Battle of Flores (1591)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Flores was a naval engagement of the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585 fought off the Island of Flores between an English fleet of 22 ships under Lord Thomas Howard[2] and a Spanish fleet of 55 ships under Alonso de Bazán.[1] Sent to the Azores to capture the annual Spanish treasure convoy, when a stronger Spanish fleet appeared off Flores, Howard ordered his ships to flee to the north,[5] saving all of them except the galleon Revenge commanded by Admiral Sir Richard Grenville.

After transferring his ill crew men onshore back to his ship, he led the Revenge in a rear guard action against 55 Spanish ships. Allowing the British fleet to retire to safety. The crew of the Revenge sank and damaged several Spanish ships during a day and night running battle. The Revenge was boarded many times by different Spanish ships and repelled each attack successfully. When Admiral Sir Richard Grenville was badly wounded, his surviving crew surrendered. Lord Alfred Tennyson wrote a poem about the battle entitled The Revenge: a Ballad of the Fleet.

Background

In order to impede a Spanish naval recovery after the Armada, Sir John Hawkins proposed a blockade of the supply of treasure being acquired from the Spanish Empire in the Americas by a constant naval patrol designed to intercept Spanish ships. Revenge was on such a patrol in the summer of 1591 under the command of Sir Richard Grenville. The Spanish, meanwhile, had dispatched a fleet of some 55 ships under Alonso de Bazán, having under his orders Generals Martín de Bertendona and Marcos de Aramburu.[6] Bazán learned that the English were patrolling around the northern Azores. In late August 1591, having been joined by 8 Portuguese flyboats under Luis Coutinho,[2] the Spanish fleet came upon the English. Howard's fleet was caught while undergoing repairs and when the crews, many of whom were suffering an epidemic of fever, were resting ashore.

Battle

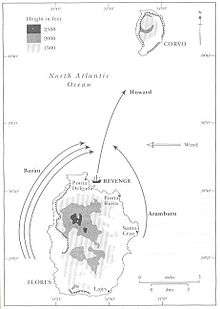

Bazán tried to surprise the English fleet at anchor, but Sancho Pardo's Vice-flagship lost their bowsprit, forcing the attack to be delayed.[2] It was not until 5 PM when Bazán's ships bore down the channel which separated Flores and Corvo islands.[2] Howard, alerted to the arrival of the Spanish, managed to slip away to sea.[3] An exchange of fire took place between both fleets before they became separated.[2] Grenville, however, preferred to fight and went straight through the Spaniards, who were approaching from the eastward.[5]

Meanwhile, Defiance, Howard's flagship, received heavy gunfire from Aramburu's San Cristóbal before withdrawing from the battle. Revenge was left behind and directly engaged by Claudio de Viamonte's San Felipe. Viamonte boarded the English galleon, suffering the misfortune of the grappling hook parting after having only passed 10 men aboard her.[2] Shortly after Martín de Bertendona's San Bernabé did the same, this time successfully, and managed to rescue seven survivors of San Felipe´s boarding party. San Bernabé´s grappling was decisive to the fate of Revenge, because the English warship lost the advantage of her long-range naval guns. Conversely, the heavy musketry fire of the Spanish infantry forced the English gunners to abandon their post in order to repulse the attack.[7]

At dusk, having dispersed the bulk of the English fleet, San Cristobal rammed Revenge underneath its aft-castle, putting on board of the English ship a second boarding party which captured her colours. The Spanish soldiers got as far forward as far as the mainmast before being forced to retreat due to the heavy musketry fire made from the aftcastle.[2] San Cristóbal's bow had been shattered by the ramming and she had to ask for reinforcements.[2] Antonio Manrique's Asunción and Luis Coutinho's flyboat La Serena attacked then at the same time, increasing the number of ships beating the Revenge to five, which was still grappled by the galleons San Bernabé and the damaged San Cristóbal.[2] Grenville held them back with cannon and musket fire until, being himself badly injured and Revenge severely damaged, completely dis-masted and with 150 men killed or unable to fight, surrendered.[4] During the night Manrique's and Coutinho's ships sank after they collided with each other.[5]

Aftermath

Despite the damage Grenville had inflicted, the Spanish treated Revenge's survivors honourably.[8] Grenville, who had been taken aboard Bazán's flagship, died two days later.[4] The Spanish Treasure Fleet rendezvoused with Bazán soon after, and the combined fleet sailed to Spain.[5] They were overtaken by a week-long storm during which Revenge and 15 Spanish warships and merchant vessels were lost.[5] Revenge sank with her mixed prize-crew of 70 Spaniards and English prisoners near the island of Terceira, at the approximate position 38°46′9″N 27°22′42″W / 38.76917°N 27.37833°W.[9]

The battle, however, marked the resurgence of Spanish naval power[7] and proved that the English chances of catching and defeating a well-defended treasure fleet were remote.[8] It also hinted at what might have happened in Gravelines in 1588 if Medina Sidonia had succeeded in luring the English ships within grappling range of the Armada, and if the cannonballs had actually fit the Spanish cannon (they'd been manufactured in different areas of the Spanish Habsburg Empire and so were not all designed in the same way, shape or size).[7]

See also

References

Bibliography

- Earle, Pearl (2004). The last fight of the Revenge. Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77484-8.

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1898). Armada Española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y Aragón (in Spanish). III. Madrid, Spain: Est. tipográfico "Sucesores de Rivadeneyra".

- Hammer, Paul E. J. (2003). Elizabeth's wars: war, government, and society in Tudor England, 1544–1604. Hampshire, USA: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-91942-2.

- Konstam, Anguas; MacBride, Angus (2000). Armada Elizabethan Sea Dogs 1560–1605. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-015-5.

- Paine, Lincoln P. (2003). Elizabeth's Warships of the world to 1900. New York, USA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-98414-7.

- Simpson, Wallis (2001). The reign of Elizabeth. Oxford, UK: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-32735-4.