Battle of Fish Creek

| Battle of Fish Creek | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the North-West Rebellion | |||||||

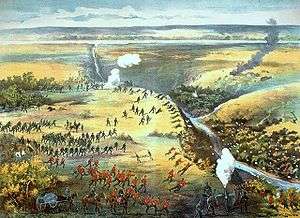

Contemporary lithograph of the Battle of Fish Creek. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Provisional Government of Saskatchewan (Métis) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Gabriel Dumont | Frederick Middleton | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 280[1] | 900 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

11 Métis & Dakota dead[1][2] 18 wounded[1] |

10 dead[3] 40 wounded[3] | ||||||

| Official name | Battle of Tourond's Coulee / Fish Creek National Historic Site of Canada | ||||||

| Designated | 1923 | ||||||

The Métis conflict area is circled in black.

The Battle of Fish Creek (also known as the Battle of Tourond's Coulée ),[4] fought April 24, 1885 at Fish Creek, Saskatchewan, was a major Métis victory over the Canadian forces attempting to quell Louis Riel's North-West Rebellion. Although the reversal was not decisive enough to alter the ultimate outcome of the conflict, it was convincing enough to persuade Major General Frederick Middleton to temporarily halt his advance on Batoche, where the Métis would later make their final stand.

The battle has been described as a military disaster for the Canadians.[5]

Battle

Middleton, having led his considerable Field Force out from Qu'Appelle on April 10, was advancing upstream from Clarke's Crossing along the South Saskatchewan River when he discovered a hastily organized ambush by Gabriel Dumont's Métis / Dakota force.

On April 23, as the militia began advancing from Clarke’s Crossing, Dumont took 200 men and rode out from Batoche toward Tourond’s Coulée. Louis Riel accompanied them. When a (false) report arrived that the North-West Mounted Police were advancing on Batoche, Riel returned there with 50 men. Dumont stationed most of his men in the coulée, where they set to work digging rifle pits. The militia would cross the coulée the next day, and it was then that the concealed men in the rifle pits would ambush them. Dumont took a smaller party of twenty horsemen forward of the coulée. Their task was to seal the exit when the ambush was sprung. “I want to treat them like buffaloes,” Dumont said of Middleton’s men.[6]

Dumont and his twenty men hid in a poplar bluff. There were not yet any leaves, however. On the morning of April 24, before the infantry could cross the coulée, a Canadian cavalryman of Boulton’s Scouts spotted the Métis horsemen. Dumont’s Métis and Boulton’s force then opened fire on each other. The Scouts dismounted and began firing into the coulée, and the main body of Canadian infantry advanced to the coulée’s edge.[7]

The Métis pounded Middleton’s men with one devastating fusillade before withdrawing into cover and restricting themselves to sniper fire in order to conserve ammunition.

With half of his force on the opposite side of the river, Middleton was unable to bring his full numerical superiority to bear. One of his artillery batteries opened fire on the Métis to little effect, although well-fired cannonades did succeed in driving away Dumont’s Cree allies before their weight could be added to the battle.

Strung out along the coulée’s edge, silhouetted against the sky, the militia fired a vast amount of ammunition at their enemies, succeeding mostly in showering tree branches across the ravine, but when the artillerymen pushed their guns to the coulée’s edge to try to fire down at the concealed enemy, they suffered heavy casualties.[8] The only targets the militia could clearly see were the enemy’s tethered horses. They slaughtered about fifty of these.[9]

General Middleton behaved with reckless bravery, placing himself in full view of the enemy. A bullet tore through his fur hat, and his two aides-de-camp were both wounded by his side. The frustrated Canadians, their casualties mounting, undertook several fruitless rushes into the ravine. A few infantry regulars under Middleton’s command made one charge. Another, larger one was carried out by the Royal Winnipeg Rifles militia. This latter advance was parried by Métis use of improvised barricades within the coulée.[10] These uncoordinated advances accomplished nothing but more Canadian casualties.

Despite the heavy casualties inflicted upon the enemy, Métis morale deteriorated as the battle wore on. Famished, dehydrated, and low on ammunition (conditions that had plagued them throughout the rebellion), Dumont's rebels, though relatively impervious to enemy fire from within their gullies and ravines, knew that their positions would not hold in the face of any sustained enemy assault.

However, Middleton, distressed by the casualties he was taking, erred on the side of caution and opted for retreat. Weeks later, after news reached him of the Cree victory over Colonel Otter – to whom had been issued the dreaded Gatling gun – at Cut Knife, Middleton embarked once more on decisive action against Batoche.

Maps

- Military Battlefield Map of Fish Creek

- Military Map of Fish Creek view 1

- Military Map of Fish Creek view 2

- Military Map of Fish Creek Rifle Pits

Legacy

National Historic Sites and Monuments Board[11]

The site of the battle was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1923.[12]

In the spring of 2008, Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport Minister Christine Tell proclaimed in Duck Lake, that "the 125th commemoration, in 2010, of the 1885 Northwest Resistance is an excellent opportunity to tell the story of the prairie Métis and First Nations peoples' struggle with Government forces and how it has shaped Canada today."[13]

The Battle of Fish Creek National Historic Site, now named Tourond's Coulée / Fish Creek National Historic Site, preserves the battlefield of April 24, 1885 at la coulée des Tourond , and the story of Madame Tourond’s home. The National Historic site of Middleton’s camp and graveyard is across the Fish Creek water body and is north west of the theatre of battle which occurred in the creek valley west of the Tourond farmhouse site.[14]

References

- 1 2 3 Panet, Charles Eugène (1886), Report upon the suppression of the rebellion in the North-West Territories and matters in connection therewith, in 1885: Presented to Parliament.(p.20), Ottawa: Department of Militia and Defence

- ↑ "Heroes of the 1885 Northwest Resistance. Summary of those Killed.". Barkwell, Lawrence J. Louis Riel Institute. 2010. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- 1 2 Panet, Charles Eugène (1886), Report upon the suppression of the rebellion in the North-West Territories and matters in connection therewith, in 1885: Presented to Parliament., Ottawa: Department of Militia and Defence

- ↑ Parks Canada (2007-11-17), Famous 1885 Battle Site Gains New Name, Ottawa: Government of Canada, archived from the original on 2009-08-05

- ↑ "Battle of Fish Creek".

- ↑ Morton, Desmond, The Last War Drum, Hakkert, Toronto, 1972, (Canadian War Museum Historical Publications Number 5), p.62.

- ↑ Beal, Bob, and Macleod, Rod, Prairie Fire, McClelland and Stewart, Toronto, 1994, p.230.

- ↑ Beal and Macleod, pp.230-231.

- ↑ Morton, pp.64-65.

- ↑ Mulvany, Charles Pelham, The History of the North-West Rebellion of 1885, Toronto, Hovey & Co., 1886, pp.131-132 and 141.

- ↑ "Fish Creek The Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture". Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied Research. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ Battle of Tourond's Coulee / Fish Creek. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ "Tourism agencies to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the Northwest Resistance/Rebellion". Home/About Government/News Releases/June 2008. Government of Saskatchewan. June 7, 2008. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ "Battle of Fish Creek" (ashx). National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada. 2007. Retrieved 2009-09-20. html