

- Konstam, Angus (2004), Historical Atlas of the Crusades, London: Mercury Books, ISBN 978-1-904668-00-8

- Madden, Thomas (2000), A Concise History of the Crusades, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-8476-9430-3

- Madden, Thomas (2005), Crusades: The Illustrated History, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-03127-6

- Nicholson, H and Nicolle, D (2006) God's Warriors: Knights Templar, Saracens and the Battle for Jerusalem, Osprey Publishing.

- O'Shea, Stephen (2006), Sea of Faith: Islam and Christianity in the Medieval Mediterranean World, Profile Books, ISBN 978-1-86197-521-8

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005), The Crusades: A History, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8264-7269-4

- Runciman, Steven (1952), A History of the Crusades, vol. II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100–1187, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Smail, R. C. (1995) [1956], Crusading Warfare, 1097–1193 (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-45838-2

Further reading

- Baldwin, M. W. (1936), Raymond III of Tripolis and the Fall of Jerusalem (1140–1187), Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Brundage, James A. (1962), "De Expugnatione Terrae Sanctae per Saladinum", The Crusades: A Documentary Survey, Milwaukee: Marquette University Press

- Delcourt, Thierry ed. (2009), Sébastien Mamerot, Les Passages d'Outremer. A chronicle of the Crusades, Cologne: Taschen, p. 145, ISBN 978-3-8365-0555-0

- Edbury, Peter W. (1996), The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, Aldershot: Ashgate, ISBN 1-84014-676-1

- Gabrieli, Francesco (1989), Arab Historians of the Crusades, New York: Dorset Press, ISBN 0-88029-460-4

- Gillingham, John (1999), Richard I, Yale English Monarchs, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-07912-5

- Holt, P. M. (1986), The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517, New York: Longman, ISBN 0-582-49302-1

- Lyons, M. C.; Jackson, D. E. P. (1982), Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22358-X

- Nicholson, R. L. (1973), Joscelyn III and the Fall of the Crusader States, 1134–1199, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-03676-8

- Nicolle, David (1993), Hattin 1187: Saladin's Greatest Victory. Osprey Campaign Series #19, Osprey Publishing, p. 96, ISBN 1-85532-284-6

- Nicolle, David (2005), Hattin 1187: Saladin's Greatest Victory, Praeger Illustrated Military History Series, Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, ISBN 0-275-98840-6

- Nicolle, David (2011), Saladin: Leadership-Strategy-Conflict, Command #12, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84908-317-1

- Phillips, Jonathan (2002), The Crusades 1095–1187, New York: Longman, ISBN 0-582-32822-5

- Reston, Jr., James (2001), Warriors of God: Richard the Lionheart and Saladin in the Third Crusade, New York: Anchor Books, ISBN 0-385-49562-5

- Setton, Kenneth, ed. (1958), A History of the Crusades, vol. I, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Hattin. |