Battle of Grahamstown

| Battle of Grahamstown | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Fifth Xhosa War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Xhosa people | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Willshire | Makana | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Approx. 350 British Army troops plus 130 KhoiKhoi | 6,000+ | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 British killed | c.1000 Xhosa killed | ||||||

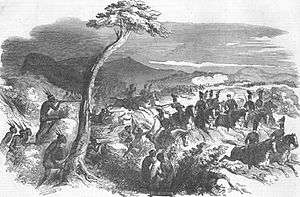

The Battle of Grahamstown took place on 22 April 1819, during the 5th Xhosa War, at the frontier settlement of Grahamstown in what is now the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The confrontation involved the defence of the town by the British garrison, aided by a group of Khoikhoi marksmen, from an attack by a large force of attacking Xhosa warriors.[1]

Prelude

Following problems with cattle rustling in the area, the British commander Sommerset ordered Xhosa chief Ngqika to speak to other Xhosa chiefs and put an end to the cattle and horse theft. But Ngqika had no real power over the other chiefs. Sommerset offered military support to the Xhosa chief Ngqika in his efforts to curb the cattle theft. When Ngqika was attacked and defeated at Amalinde by rival chief Ndlambe in 1818, the British gave instruction to Lieutenant Colonel Brereton to proceed to Ngqika's assistance with a combined force of burghers and soldiers. In December 1818, Colonel Brereton crossed the Fish River, and after joining forces with Ngqika's adherents, attacked Ndlambe. Instead of retalitating, Ndlambe's warriors retreated into dense bush, which afforded them shelter. Their kraals were destroyed, and 23 000 head of cattle were seized. The British commander withdrew his army before Ndlambe was thoroughly defeated, and on reaching Grahamstown the burghers were disbanded and permitted to return to their homes. [2]

By 1819, the frontier settlement of Grahamstown had been in existence for seven years. It consisted of about 30 buildings, including a military barracks. Apart from a few hundred civilians, there were about 350 soldiers from various regiments stationed in Grahamstown under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Willshire. Ndlambe was then convinced by the prophet-warrior Makana, also known as Nxele or Links (left-handed), that the Gods would be on his side if the British at Grahamstown were attacked and that the British bullets would turn to water. He therefore gave Makana his backing for an attack and sent a message to Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Willshire, the British commander at Grahamstown, notifying him of his intentions. Makana had sent a notice of war to Willshire the day before, saying he would ‘breakfast’ with him on the 22nd, to which Willshire responded by saying ‘Everything will be ready for you on your arrival,’ [3]

Xhosa attack

On 22 April 1819 Makana (with the backing of Ndlambe) attacked Grahamstown in broad daylight with a force of at least 6000 warriors predominantly armed only with spears. The Xhosa attacked in three divisions. The left division under Makana attacked the barracks on the edge of town whilst the other two divisions, under the command of Mdushane (son of Ndlambe) and Kobe, attacked the town itself.[4]

The defenders, consisting of 48 men of the 38th (1st Staffordshire) Regiment of Foot, 39 men of the Colonial Troop, 135 of the Royal African Corps, 82 Khoikhoi of the Cape Regiment and local citizens, held off the attackers with musket and artillery fire.[5] They were reinforced during the battle by the arrival of a group of some 130 Khoikhoi natives under the command of Jan Boezak.[6]

The main battle lasted about an hour. The Xhosa lost at least a 1000 men for the loss of only three British soldiers and retreated to the Kei River.[7]

One of the legendary stories of the conflict was that of soldier's wife Elizabeth Salt who walked through the Xhosa ranks unharmed to smuggle in a keg of much-needed gunpowder. It is believed that she disguised ammunition as a child she was carrying, and the Xhosa warriors did not want to attack a woman and a child. [8]

Aftermath

After the battle, Willshire hunted Makana down and four months later he surrendered. He was sent into imprisonment on Robben Island from where he escaped with others in a boat on Christmas Day, 1819, only to drown in the process when the boat capsized.[9]

Makana had such an impact that his followers who were waiting for his return created a saying " Ukuza kukaNxele" which means waiting for the impossible in isiXhosa. A public lecture called Ukuza kukaNxele /The Return of Makhanda was held by Makana's descendants celebrating his role in the struggle for land. [10]

The municipality under which Grahamstown falls is now known as Makana Local Municipality

As a result of the battle the territory between the Great Fish River and the Keiskamma River was added to the colony and Willshire built upon it. Within a year of the battle, 500 1820 Settlers had arrived from Britain in an attempt by the Cape government to boost the local English-speaking population and thus help to permanently defend the Cape's eastern frontier against the Xhosa, leading to the establishment of the white enclave of Albany.

The site of the battle which is located on a hill close to what is now known as Fort England Hospital has come to be called "Egazini" ("Place of Blood"). The area has also grown into a low-income township.The Egazini Memorial, erected to honour the fallen Xhosa warriors, was unveiled by the Department of Arts & Culture in 2001, and consists of a raised toposcope on the far corner of the original battle site. The battlefield site is used as an informal playing field, and the toposcope is now in a state of poor repair.[11]

A newer part of the Memorial was added in 2015, and is within a fenced off area to the West of the battlefield. This area houses a number of mosaic pillars by local artists, each commemorating some aspect of the history of Egazini/Battle of Grahamstown and the surrounding areas (many depict amaXhosa proverbs). There's also a mosaic toposcope pointing towards some of the key places in early Grahamstown/iRhini's history. Most of the artwork was developed by the Egazini Outreach Project.[12]

Elizabeth Salt is immortalised on a monument at the 1820 Settlers Monument in Grahamstown.[13]

Fort Willshire was erected on the Keiskamma River by the British military during the Fifth Frontier War (1818–1819) and named after Colonel T Willshire. During the 1830s it served as a marketplace for trade. It was also Sir Benjamin D’Urban’s base of operations during the Sixth Frontier War (1834–1835). [14]

References

- ↑ "The fifth Frontier War: Sangoma Makana attacks Grahamstown under the patronage of Xhosa Chief Ndlambe, and is defeated". South African History Online. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ "The fifth Frontier War: Sangoma Makana attacks Grahamstown under the patronage of Xhosa Chief Ndlambe, and is defeated". South African History Online. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "The Battle of Grahamstown". South African Tourism. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ "The fifth Frontier War: Sangoma Makana attacks Grahamstown under the patronage of Xhosa Chief Ndlambe, and is defeated". South African History Online. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ Couzens, Tim. Battles of South Africa. p. 71 Battle of Grahamstown.

- ↑ "The fifth Frontier War: Sangoma Makana attacks Grahamstown under the patronage of Xhosa Chief Ndlambe, and is defeated". South African History Online. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "The fifth Frontier War: Sangoma Makana attacks Grahamstown under the patronage of Xhosa Chief Ndlambe, and is defeated". South African History Online. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "The Battle of Grahamstown". South African Tourism. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ "The fifth Frontier War: Sangoma Makana attacks Grahamstown under the patronage of Xhosa Chief Ndlambe, and is defeated". South African History Online. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "The Impossible happened - Makhanda 'Returned'". Albany Museum. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "The Impossible happened - Makhanda 'Returned'". Albany Museum. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "Place of Blood". Geocaching. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "Place of Blood". Geocaching. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "PThe ruins of the historic Prinsloo farmstead.David Krut" (PDF). David Krut. Retrieved 25 June 2017.